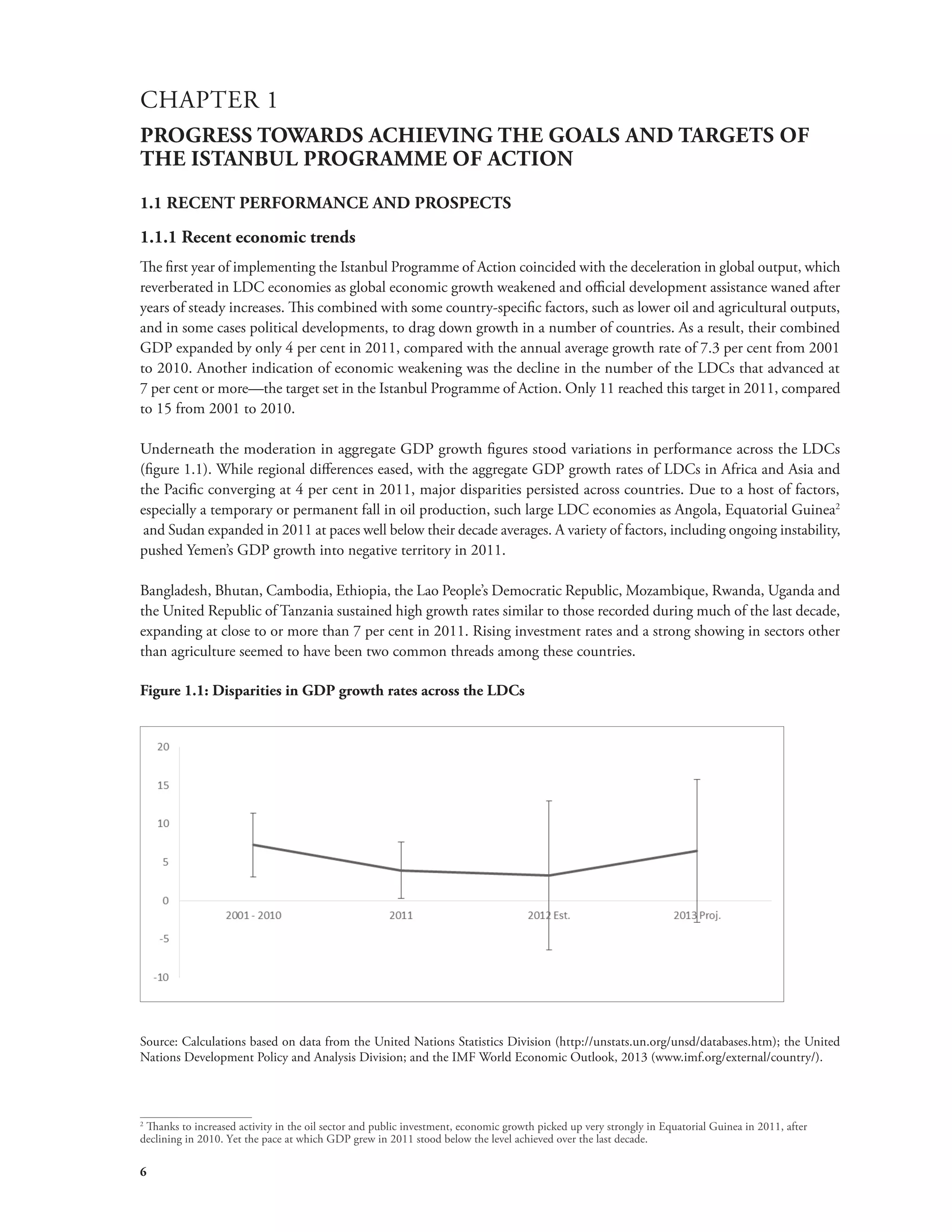

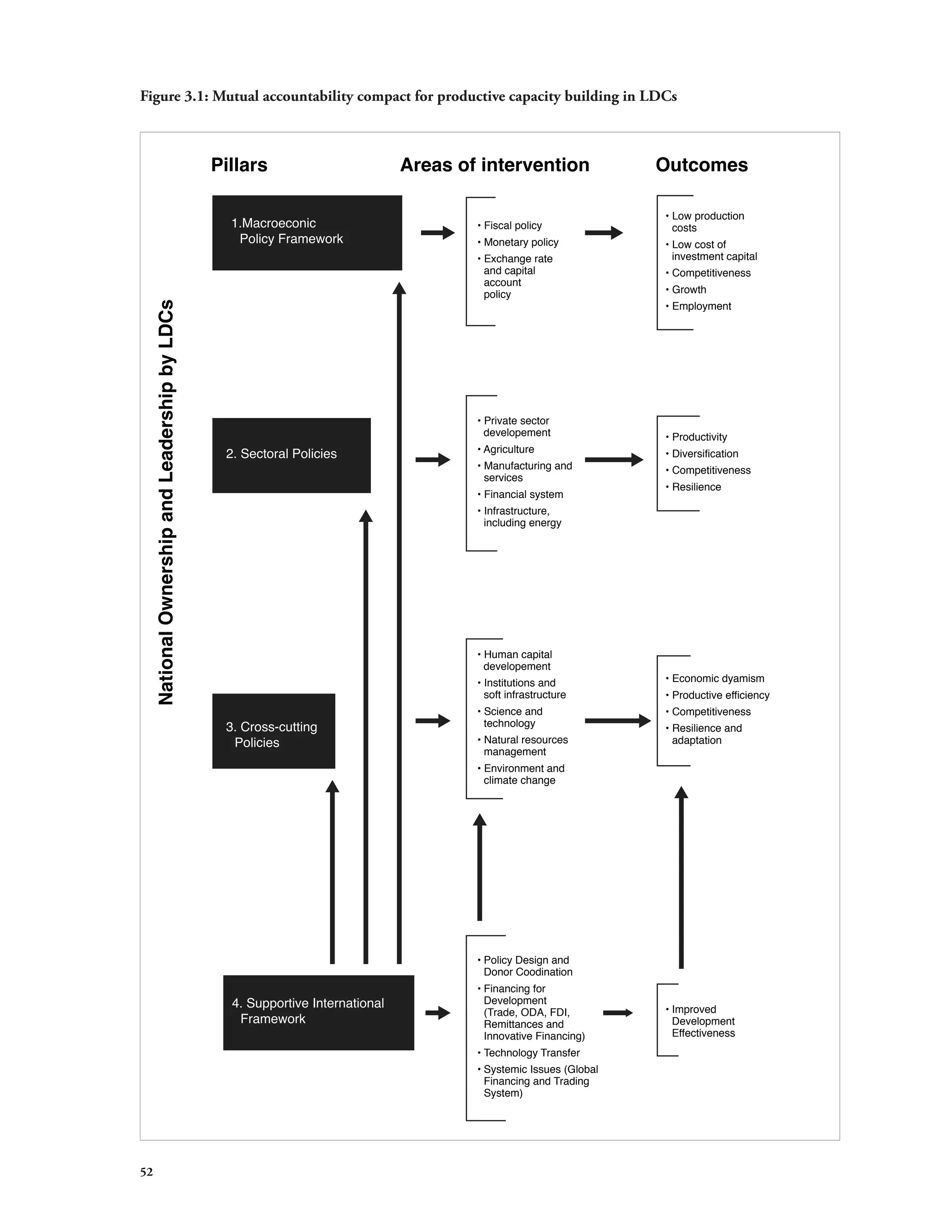

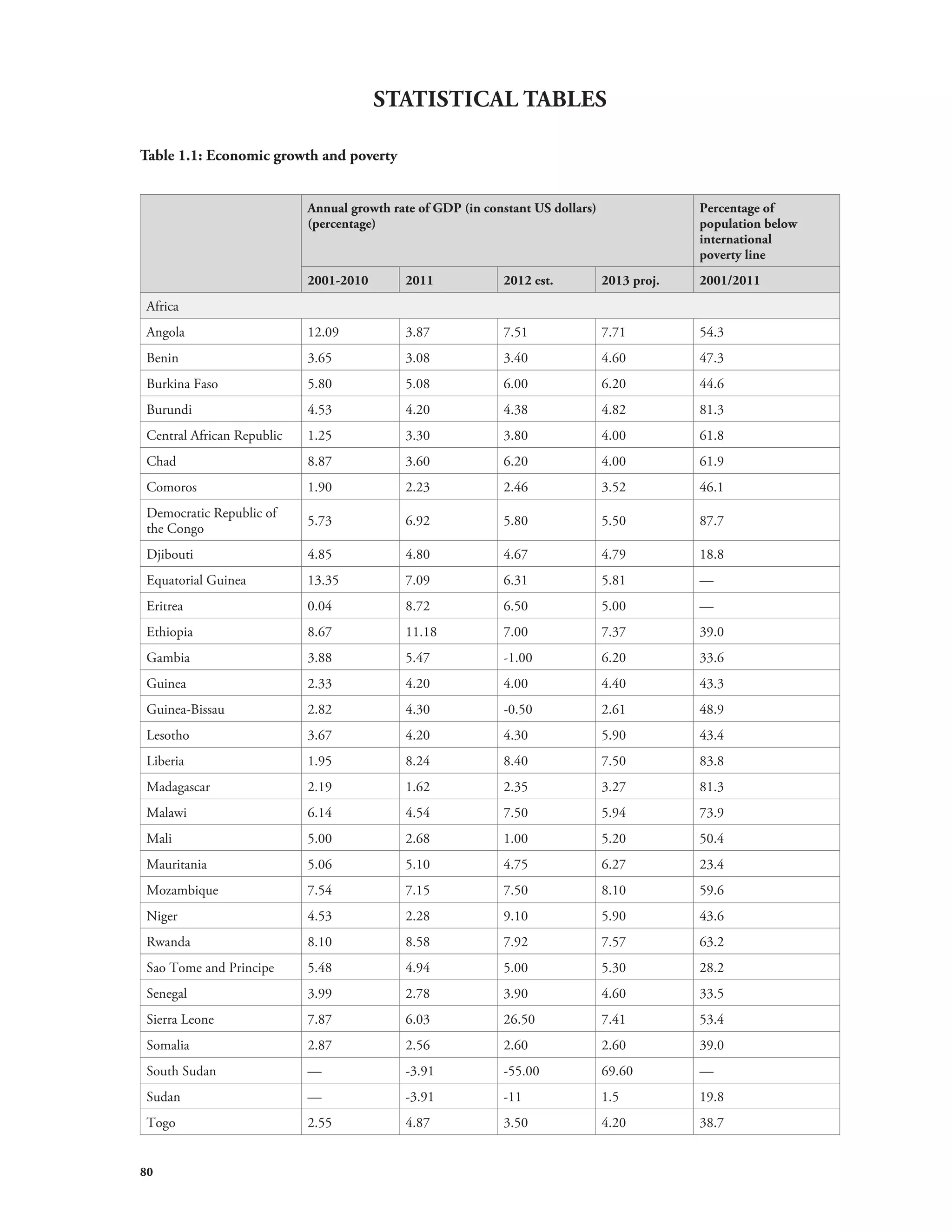

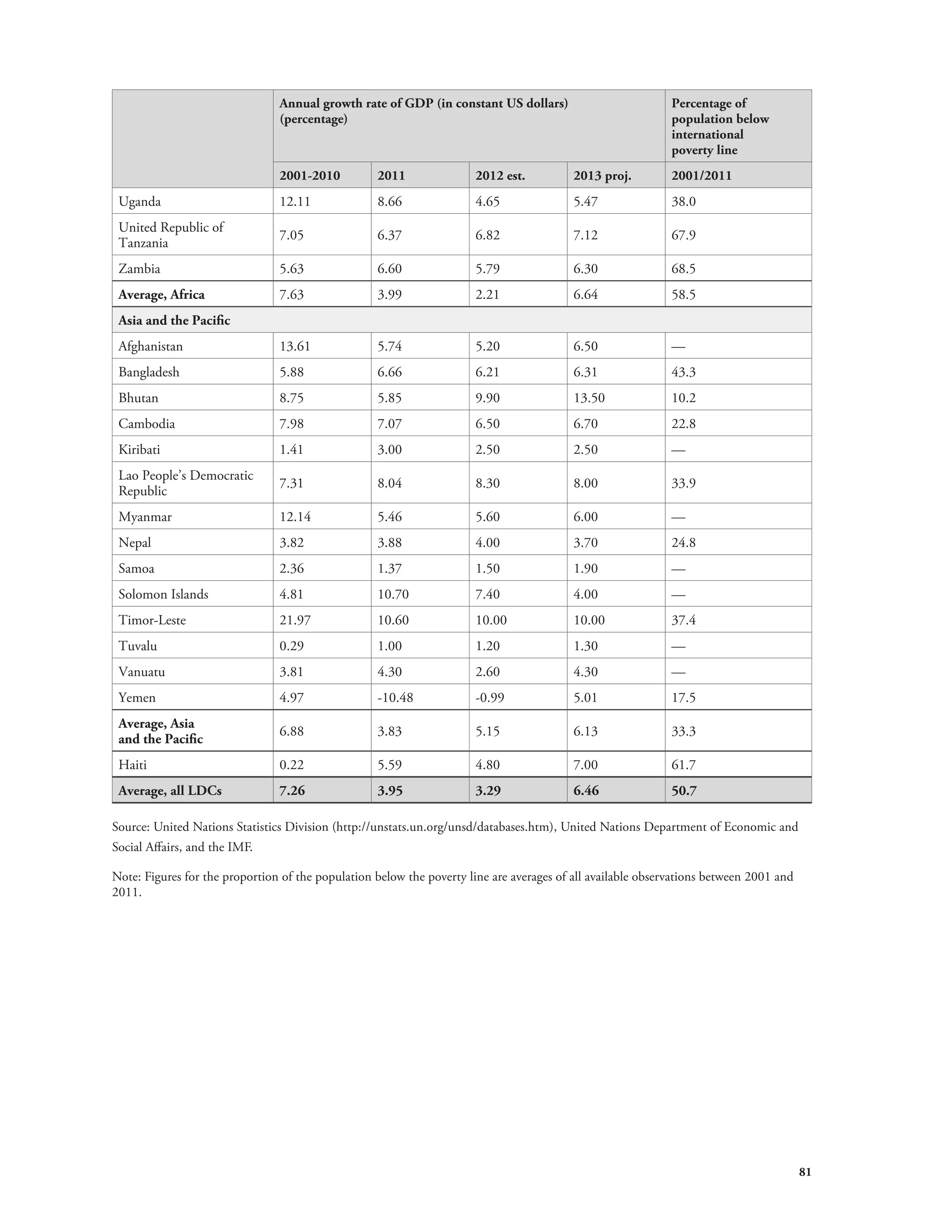

This document provides an executive summary of the 2013 State of the Least Developed Countries report. It finds that while some LDCs have experienced economic growth above 7% per year, most LDCs still face challenges such as poverty, lack of infrastructure, and limited capacity for innovation. It recognizes productive capacity building as essential for structural transformation and sustainable growth in LDCs. The report proposes a strategy for the post-2015 period focused on making employment creation the goal of macroeconomic policies and increasing the labor intensity of growth. This would require shifting to a framework targeting real development objectives through expanded policy tools.

