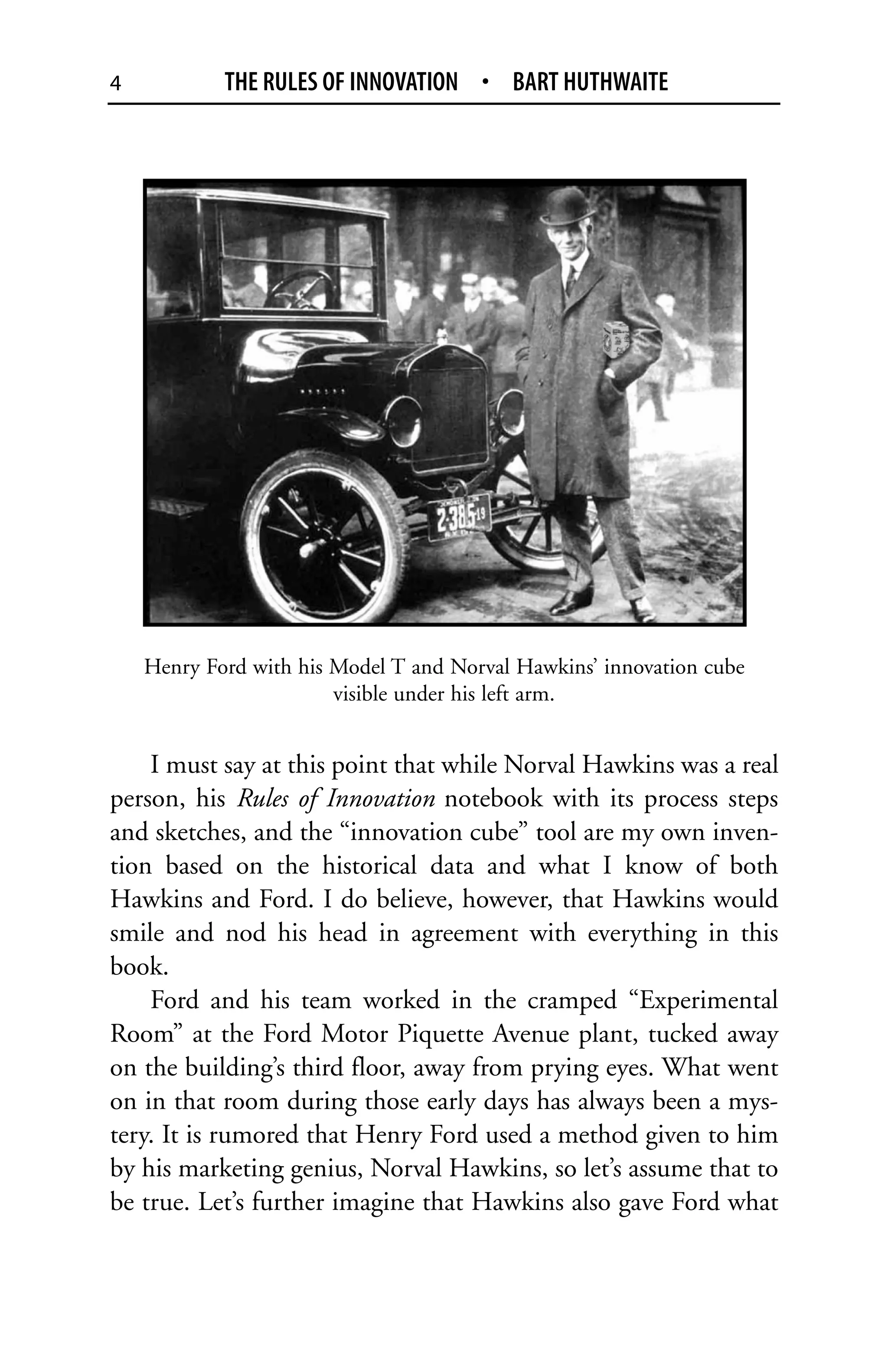

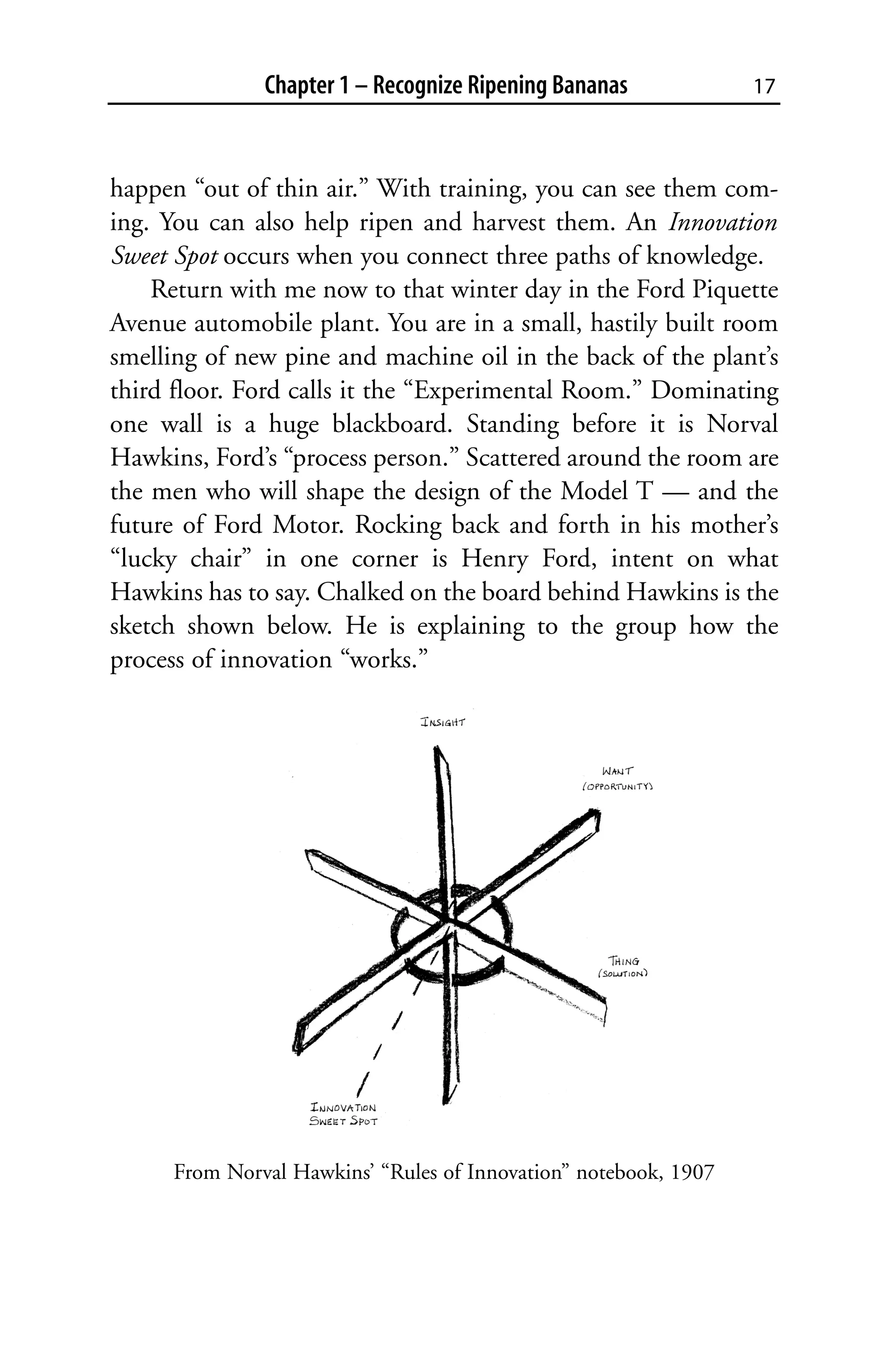

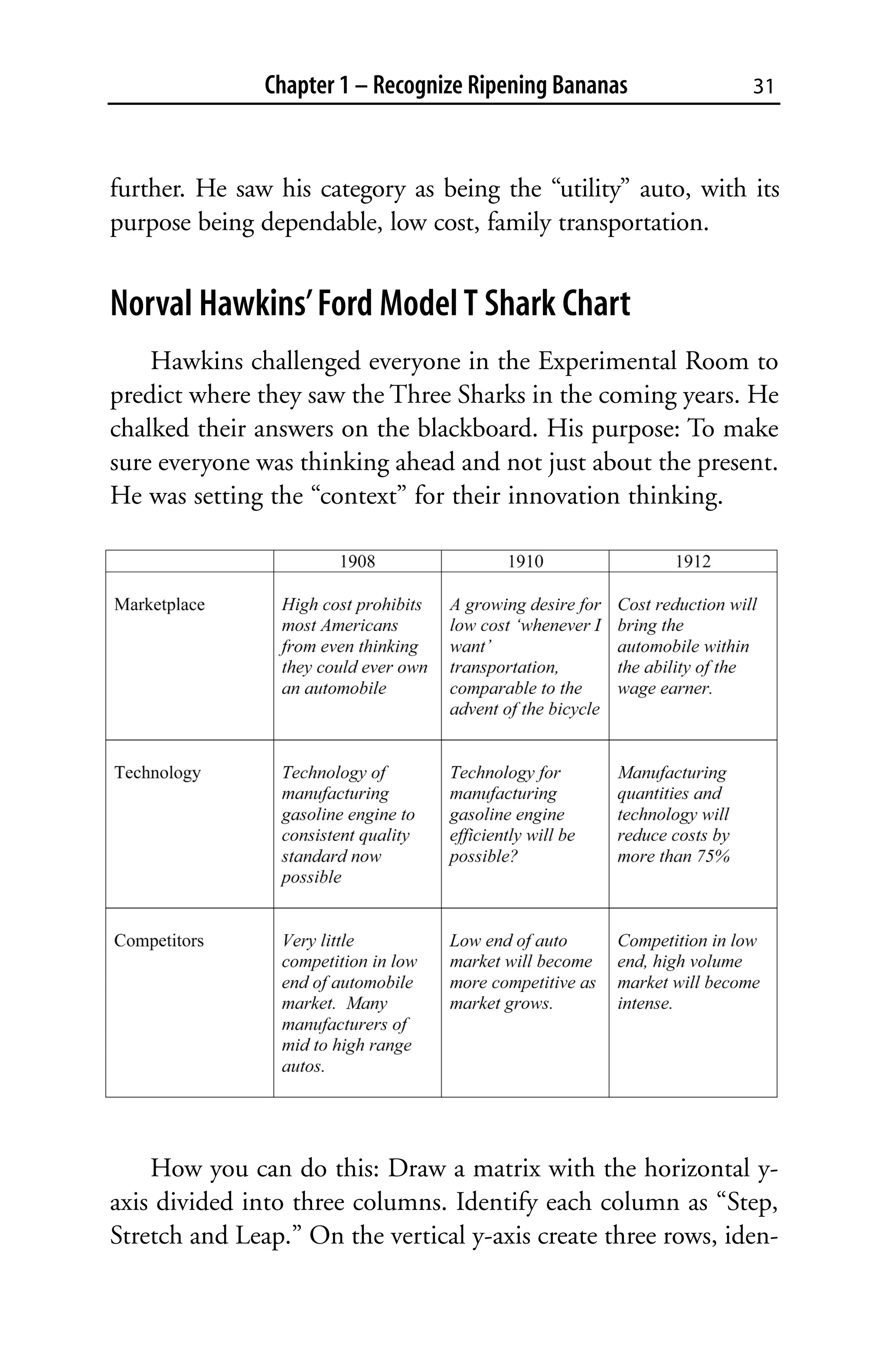

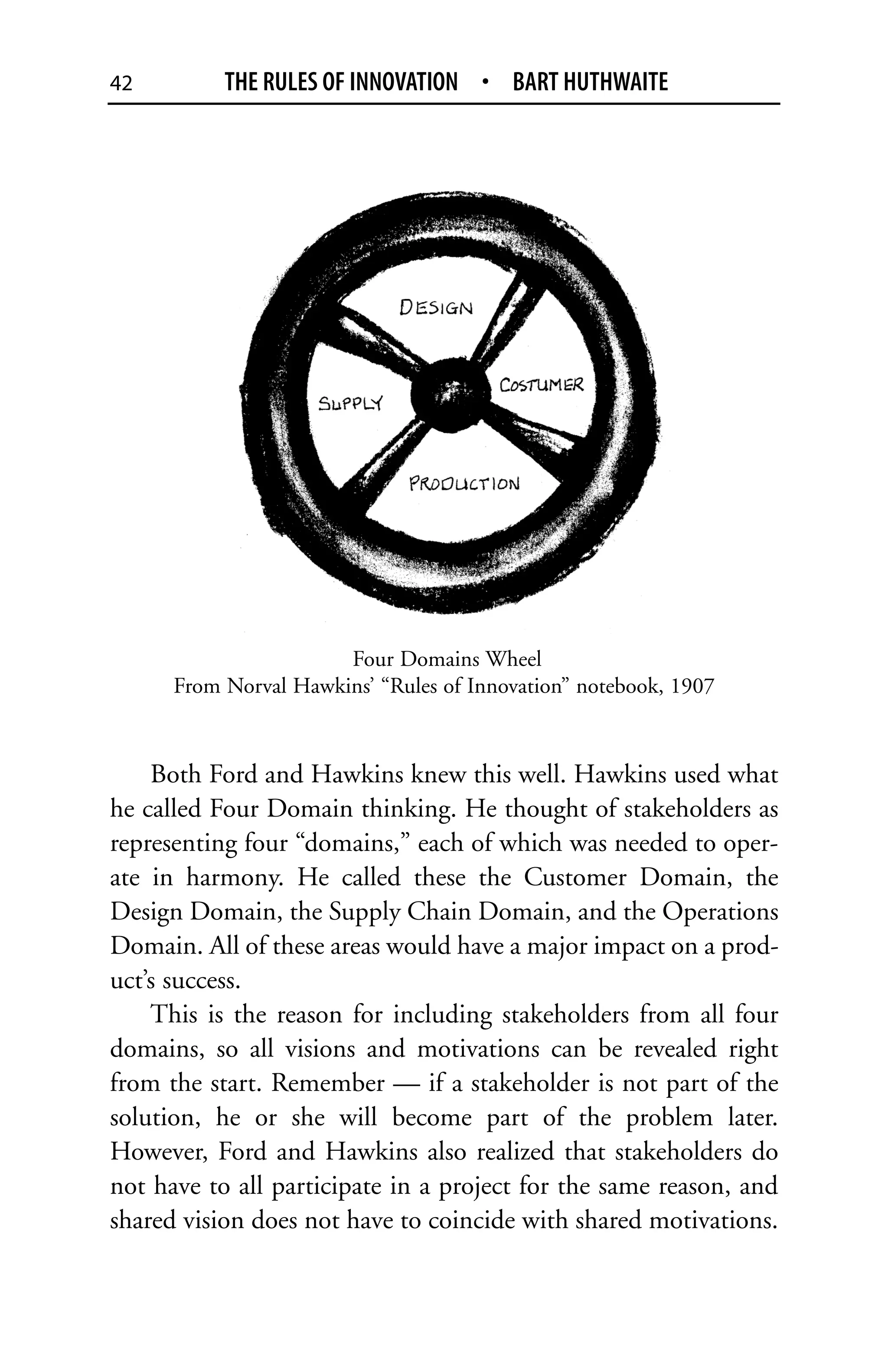

