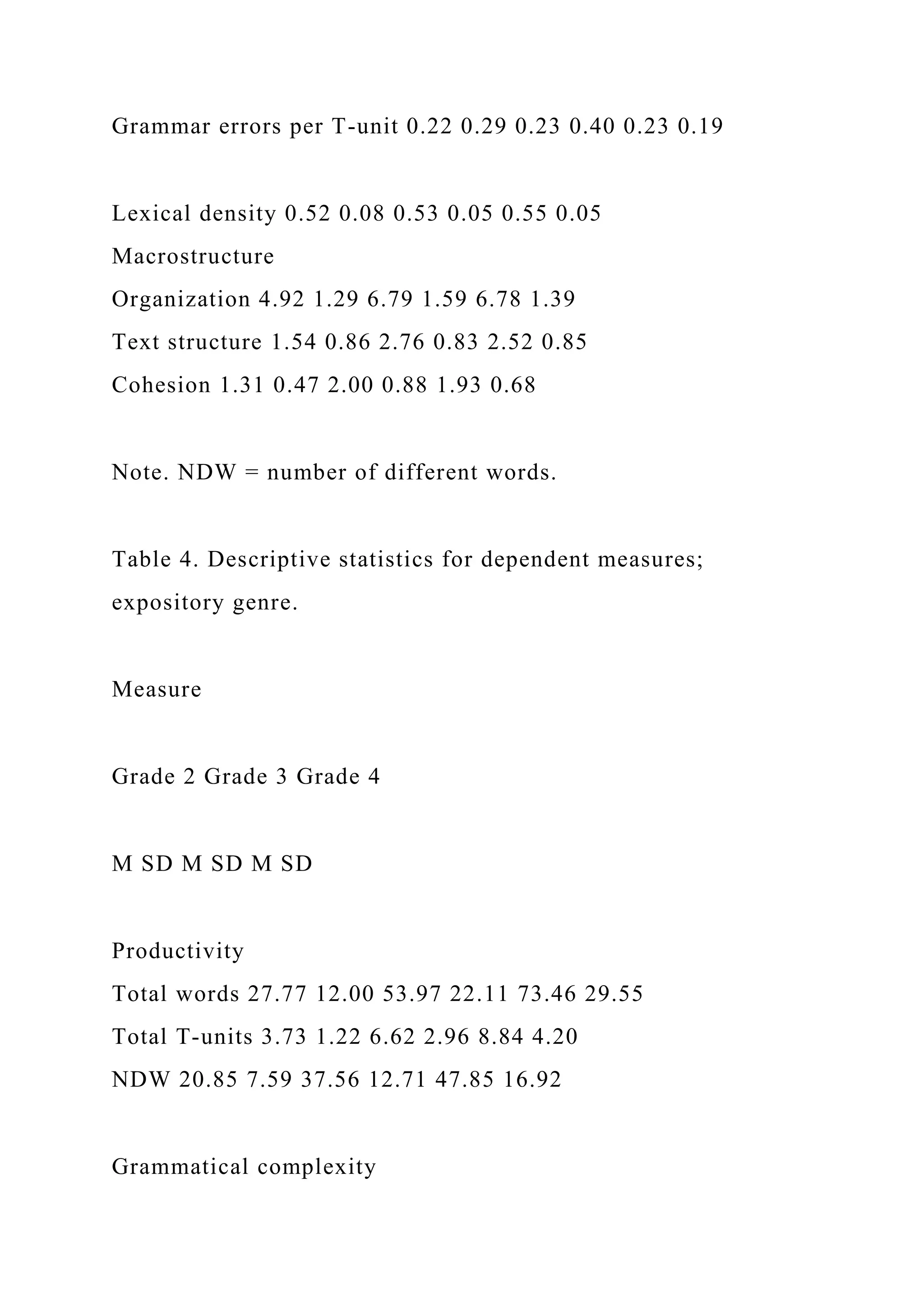

The document discusses the influence of politics on the healthcare system in the US, highlighting significant reforms from the 1930s to contemporary policies such as the Affordable Care Act. It explores how political agendas and competition have shaped healthcare legislation, affecting financing, insurance, delivery, and quality sectors. The analysis suggests that politicians often exploit healthcare gaps for electoral gains while noting the evolving nature of healthcare reforms against the backdrop of political strategies.

![i. Developing Health Maintenance Organizations

D. Jimmy carter

a. Supported national health insurance program

E. Clinton

a. He made changes in health insurance coverage

b. Introduced National Health Reform

F. Harris Wofford

a. He formed democratic debates

b. He insisted on health insurance

G. Barrack Obama

a. Introduced the Affordable Care Act

1. The purpose is creating more tax revenue

2. Condemning citizens to vote for their health care services

V. Introduction of the managed care plan

A. A way of containing health care costs

· [INCLUDE FINDINGS, ANALYSIS, DISCUSSION

SECTIONS HERE]Comment by James A Love: After you give a

solid review, you will need some additional sections to add in

your “new” contributions to the existing literature. Basically,

try to find some meaning from all of the research your studied

to support your thesis. This is typically in the “findings”

section. You may need to revise your thesis if research

indicates something else. That is okay. It is part of iteration

process of making your paper better. Then, a separate

“discussion” section, will include your interpretation of the

findings.

These sections are the important contributions that make this

paper more than simply a review paper. You can choose to

make the paper a “literature review” paper, but you will need to

have many citations and still synthesize some meaning from the

review in a “findings” and “discussion” sections.

VI. ConclusionComment by James A Love: The conclusion will

end up being a summary of what all you did in the previous](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-3-2048.jpg)

