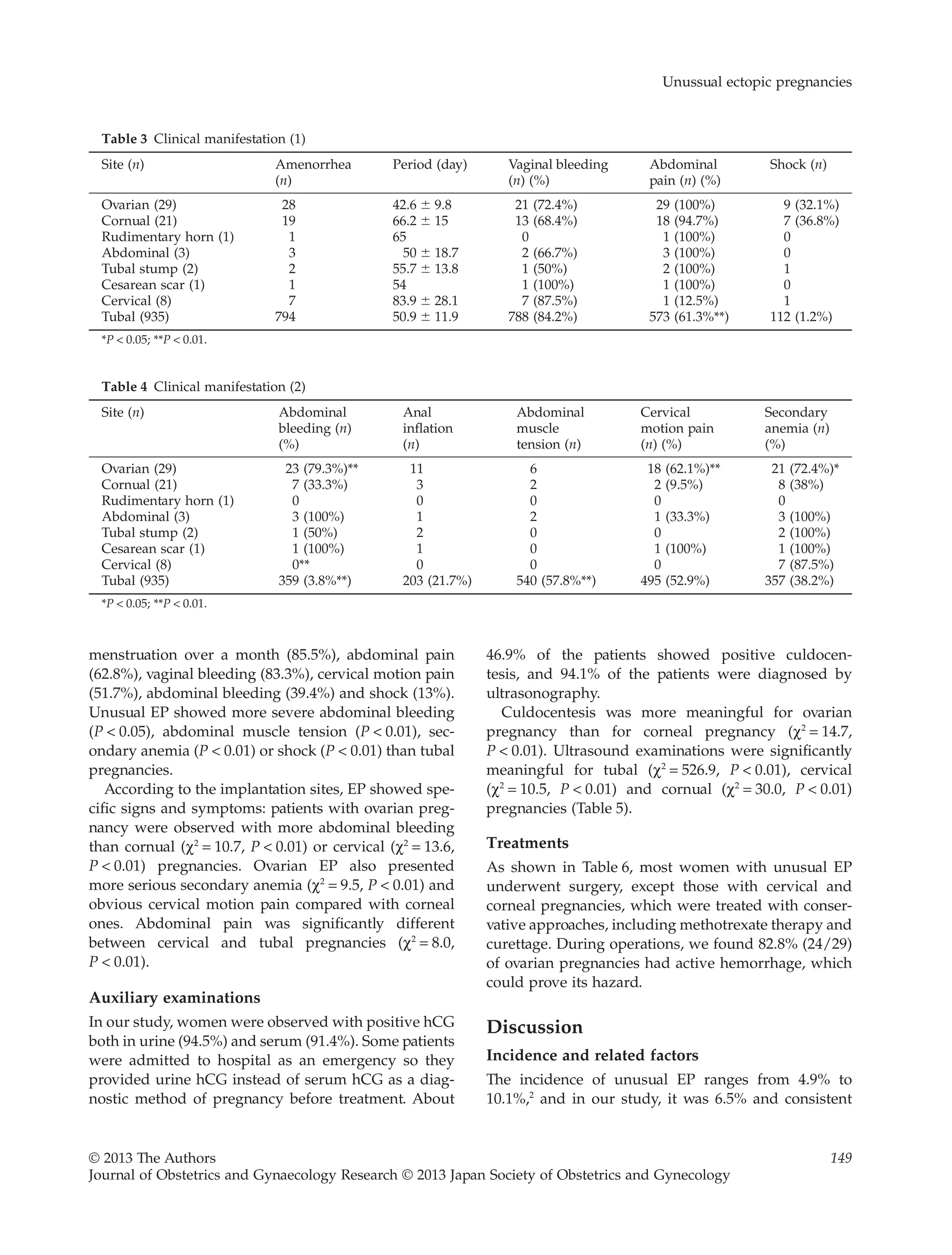

This study retrospectively analyzed 65 cases of unusual ectopic pregnancies out of 1000 total ectopic pregnancy cases over a 10-year period. The study found that ovarian pregnancies were associated with intrauterine device placement and pelvic inflammatory diseases. Extratubal ectopic pregnancies like those in the ovaries, cervix, and abdomen presented more serious symptoms and had higher misdiagnosis rates than tubal pregnancies. Most unusual ectopic pregnancies required surgery for treatment, though some early cervical and corneal pregnancies were treated with conservative methods like mifepristone and methotrexate or curettage.

