This document summarizes research on creativity, leadership, and management in the UK creative industries. It includes:

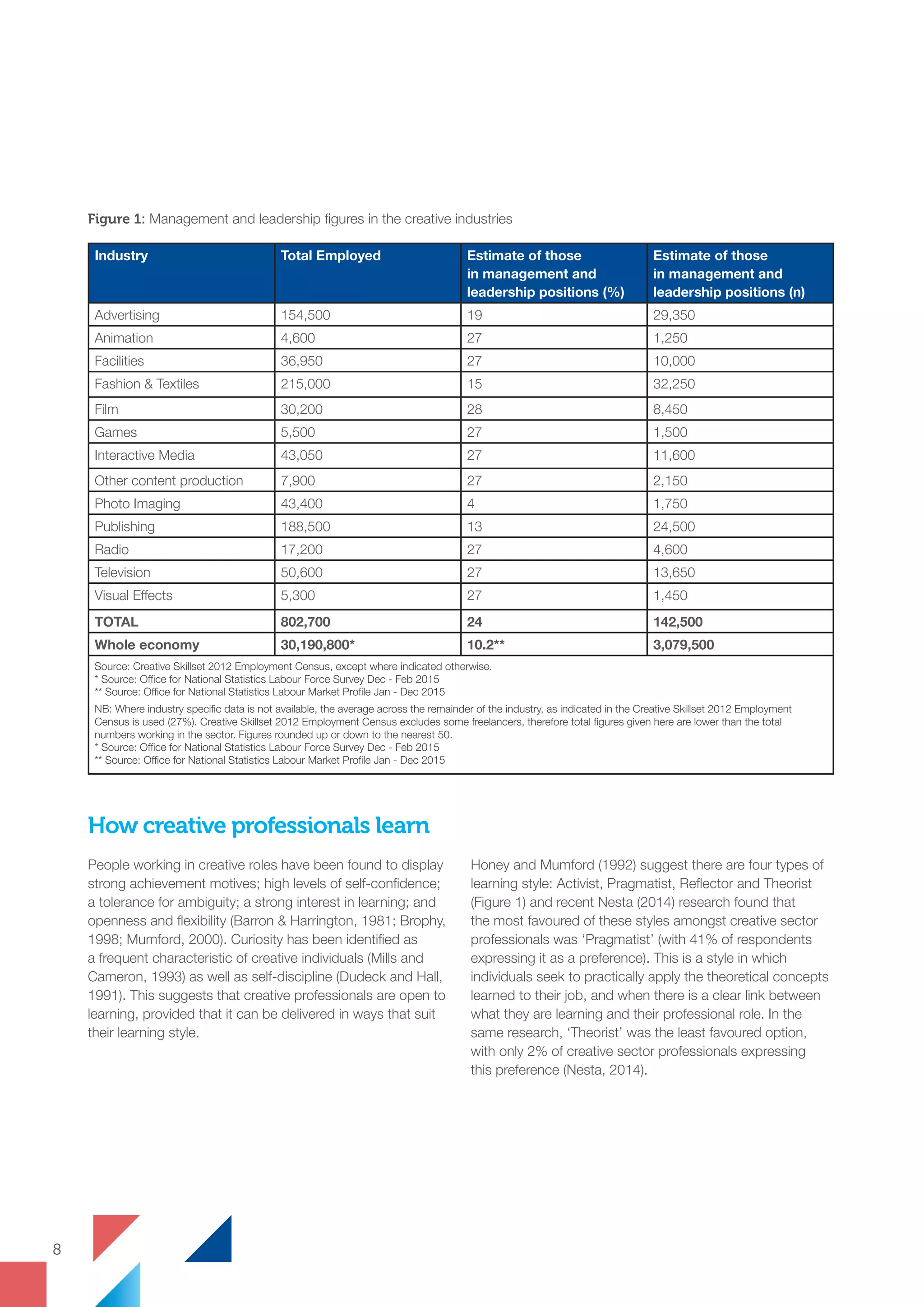