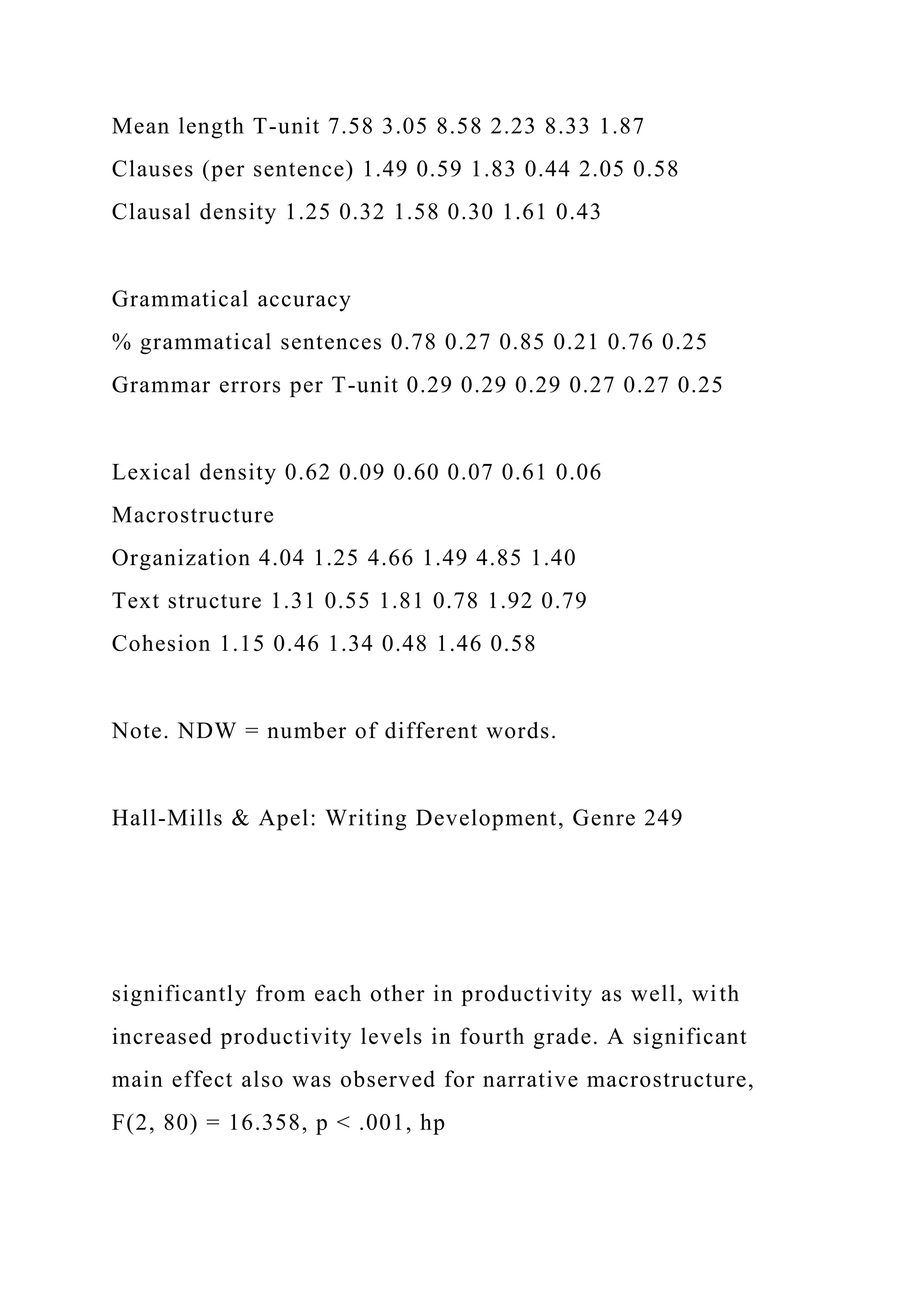

![current practices in writing assessment. Multiple

suggestions are offered for clinical and educational

implications, and specific directions are provided for future

research.

S

peech-language pathologists (SLPs) working with

school-age children and adolescents have important

roles in prevention, identification, assessment, and

intervention for problems involving oral and written lan-

guage (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association

[ASHA], 2010). The school context is heavily influenced by

the established curricular standards, and SLPs contribute

their knowledge of language development to support stu-

dents who struggle with the prerequisite language skills to

achieve those standards. A majority of states have adopted

the Common Core State Standards (Common Core State

Standards Initiative, 2010), which include many rigorous

and integrated written language competencies across grade

levels and content areas. Given their specialized knowledge

base in the normal development of writing in the context

of the general education curriculum (ASHA, 2002), SLPs

can inform the assessment, instruction, and intervention of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-18-2048.jpg)

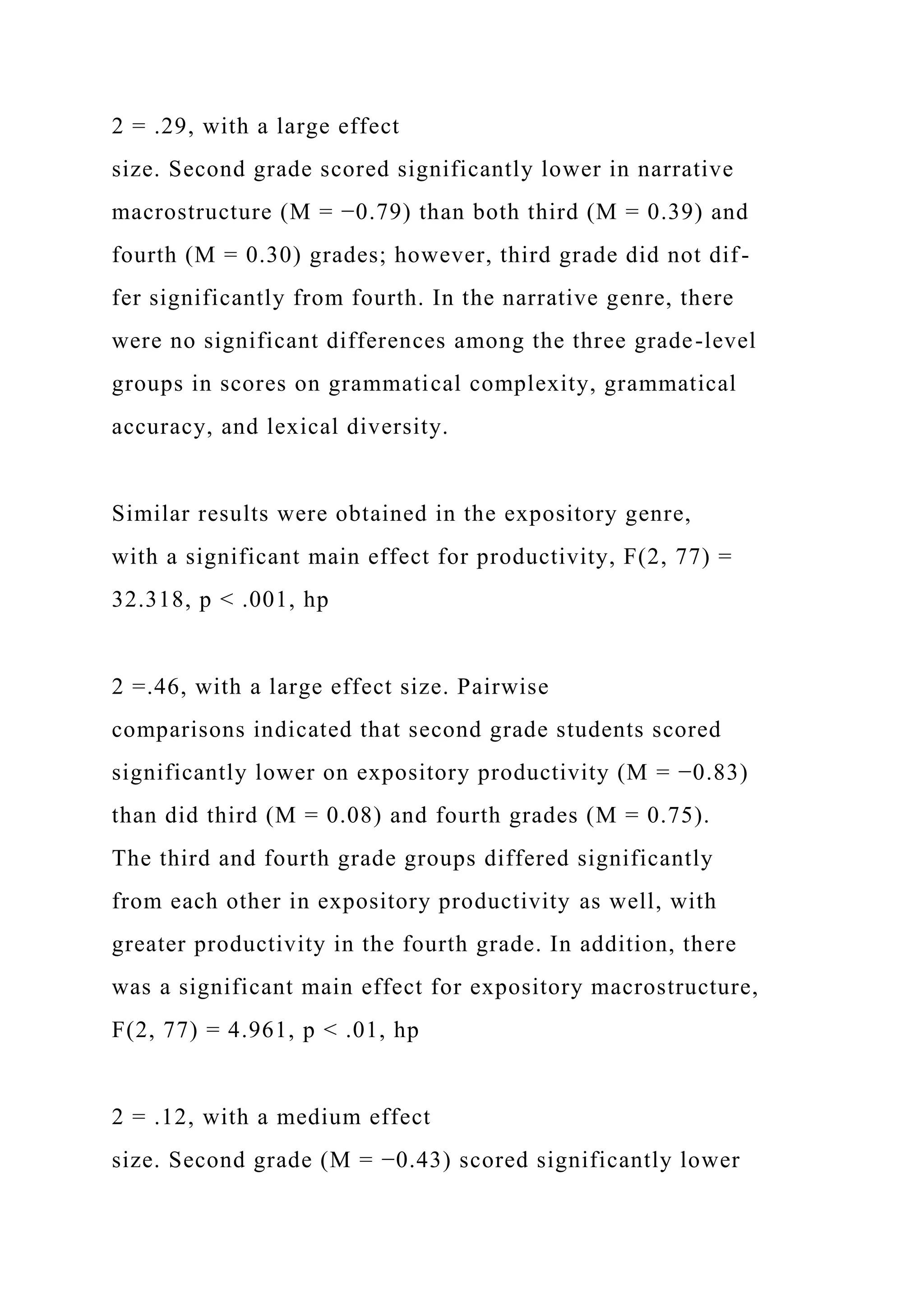

![aFlorida State University, Tallahassee

Correspondence to Shannon Hall-Mills: [email protected]

Kenn Apel is now at the University of South Carolina,

Columbia.

Editor: Marilyn Nippold

Associate Editor: Lynne Hewitt

Received April 5, 2014

Revision received August 21, 2014

Accepted April 6, 2015

DOI: 10.1044/2015_LSHSS-14-0043

Disclosure: The authors have declared that no competing

interests existed at the time

of publication.

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools • Vol. 46 •

242–255 • July 2015 • Copyright © 2015 American Speech-

Language-Hearing Association242

utilize this approach to eliciting student writing. In the basic](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-20-2048.jpg)