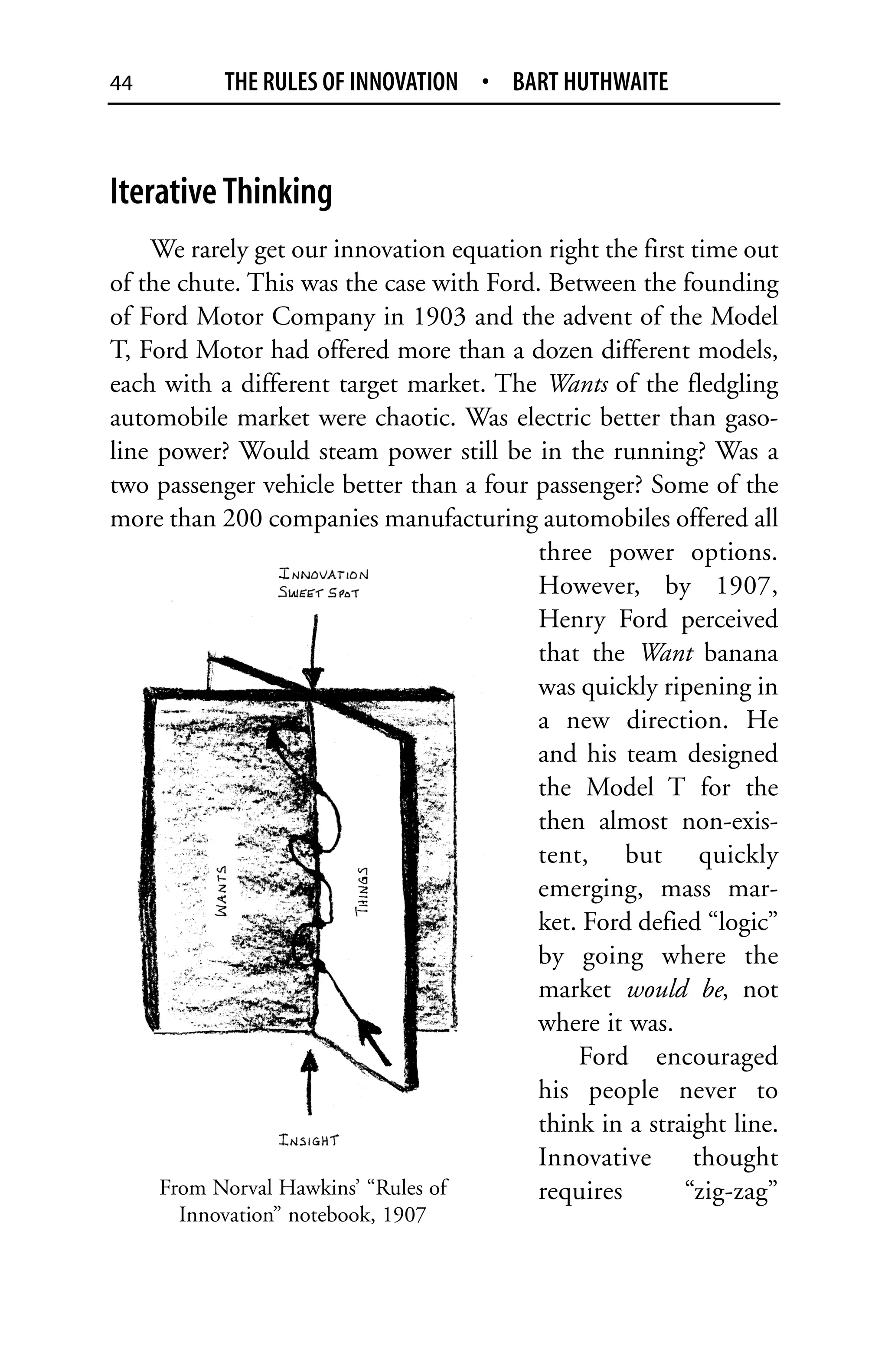

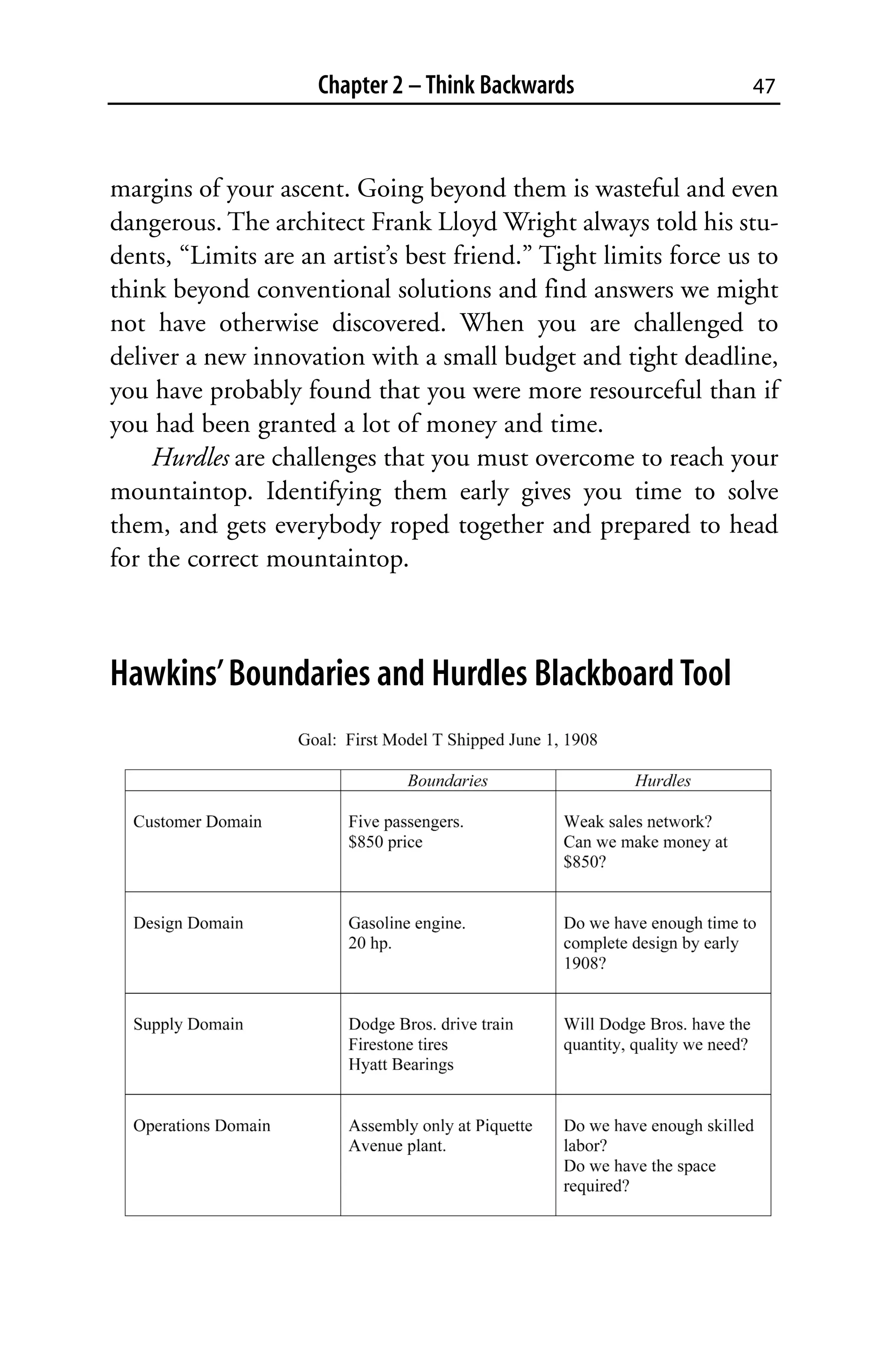

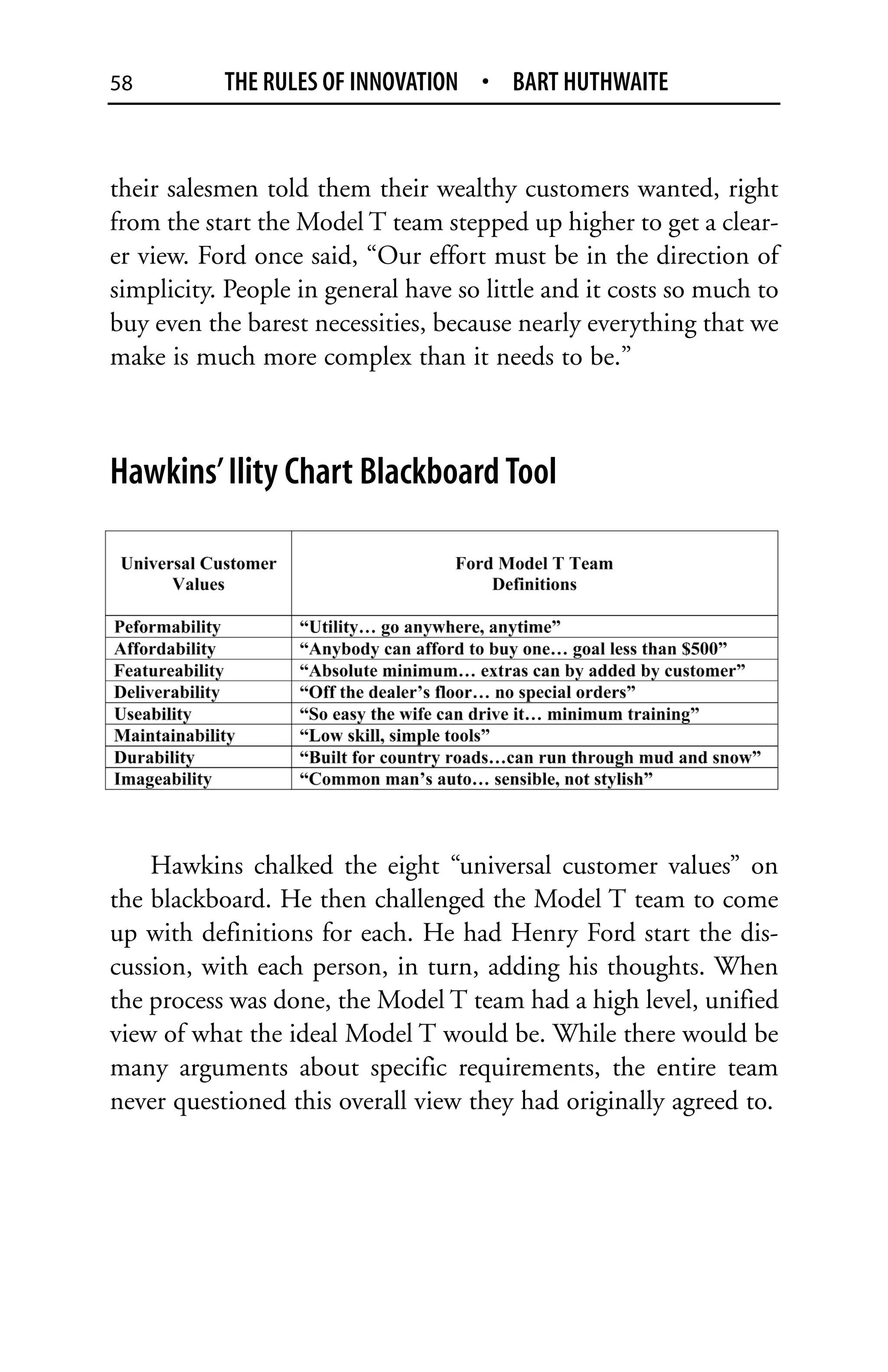