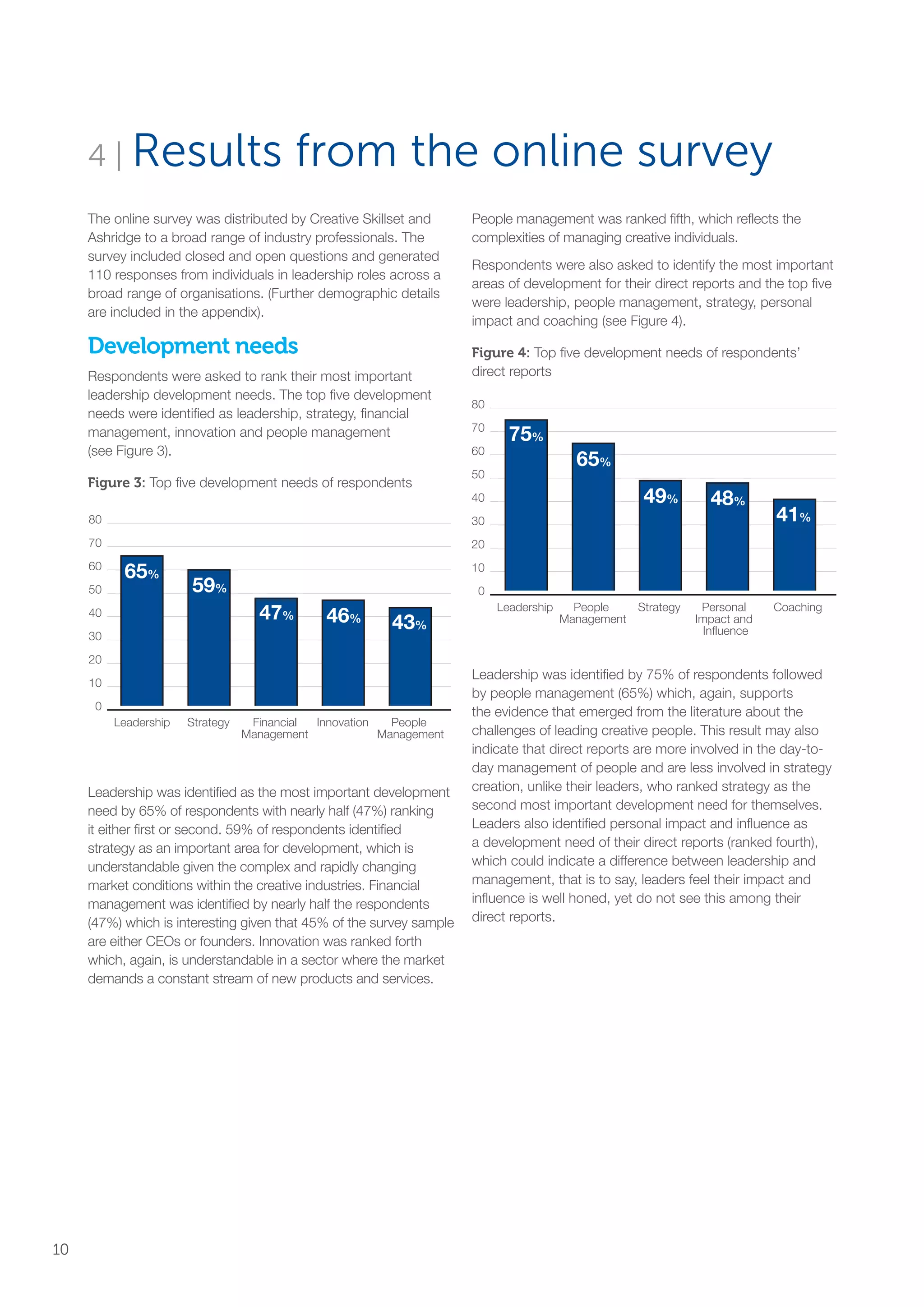

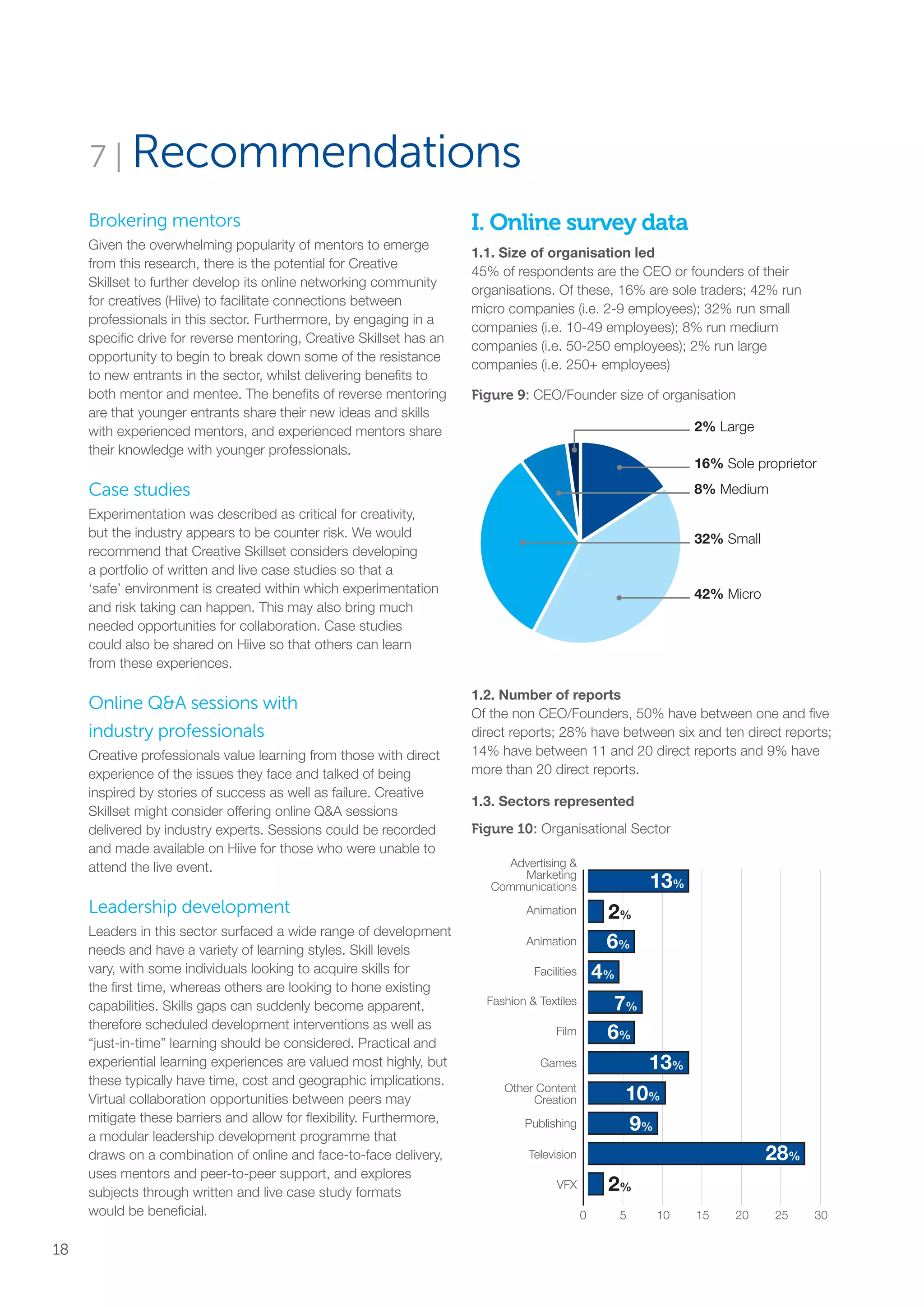

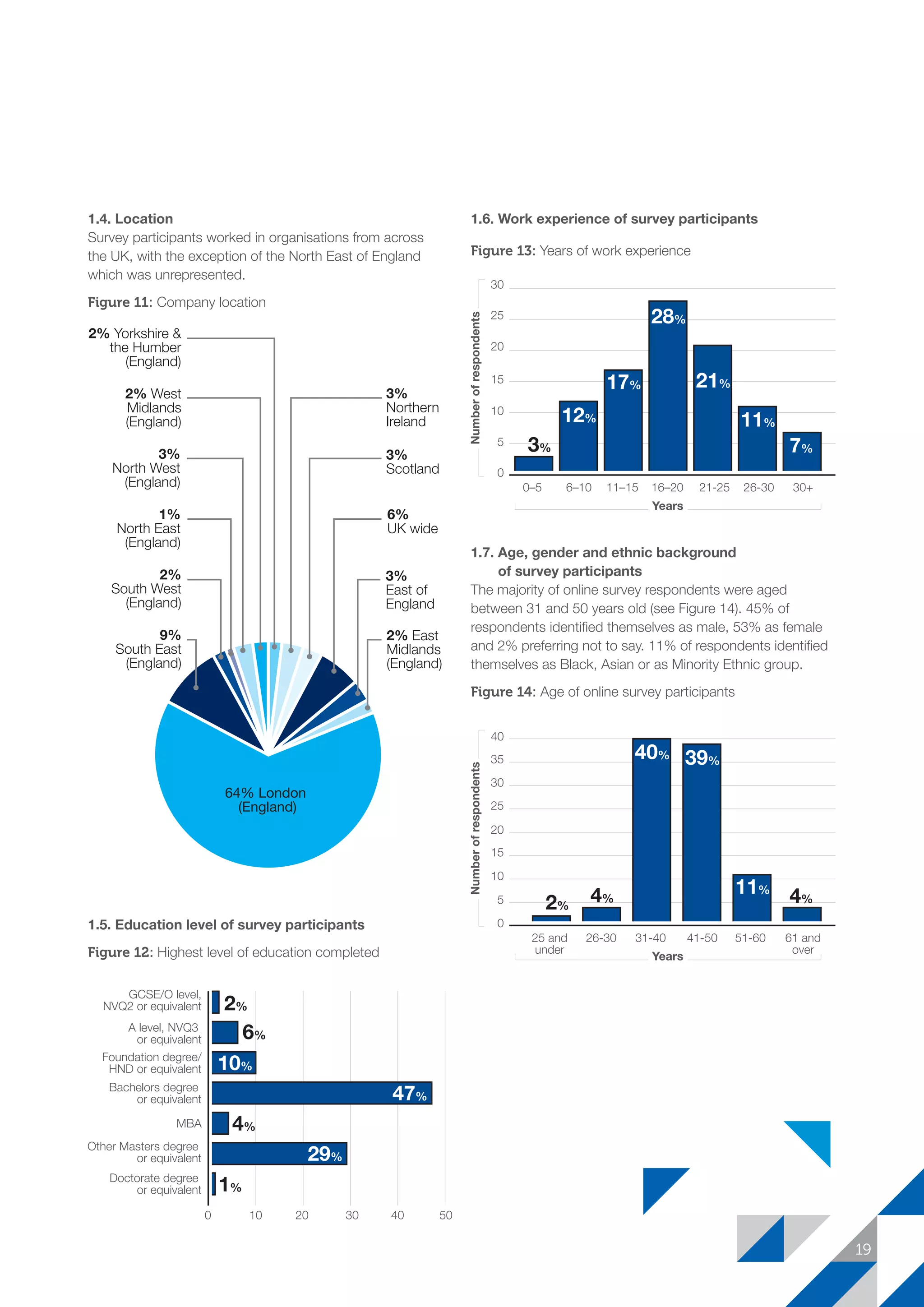

1) An online survey of over 100 creative industry professionals that identified top skills needs as leadership, strategy, financial management, innovation, and people management.

