The study of gender equality in Italian universities reveals a history of ambition and ongoing challenges.

In Italy, universities must adopt both a gender equality plan (GEP) and a gender equality budget in order to receive funding from the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) - a requirement that aligns national priorities with European standards.

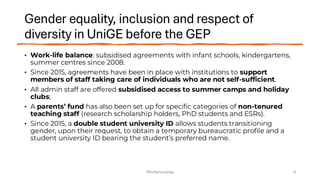

At the University of Genoa, equality and inclusion have been part of the campus culture long before formal GEPs existed.

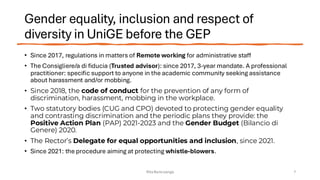

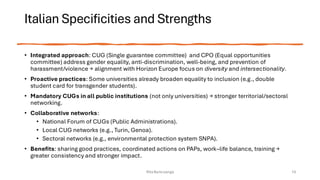

Staff and students benefit from supportive policies such as subsidised childcare, summer camps, support funds for parents and even a dual student card for transgender students. Telecommuting policies, anti-harassment codes of conduct, and special offices such as the Committee on Uniformity Guarantee (CUG) and the Committee on Equal Opportunity (CPO) demonstrate a commitment to a fair and safe academic environment. These bodies, together with the Vice-Chancellor’s Equal Opportunities Officer, oversee the positive action plans and budget for equality issues and ensure that initiatives are strategic and effective.

However, progress is not without its hurdles. Gender equality initiatives are often at the interface between general structural objectives and specific positive action measures. While targeted measures can bring about change, they alone cannot change entrenched norms and practices. Evidence from Italy and international programmes such as Athena Swan highlights a persistent problem: The extra work required to implement GEPs often comes at the expense of women, who receive little professional recognition despite their contribution. While work-life balance programmes are important, they are not enough to drive the systemic change needed for true equality.

Italy’s strengths lie in its co-operative and integrated approach. Mandatory CUGs in all public institutions create strong local and sectoral networks that enable universities to share best practice, coordinate training, and harmonise Positive Action Plans.

International networks that have emerged from EU projects provide further inspiration, although customisation to local circumstances, such as national recruitment regulations, is crucial.

Innovative measures such as support for students undergoing gender transition show how Italian universities are driving inclusion beyond formal compliance.

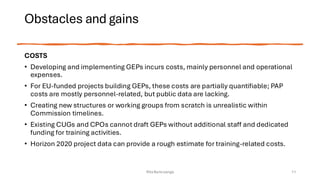

The way forward remains complex. Implementing GEPs requires resources, staff and careful planning.

Training on unconscious bias needs to be tailored to the academic context, and workload distribution needs to be monitored to avoid inequality.

The Italian experience may offer a compelling template: the combination of structured planning, proactive engagement, and networked collaboration can transform policy into meaningful, sustainable change.