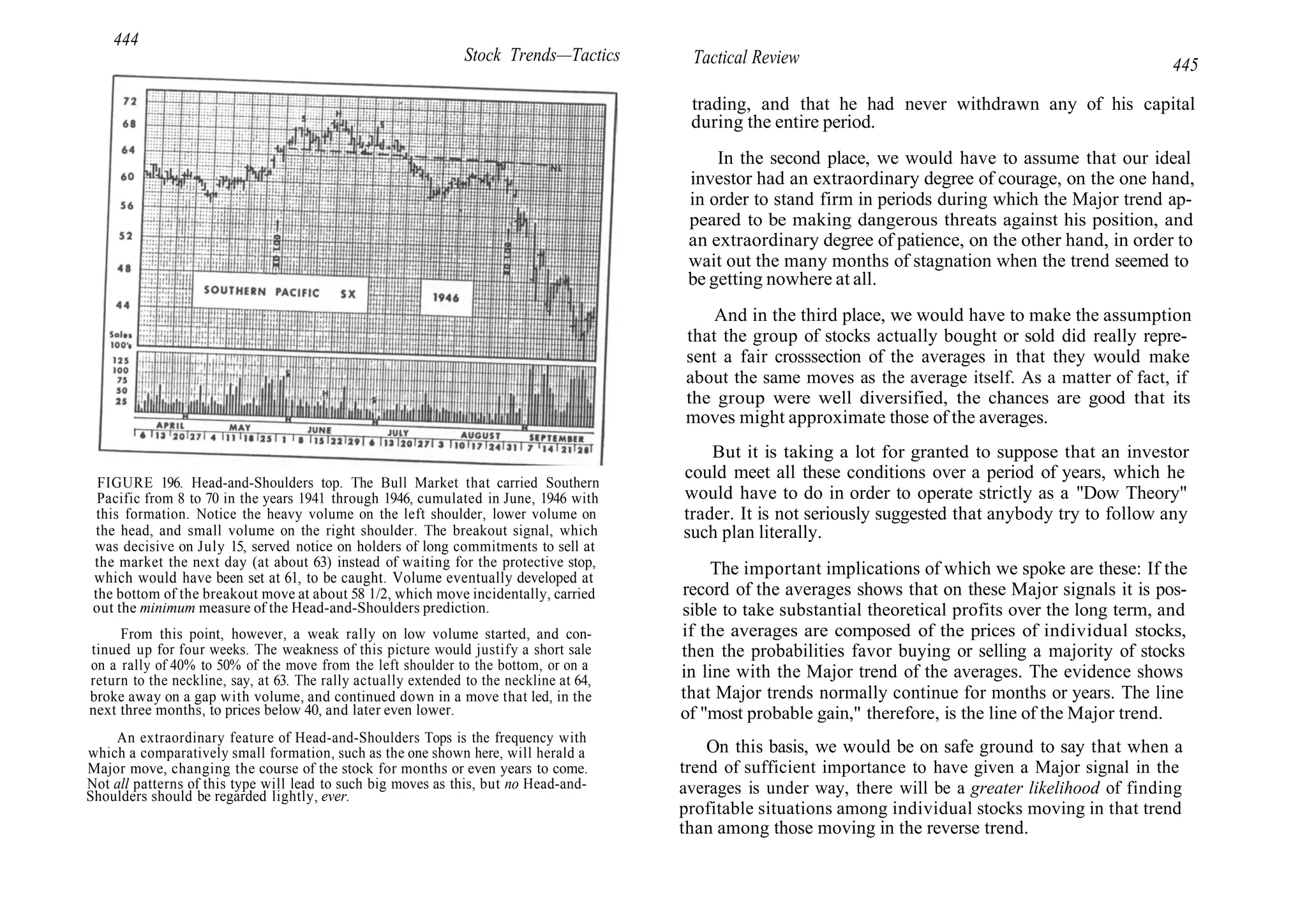