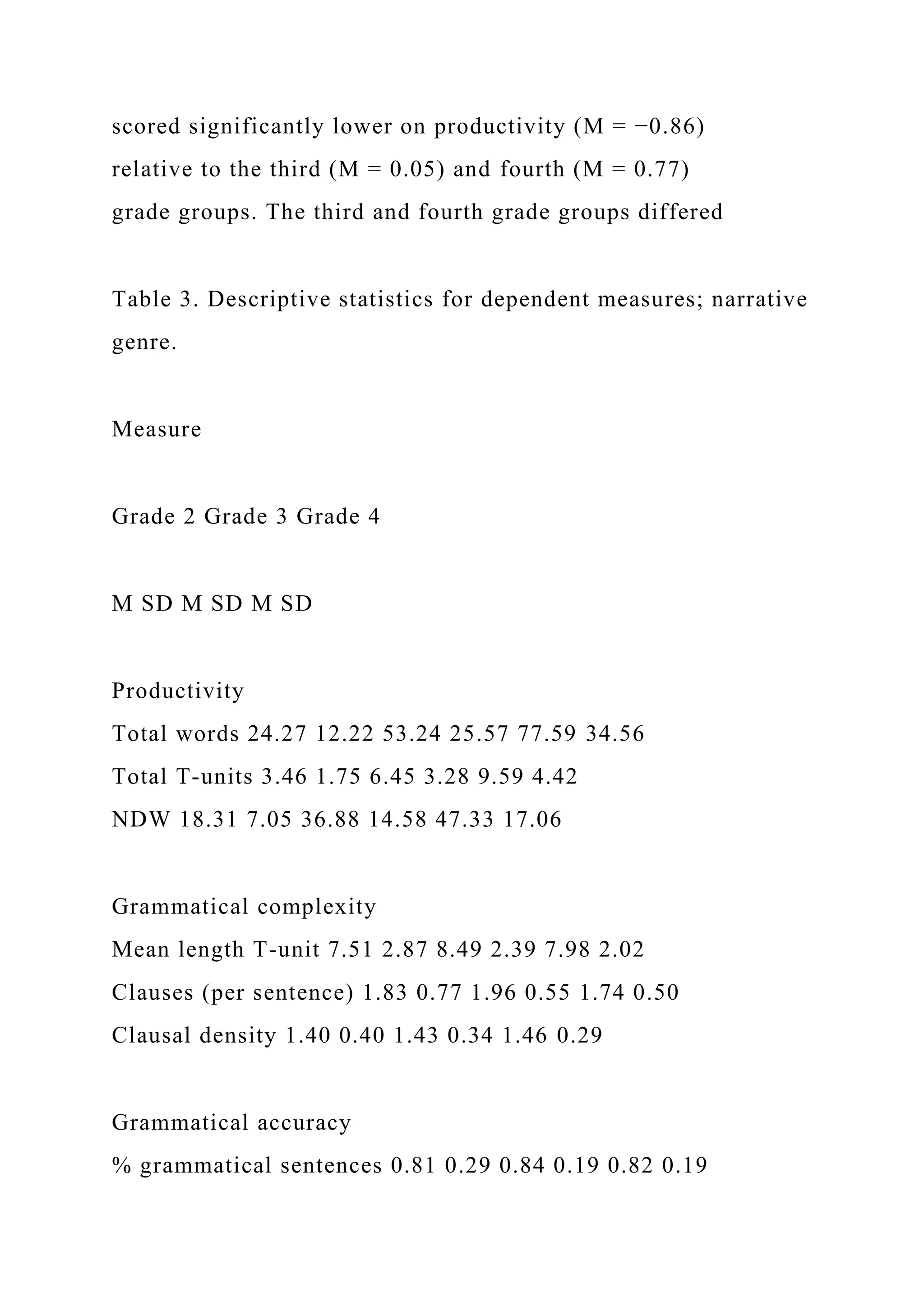

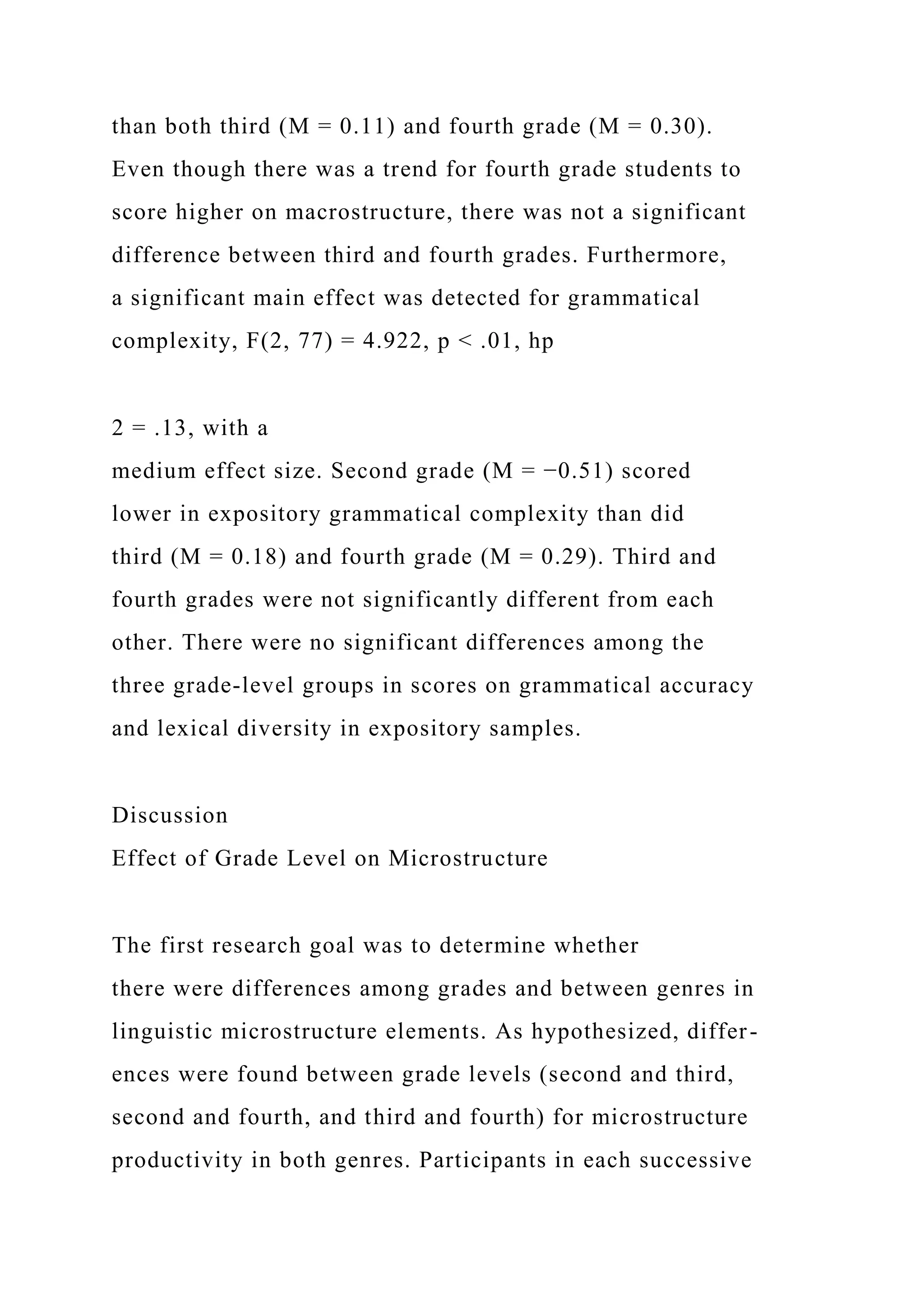

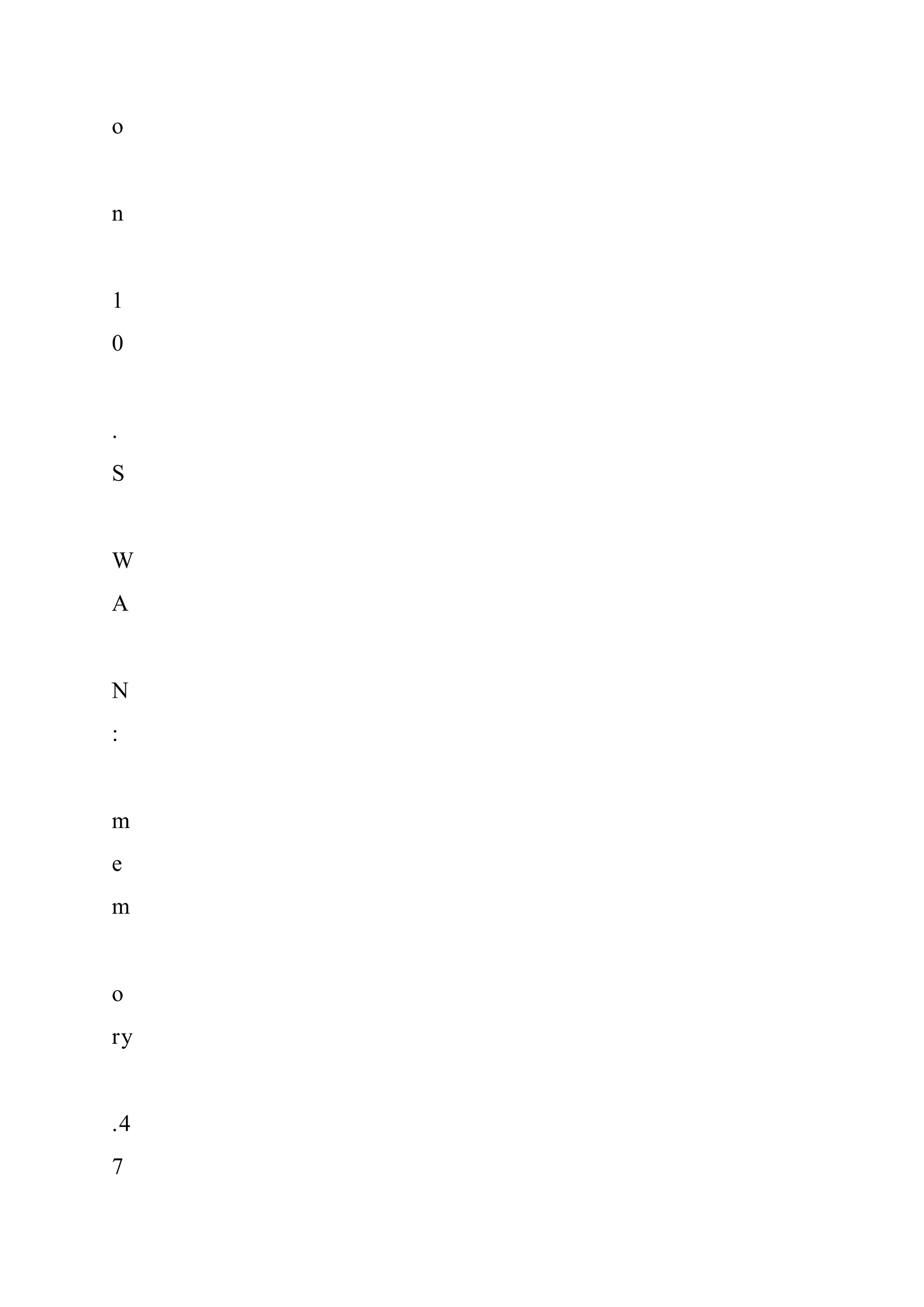

![In summary, analysis of elements of microstructure

in a written product can occur at the word, sentence, and

discourse levels. Microstructure analysis generally includes

measures of productivity (e.g., number of words, T-units, or

ideas), grammatical complexity (e.g., MLTU, clausal den-

sity [CD]), and lexical diversity (e.g., TTR, NDW; Nelson

et al., 2004; Puranik, Lombardino, & Altmann, 2007, 2008).

Taken together, the results of previous investigations sug-

gest that measures of productivity, grammatical complexity,

and lexical diversity are sensitive to age and grade-level dif-

ferences. However, less is known specifically about chil-

dren’s development of certain microstructure elements (e.g.,

productivity, grammatical complexity, lexical diversity) in

early grades (second through fourth), particularly across

genres (e.g., narrative, expository).

Macrostructure

In contrast to microstructure analysis, macrostructure

analysis occurs mainly at the discourse level (Scott, 2009).

Macrostructure is the “abstract representation of the global

meaning structure” which represents the “gist” of the text

(Sanders & Schilperood, 2006, p. 387). Macrostructure

analysis examines a writer’s expression of meaning at the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-27-2048.jpg)

![Sentence Comprehension, and Passage Comprehension

subtests were administered, and standard scores were cal-

culated. According to the test manual (Williams, 2001),

the GRADE has an internal consistency of .95 to .99

(coefficient alpha [a]), and test–retest reliability of .89 to .98.

Receptive Vocabulary Task

The PPVT-4 was administered to determine partici-

pants’ receptive vocabulary levels and to corroborate teacher

report of receptive language skills within typical limits. The

test manual indicates that the PPVT-4 has an internal consis-

tency (split-half reliability) of .94 and test–retest reliability of

.92 to .96 (M = .93).

Writing Tasks

Each participant produced one narrative and one ex-

pository writing sample (15 min each). Writing samples

were elicited during group sessions by the first author and

by trained research assistants. Prompts were selected in

accordance with parallel forms of the state-mandated writ-

ing assessment system protocol (Florida Comprehensive

Assessment Test [FCAT]; Florida Department of Educa-

tion, 2010) and the topical interests of the children enrolled](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-37-2048.jpg)

![Rehabilitative Services (H8435D030046), awarded to the first

author, and a Florida State University Dissertation Research

Grant, also awarded to the first author.

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2002).

Knowl-

edge and skills needed by speech-language pathologists with

respect to reading and writing in children and adolescents

[Knowledge and skills]. Available from www.asha.org/policy

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2010). Roles

and responsibilities of speech-language pathologists in schools

[Professional issues statement]. Available from www.asha.org/

policy

Beers, S. F., & Nagy, W. E. (2011). Writing development in

four

genres from grades three to seven: Syntactic complexity and

genre differentiation. Reading and Writing, 24, 183–202.

doi:10.1007s/11145-010-9264-9

Berman, R. A., & Verhoeven, L. (2002). Cross-linguistic