![with the reports. Although this incidence is low, the

danger and mobility from an extratubal pregnancy is

higher than normal pregnancy. Moreover, the success

rate for a subsequent pregnancy will be reduced after

EP.

In our series, the most common site of implantation

in EP is the tube, followed by the ovary, corn, cervix

and abdomen. The rarest site is the cesarean scar.

Ovarian pregnancy is very rare, accounting for 0.3%–

3.0% of EP,3

and its incidence in our investigation was

3.1%. Ovarian pregnancy is generally believed to be

associated with pelvic inflammatory diseases and pre-

vious surgery in the pelvic cavity. We found 44.8% of

the cases (13/29) had a history of pelvic inflammatory

diseases, and 55.2% (16/29) had a history of delivery or

curettage. Patients with a history of pelvic inflamma-

tory diseases showed a significant difference in ovarian

than corneal and tubal pregnancies. Furthermore, even

without inflammatory history, pelvic surgeries may

also cause ovarian inflammation and thicken the albug-

inea, which could lead to a relative lack of follicular

fluid pressure. Finally, it would generate ovulation dis-

order. Ovum might be detained in the broken follicles

and fertilized just in the ovary.

Reportedly, the use of IUD seems to be dispropor-

tionately associated with ovarian pregnancy.4,5

In our

series, 10 out of 29 patients had a history of IUD place-

ment (27.6%), which indicated statistical relevance

between IUD and ovarian pregnancy, and suggested

that IUD placement may change some manners in the

pathophysiological environment of the ovary. IUD was

hypothesized to successfully prevent all pregnancies,

except ovarian ones.6

Therefore, the history of IUD

placement is useful if a patient is suspected of ovarian

pregnancy. However, it was reported that the incidence

rate of PID among IUD users as reported from different

studies depends heavily on the definition used and the

means available for diagnosing PID. It varies from 1 per

100 to 1 per 1000 woman-years – a tenfold difference –

in different studies. PID risk has been found to be

sixfold higher in the first month after IUD insertion

than it is thereafter. Beyond the first month or so after

insertion, the incidence of PID is low among women

using IUD and at a level that appears similar to that for

women in general.7

The incidence of cervical pregnancy is less than 1%

of all EP,8,9

varying from 1/10003

to 1/18 000.4

the cause

may be associated with the following factors: (i) cesar-

ean section and usage of IUD might interfere with the

implantation of blastocyst; (ii) repeated endometrial

curettages might damage the endometrium or form a

scar, and thus retard the pass and implantation of blas-

tocyst at cervix (in our series, 75% of the cases [6/8]

reported a history of induced abortion or cesarean

section and placement of IUD, which suggested that

intrauterine surgeries could be an important cause for

cervical pregnancy); and (iii) with the development of

reproductive technology, embryo transfer as in vitro

fertilization is also a substantial cause.

