Spatial Database Systems Design Implementation And Project Management 1st Edition Albert Kw Yeung

Spatial Database Systems Design Implementation And Project Management 1st Edition Albert Kw Yeung

Spatial Database Systems Design Implementation And Project Management 1st Edition Albert Kw Yeung

![12 Chapter 1 The Current Status of Spatial Information Technology

sophisticated spatial analysis and modelling. It has to rely on the analytical

functions of a GIS and related spatial analysis software to turn its data into

useful information for different application domains. In many cases, a spatial

database is implemented as a data warehouse that provides the geographical

referencing framework for spatial data used in GIS applications on desktop

computers (see Chapter 6).

It is also important to note that a spatial database can often be used

without a GIS. Although many people use desktop GIS to view spatial

data, new developments in Internet technology and forms of data

representation and presentation (for example, Geography Markup Language

[GML] and Scaleable Vector Graphics [SVG]) have made it possible to view

spatial information in a remote spatial database with the use of an Internet

browser. Processes for data integration and transfer between spatial and non-

spatial databases do not normally require the use of a GIS. Similarly, spatial

decision support is possible without a GIS, but this is achieved with the loss

of GIS-based data visualisation.

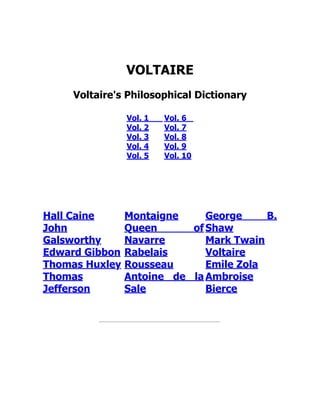

2.4 A Data-based and User-centric Approach to Spatial

Information

Spatial database systems represent a data-based and user-centric

approach to spatial information. Such an approach has three dimensions,

namely stewardship, sharing and commodification, as shown in Figure 1.3.

These components are described as follows:

• Stewardship is concerned mainly with the internal use of spatial

information. Some organisations, in particular those in the public sector,

are mandated by regulations or legislation to collect and maintain a

spatial database as part of their business functions. In such cases, the

objectives and content of the database are tightly coupled with the

respective business requirements and goals of the organisation.

Examples of such spatial databases abound, including land title

registration systems, forestry resource inventories, censuses of

population and housing, inventories of highways and other public

infrastructure such as water mains, electricity and gas distribution

systems, and so on.

• Sharing is a fundamental principle of spatial database systems because

this is the most effective way to minimise the cost and time required for

implementing a spatial database. The primary concern of spatial data

sharing is public access, which entails a delicate balance between the

protection of privacy under freedom of information (FOI) legislation

and the public’s right to access information.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/492234-250522081546-638b8833/85/Spatial-Database-Systems-Design-Implementation-And-Project-Management-1st-Edition-Albert-Kw-Yeung-27-320.jpg)

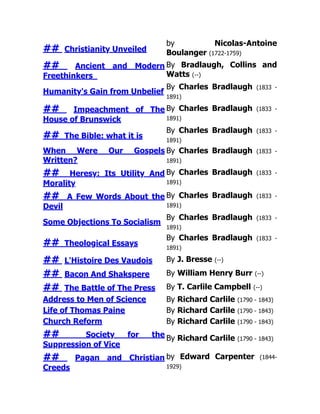

![30 Chapter 2 Concepts and Architecture of Database Systems

be accessed directly by the reading device of the computer. When data in

tertiary storage are required, the storage medium (for example, a digital

video disk [DVD]) is retrieved and loaded into the data reader, and the data

are transferred onto the secondary storage device. The typical access time for

data in secondary storage devices is 10 to 20 milliseconds, whereas it

commonly takes several seconds to access data on tertiary storage devices.

Both secondary and tertiary storage devices are divided into disk blocks.

These are regions of contiguous storage locations containing 4,000 to 16,000

bytes of data. Data are transmitted between secondary or tertiary storage

devices and the main memory by disk blocks, not by data files (see Section

5.2). Database systems control the storage of and access to data in the

storage devices by means of the database engine, as noted Section 2.1. There

are two pieces of data manipulation software in the database engine:

• The buffer manager handles the main memory by allocating the data

read from secondary storage devices to a specific page in the main

memory. It re-uses the page by allocating it to new data coming into the

main memory if the existing data are no longer required.