perspec-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-75-2048.jpg)

![through

multivariate techniques. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Williams, G. J., Larkin, R. F., & Blaggan, S. (2013). Written

language skills in children with specific language impairment.

International Journal of Language and Communication

Disorders,

48(20), 160–171. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12010

Williams, K. T. (2001). Group Reading Assessment and

Diagnostic

Exam (GRADE). Circle Pines, MN: AGS.

Williams, K. T. (2001). Group Reading Assessment and

Diagnostic

Exam—Technical Manual. Circle Pines, MN: AGS.

Appendix

Narrative and Expository Writing Samples

Second Grade Narrative

Once my sister Lily scared me by hiding on the walls when I

was in the restroom[3CL][CC].

When I came out she went “ROAR”![2CL][CC].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-85-2048.jpg)

![It was scary.

and I screamed[2CL][CC].

Then I started to laugh so hard I fell on the ground[2CL][CC].

Third Grade Narrative

One day a man went to McDonald’s to get something to eat

through the drive through[3CL][CC].

When he got his lunch the bag started to shake[2CL][CC].

The hamburger popped out.

and the french fries popped out.

and they grow[GE] and grow[GE] until they became

humongous[4CL][CI].

They took over the world[1CL][SC].

But in a matter of time they shrunk.

and the man had his lunch[2CL][CC].

Fourth Grade Narrative

When I got surprised it was when my cousin told me she broke

her wrist[4CL][CC].

it really happened yesterday[1CL][SC].

she was playing soccer and running backwards and tripped on

grass.

and her hand caught her and broke[5CL][CC].

she is[GE] getting a light green cast[1CL][SI].

Judith wished she broke her other hand.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-86-2048.jpg)

![so she didn’t have to write[3CL][CC].

But she broke her left hand[1CL][SC].

Second Grade Expository

I am a superhero.

and I have super powers[2CL][CC].

My power is to turn into lava[1CL][SC].

I can also turn invisible[1CL][SC].

I can use my powers to help save the world[2CL][CC].

When I see a villain, I turn invisible.

and then I burn them up like they are on a grill[4CL][CC].

That is how I save the world[1CL][SC].

Third Grade Expository

Hi my name is Gardenia[1CL][SC].

I have the powers to make things grow right after I plant the

seeds[3CL][CC]!

I would like to help the Earth by turning landfills into beautiful

gardens[2CL][CC].

That’s all I have to say for today, bye[2CL][CC].

Fourth Grade Expository

I am a superhero named Superman[1CL][SC].

My special powers are that I am very strong.

and I can beat up everyone.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-87-2048.jpg)

![and I can fly[4CL][CC].

I will help the world by beating up evil villains and arresting

people[3CL][CC].

I will help elderly people cross the road and give money to

banks, homeless shelters, nursing homes, and

orphans[2CL][CC].

That is who I am and how I will help the world[2CL][CC].

Note. CC = complex correct sentence; CL = clause for number

of clauses; SC = simple correct sentence; SI = simple incorrect

sentence.

Hall-Mills & Apel: Writing Development, Genre 255

Copyright of Language, Speech & Hearing Services in Schools

is the property of American

Speech-Language-Hearing Association and its content may not

be copied or emailed to

multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright

holder's express written permission.