Misdiagnosis rate

The misdiagnosis rate of extratubal pregnancies is

quite high (96.6%). Ovarian and tubal pregnancies are

difficult to distinguish, even by ultrasound, because

their clinical manifestations are similar. In our investi-

gation, only one case of ovarian pregnancy was diag-

nosed by ultrasound. Reportedly, all 24 cases of ovarian

pregnancies in six hospitals were preoperatively mis-

diagnosed.10

However, positive culdocentesis results

were more common in patients with ovarian pregnan-

cies than with cornual pregnancies, probably because a

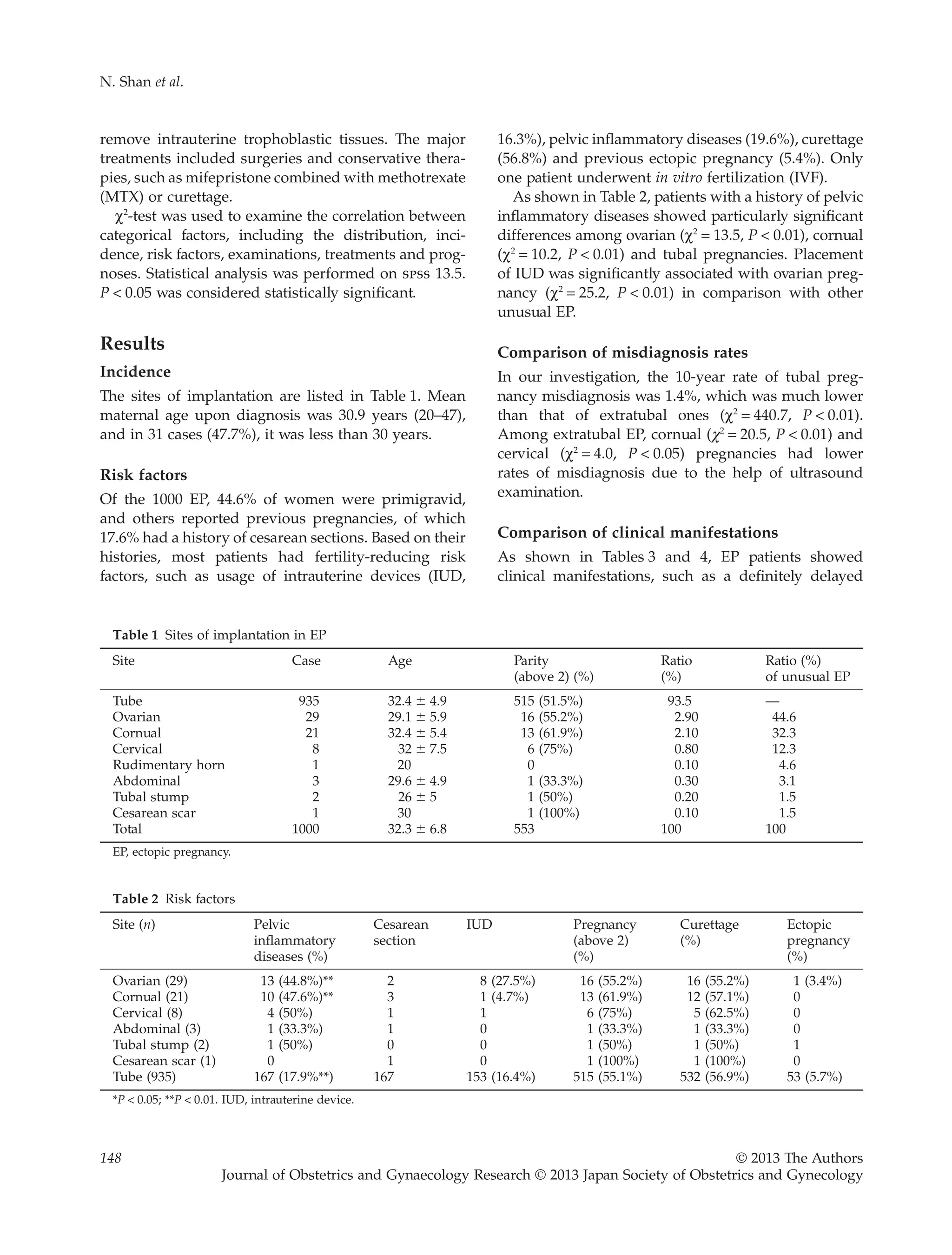

Table 5 Auxiliary examination

Site (n) Serum

hCG (n)

Urine

hCG (n)

Culdocentesis

positive

(n)

Ultrasound

Diagnosis

(n)

fetal heart

movement

Persistent

hCG

secretion

Cases of

misdiagnosis

Ovarian (29) 17 (58.6%) 25 (86.2%) 20** (69%) 1 (3.4%) 1 (3.45%) 6 (20.7%) 28 (96.6%**)

Cornual (21) 13 (61.9%) 13 (61.9%) 3 (14.3%) 12 (57.1%) 0 0 5 (23.8%**)

Cervical (8) 6 (75%) 5 (62.5%) 0 5 (62.5%) 0 0 2 (25%*)

Rudimentary horn (1) 1 (100%) 1 (100%) 0 1 (100%) 0 1 (100%) 0

Abdominal (3) 2 (66.7%) 2 (66.7%) 0 0 2 (66.7%) 0 3 (100%)

Tubal stump (2) 0 2 (100%) 1 (50%) 0 0 0 2 (100%)

Cesarean scar (1) 1 (100%) 1 (100%) 0 0 0 0 1 (100%)

Tubal (935) 874 (93.5%) 896 (95.8%) 445 (47.6%) 922 (98.6%) 38 (4.06%) 0 13 (1.4%**)

Total 914 (91.4%) 945 (94.5%) 46.9 (46.9%) 941 (94.1%) 41 (4.1%) 7 (0.7%) 54 (5.4%)

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. hCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin.