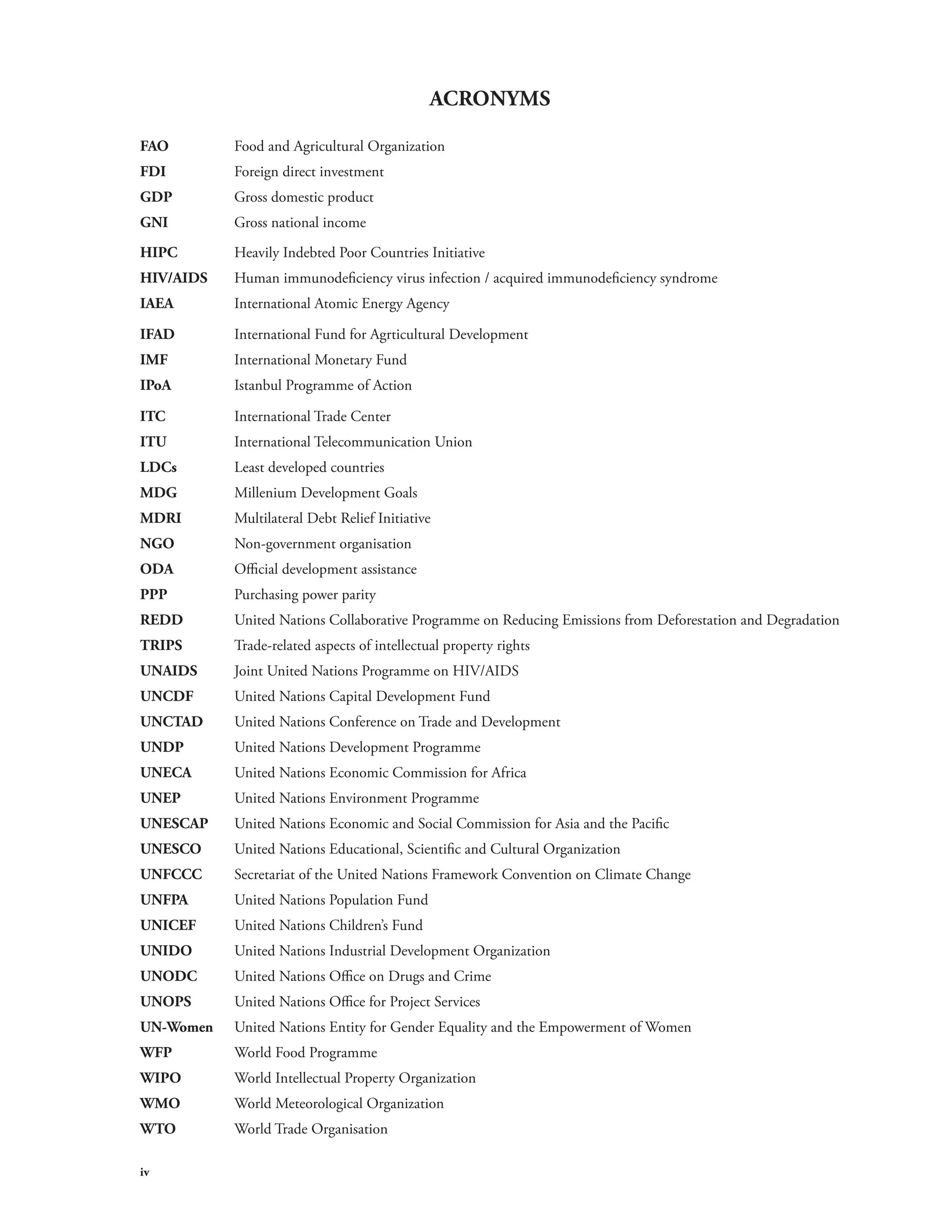

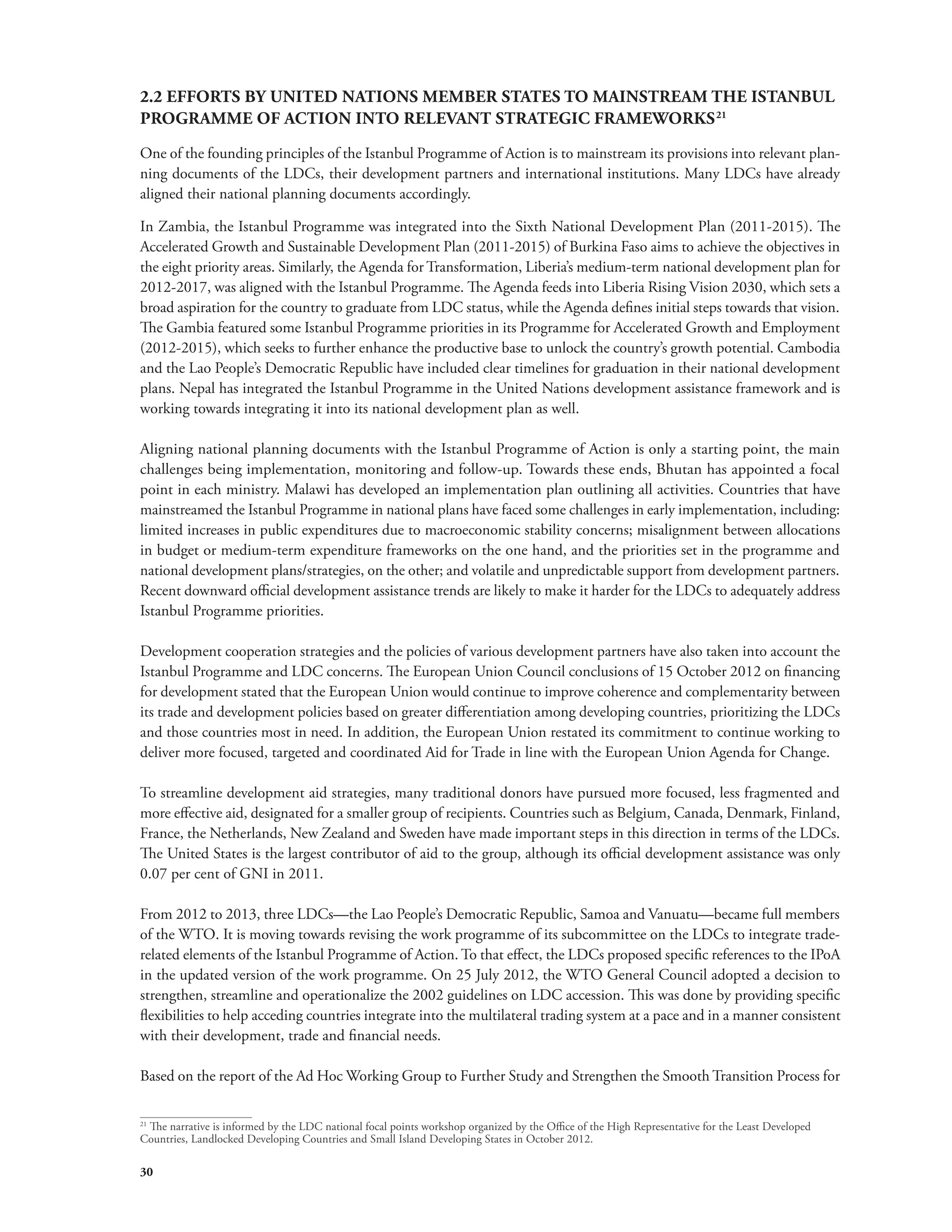

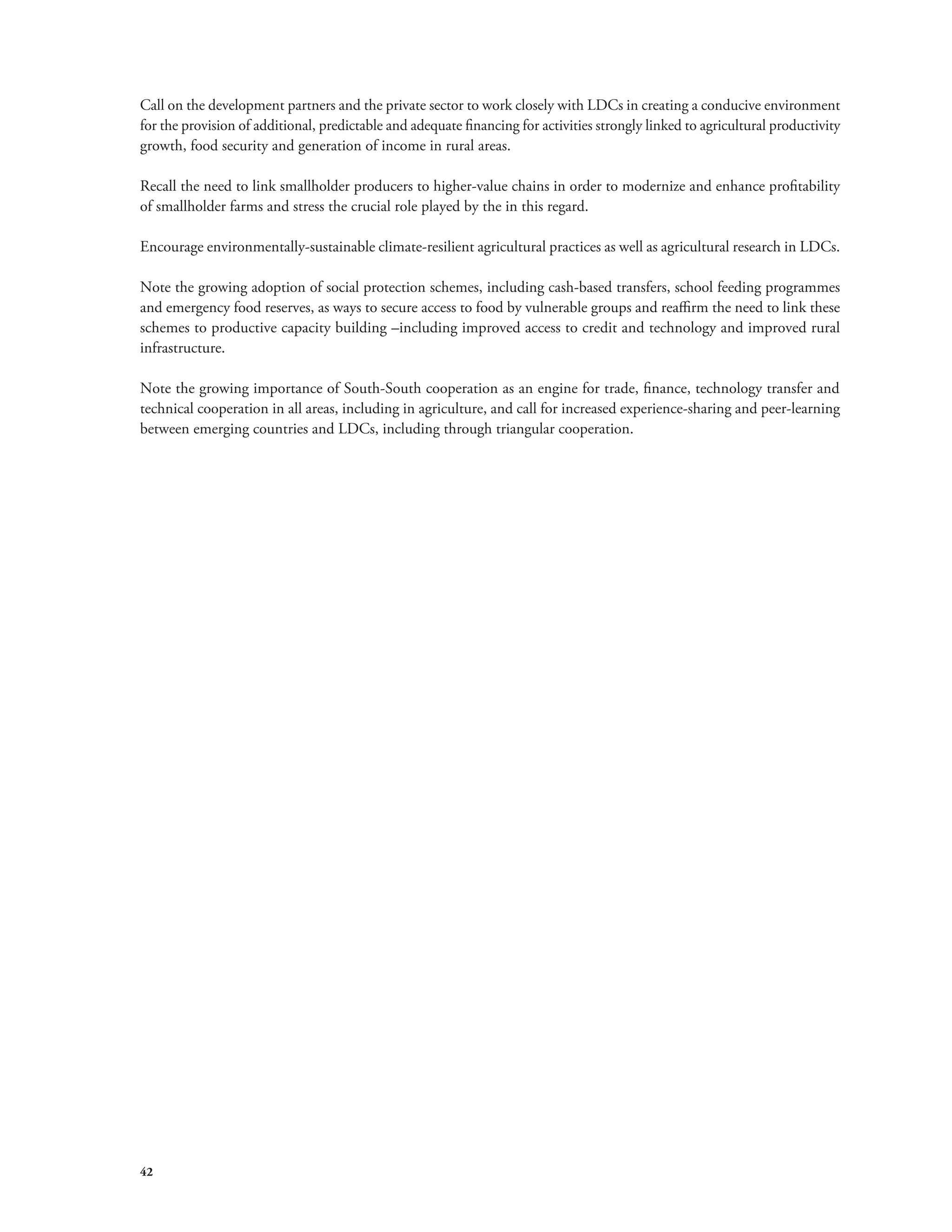

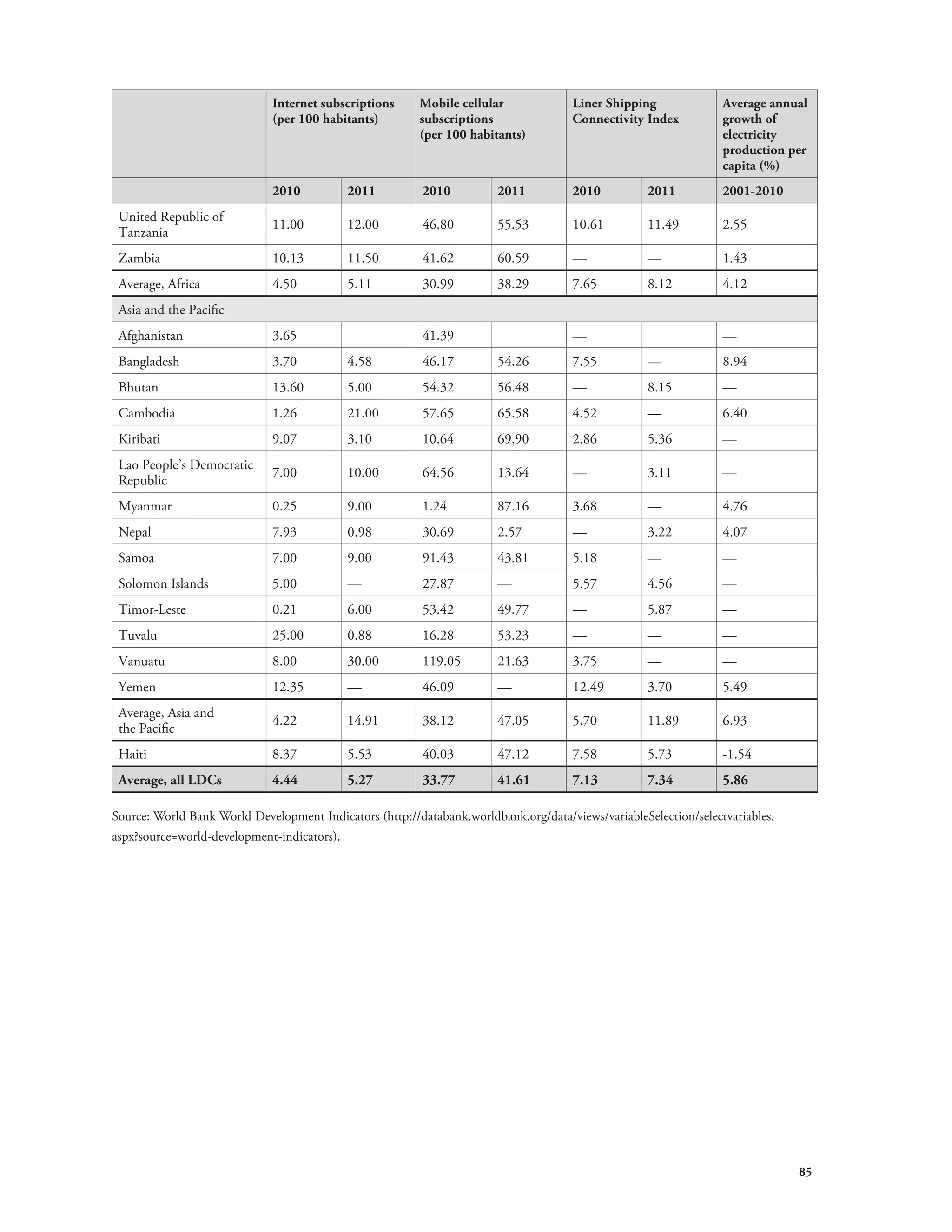

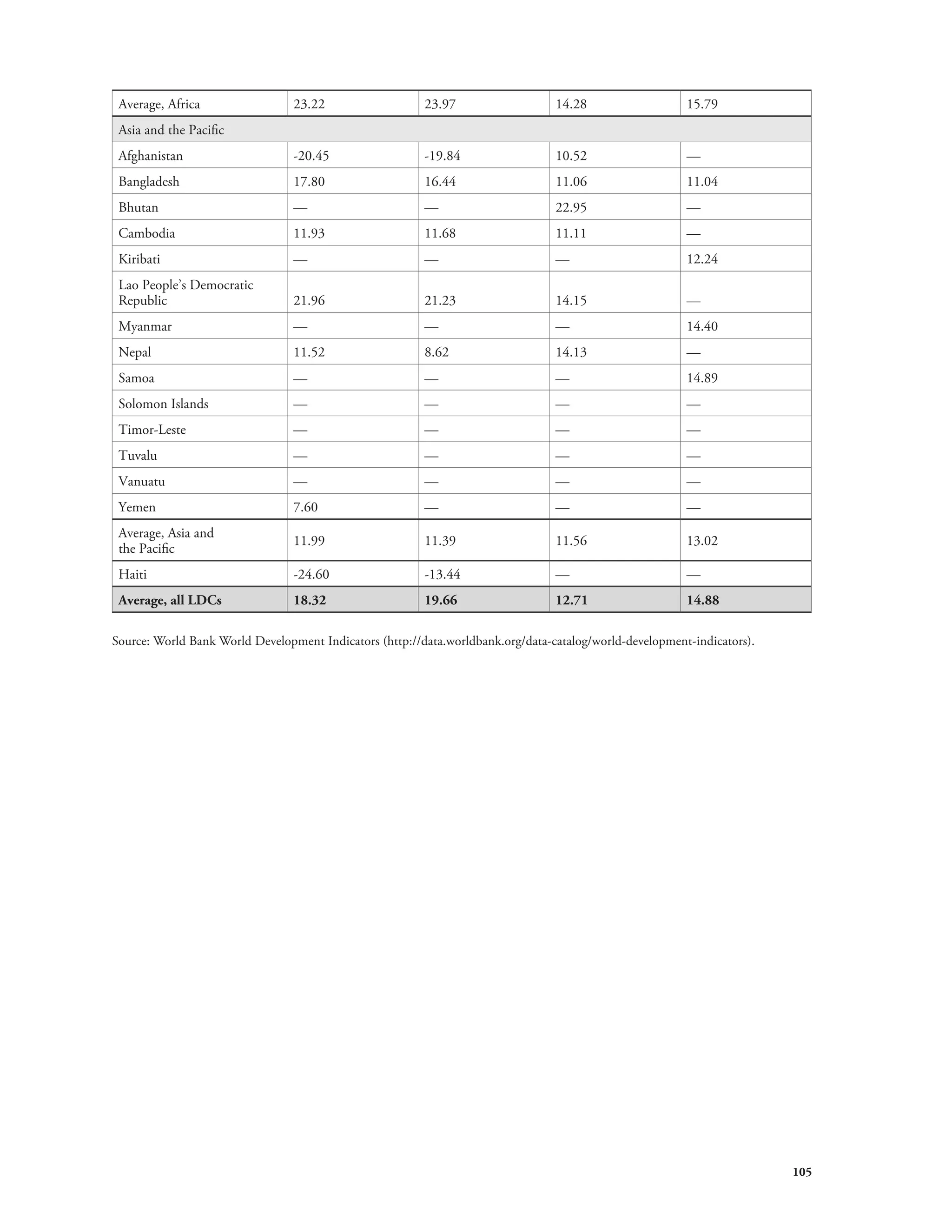

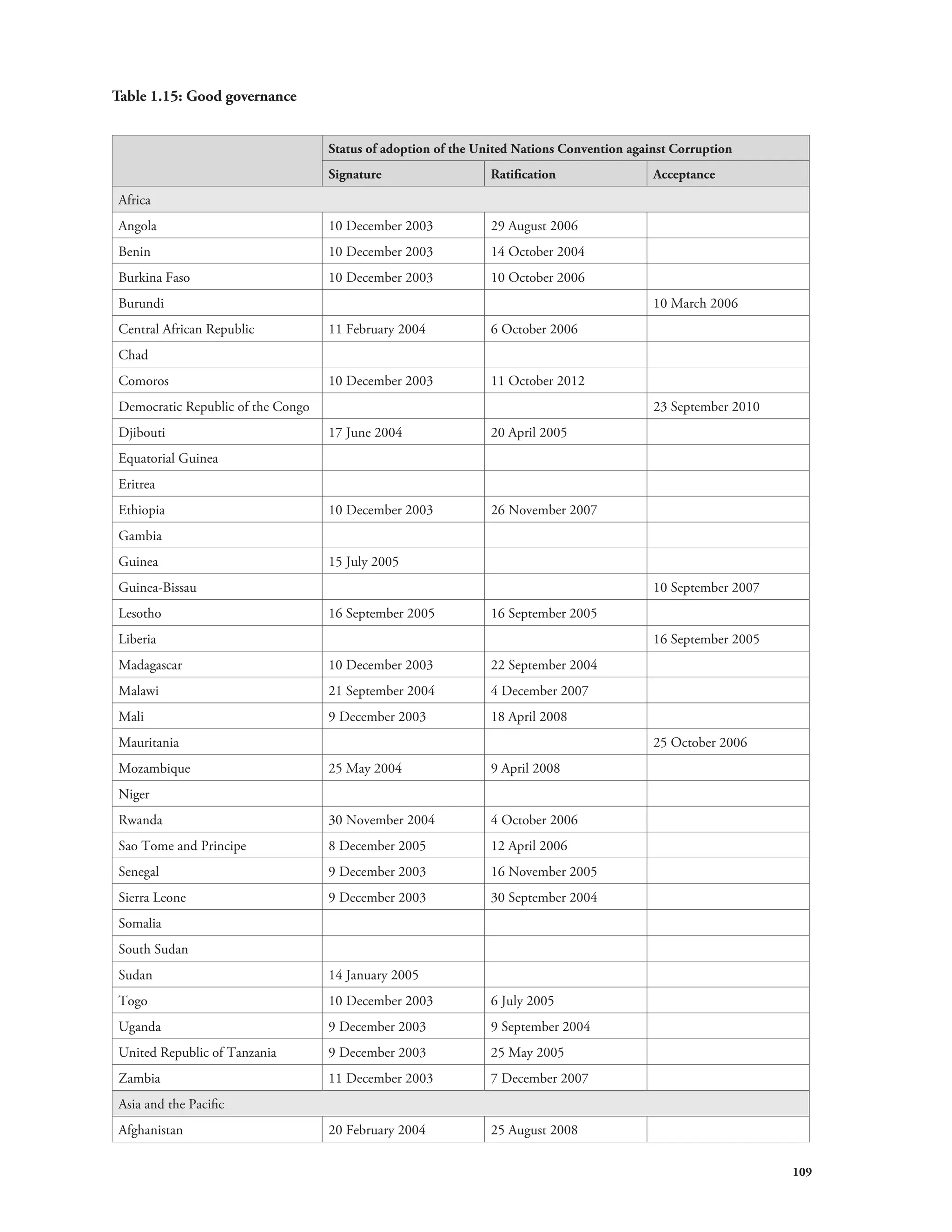

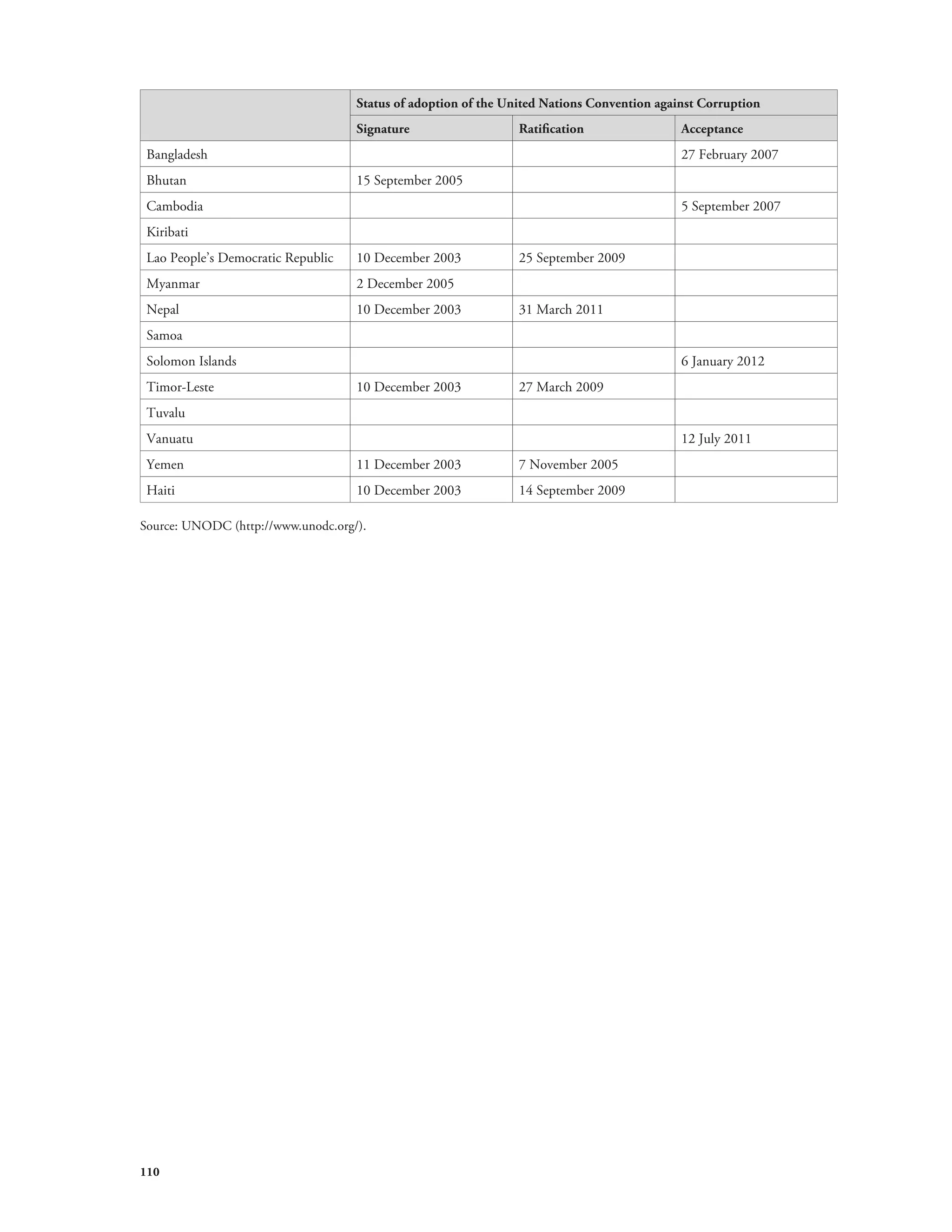