However, users may print, download, or email articles for

individual use.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-88-2048.jpg)

![2010 Levy Avenue, Suite 100, Tallahassee, FL 32310, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

Y. Petscher

Florida Center for Reading Research, Florida State University,

2010 Levy Avenue, Suite 100,

Tallahassee, FL 32310, USA

S. Al Otaiba

Simmons School of Education and Human Development,

Southern Methodist University, University

Park, TX, USA

123

Read Writ (2014) 27:1163–1188

DOI 10.1007/s11145-013-9480-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-92-2048.jpg)

![(e.g., ‘‘I eat and play [STOP] and go outside and laugh [STOP]

and draw pictures.’’

counted as three sentences). For calculating the number of ideas

in a student’s

writing sample, only ideas that could be identified in the

writing were counted, Ideas

required a subject and a predicate, but could use a common

subject/verb (e.g., ‘‘I

like playing’’ would be scored as one idea; ‘‘I like playing and

writing’’ would count

as two ideas). Repeated ideas were only counted once. These

scoring measures for

writing fluency (i.e., production) have been utilized in previous

studies with students

in the earliest grades (Kim et al., 2011, in press).

In the spring of first grade, students were asked to compose a

brief narrative text](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-130-2048.jpg)

![each observed variable

1172 S. Kent et al.

123

(i.e., [1 - reliability] 9 r2). Multiple indices were evaluated to

assess model fit

including Chi square, root mean square error of approximation

(RMSEA),

comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and

standardized root

mean square residuals (SRMR). Given that Chi square values

tend to be influenced

by sample size, RMSEA values below .085, CFI/TLI values

greater than .95, and

SRMR below .05 indicate excellent model fit (Kline, 2011).

To account for the non-independence of observations, cluster-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-139-2048.jpg)

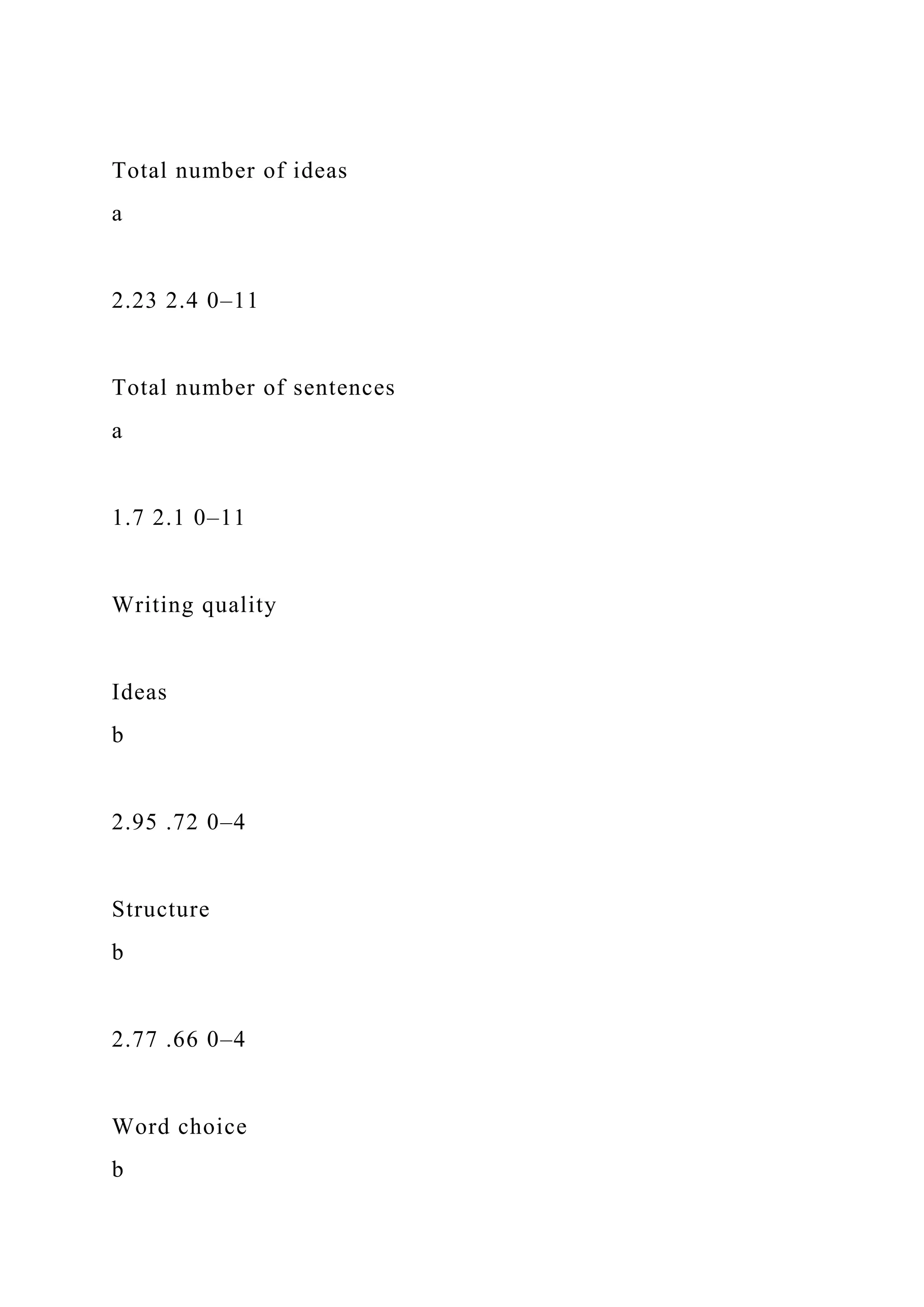

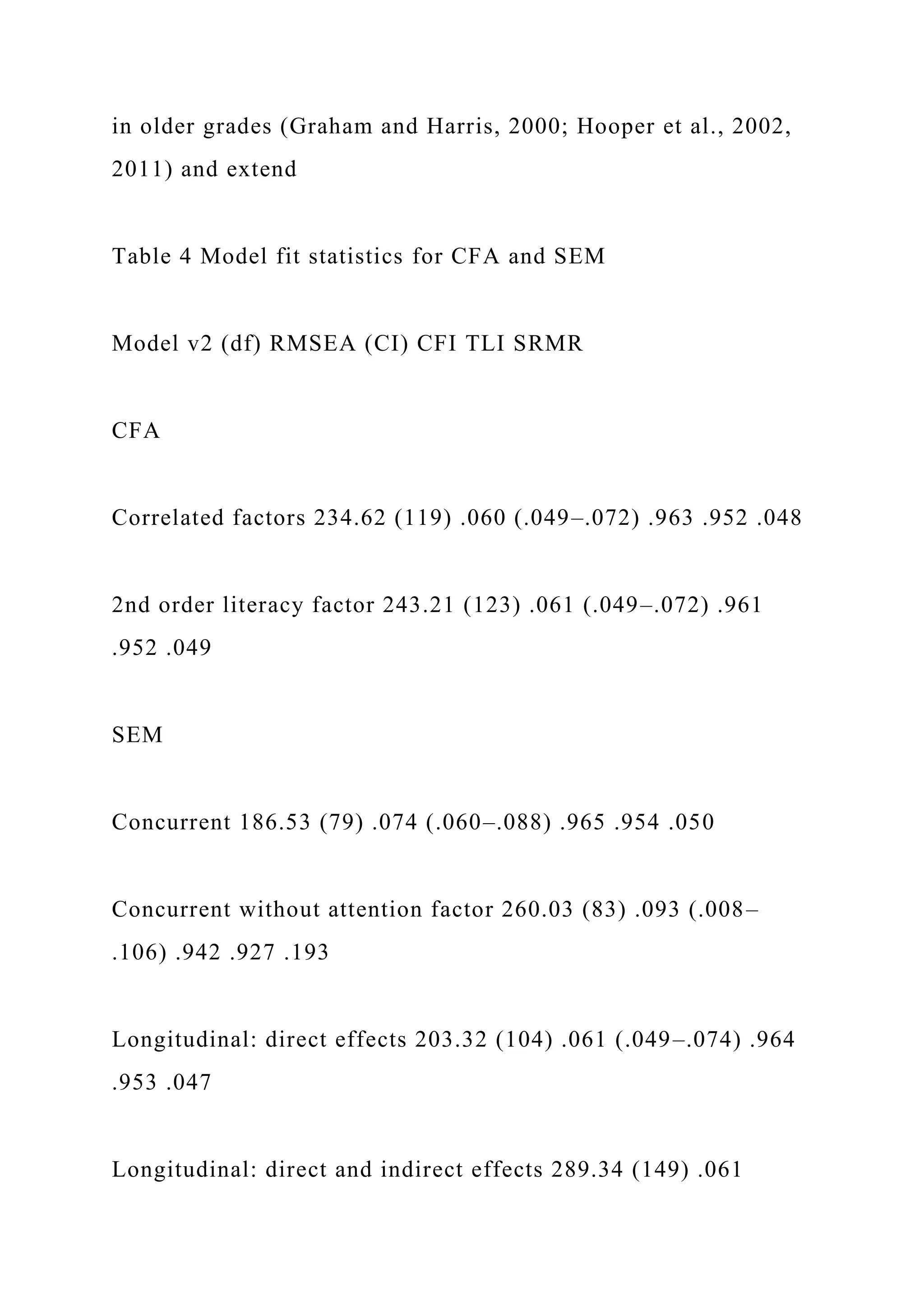

![variables, all of which were statistically significant (p .01).

