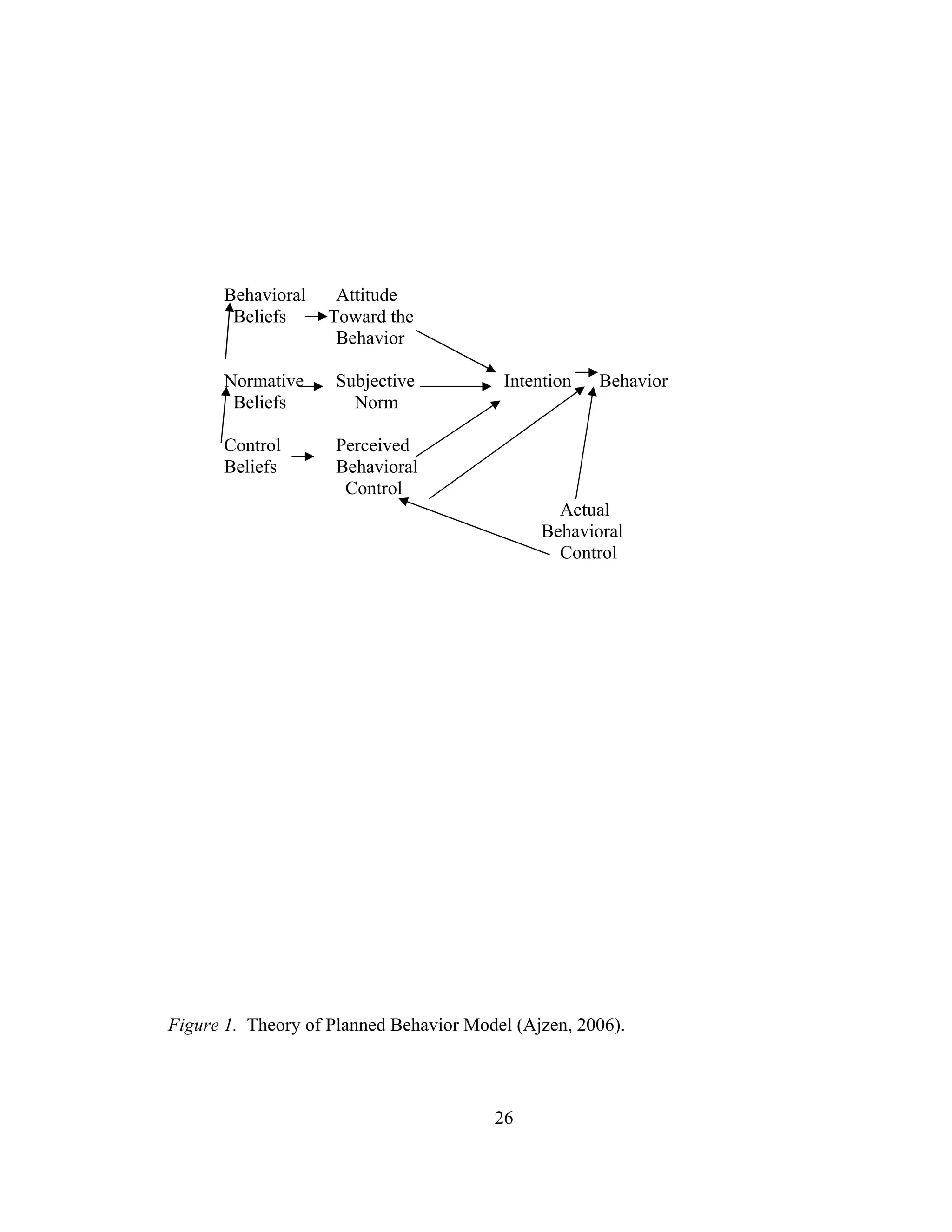

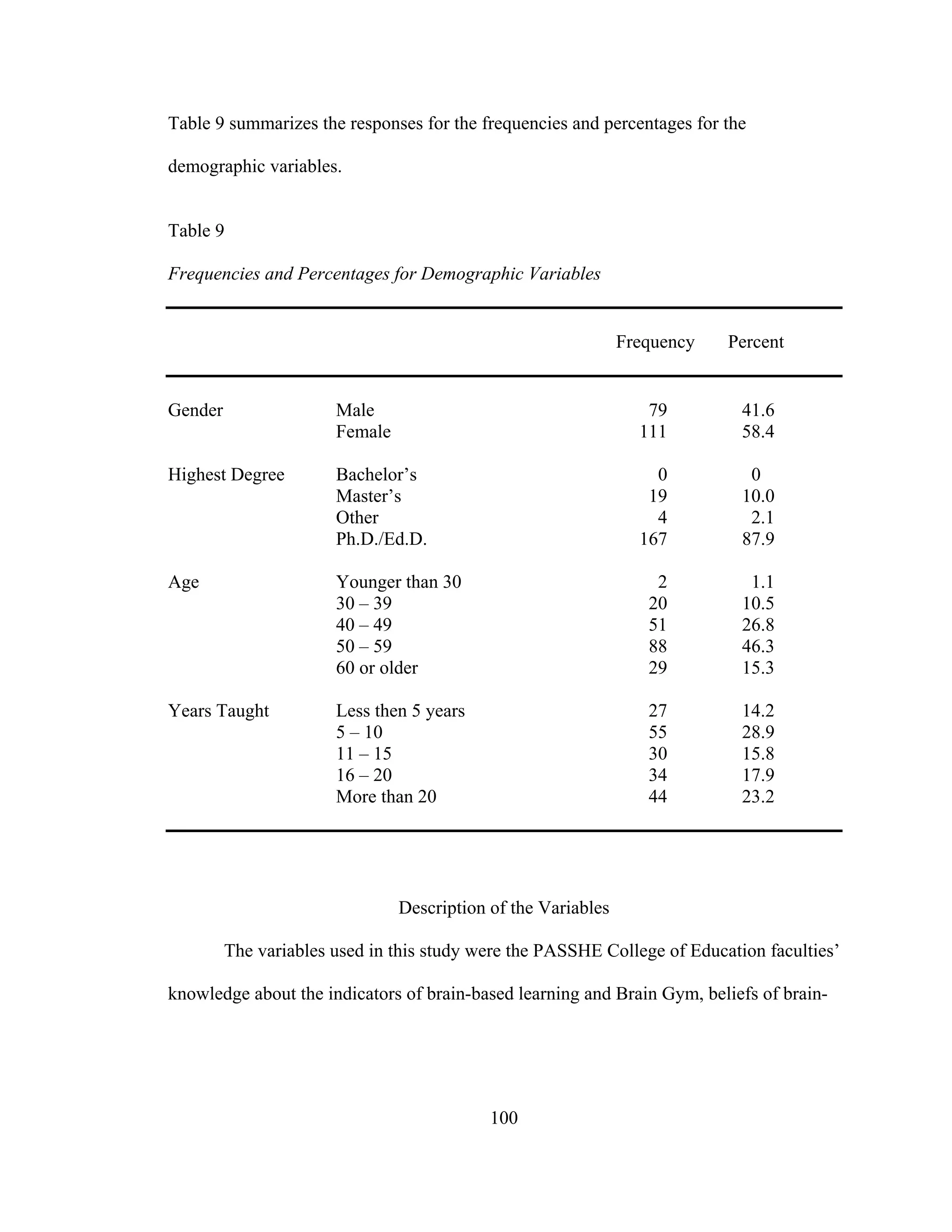

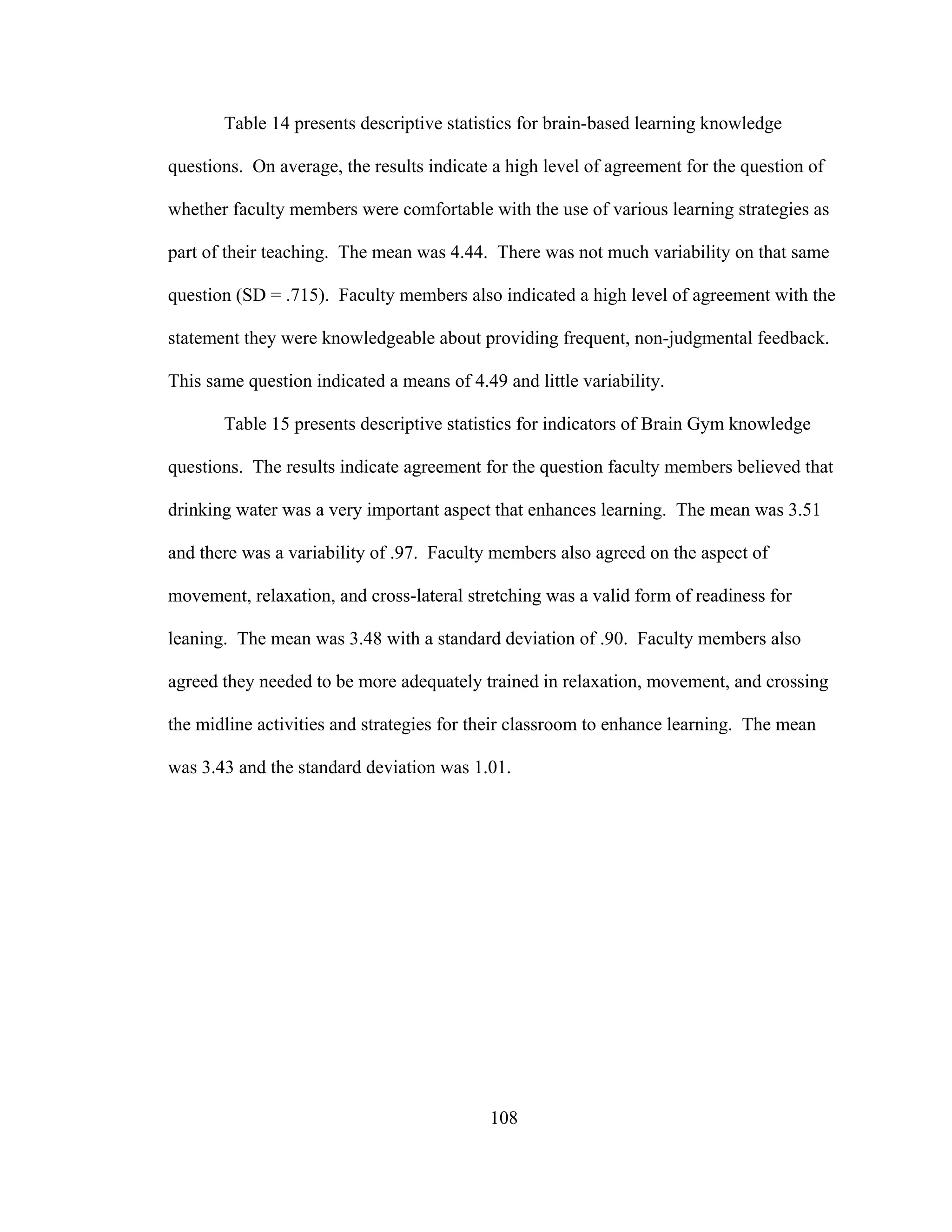

