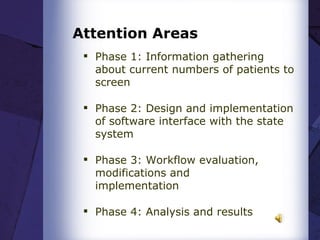

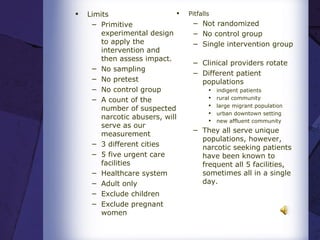

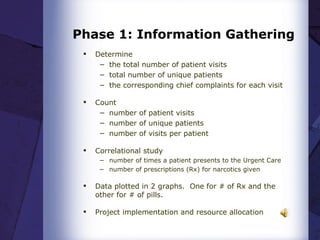

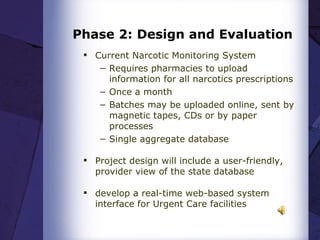

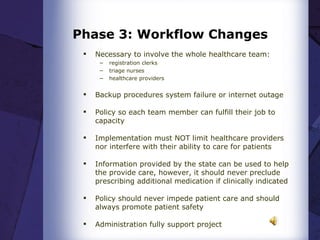

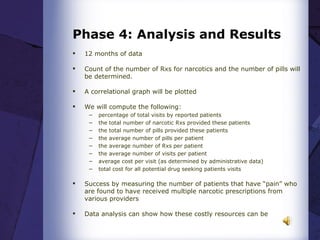

The document outlines a statewide initiative aimed at screening patients seeking narcotics in urgent care facilities to reduce prescription drug abuse. It describes a multi-phase project involving data gathering, software interface design, workflow evaluation, and analysis to identify potential narcotic abusers. The goal is to improve patient care, optimize healthcare resources, and support providers by allowing access to a state narcotics monitoring program.