The Cycle Of Erosion In Different Climates Reprint 2020 Pierre Birot C Ian Jackson Keith M Clayton

The Cycle Of Erosion In Different Climates Reprint 2020 Pierre Birot C Ian Jackson Keith M Clayton

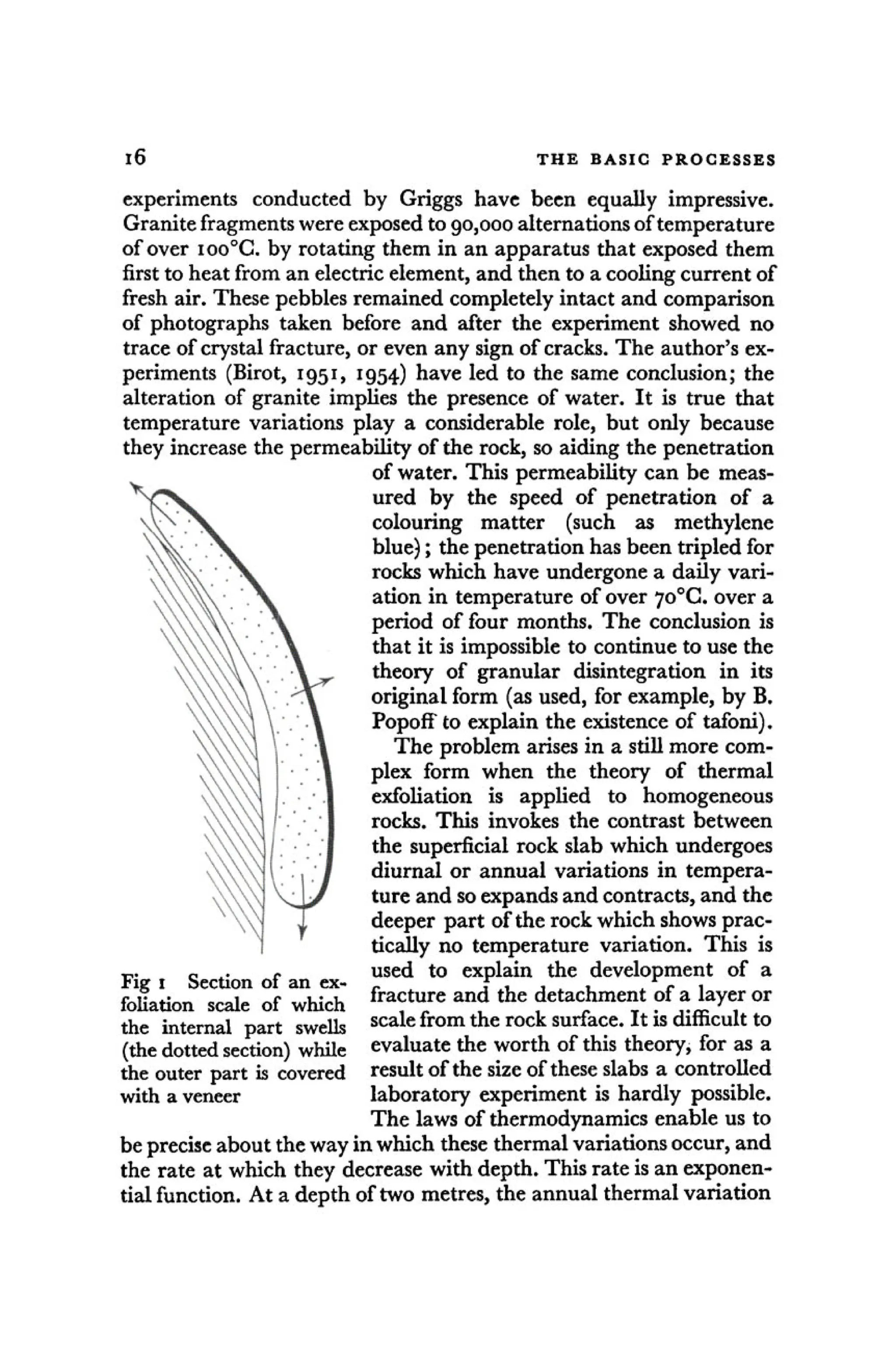

The Cycle Of Erosion In Different Climates Reprint 2020 Pierre Birot C Ian Jackson Keith M Clayton