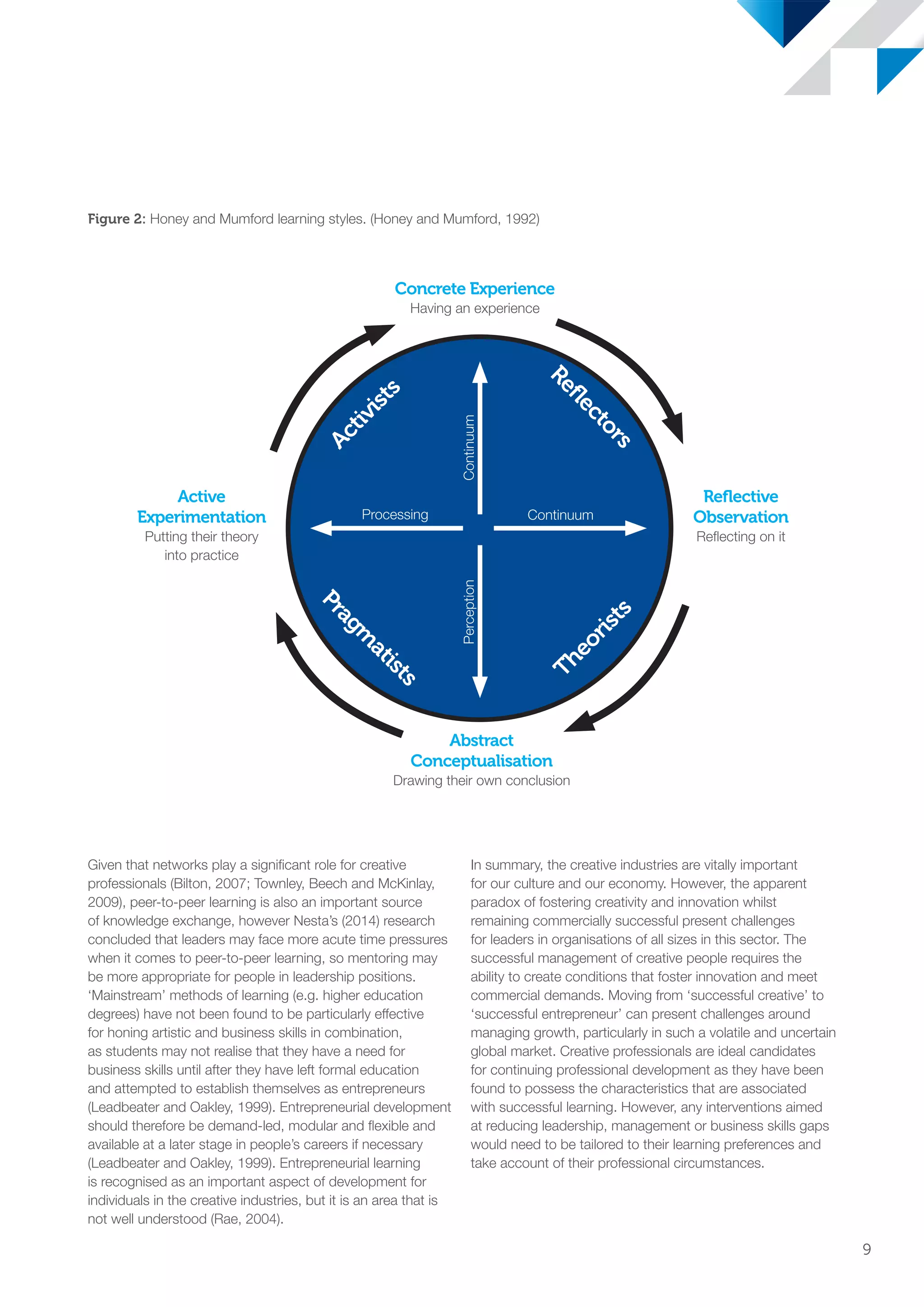

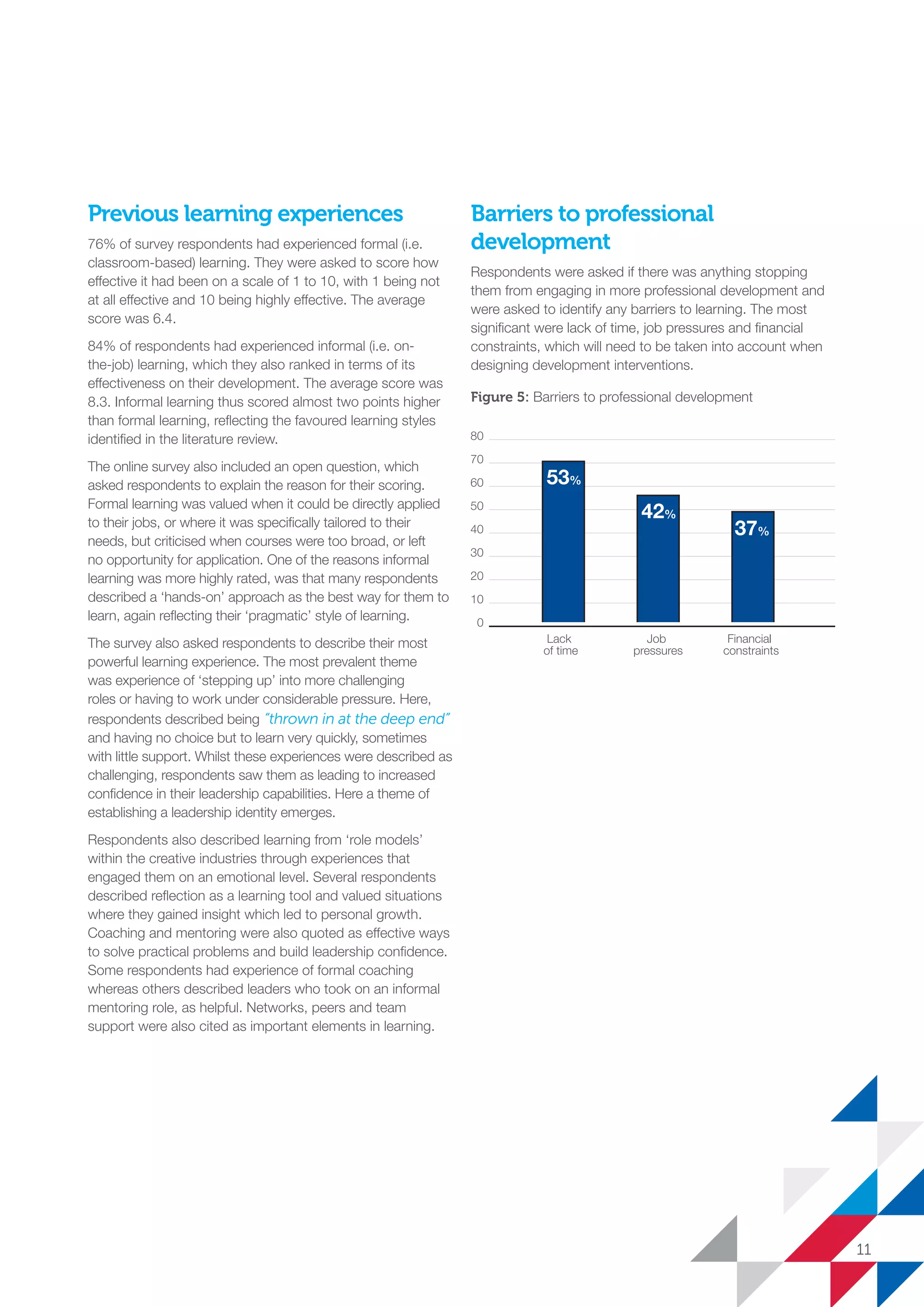

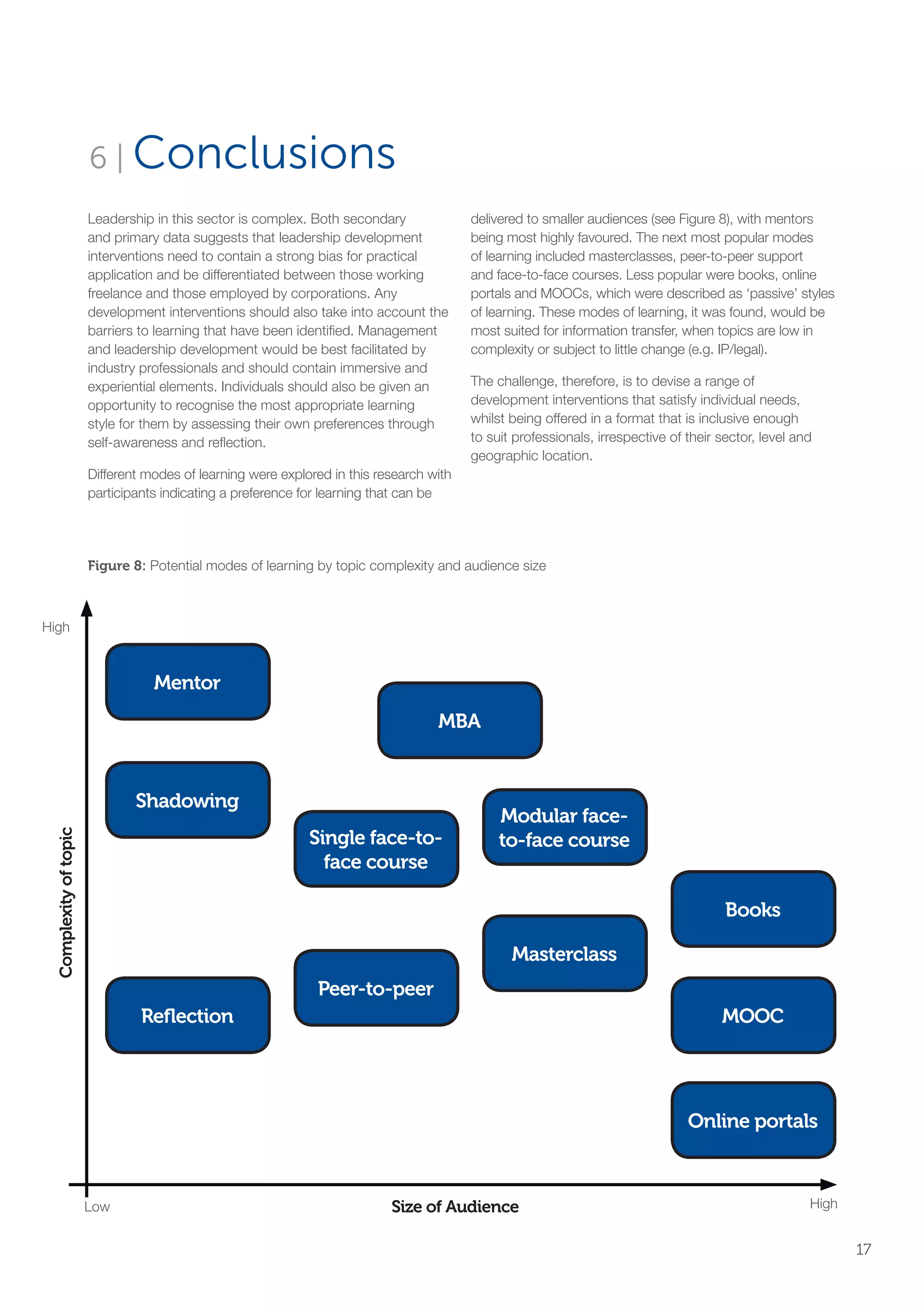

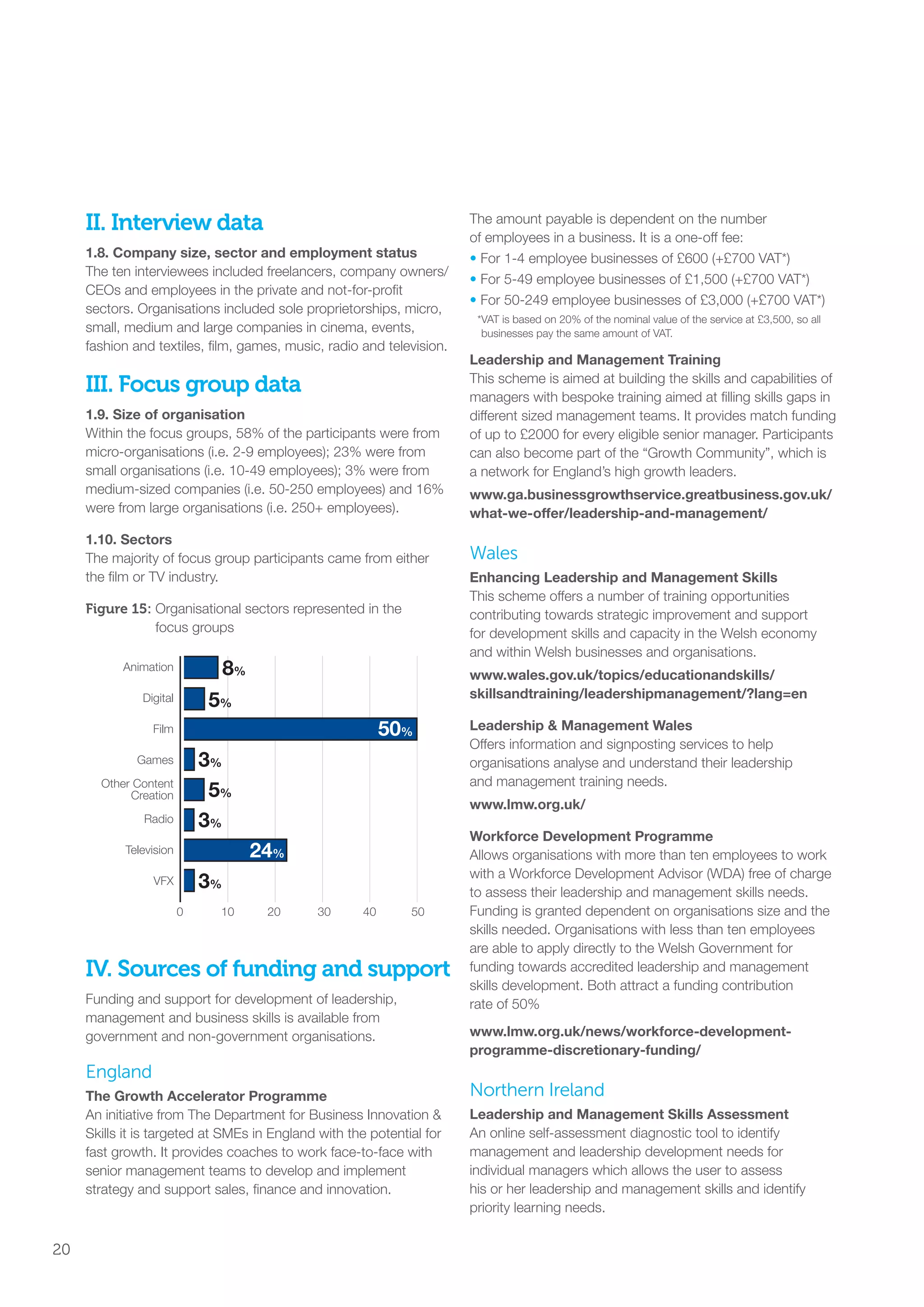

