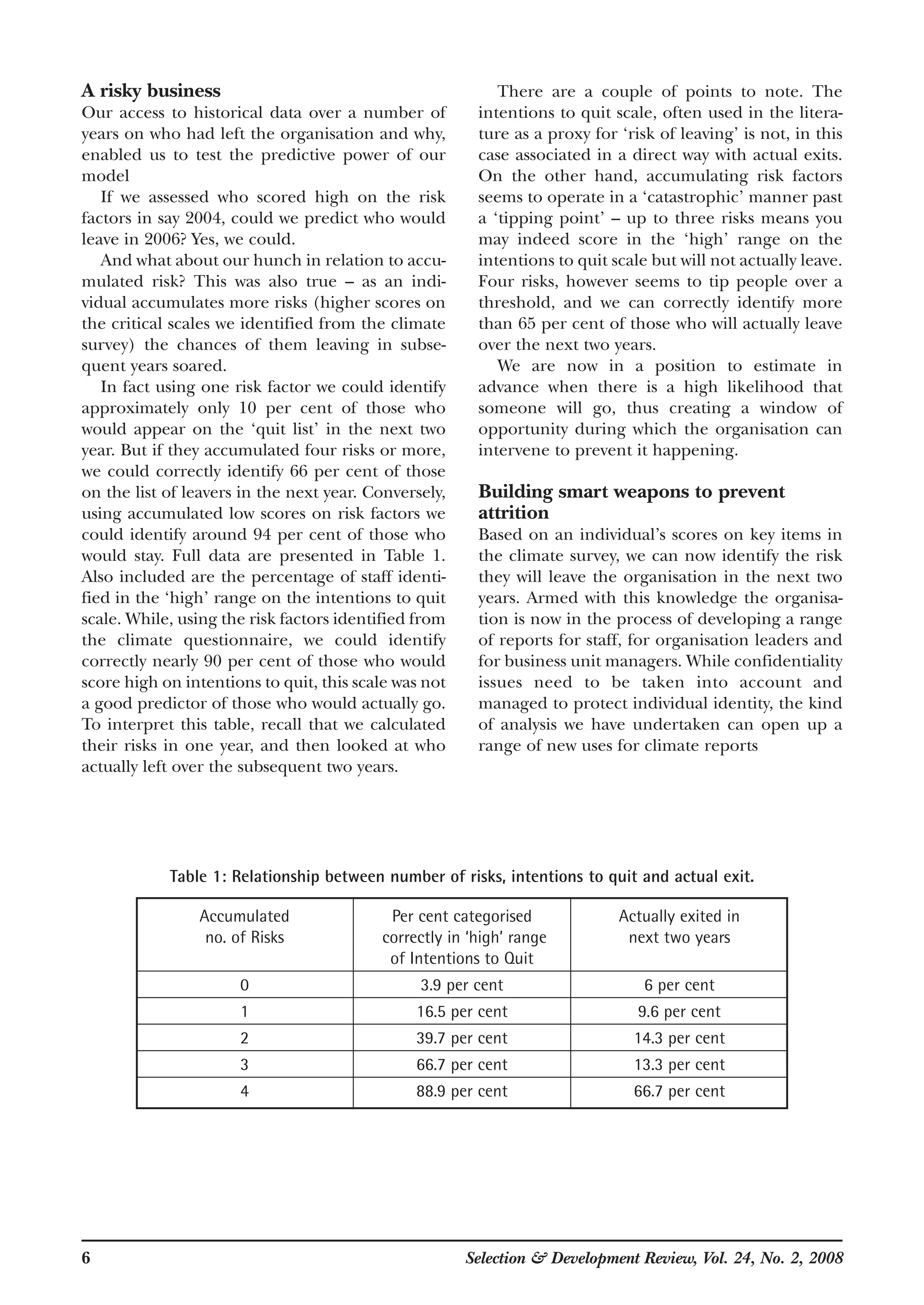

1) An organization developed an early warning system to predict when valued employees may leave by analyzing trends in employee satisfaction surveys.