![THE 49 LEAST

DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

UN-OHRLLS

Floor 32

New York, NY 10017, USA

Tel: (917) 367-6006

Fax: (917) 367-3415

E-mail: OHRLLS-UNHQ@un.org

WWW.UN.ORG/OHRLLS

Copyright © United Nations 2013

ASIA [ 14 ]

Afghanistan

Bangladesh

Bhutan

Cambodia

Kiribati

Lao People’s

Democratic Republic

Myanmar

Nepal

Samoa

Solomon Islands

Timor-Leste

Tuvalu

Vanuatu

Yemen

LATIN AMERICA AND

THE CARIBBEAN [ 1 ]

Haiti

AFRICA [ 34 ]

Angola

Benin

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Central African Republic

Chad

Comoros

Democratic Republic

of the Congo

Djibouti

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gambia

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Lesotho

Liberia

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mozambique

Niger

Rwanda

São Tomé and Príncipe

Senegal

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Sudan

Sudan

Togo

Uganda

United Republic

of Tanzania

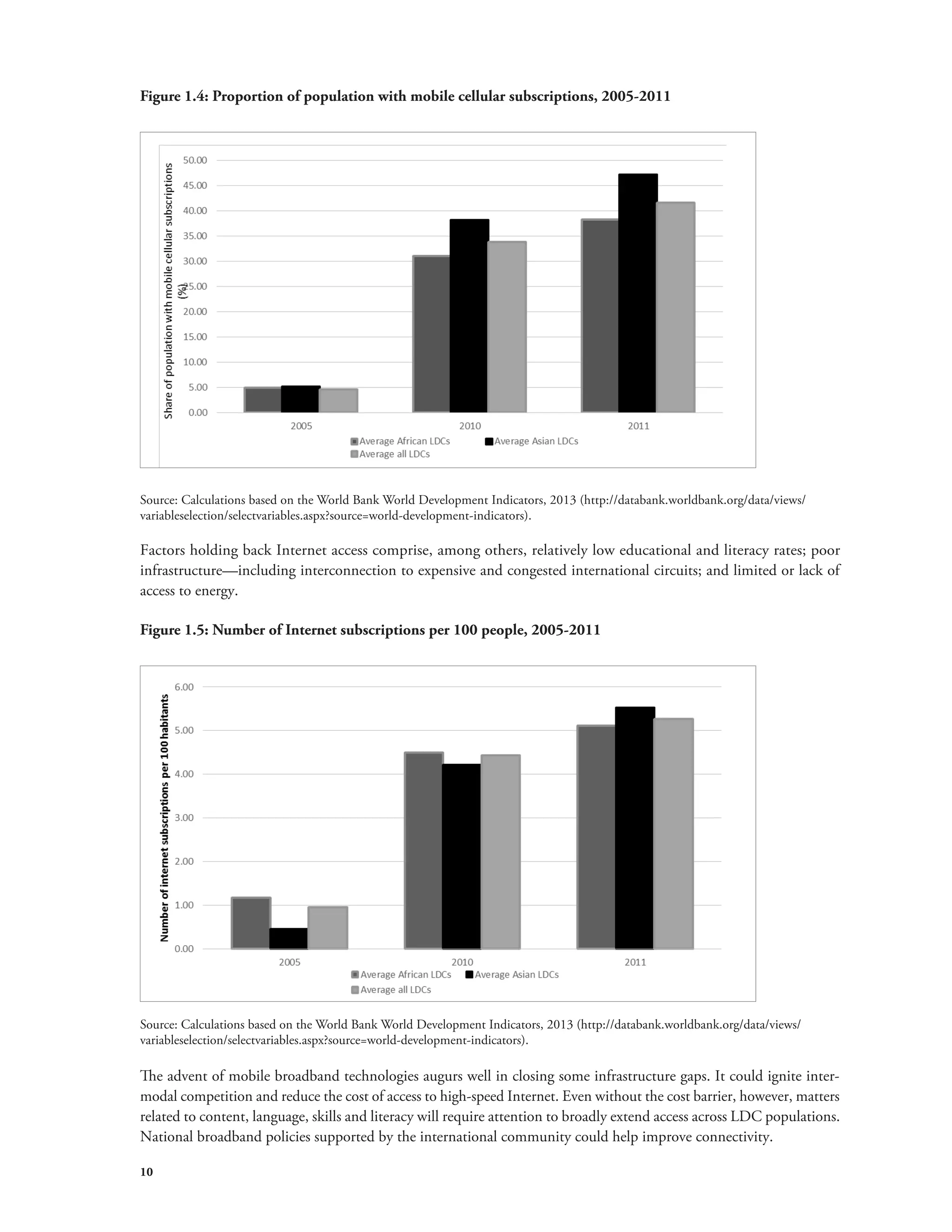

Zambia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stateoftheleastdevelopedcountries2013-140916013100-phpapp02/75/State-of-the-least-developed-countries-2013-129-2048.jpg)