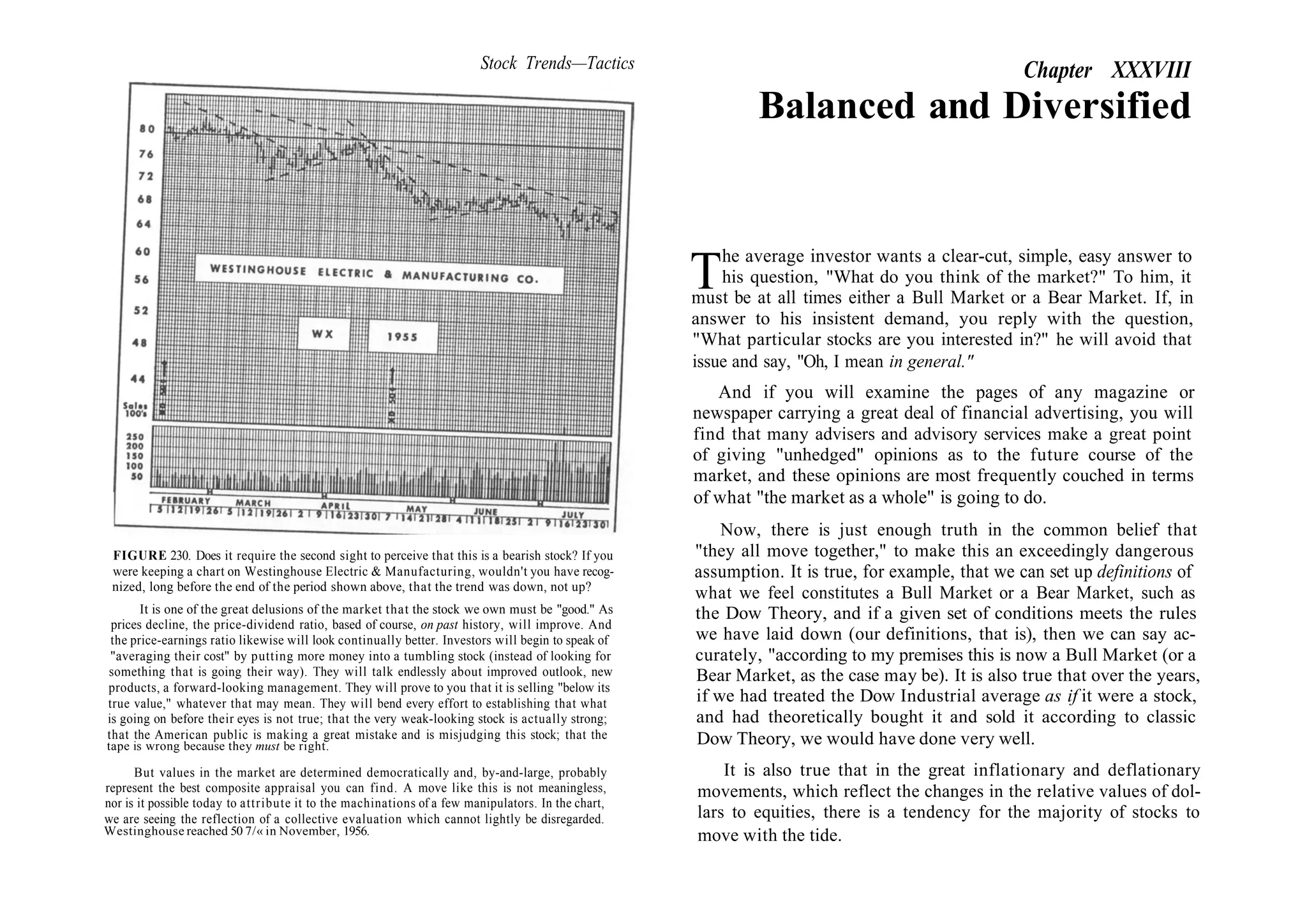