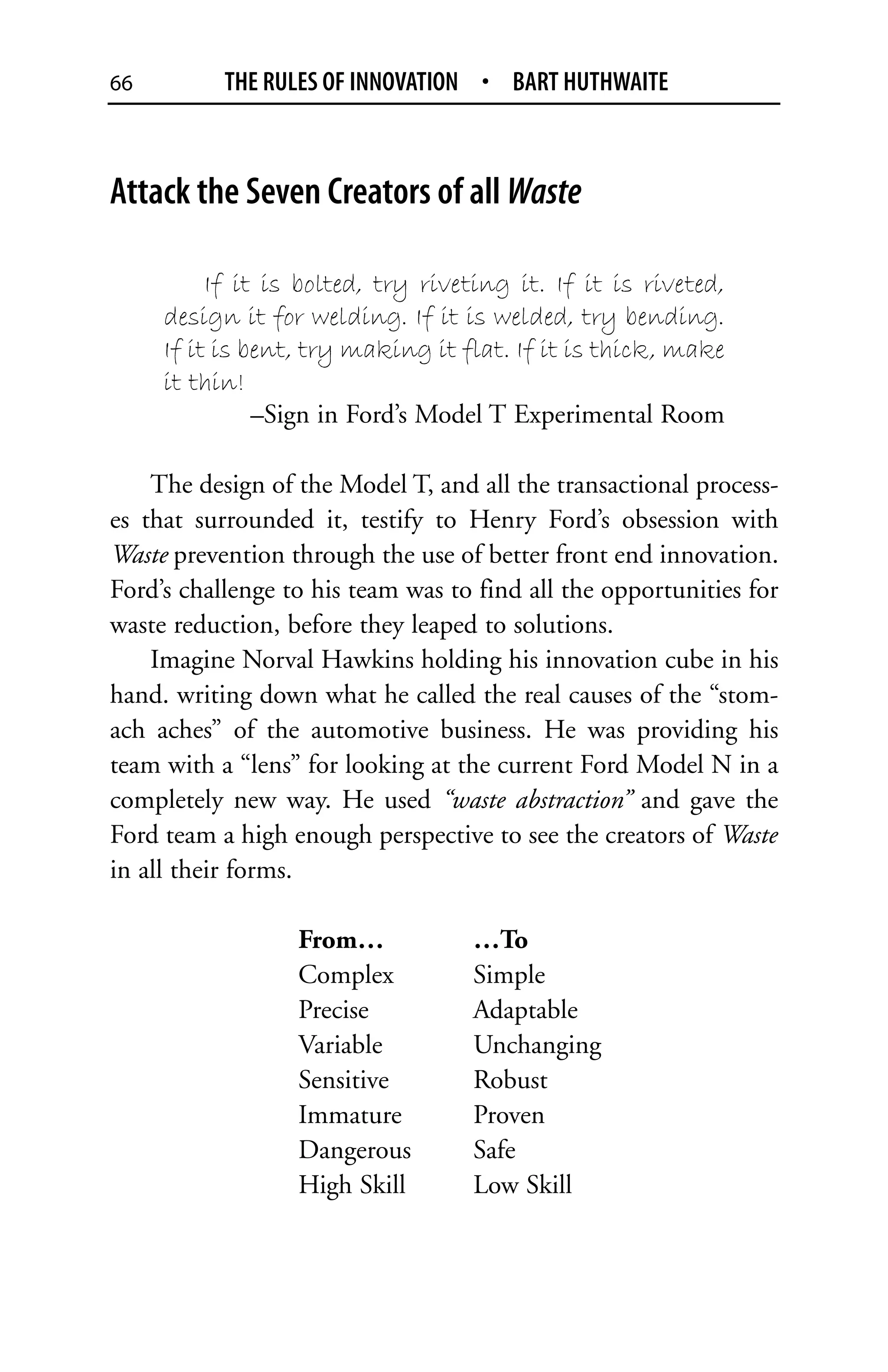

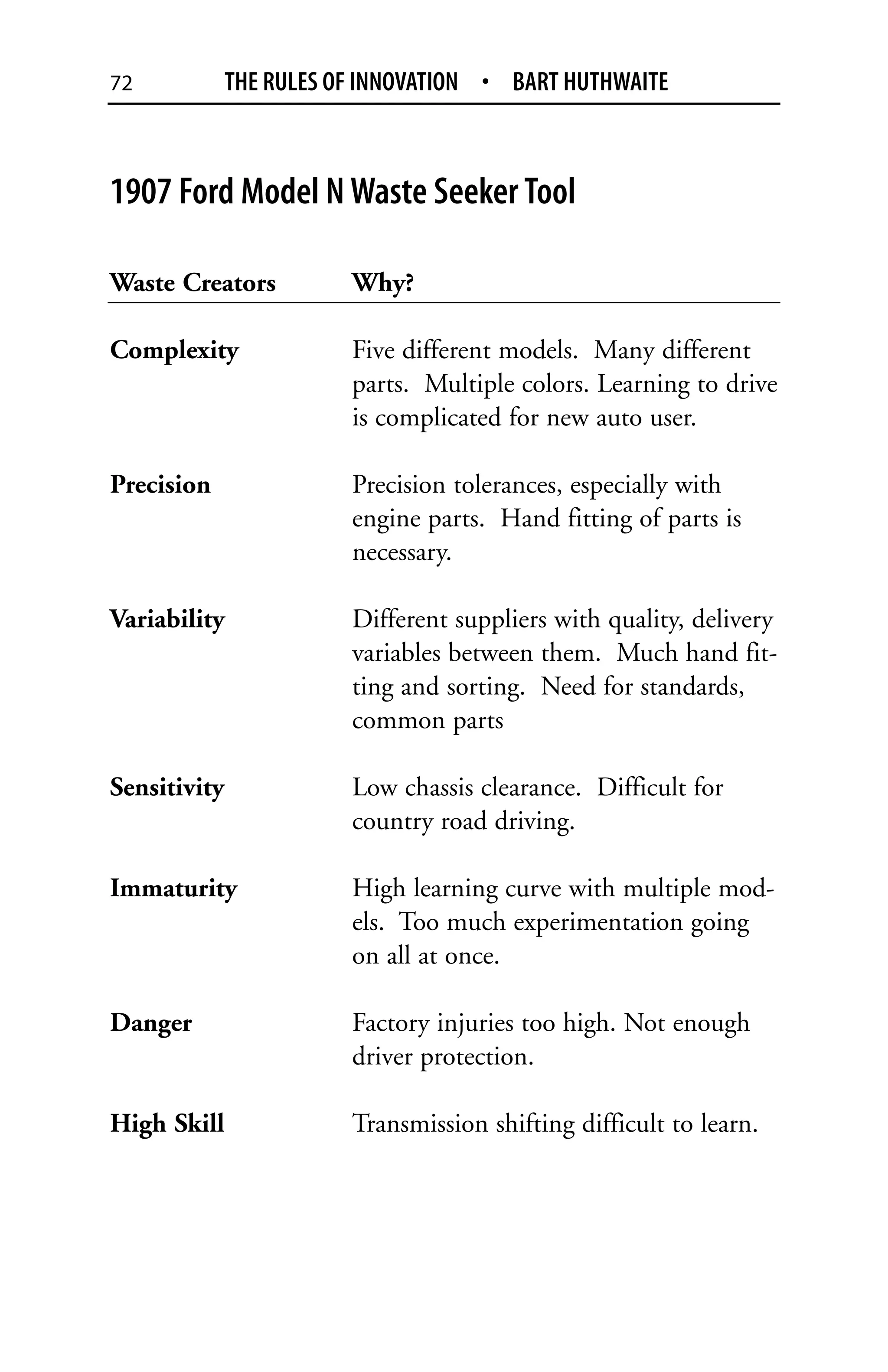

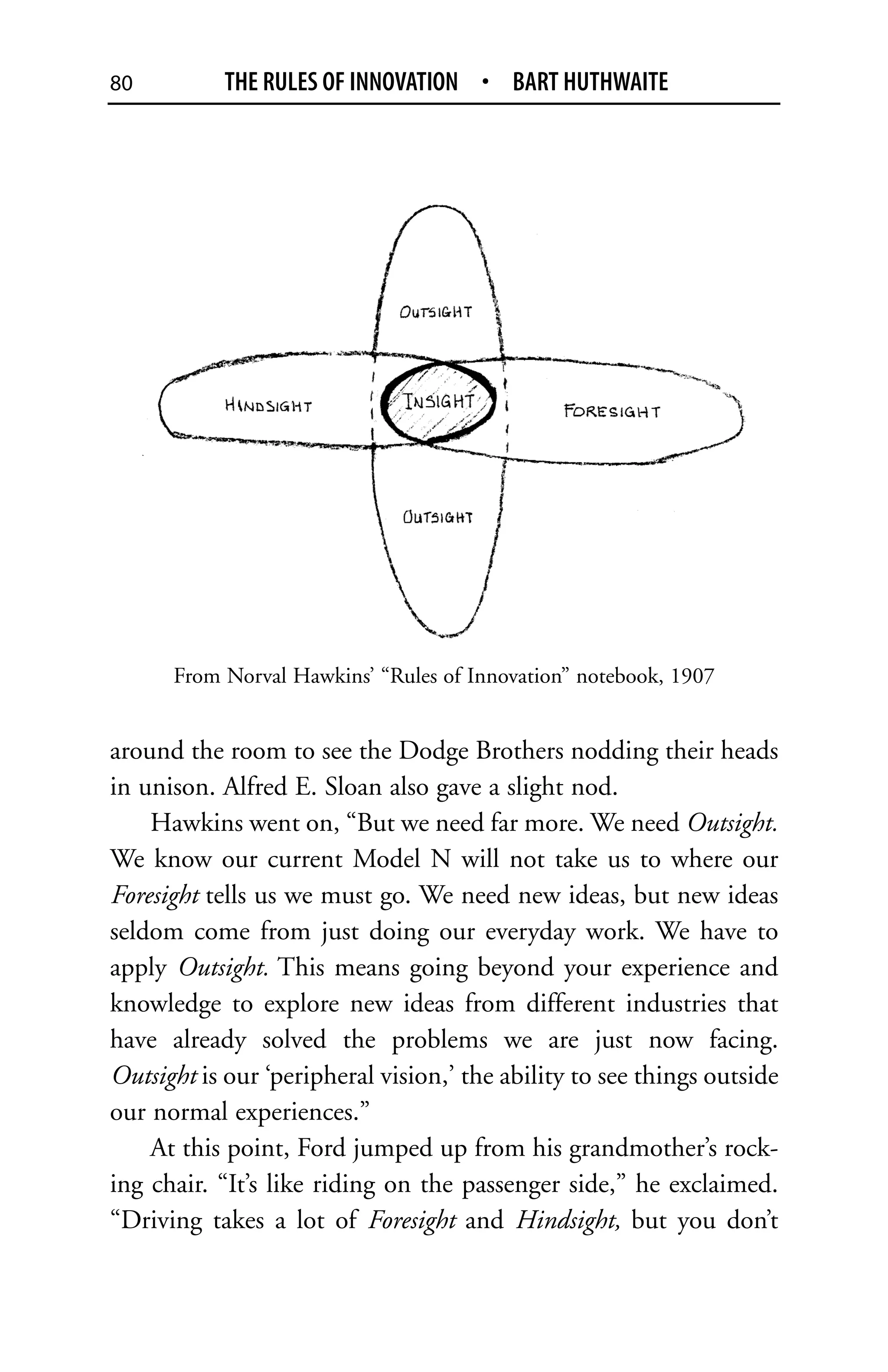

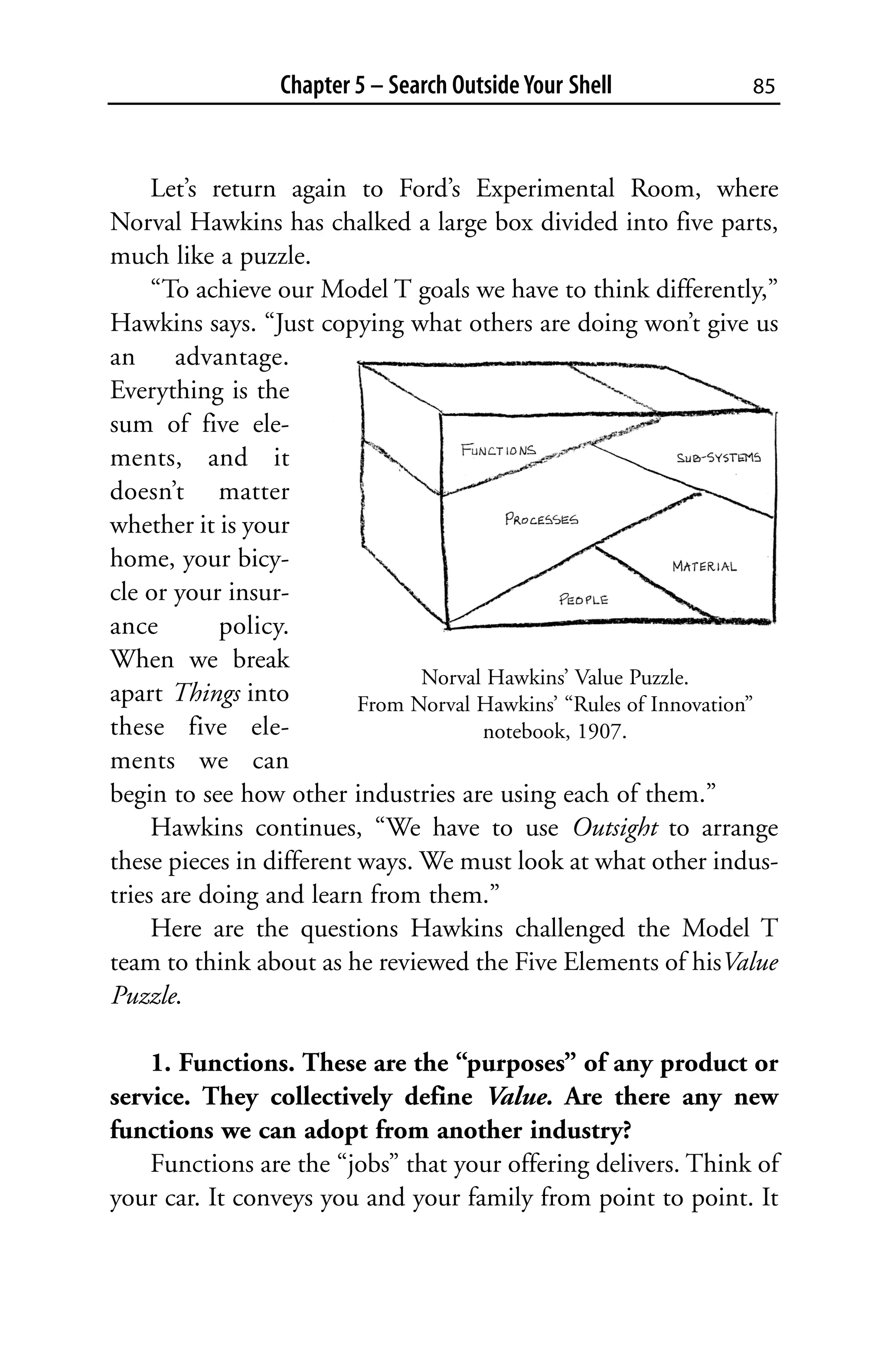