2) The system involved isolating factors from past satisfaction surveys that correlated with employees' intentions to leave, modeling these factors to confirm their impact, and creating scales to predict which individual employees were most likely to leave based on their survey responses.

3) The early warning system aimed to identify potentially disengaged employees earlier in order to intervene with measures like renegotiating responsibilities before they decided to leave the organization.

![balanced written reports for: (a) the candi-

date; and (b) the client – where the assess-

ment is being carried out for a third party.

5.2 Provides non-judgemental oral feedback of

results to candidates with methodical use of

the feedback interview to help confirm/

disconfirm hypotheses generated from the

pattern of individual test results.

5.3 Provides an indication to the candidate and

to the client (when there is a third party

involved) of the status and value of the

information obtained and how it relates to

other information about the candidate's

personality.

Similar issues relate to the EFPA (European

Federations of Psychology Associations)

Standards for Test Use. In EFPA standard 1.1.

‘Act in a professional and ethical manner’ it is

noted that:

‘1.1.d. You must ensure that you conduct

communications and give feedback with due

concern for the sensitivities of the test taker

and other relevant parties.’

Providing feedback is identified as an ‘essential

skill’ for EFPA Standard 2.5 ‘Communicate the

results clearly and accurately to relevant others’:

‘2.5.b. You must ensure that you discuss results

with test takers and relevant others in a

constructive and supportive manner.’

Again, the importance of having the necessary

skills and competence to conduct feedback is

stressed, but nowhere is it stated that feedback

must always be given, whatever the circum-

stances.

We find the same emphasis on how feedback is

given, rather than whether it is given, in the ITC

(International Test Commission) Test Use

Guidelines in Section 2.8. ‘Communicate the

results clearly and accurately to relevant others’.

This simply states that:

‘Competent test users will: [2.8.10] Present

oral feedback to test takers in a constructive

and supportive manner.’

Within Appendix A of the ITC Guidelines

(Guidelines for an outline policy on testing) it is

noted that a policy on testing should cover,

amongst other things, the provision of feedback

to test takers. It goes on to say that relevant

parties (which include test takers) need to have

access to and be informed about the policy on

testing and that responsibility for any organisa-

tion’s testing policy should reside with a quali-

fied test user who has the authority to ensure

implementation of and adherence to the policy.

Furthermore, in Appendix B, guidelines are

provided for developing ‘contracts’ between

parties involved in the testing process. This states

that the contract between the test user and test

takers should be consistent with good practice,

legislation and the test user’s policy on testing.

‘Test users should endeavour to:

b.5 inform test takers prior to testing about the

purpose of the assessment, the nature of

the test, to whom test results will be

reported and the planned use of the results;

b.6 give advance notice of when the test will be

administered, and when results will be avail-

able, and whether or not test takers or

others may obtain copies of the test, their

completed answer sheets, or their scores;

b.10 ensure test takers know that they will have

their results explained to them as soon as

possible after taking the test in easily under-

stood terms;’

The footnote to b.6 is actually very important in

that it states: ‘While tests and answer sheets are

not normally passed on to others, there is some

variation between countries in practice relating

to what test takers or others are permitted to

have. However, there is much greater variation in the

expectations of test takers concerning what information

they will be given [my italics]. It is important that

contracts make clear what they will not be given

as well as what they will.’

What is emerging here is an emphasis on the

need to establish a clear understanding with the

test taker before they take the test regarding

what they can expect in terms of feedback after-

wards. This becomes much more explicit on the

current draft of the standard being developed by

the International Standards Organization (ISO)

for assessment in work and organisational

settings, which addresses feedback as follows:

‘Whether feedback is provided or not and the

nature of that feedback, where it is to be

provided, shall be defined within the context

of organisational , legal, and cultural norms.

The people who are being assessed shall have

been notified of whether or not feedback will

be provided and the nature of the feedback,

if any, prior to the assessment taking place.’

Selection & Development Review, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2008 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8d7e6f4d-8dd1-4b88-96ec-d453e8407395-161108121451/75/SDR-24_2-proof-21-2048.jpg)