Measurement model

Initial evaluation of the fit indices for the proposed

measurement model indicated

excellent data fit: v2 (119) = 234.62, p = .000; CFI = .963; TLI

= .952;

RMSEA = .060 (CI [.049, .072]); and SRMR = .048. All

predictor factors were

significantly and positively related to one another (.33 B r B

.95) and with writing

in kindergarten and first grade, with generally moderate

correlations (see Table 3).

Predictors of kindergarten and first grade writing 1173

123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-143-2048.jpg)

![For this reason, CFA was used to examine whether an

alternative model with a

second-order ‘‘literacy’’ might better explain the data than the

existing correlated

factors model. The alternative model also demonstrated good fit

[v2 (123) = 243.21,

p = .000; CFI = .961; TLI = .952; RMSEA = .061 (CI [.049,

.072]); and

SRMR = .049]. Results from a Chi square difference test (Dv2 =

8.84, df = 4,

p = .065) suggest this more parsimonious model would be

preferred and thus, was

used in subsequent analyses.

1

Figure 1 displays factor loadings for each latent factor.

Research questions 1 and 2

The first research question addressed the unique and shared](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-210-2048.jpg)

![relations of component

skills of writing fluency in kindergarten. Standardized

parameter estimates and

standard errors for the hypothesized SEM of writing production

in kindergarten, are

presented in Fig. 2a. Results suggested good model fit: v2 (79)

= 186.53, p = .000;

CFI = .965; TLI = .954; RMSEA = .076 (CI [.062, .090]); and

SRMR = .050.

Literacy (i.e., reading and spelling), letter-writing fluency, oral

language, and

attention were all positively related to one another (u range =

.35-.57, ps .01).

Attention-related skills (c = .16, p = .001) exhibited a unique

and statistically

significant relation to kindergarten composition fluency after

controlling for

literacy, handwriting fluency, and oral language. Early literacy

skill in reading](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-211-2048.jpg)

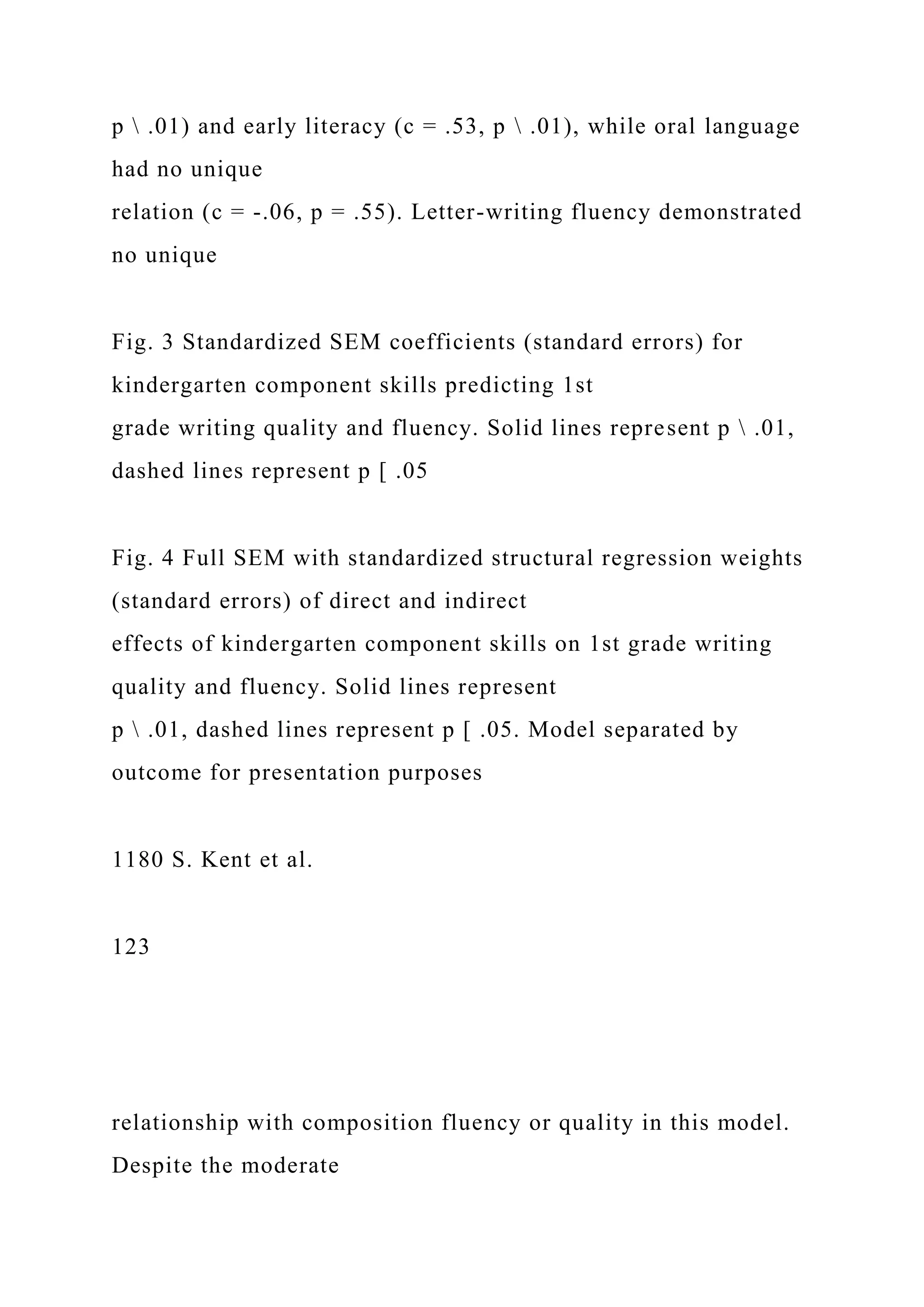

![(Fig. 2b). The model including attention had a statistically

significant better fit than

a model without this factor (Dv2 = 73.5, df = 4, p .001)

supporting its inclusion.

Research question 3

The third research question considered the longitudinal relations

of kindergarten

component skills to first grade writing. As presented in Fig. 3, a

SEM predicting

compositional fluency and quality in first grade from

kindergarten component skills

exhibited excellent fit: v2 (104) = 203.32, p = .000; CFI = .964;

TLI = .953;

RMSEA = .061 (CI [.049, .074]); and SRMR = .047. In this

longitudinal model,

attention in kindergarten was uniquely related to both

compositional fluency](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-215-2048.jpg)

![quality and fluency respectively, in first grade.

Fig. 1 Factor loadings for kindergarten and first grade latent

variables

1178 S. Kent et al.

123

Research question 4

The final question examined whether kindergarten component

skills had a direct or

indirect effect on first grade writing quality and fluency. The

resulting model (see

Fig. 4) again demonstrated excellent model-data fit: v2 (149) =

289.34, p = .000;

CFI = .962; TLI = .951; RMSEA = .061 (CI [.050, .071]); and

SRMR = .046.