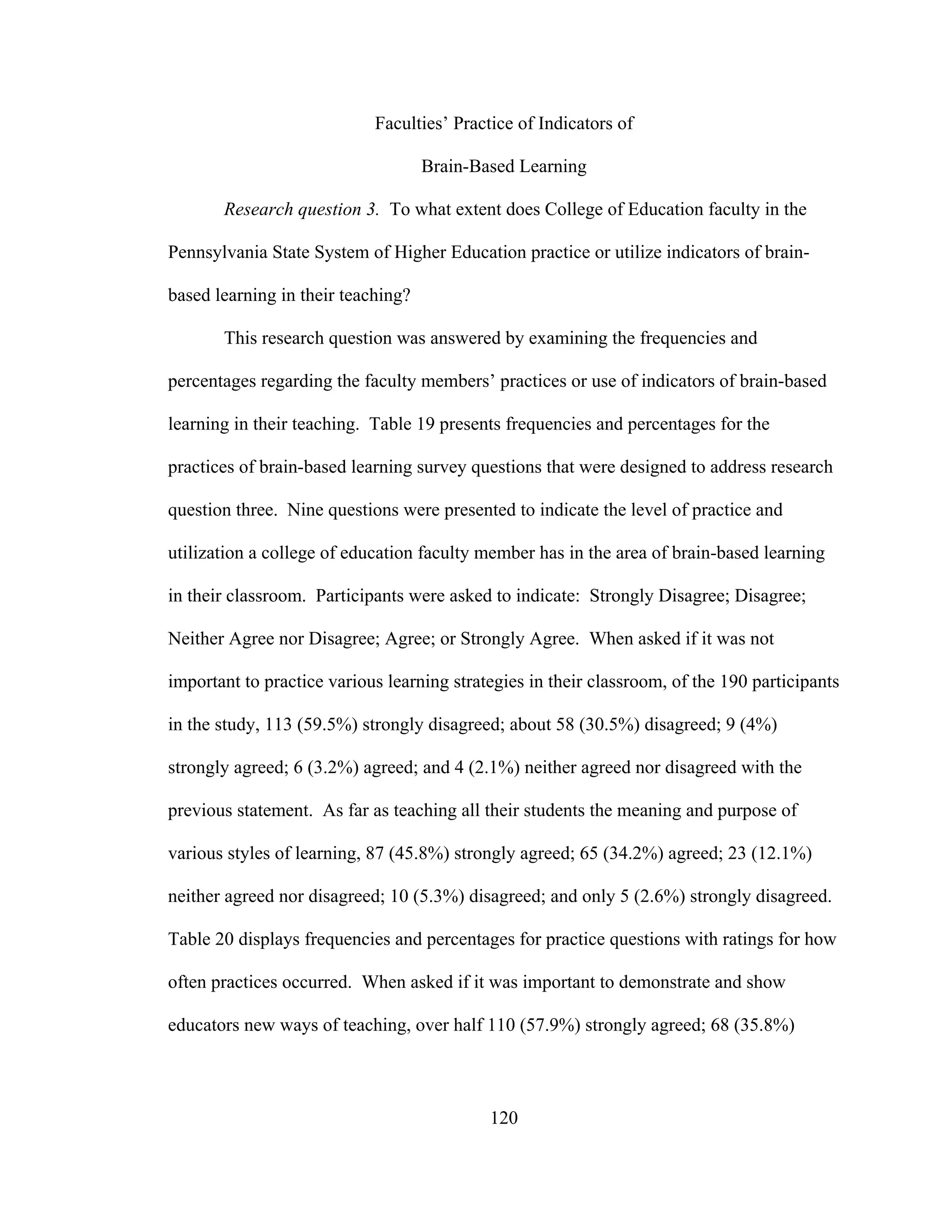

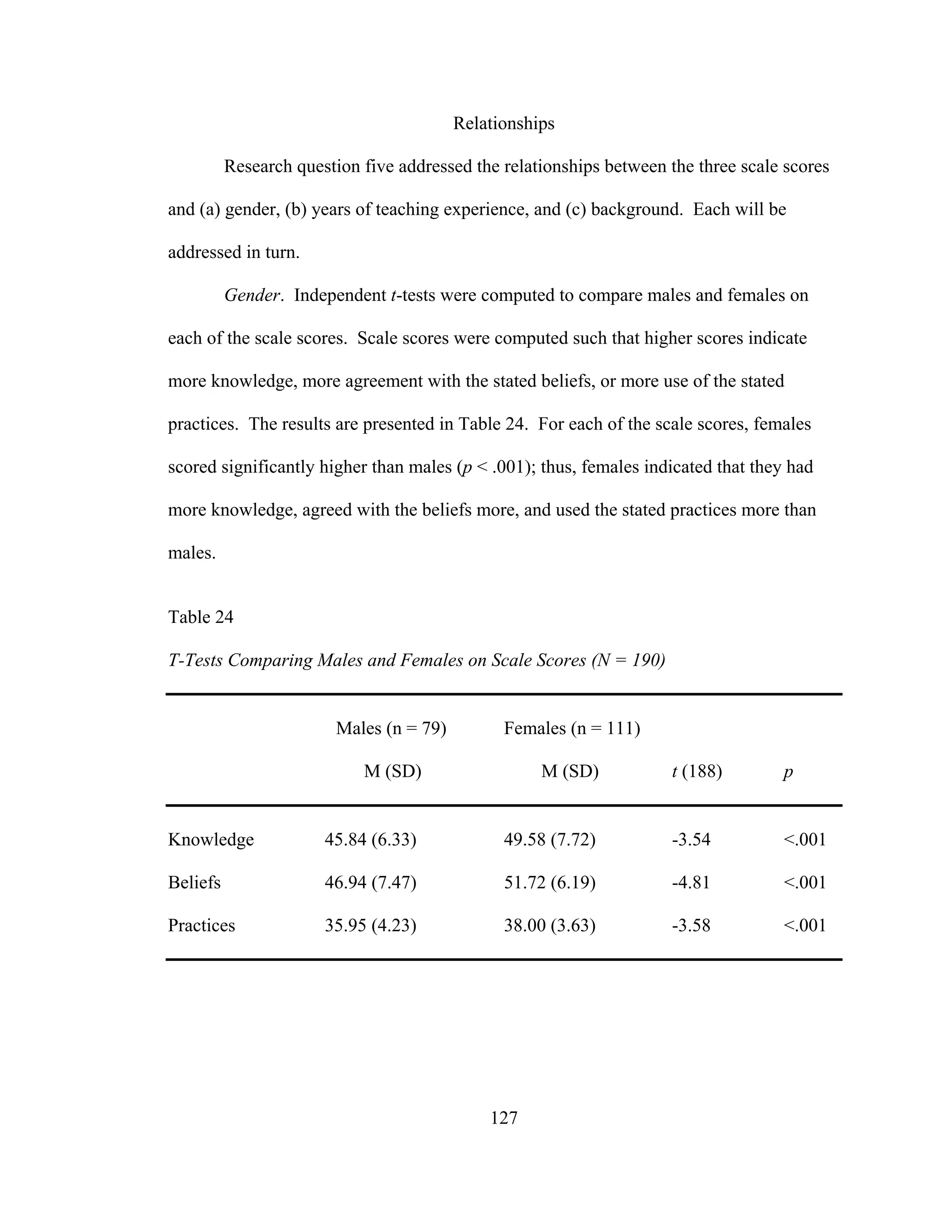

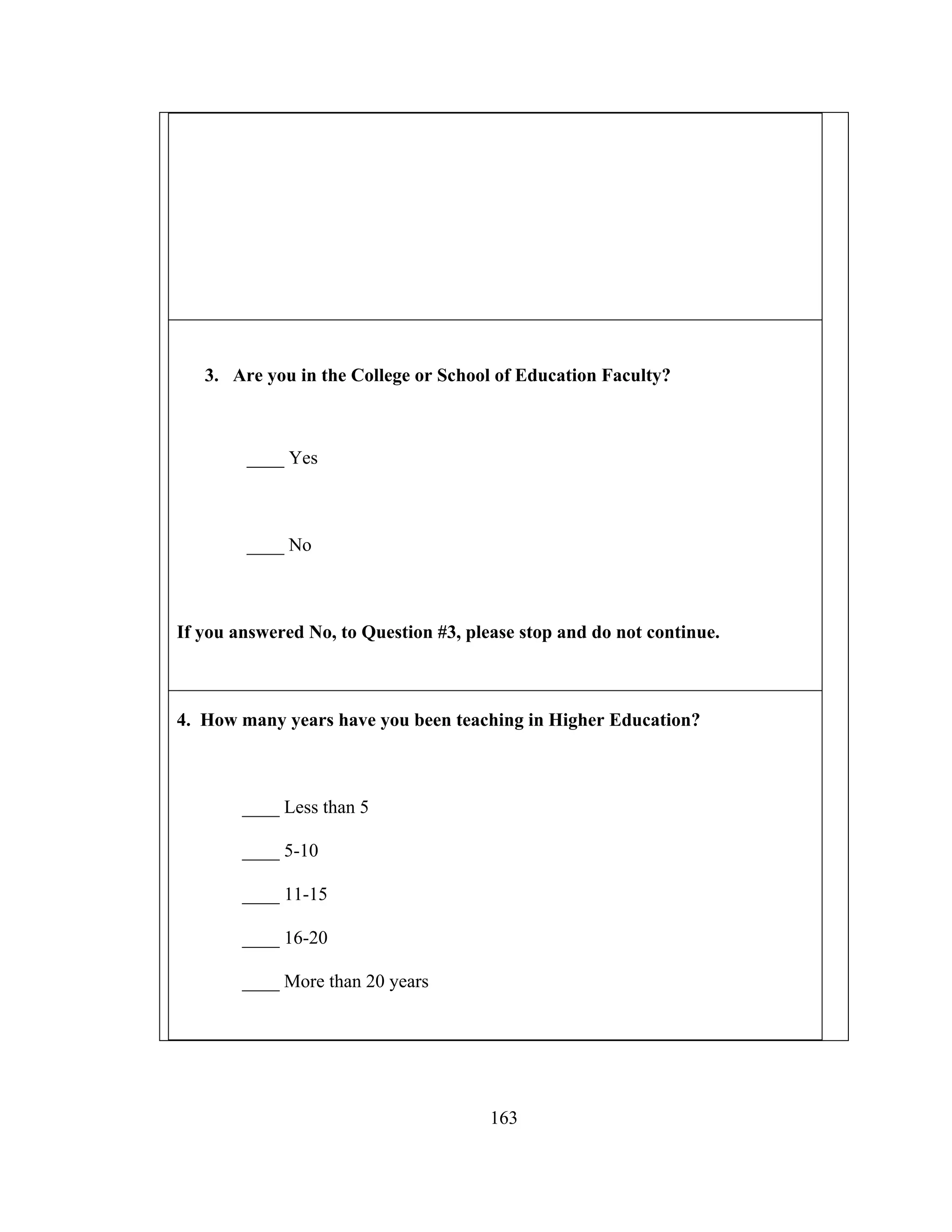