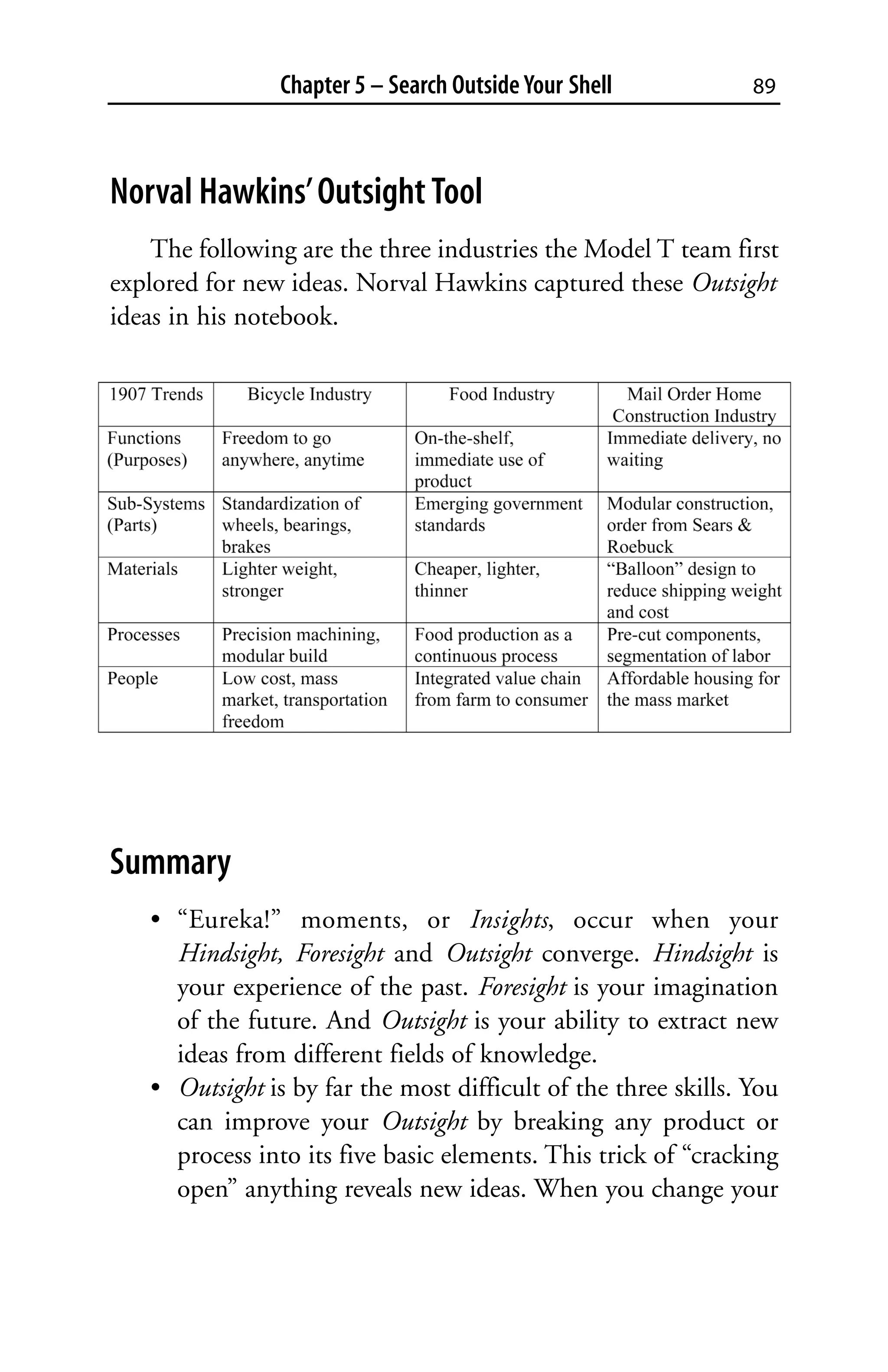

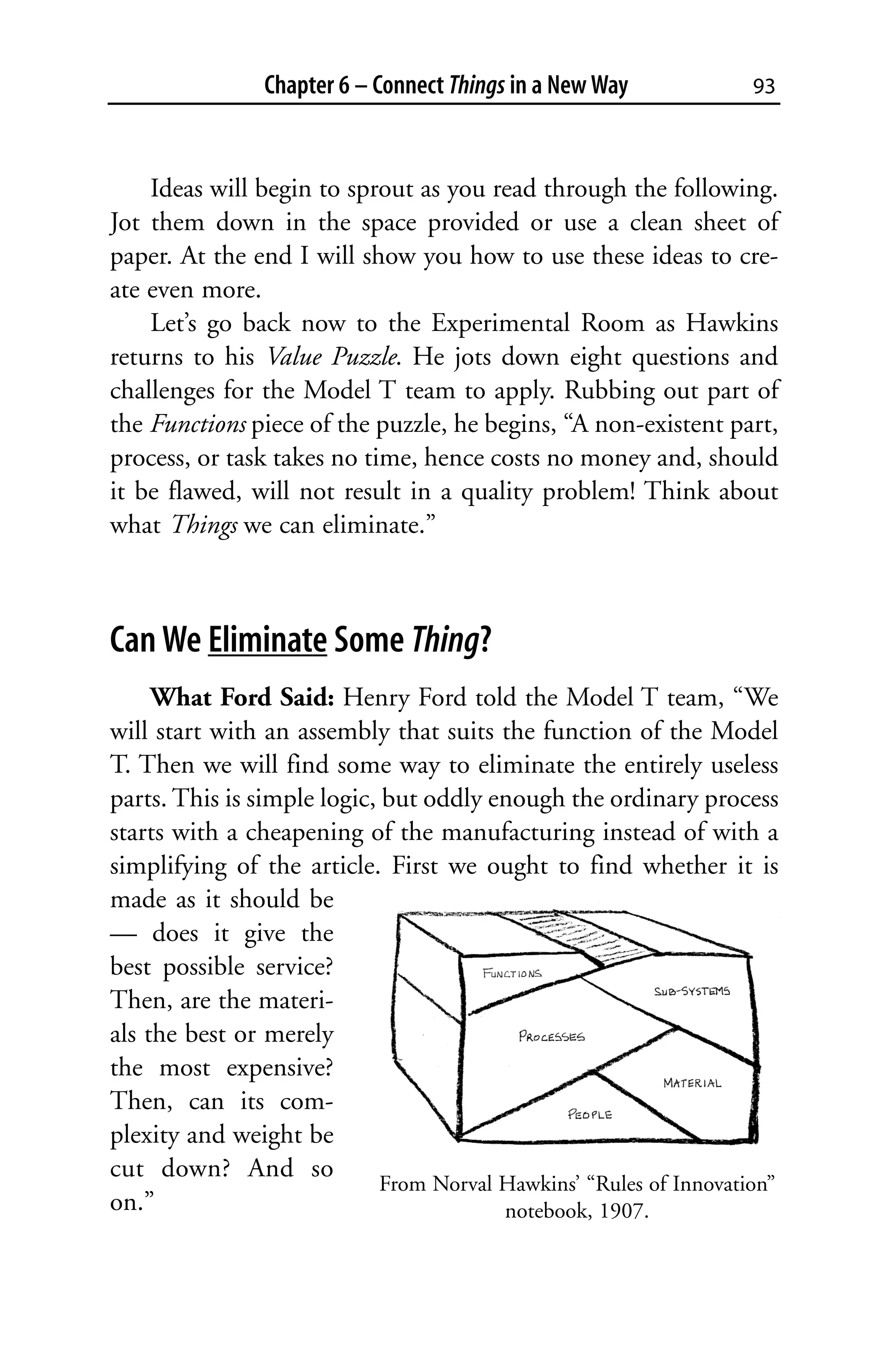

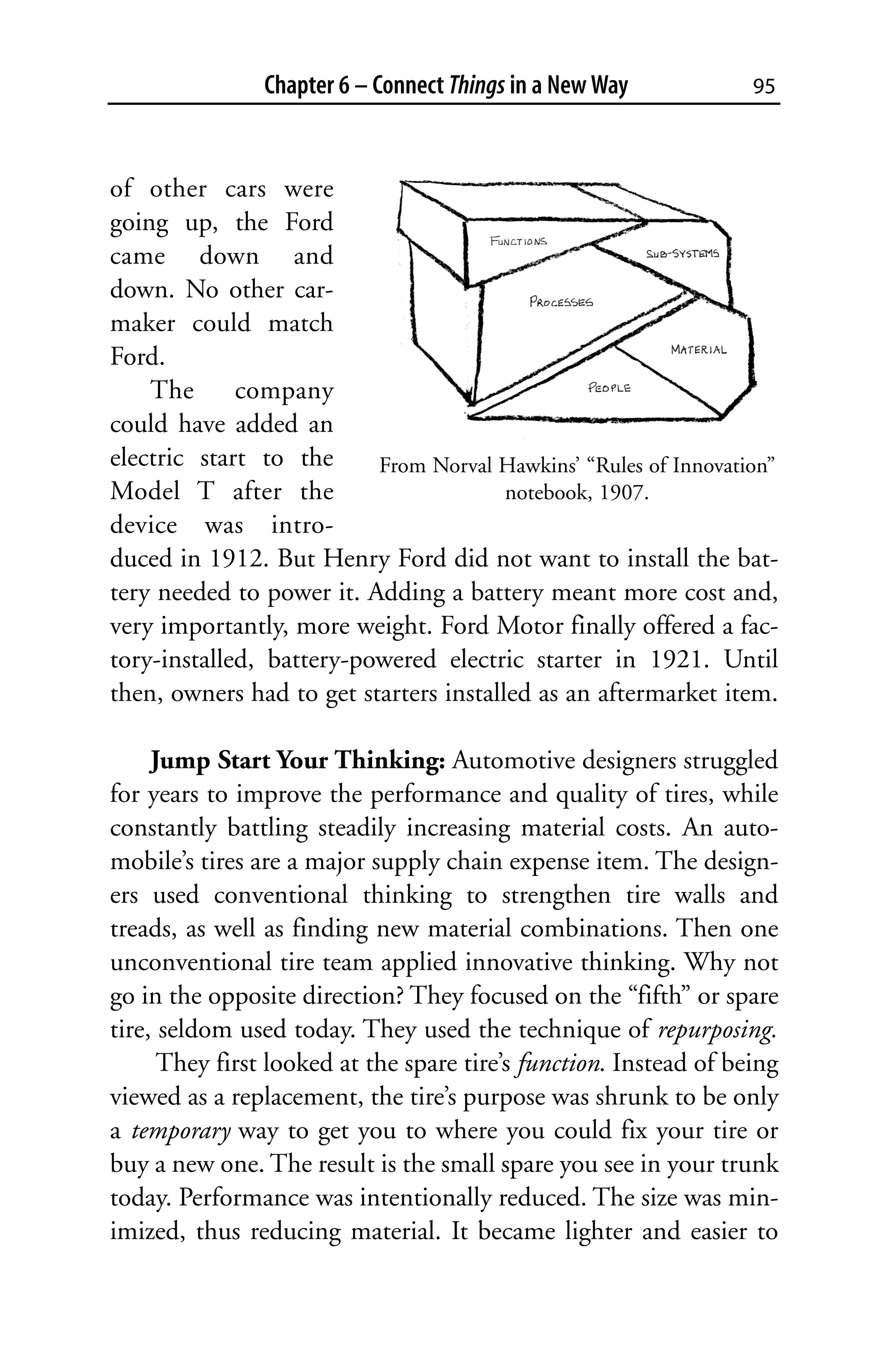

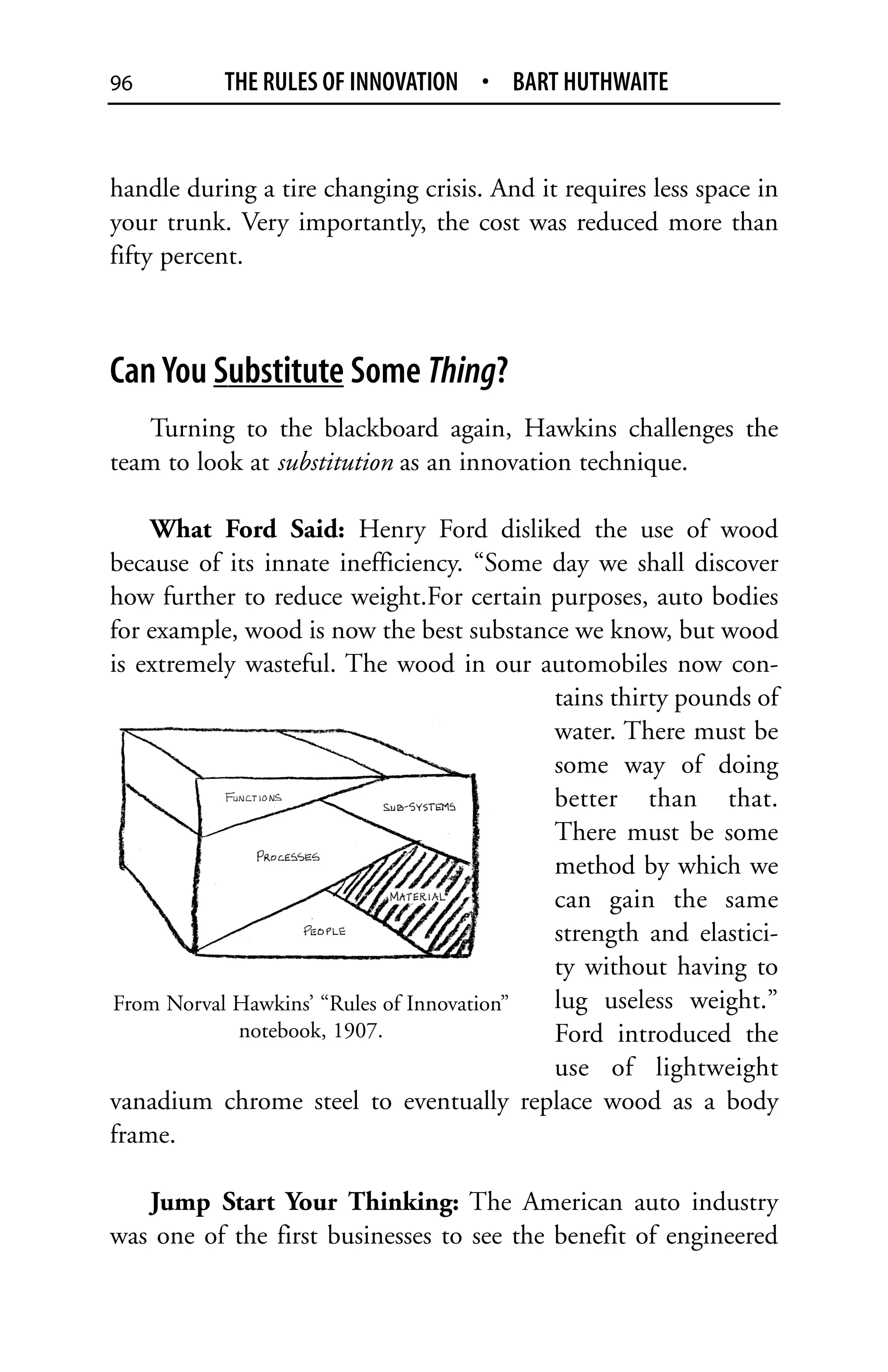