After accounting for both compositional fluency in kindergarten](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-217-2048.jpg)

![and express their ideas of

science through use of writing. Aligned with the research

findings in their theoretical

framework, Prain and Hand concluded that in writing to learn

activities in the area of science,

writing should include five critical elements. These elements

include writing objectives,

writing types, the audience, subject matter containing concept

clusters and method of text

production (Hand & Prain, 2002). Critical combination of those

elements can yield

Corresponding Author email: [email protected] ©

ISSN:1304-6020

TÜRK FEN EĞİTİMİ DERGİSİ

Yıl 7, Sayı 4, Aralık 2010](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-272-2048.jpg)

![Journal of

TURKISH SCIENCE EDUCATION

Volume 7, Issue 4, December 2010

http://www.tused.org

mailto:[email protected]

Atila, Günel & Büyükkasap / TUSED / 7(4) 2010 129

meaningful science learning. Further, they argued that language

especially writing has an

essential role in doing science as well as learning science.

Norris and Phillips (2003) reported that language has two main

roles in science literacy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-273-2048.jpg)

![DOI 10.1007/s11881-011-0056-y

S. R. Hooper (*)

Departments of Psychiatry, Psychology, Pediatrics, and

Education,

The Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities,

CB#7255,

University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill,

NC 27599-7255, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

L.-J. C. Costa : A. Childress: S. B. Knuth

School of Education, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill,

Chapel Hill, NC, USA

M. McBee

Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of

North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Chapel

Hill, NC, USA

K. L. Anderson: D. C. Yerby

The Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities,

University of North Carolina School of Medicine,

Chapel Hill, NC, USA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-302-2048.jpg)

![consistency~.96), fine-motor speed and control (PAL-2 Finger

Succession, internal

consistency~.89), language-related functions (Peabody Picture

Vocabulary Test-4/Compre-

hensive Receptive and Expressive Vocabulary Test, internal

consistency~.91 to .94;

Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing [CTOPP]

Elision Subtest, internal

consistency~.89 to .90; PAL-2 Rapid Automatized Naming

Letters/Digits, internal

consistency~.84 to .92; PAL-2 Word Choice, internal

consistency~.66 to .83), and

attention/executive functions (CTOPP Nonword

Repetition/WISC-IV-PI Digit Span,

WISC-IV-PI Spatial Span, internal consistency~.68 to .83; WJ-

III Planning, internal

consistency~.75; Vigil Continuous Performance Test Omissions

and Commissions,

temporal stability~.70). In addition, the WIAT-II Word Reading

Subtest (internal

consistency~.95) was employed as a possible moderator of

response to intervention,

particularly given findings suggesting a relatively strong](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-318-2048.jpg)

![Copyright of Annals of Dyslexia is the property of Springer

Science & Business Media B.V. and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a

listserv without the copyright holder's express

written permission. However, users may print, download, or

email articles for individual use.

Instructional Science28: 199–226, 2000.

© 2000Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

199

Writing and conceptual change. What changes?

LUCIA MASON1 & PIETRO BOSCOLO2

1Department of Pedagogical, Psychological and Didactical

Sciences, University of Lecce,

Via Stampacchia 45, 73100 Lecce, Italy, e-mail:

[email protected];2Department of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-383-2048.jpg)

![Developmental and Socialization Psychology, University of

Padova, Via Venezia 8, 35131

Padova, Italy, e-mail: [email protected]

Received: 30 December 1997; in final form: 7 April 1999;