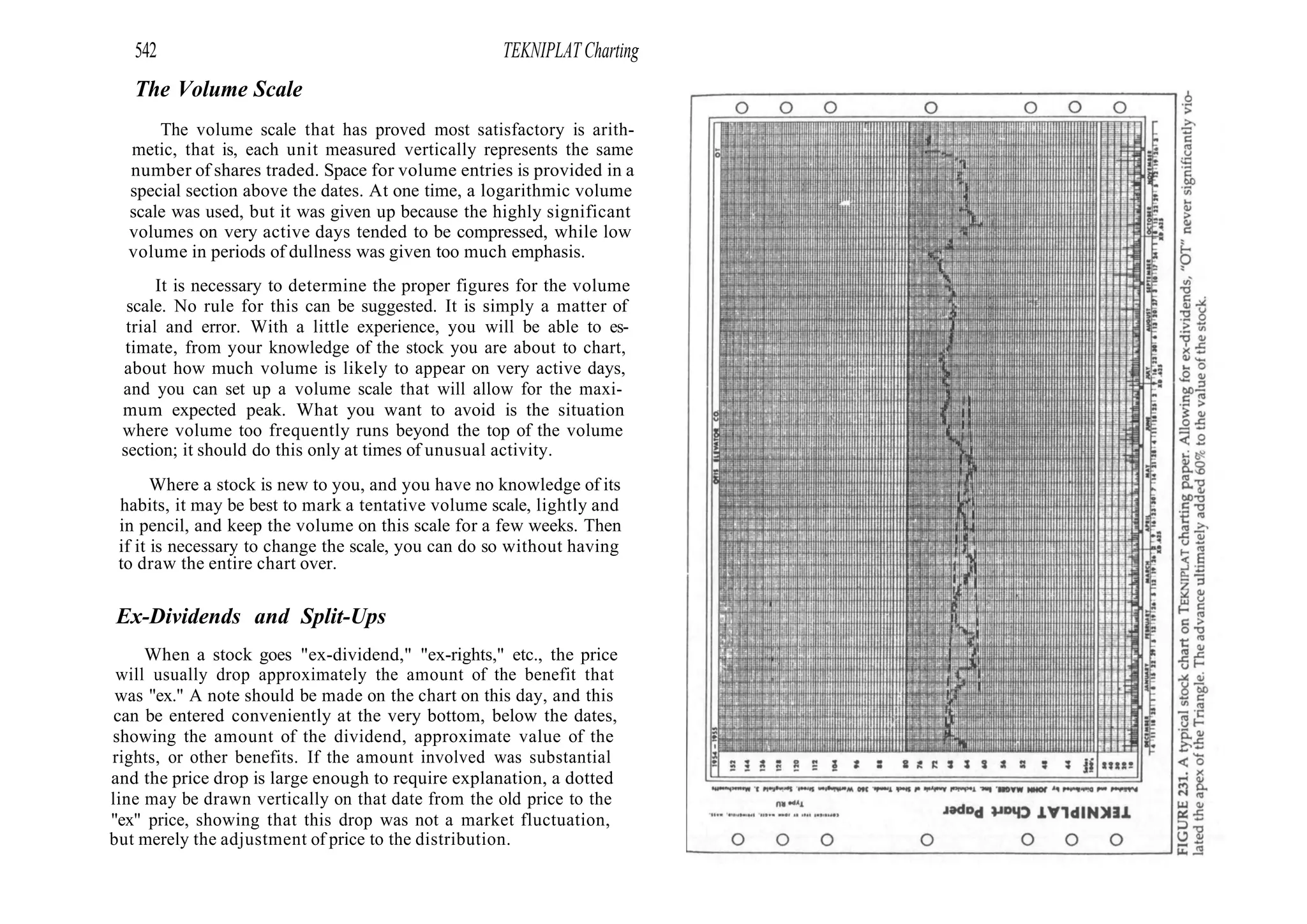

