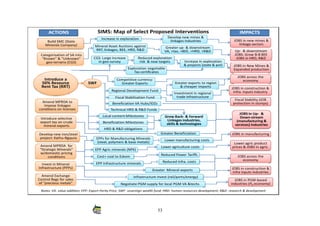

This document discusses maximizing the developmental impact of South Africa's mineral assets. It reviews South Africa's significant mineral resources and the country's history of mining. It discusses the ANC's policies regarding ensuring mineral resources benefit South Africans. The document conducted research including international case studies and stakeholder workshops. It proposes interventions in areas like ownership and control, governance, economic linkages, and regional impact to better leverage mineral wealth for growth, employment and equitable development in South Africa.

![are not viable due to an isolated location, or specific climate conditions (e.g. desert),

then relocation plans need to be developed.

9) LED‐ Mining Charter: Failure to comply with the community and worker conditions of

the Charter should trigger a suspension of the mining licence and, if not rectified

within a reasonable period, the concession should be cancelled. The MPRDA should be

amended to cater for this.

2.4 Proposals to Enhance the Developmental Impact through Regional Integration:

1) Larger markets for Linkages Industries: Although the South African minerals sector

constitutes a relatively large market for mineral inputs industries (backward

linkages), the southern African region (SADC) has a rapidly growing minerals inputs

market and significant future mineral potential. Most of the countries surveyed with

well‐developed linkages either have large domestic markets (China, Brazil) or are

part of large regional markets such as EU, ASEAN and Mercosur. In this regard the

52nd

ANC National Conference resolved to build “stronger economic linkages across

the continent of Africa as a whole as a basis for increasing our market size through

deepened economic integration”51

. The viability of establishing supplier and

beneficiation industries (backward & forward linkages) would be substantially

enhanced by regional integration. “In this regard a special facility should be created

to promote investment in the sub‐continent”52

, through the proposed SWF Regional

Development Fund to invest in long‐term trade infrastructure across the southern

African region. Many countries in the region are displaying robust growth due to the

minerals “super‐cycle”. The NGP notes that “South Africa cannot succeed with

regional development without strong partnerships with other countries on the

continent. [The NGP] proposals centre on a strategy for improving logistics, with

clear priorities and timeframes... [including] ...measures to expand regional

investment and trade and develop integrated supply‐chains and industrial corridors

particularly in mining and agro‐processing; and reducing regulatory obstacles to

trade and travel.”53

In this regard industrial linkages potential would be greatly

enhanced by larger (regional) markets (economies of scale) and our government

should be mandated to progress the extension of membership of the Southern

African Customs Union (SACU), with a reassessment of the relevant import tariff

lines (infant industry protection), and the IDC should develop viable linkage industry

investments in other member countries to facilitate equitable benefits. This should

be pursued together with the proposed Regional Development Fund (trade related

infrastructure) to facilitate intra‐regional trade in mining inputs and outputs.

2) Competitive Mineral Feedstock Prices: A larger (regional) market could also facilitate

competitive pricing of mineral‐based intermediate products (and manufacturing

jobs) as “...the small size and relative isolation of our economy leads to monopolies

in certain sectors which could be overcome by increasing regional economic

51

See Annexure – ANC 52nd

Congress Economic Transformation Resolution, 2.12

52

RDP 2004, op cit, see Annexure, #12.

53

EDD 2010, NGP, p14.

50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sims-141202223439-conversion-gate01/85/Sims-50-320.jpg)