N. Shan et al.

150 © 2013 The Authors

Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research © 2013 Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unusualectopicpregnancies-140317061353-phpapp02/75/Unusual-ectopic-pregnancies-4-2048.jpg)

![implanted in the cervical canal, the higher capacity it

has to grow and hemorrhage. Some diagnostic criteria

for cervical pregnancy are:

1 Clinical signs and symptoms: recurring vaginal

bleeding without pain was observed during early

gestation, often followed by uncontrolled hemor-

rhage. In our investigation, 87.5% (7/8) of cases were

observed with vaginal bleeding, involving three

cases of emergency.

2 Gynecological examination: cervix is dilated; cervical

canal increasingly thickens like barrel. Doctors could

see or even touch placenta in cervix. Two cases pre-

sented cervical dilation and another two cases

showed a flabby cervix. The examination may cause

severe hemorrhage, so it should be deliberated

before examination.

3 Serum b-hCG assessment and ultrasound examina-

tion. Quantitative serum hCG in cervical pregnancy

is often present below the normal pregnancy due to

poor blood supply. Compared with other unusual

EP, cervical pregnancy showed atypical abdominal

pain or bleeding. This may be the result of early

admission.

In abdominal pregnancy, with either tubal abortion or

intraperitoneal rupture, the entire conceptus may

be extruded from the tube. If an early conceptus is

expelled essentially undamaged into the peritoneal

cavity, its placental attachment may persist, or it may be

reimplanted almost anywhere and grow as an abdomi-

nal pregnancy. This is unusual, and most small concep-

tuses can be reabsorbed. They may occasionally remain

in the cul-de-sac for years as an encapsulated mass, or

even become calcified to form a lithopedion.11

All our cases are secondary. The first one occurred

due to rupture of tubal pregnancy, and then the con-

ceptus developed on the posterior wall of bladder. The

second one was from rupture of rudimentary horn

pregnancy and the conceptus grew in Douglas’ space

on the ligament of the right iliac fossa. The last one

happened due to tubal interstitial pregnancy and the

conceptus dropped into the abdominal cavity. During

the operation, the fetus was found alive in the abdomi-

nal cavity surrounded by blood. The placenta was

attached to the greater omentum.