accepted: 24 June 1999

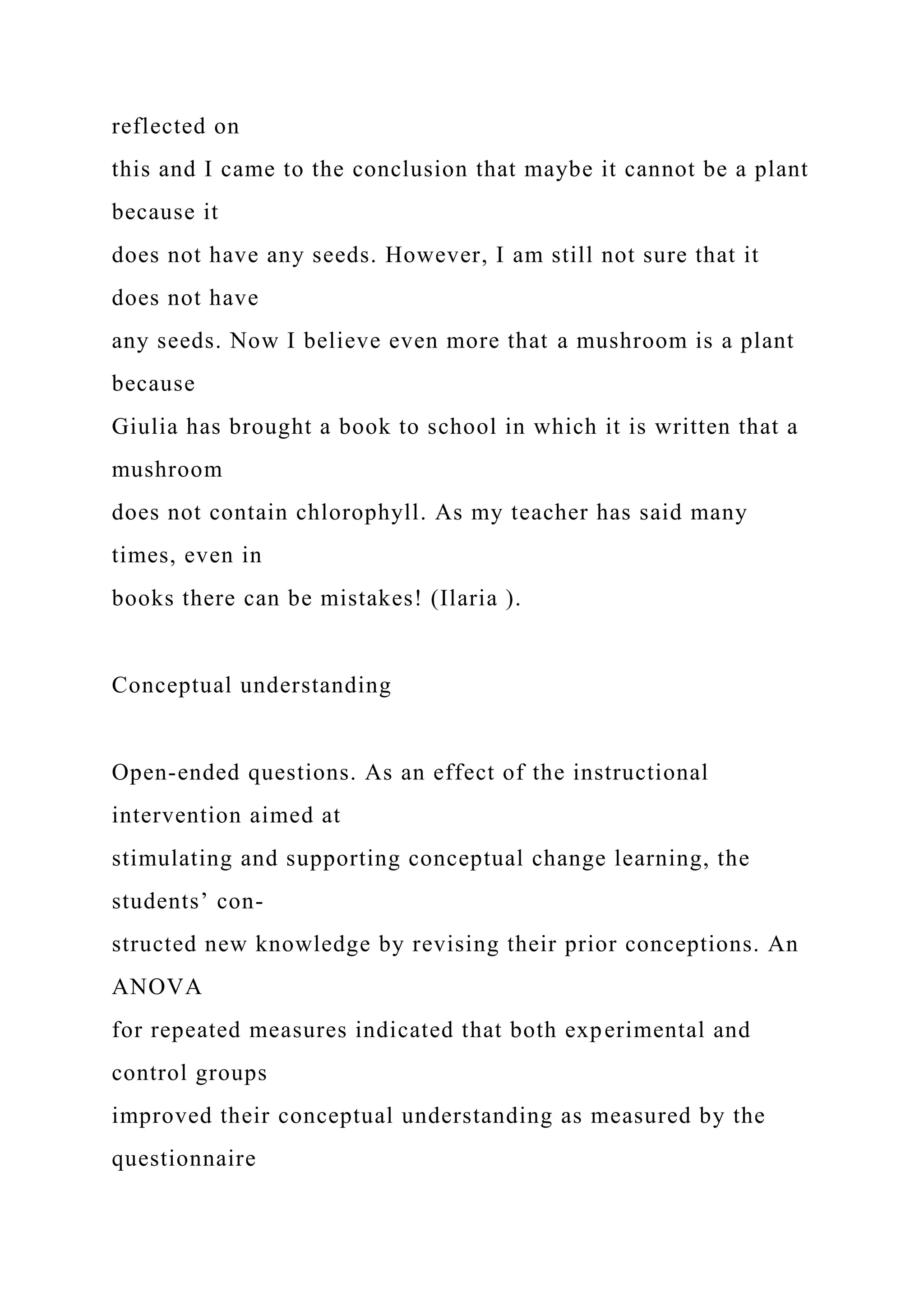

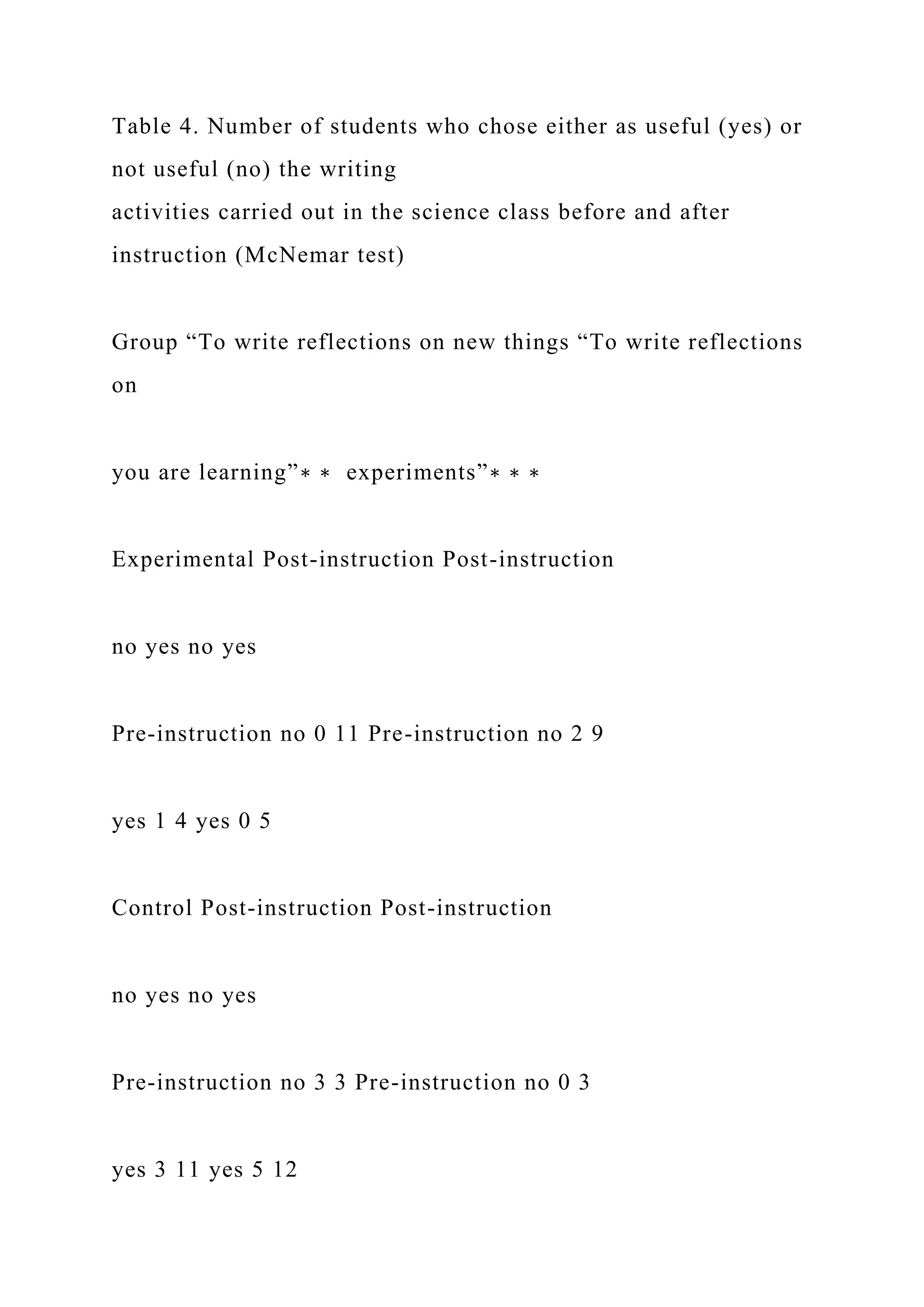

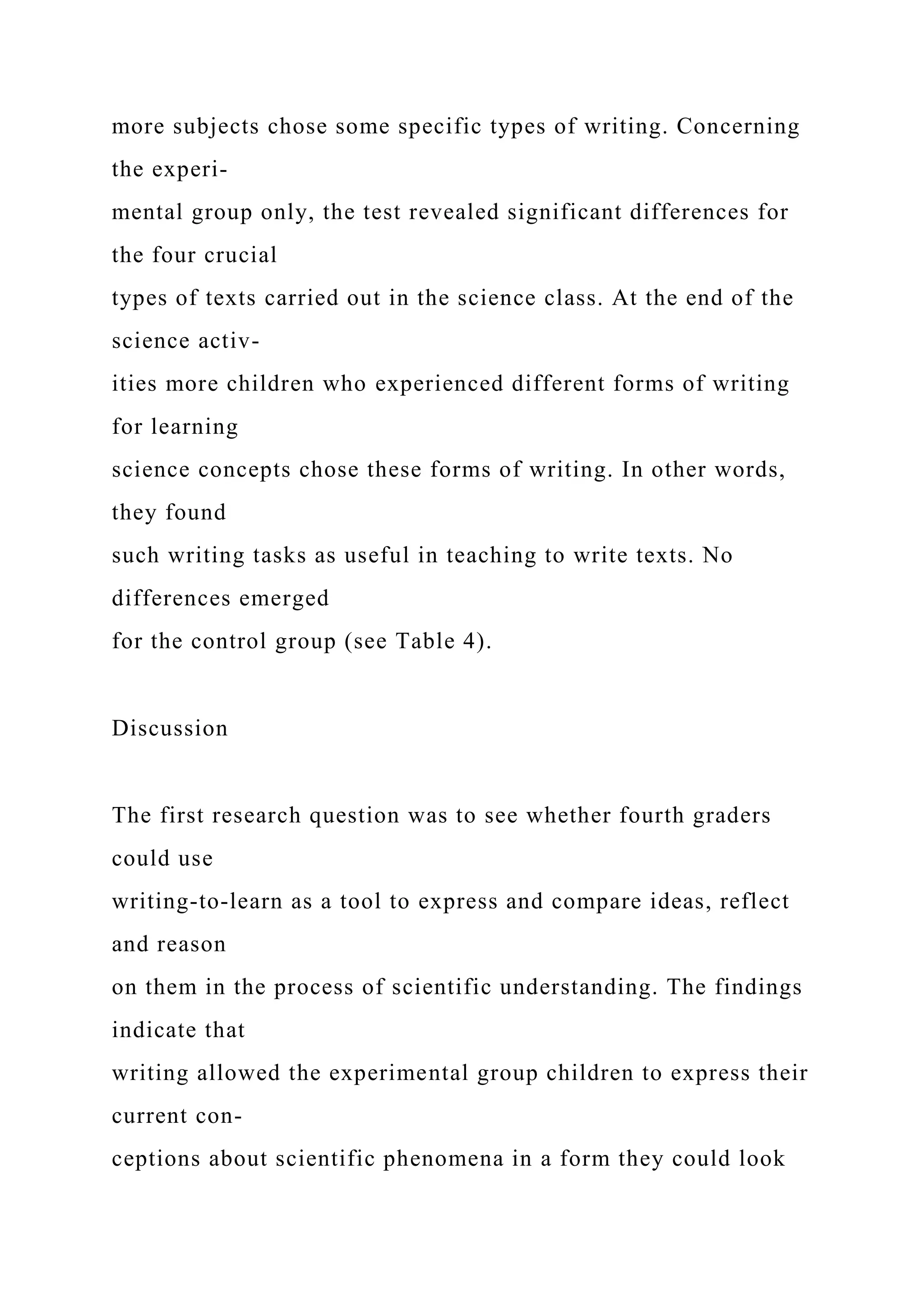

Abstract. This study was focused on elementary school

students’ processes of scientific

understanding within a classroom environment characterized as

a community of discourse.

In particular, it explored the role of written discourse both on

the plane of knowledge devel-

opment and the conceptualization and evaluation of the writing

activity itself. The purposes

of the study were: (a) to see whether students could use writing

as a means to express and

compare ideas, reason and reflect on them in the process of

scientific understanding; (b) to

see whether writing in the service of learning facilitated the

understanding of the new topic

through conceptual change; (c) to see whether writing affected

the conceptualization of the

writing activity itself. Thirty-six fourth graders divided in two

groups, experimental (writing)

and control (no-writing), were involved in the implementation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-384-2048.jpg)

![60(4): 603–624.

Bereiter, C. (1994). Constructivism, socioculturalism, and

Popper’s World 3.Educational

Researcher23(7): 21–23.

Bereiter, C. & Scardamalia, M. (1989). Intentional learning as a

goal of instruction. In L.B.

Resnick, ed.,Knowing, Learning, and Instruction: Essays in

Honor of Robert Glaser,

pp. 361–392. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Boscolo, P. (1995). The cognitive approach to writing and

writing instruction: A contribution

to a critical appraisal.Cahiers de Psycologie Cognitive14(4):

343–366.

Brown, A.L. & Campione, J.C. (1990). Communities of learning

and thinking, or A context by

any other name. In D. Kuhn, ed.,Developmental Perspectives on

Teaching and Learning

Thinking Skills[Special issue].Contribution to Human

Development21: 108–126.

Brown, A.L. & Campione, J.C. (1994). Guided discovery in a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadpoliticsandhealthcasesystemsinuspoliticsand-221111005934-8c790caa/75/Running-Head-POLITICS-AND-HEALTH-CASE-SYSTEMS-IN-USPOLITICS-AND-docx-464-2048.jpg)