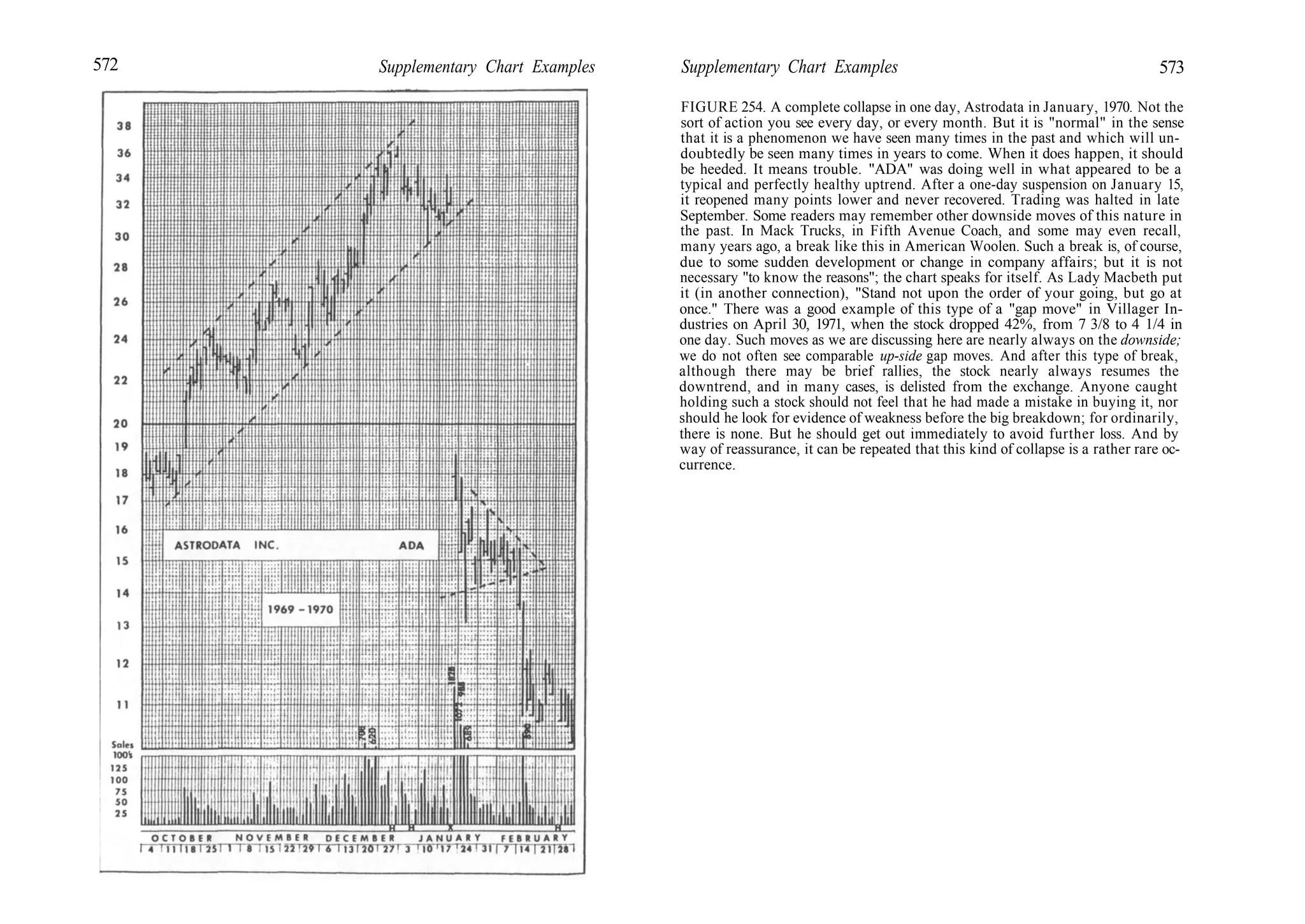