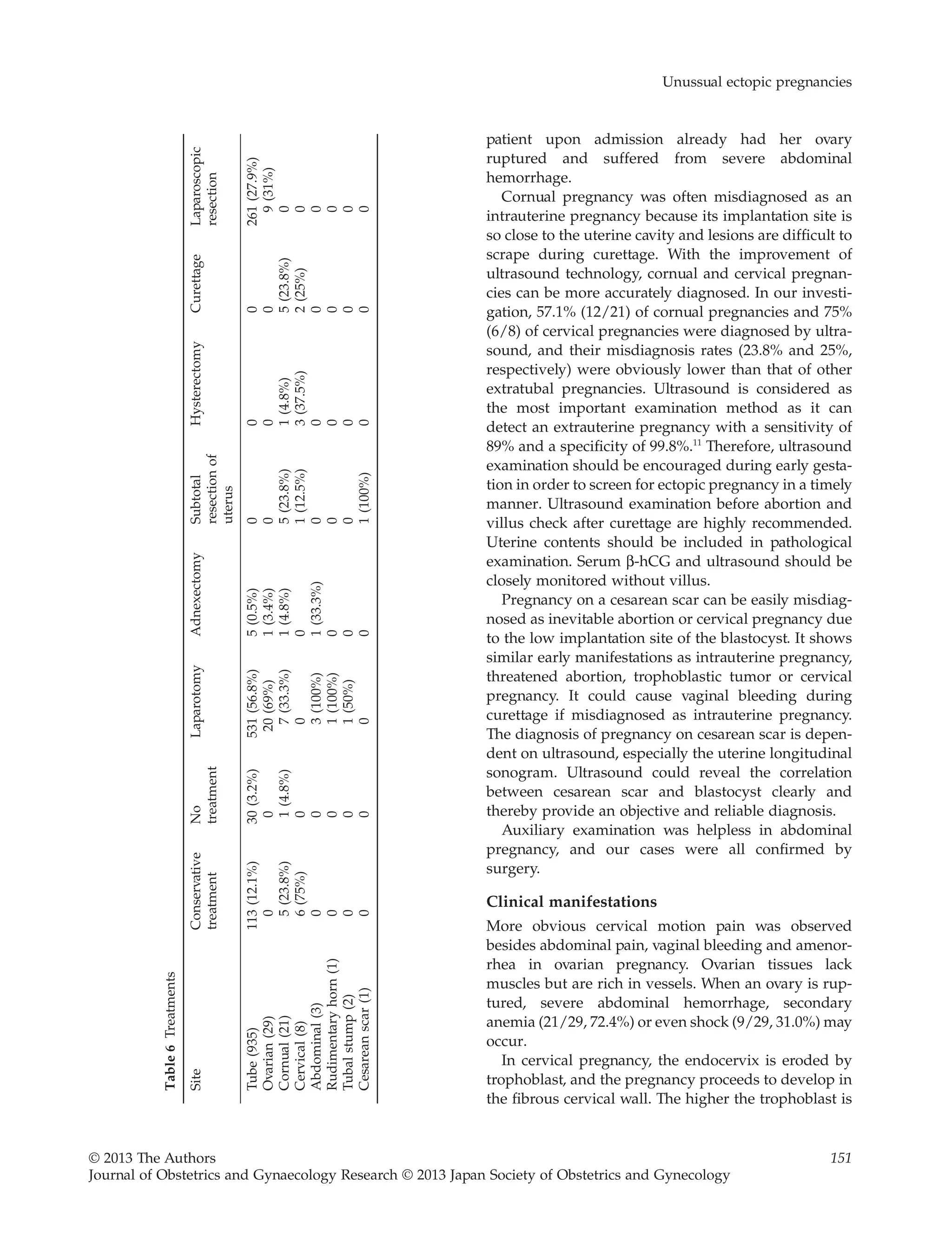

Treatment and prognosis

Twenty-eight out of 29 women with ovarian preg-

nancies underwent surgery by resection of the ovarian

wedge or partial oophorectomy. Most reports advocate

preserving ovarian tissues as much as possible.

Doctors cut off the affected annex only under serious

damages.

In the past, it was suggested to cut off the uterine

corpus to avoid rupture of cornual pregnancy, and

hysterectomy was recommended if necessary. In our

study, seven cases (33.3%) underwent lesion resection

on corpus; and five cases (23.8%) received sub-

total hysterectomy due to ruptures. In recent years,

many successful cases of conservative treatment were

reported. We treated five patients with conservative

therapies, including mifepristone, curettage and

MTX, which achieved excellent results. However,

some reports also pointed out that conservative treat-

ment for patients in this type of pregnancy with long-

time amenorrhea and abdominal pain may not

succeed easily.

Before 12 weeks’ gestation, invasion of trophoblastic

cells in the cervical wall is not deep enough, so conser-

vative treatments for cervical pregnancy can be suc-

cessful.12

Treatments include: (i) hysterectomy and

subtotal hysterectomy (they are operated only after

failure of conservative treatments or uncontrolled hem-

orrhage [they were used in three cases]); and (ii) con-

servative treatments (the key was early diagnosis and

treatment). Recently, the use of curettage and hysterec-

tomy has been reduced gradually. They are only used

as alternative therapies for MTX and uterine artery

embolization. Reportedly, MTX can be used by sys-

temic or local injection. It could reach a high effect of

80%.13

Usage of both mifepristone and MTX was better

than single MTX for cervical pregnancy, as the former

showed a high success rate and lower toxicity.14

This

method could enhance the toxicity to trophoblast cells

and kill the embryo effectively.

In our investigation, four cases of conservative treat-

ments and two cases of curettage were successful.

However, vaginal bleeding may still occur after con-

servative treatments. Doctors should closely monitor

patients’ conditions. One patient underwent hysterec-

tomy after conservative treatment due to recurring

vaginal bleeding.

Rudimentary horn in the uterus is the result of devel-

opmental defects on lower segment in the duct of

Muller, which caused unequal formation on both sides.

A small appendage formed next to the normal uterus

and connected it through a bunch of fibrous tissues.15

Compared with the normal uterus, the rudimentary

uterus has thicker muscles (most hypoplasia) with

dense vessels. Thus, severe hemorrhage often occurs

after the rupture of pregnancy.

N. Shan et al.

152 © 2013 The Authors

Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research © 2013 Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unusualectopicpregnancies-140317061353-phpapp02/75/Unusual-ectopic-pregnancies-6-2048.jpg)