2) Interviews and focus groups with creative professionals that found development is preferred through informal, hands-on learning from mentors rather than formal classroom settings. Barriers to development include lack of time and money.

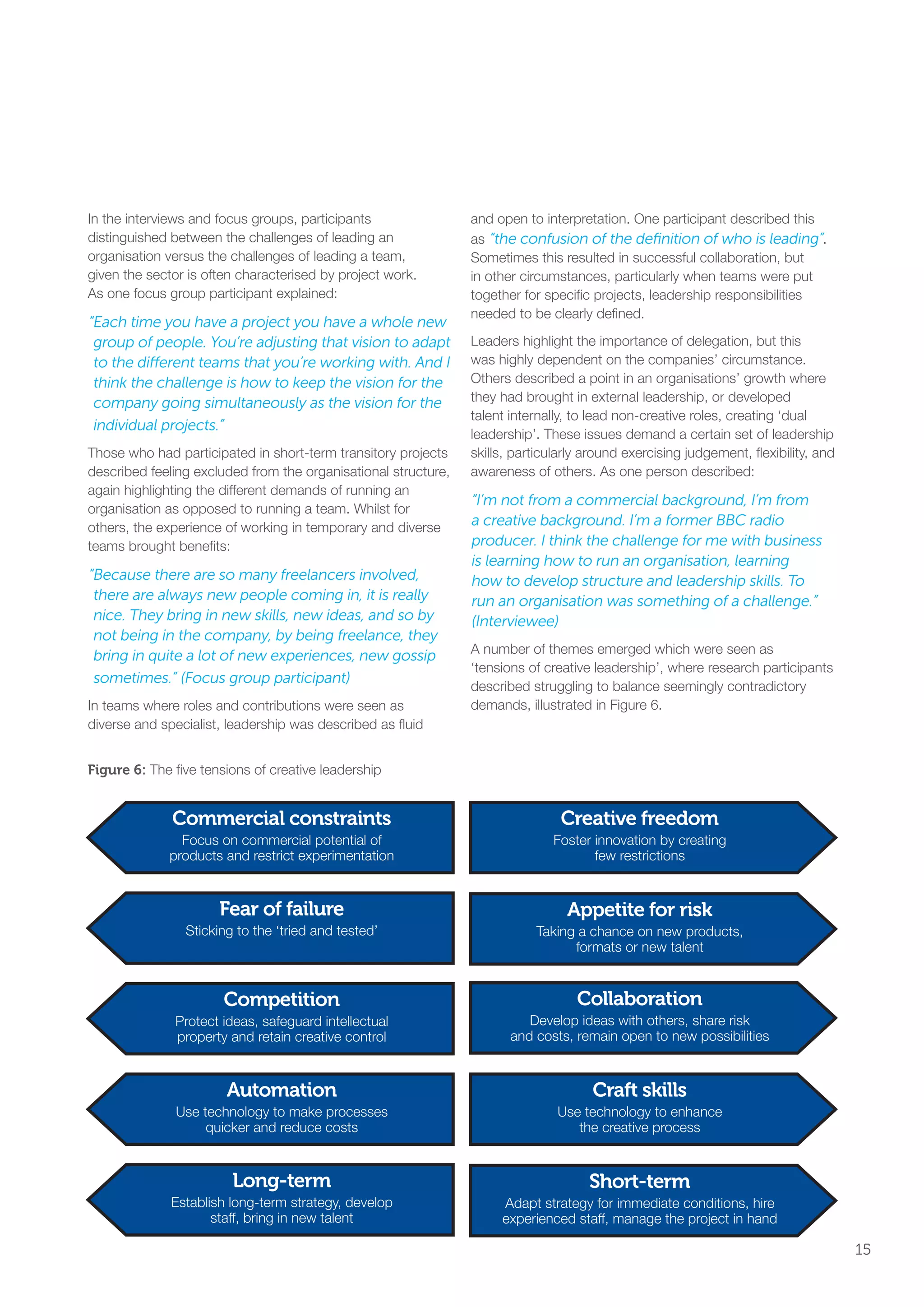