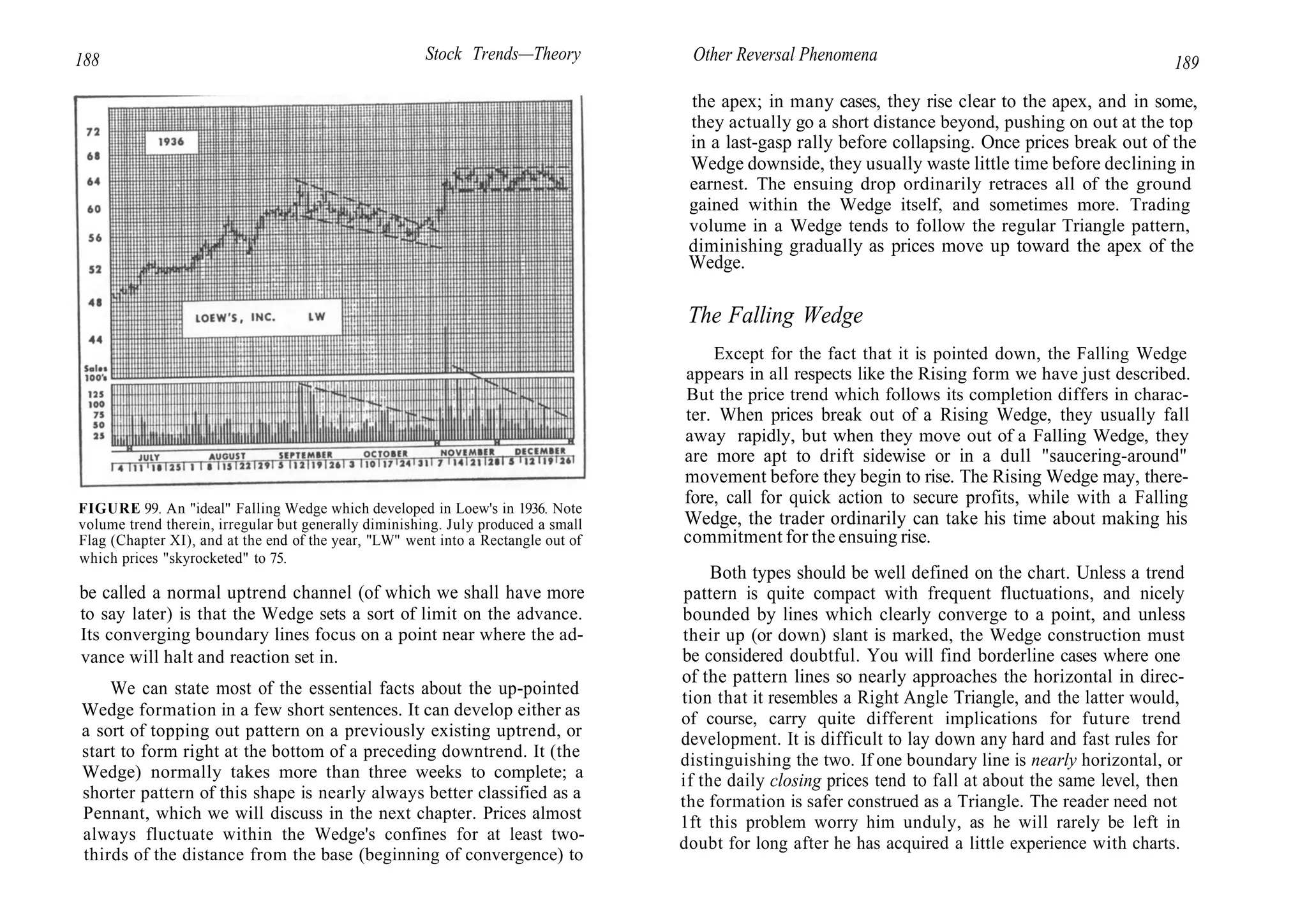