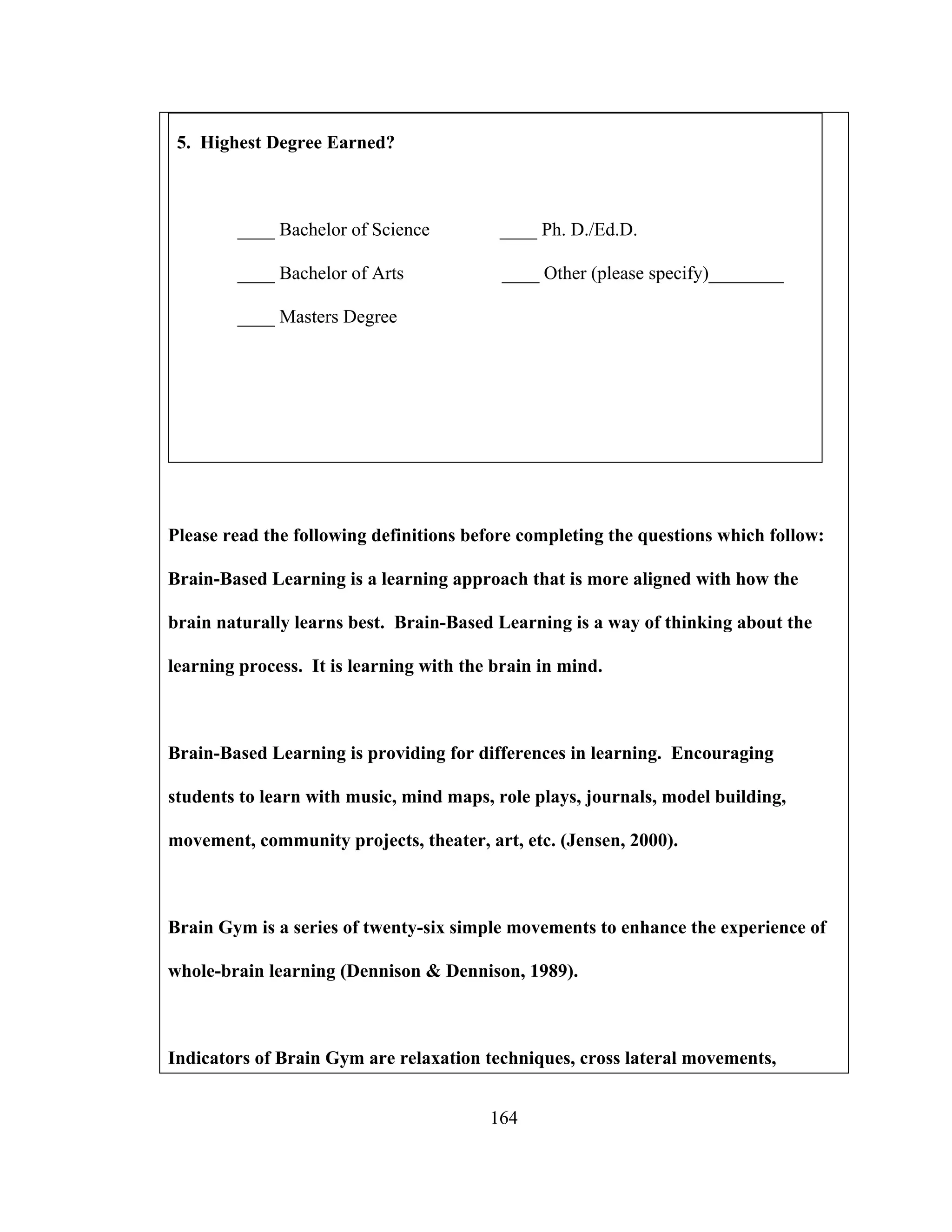

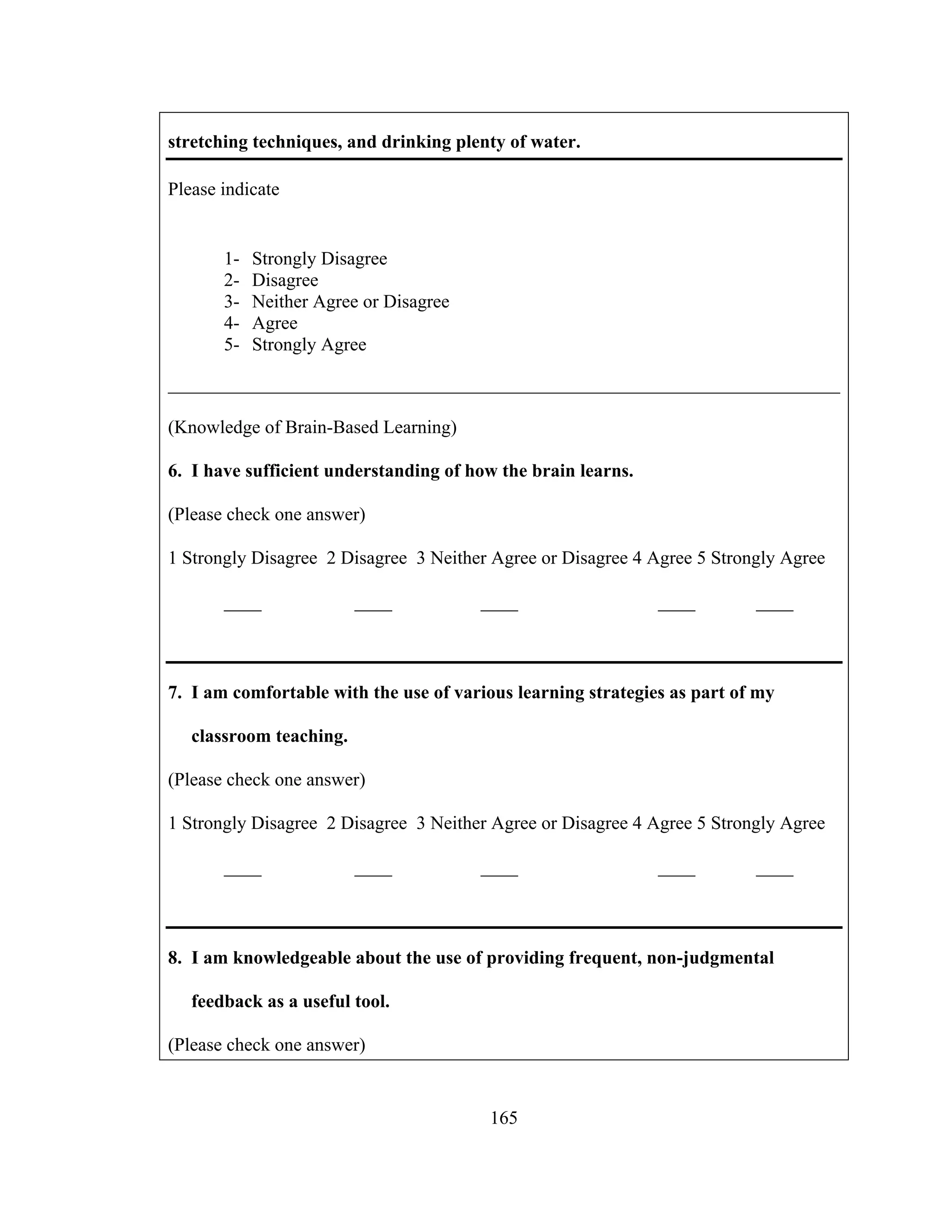

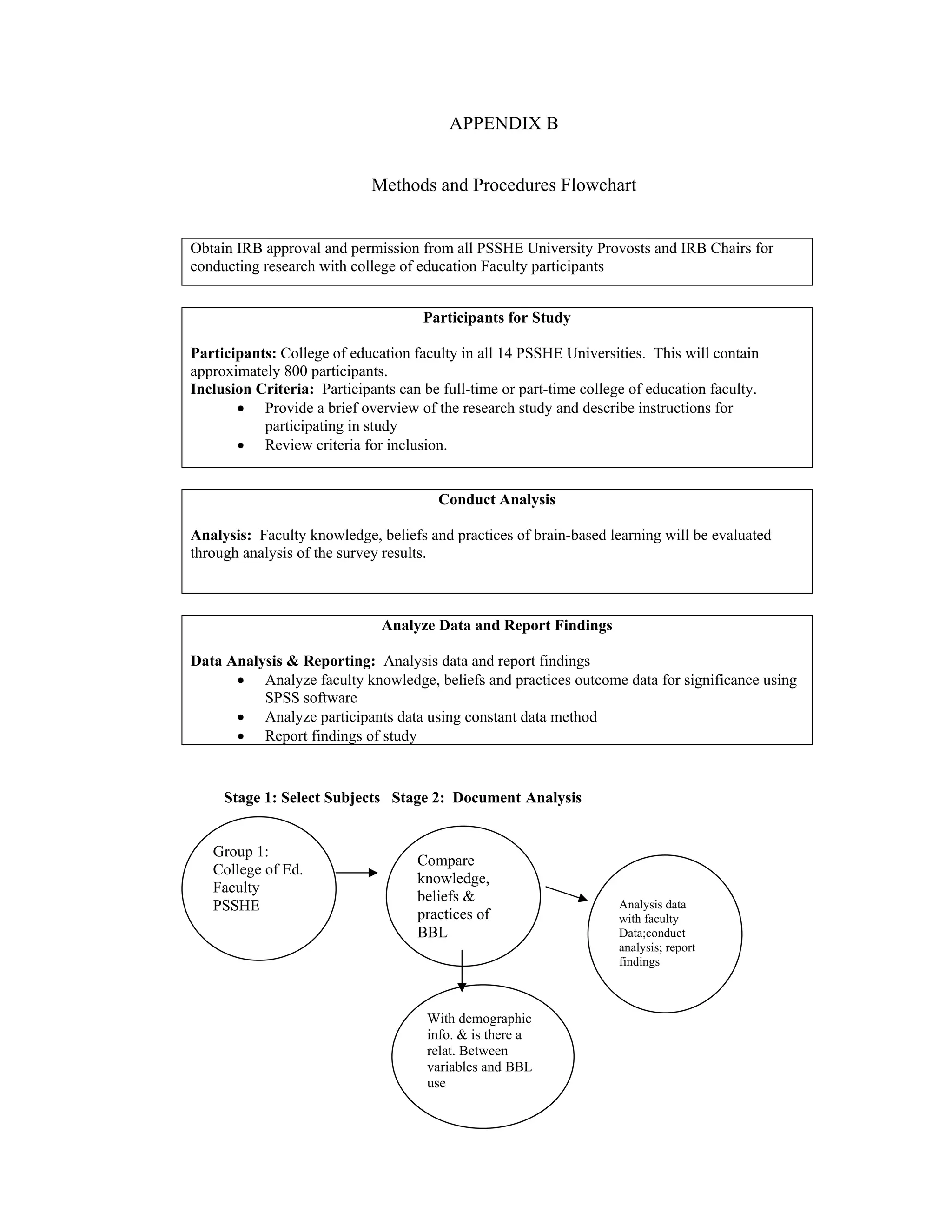

This document is a dissertation submitted by Shelly R. Klinek to Indiana University of Pennsylvania examining faculty knowledge, beliefs, and practices regarding brain-based learning. The dissertation provides background on brain-based learning and related concepts like multiple intelligences and cognitive learning theory. It then reviews literature on brain anatomy, brain-based techniques, factors influencing faculty adoption of new practices, and a theory of planned behavior model. The methodology section describes a quantitative survey distributed to faculty in the Pennsylvania state university system to understand their experiences with and use of brain-based learning.