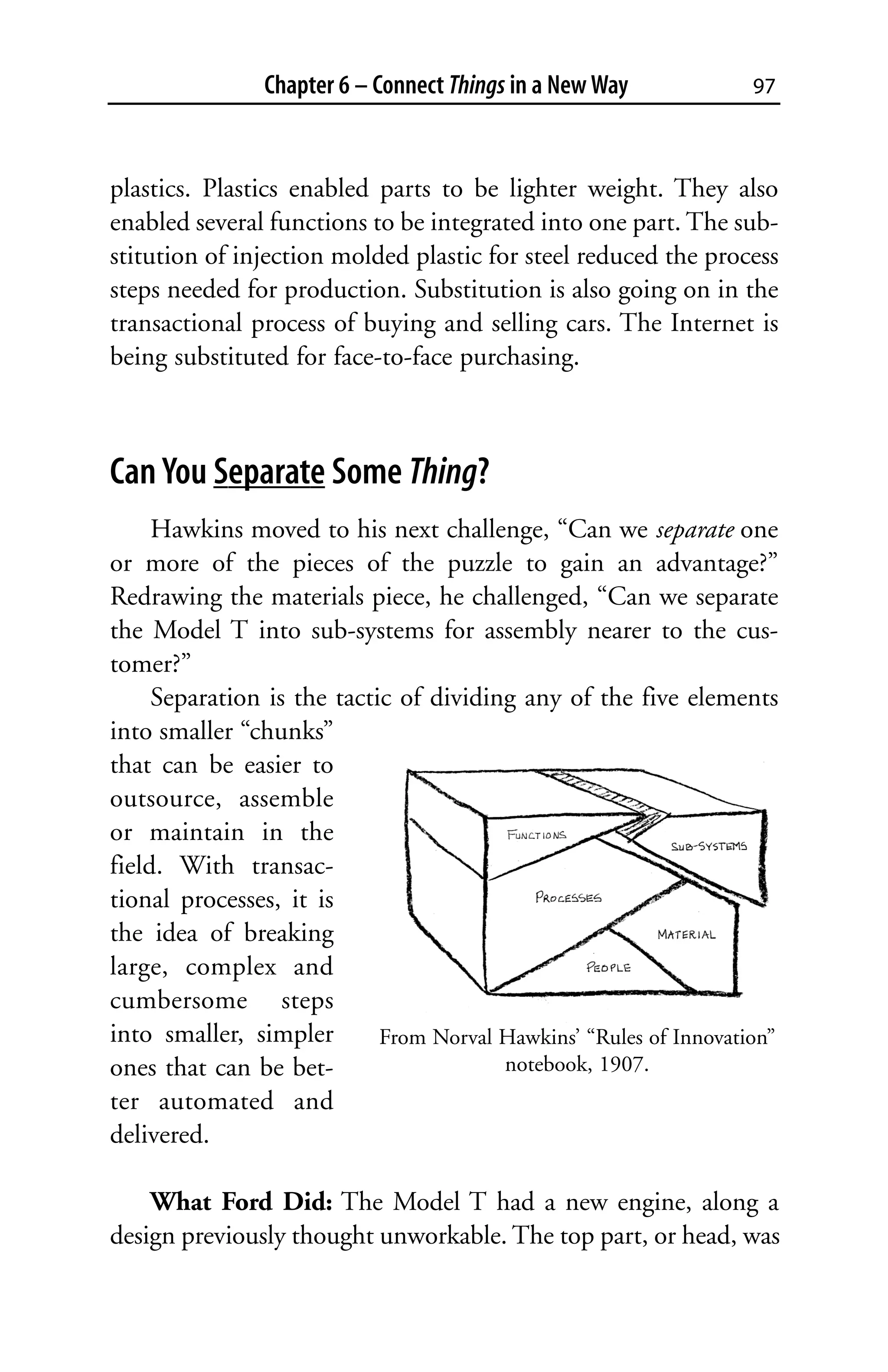

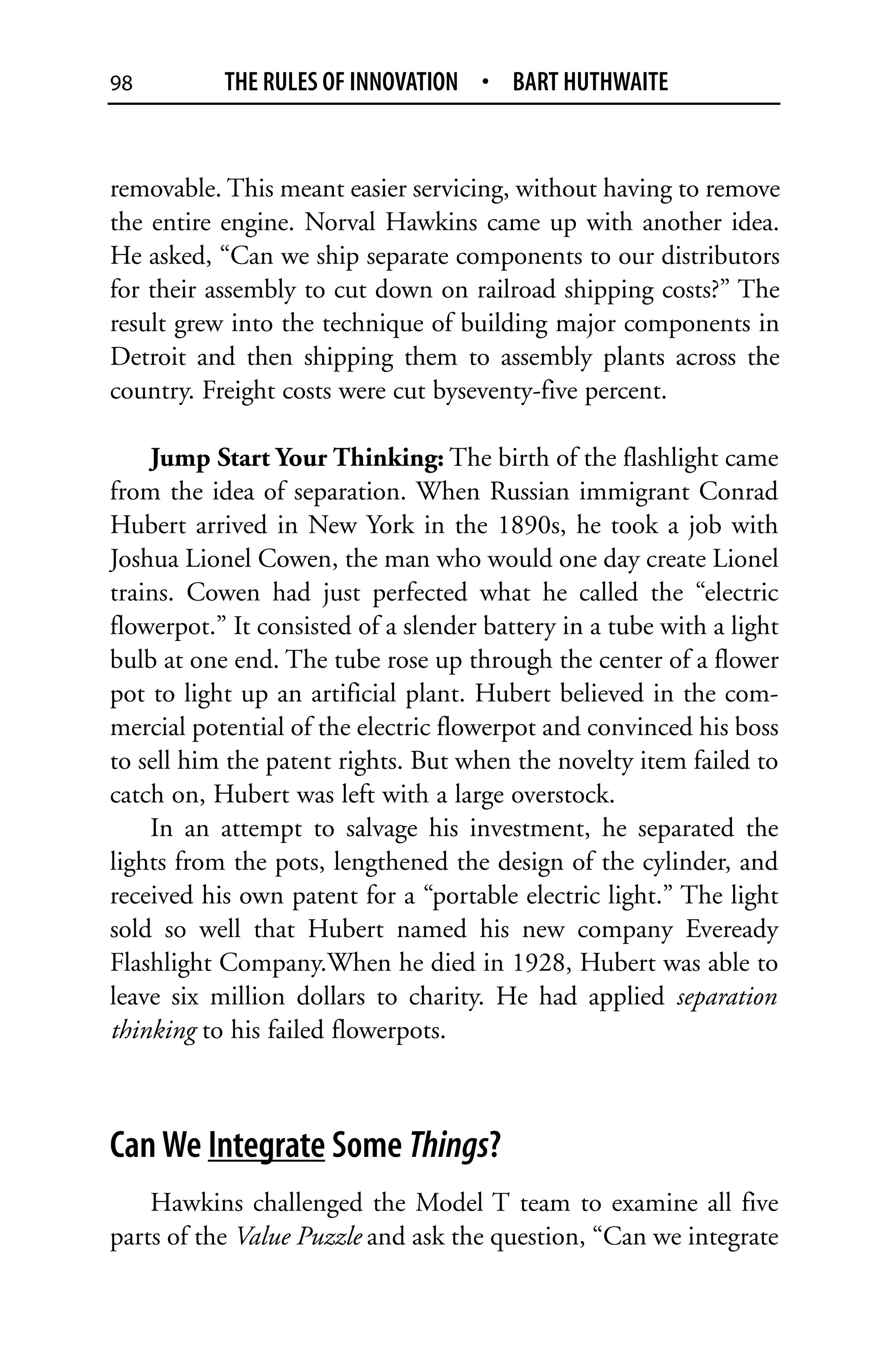

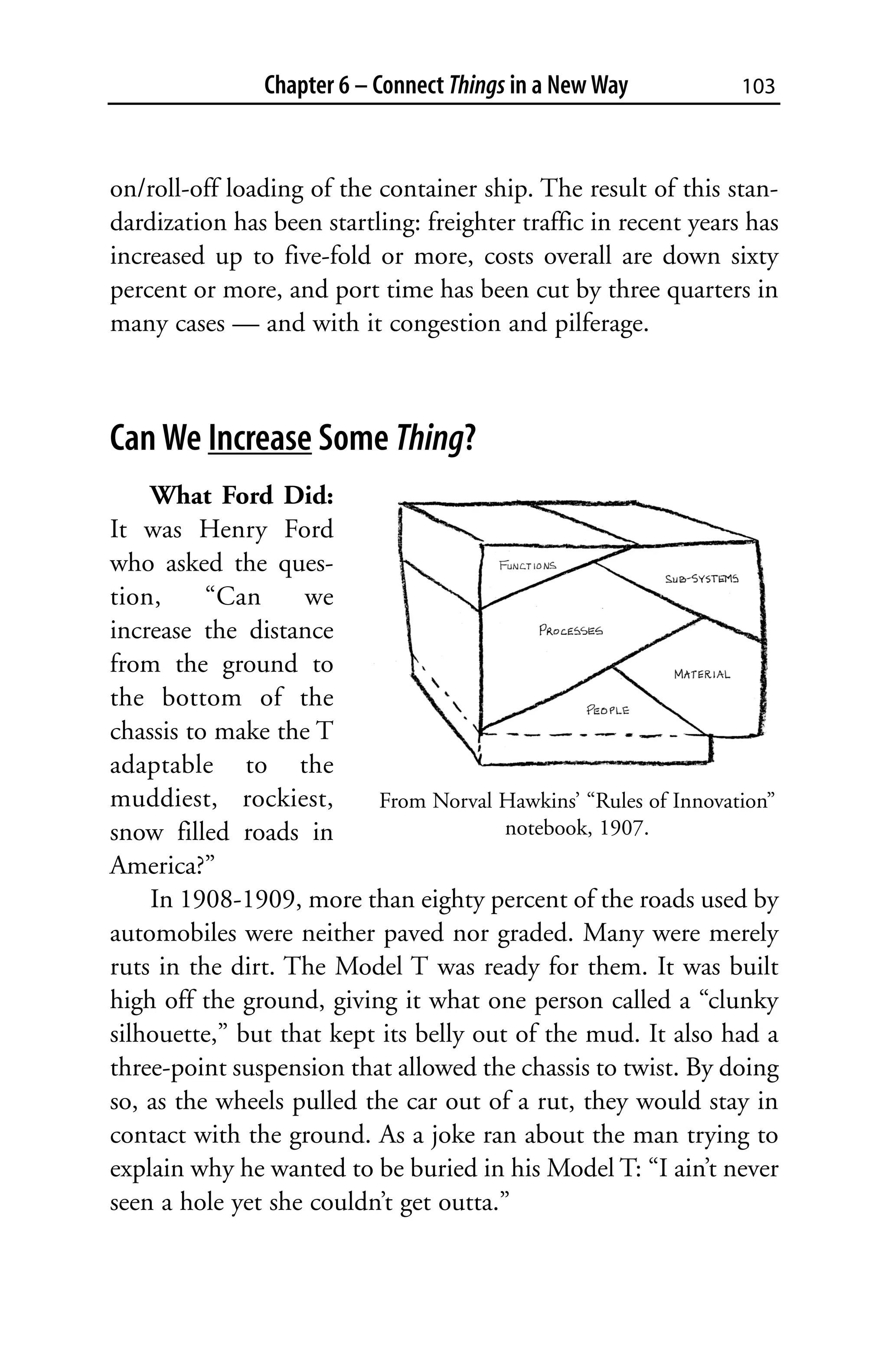