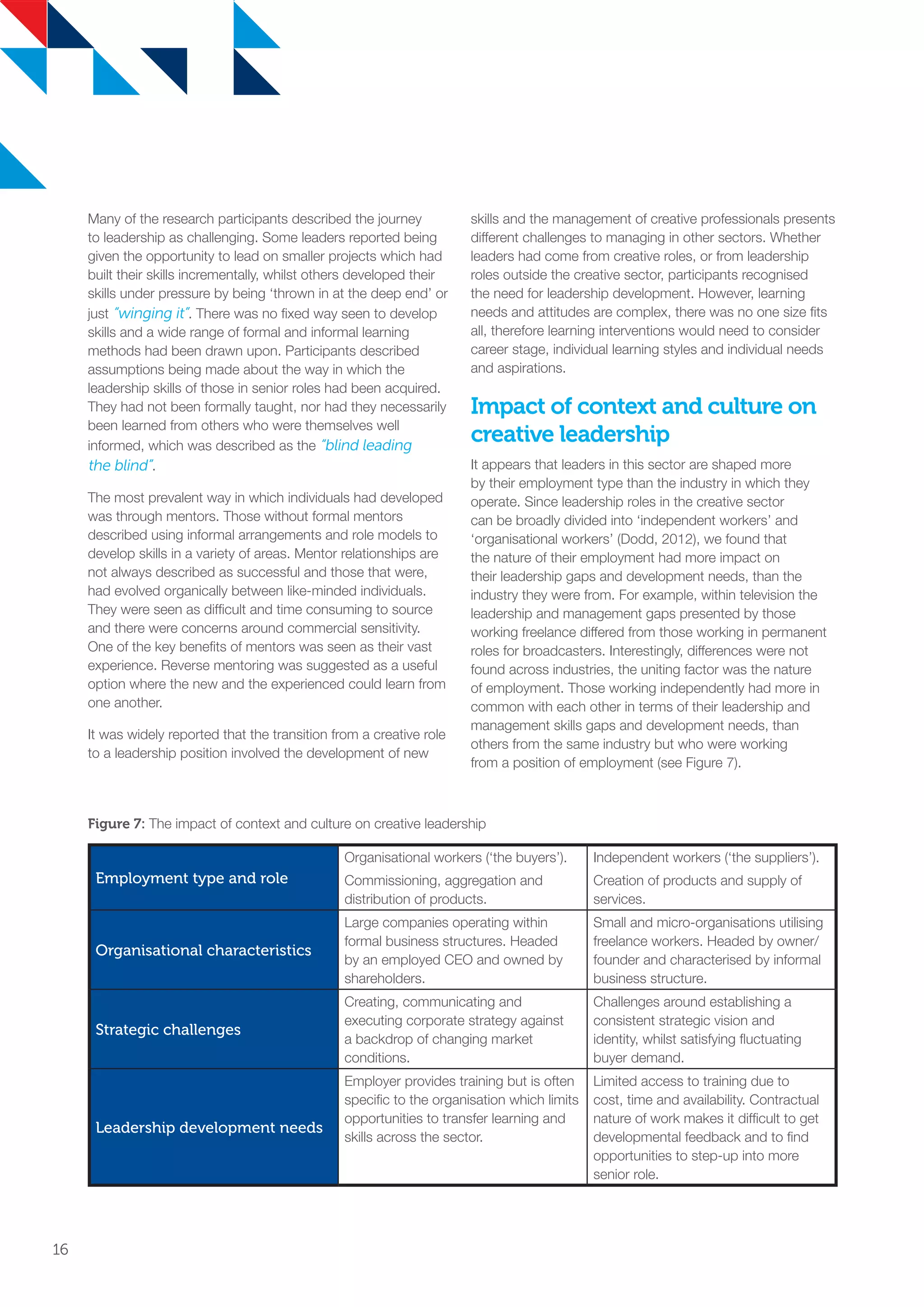

3) Conclusions that leadership requires balancing creativity and commercial demands. The industry is fragmented with many small businesses, and transitioning from creative to entrepreneur poses challenges. Development needs vary between freelancers and those at large companies.