• The file manager keeps track of the location of data files and their

relationships with the disk blocks. When a specific data file is required,

the file manager locates the disk block(s) in the secondary storage device

containing the file, and sends them to the buffer manager which then

allocates the block(s) of data to a main memory page.

The use of the database engine separates the users from the physical

implementation of the database, and provides them with the processes that

are needed to access the database contents. The separation of applications

from databases is fundamental to all contemporary database design

principles. It allows different groups of users to access different parts of the

database, each using his/her own interface that is designed to do exactly

what is required of the data. All application programs accessing the actual

data files are coordinated and controlled centrally by the database engine,

and the rules of database integrity and validity can be enforced relatively

easily, as explained in the next section.

3.2 Database Security and Integrity Constraints

Closely related to database storage and manipulation are the concepts and

methods of database security and integrity constraints that are designed to

protect the data in the database from being corrupted, compromised, or

destroyed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/492234-250522081546-638b8833/85/Spatial-Database-Systems-Design-Implementation-And-Project-Management-1st-Edition-Albert-Kw-Yeung-43-320.jpg)

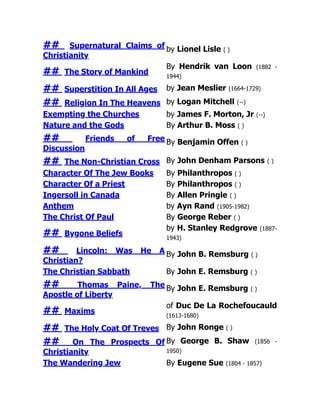

![This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United

States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away

or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License

included with this ebook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the

laws of the country where you are located before using this

eBook.

Title: The Project Gutenberg Collection of Works by Freethinkers

Author: Various

Editor: David Widger

Release date: November 23, 2012 [eBook #41450]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PROJECT

GUTENBERG COLLECTION OF WORKS BY FREETHINKERS ***](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/492234-250522081546-638b8833/85/Spatial-Database-Systems-Design-Implementation-And-Project-Management-1st-Edition-Albert-Kw-Yeung-60-320.jpg)

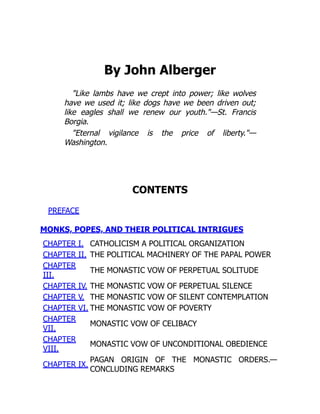

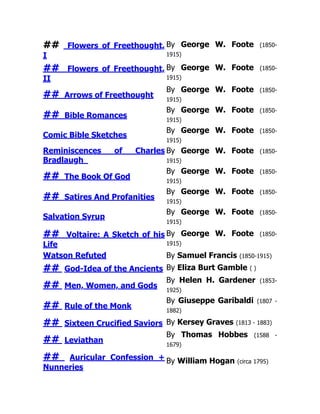

![## Arguments of Celsus By Thomas Taylor (1858 - 1938)

The Innocents Abroad By Mark Twain (1835 - 1910)

## The Entire Forbidden

Gospels

by Archbishop William

Wake (1657 - 1737)

## Is The Bible Worth

Reading

by Lemuel K. Washburn ( )

## The Eliminator; or,

Skeleton Keys

by R. B. Westbrook ( )

A Biographical Dictionary of

Freethinkers

By Joseph Mazzini Wheeler

(--)

## Frauds and Follies of the

Fathers

By Joseph M. Wheeler ( )

## Bible Studies By Joseph M. Wheeler ( )

The Christian Doctrine of Hell By Joseph M. Wheeler ( )

## Warfare of Science with

Theology

by Andrew Dickson White

(1832 - 1918)

## The Ruins

by C. F. [Constantin

Francois de] Volney

(1757-1820)

Letter To Sir Samuel

Shepherd

By Anonymous (--)

The Life of David By Anonymous (--)

The Doubts Of Infidels By Anonymous (--)

The Miraculous Conception By Anonymous (--)

Christian Mystery By Anonymous (--)

What it is Blasphemy to Deny By Annie Besant (1847 - 1933)

Humanity's Gain from

Unbelief

By Charles Bradlaugh (1833 -

1891)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/492234-250522081546-638b8833/85/Spatial-Database-Systems-Design-Implementation-And-Project-Management-1st-Edition-Albert-Kw-Yeung-75-320.jpg)