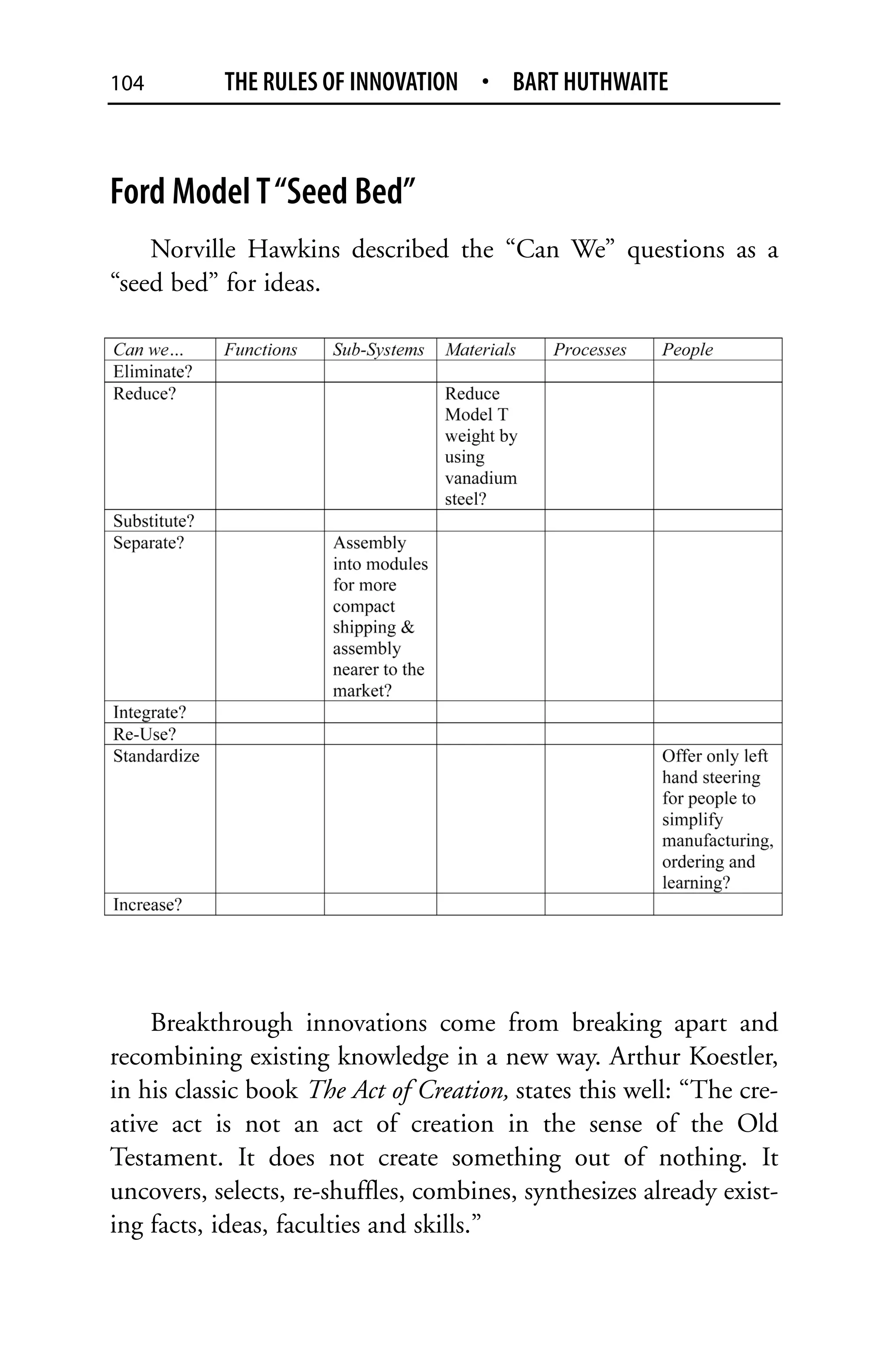

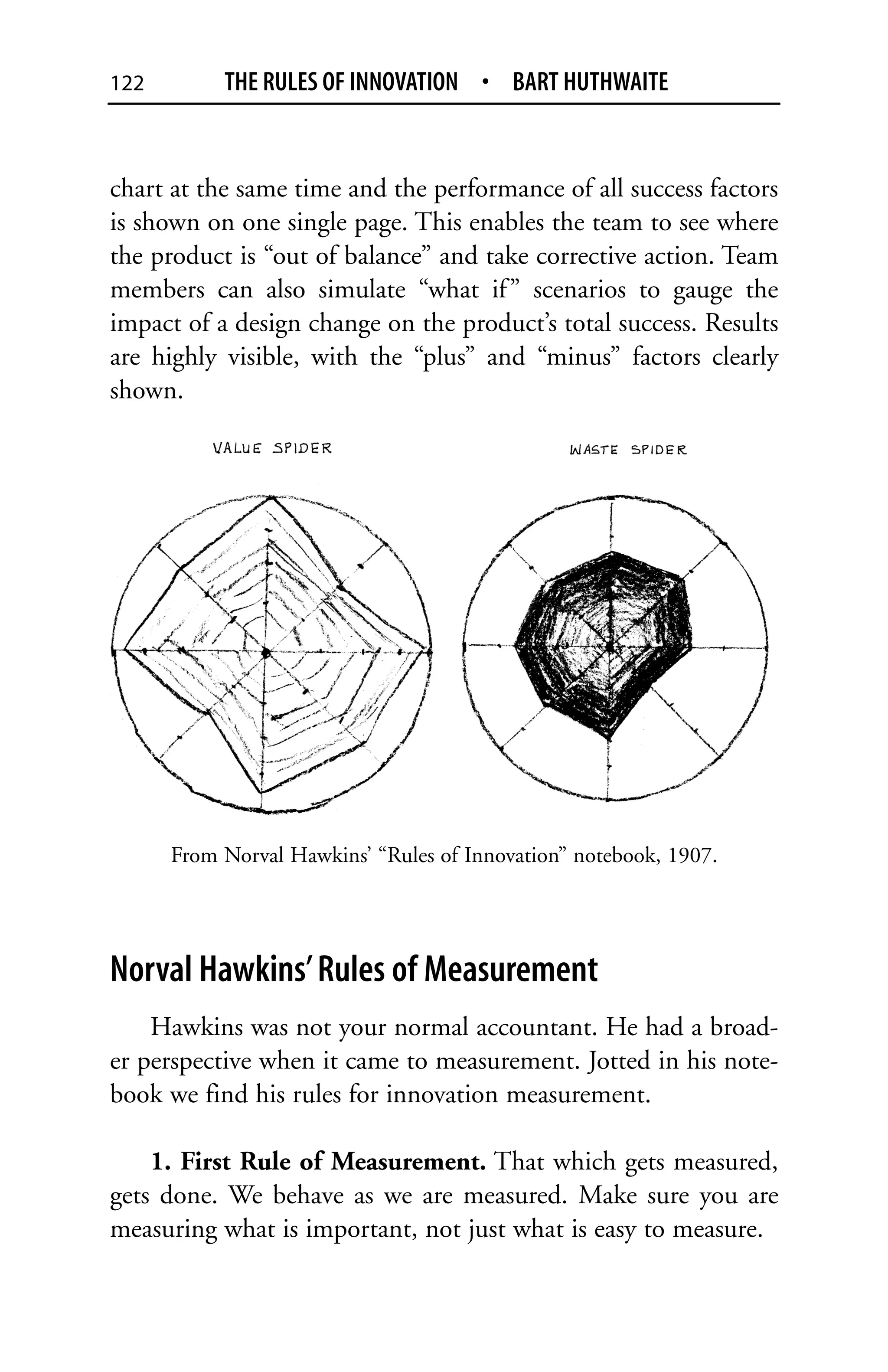

Hawkins developed an "innovation cube" process to help Henry Ford and his team create the Model T automobile. The cube illustrated a step-by-step method for innovation that considered all stakeholders. While Hawkins was a real person, the details of the cube are fictionalized to teach innovation lessons. The Model T was hugely successful but Ford later broke his own rules, nearly losing the company.