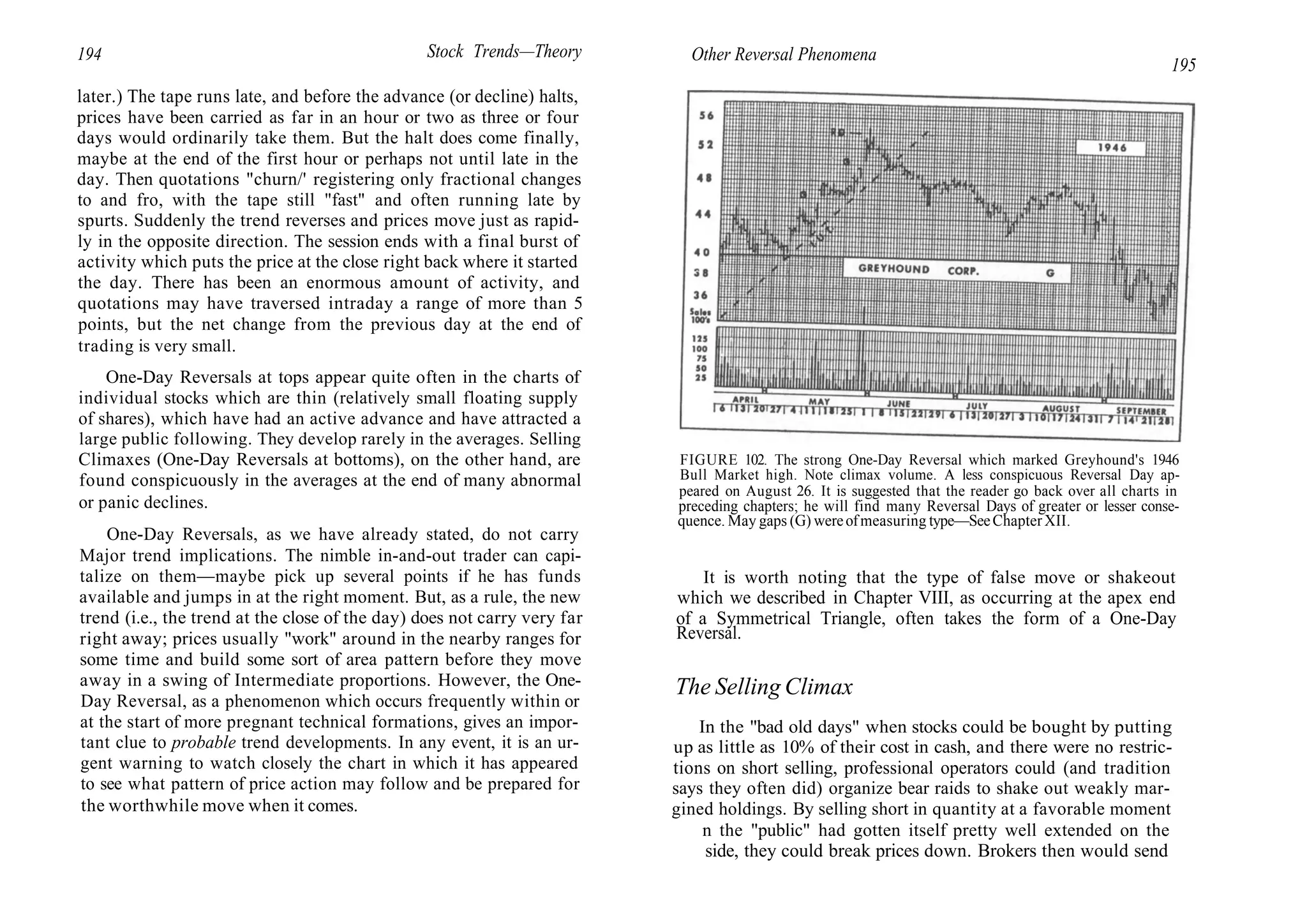

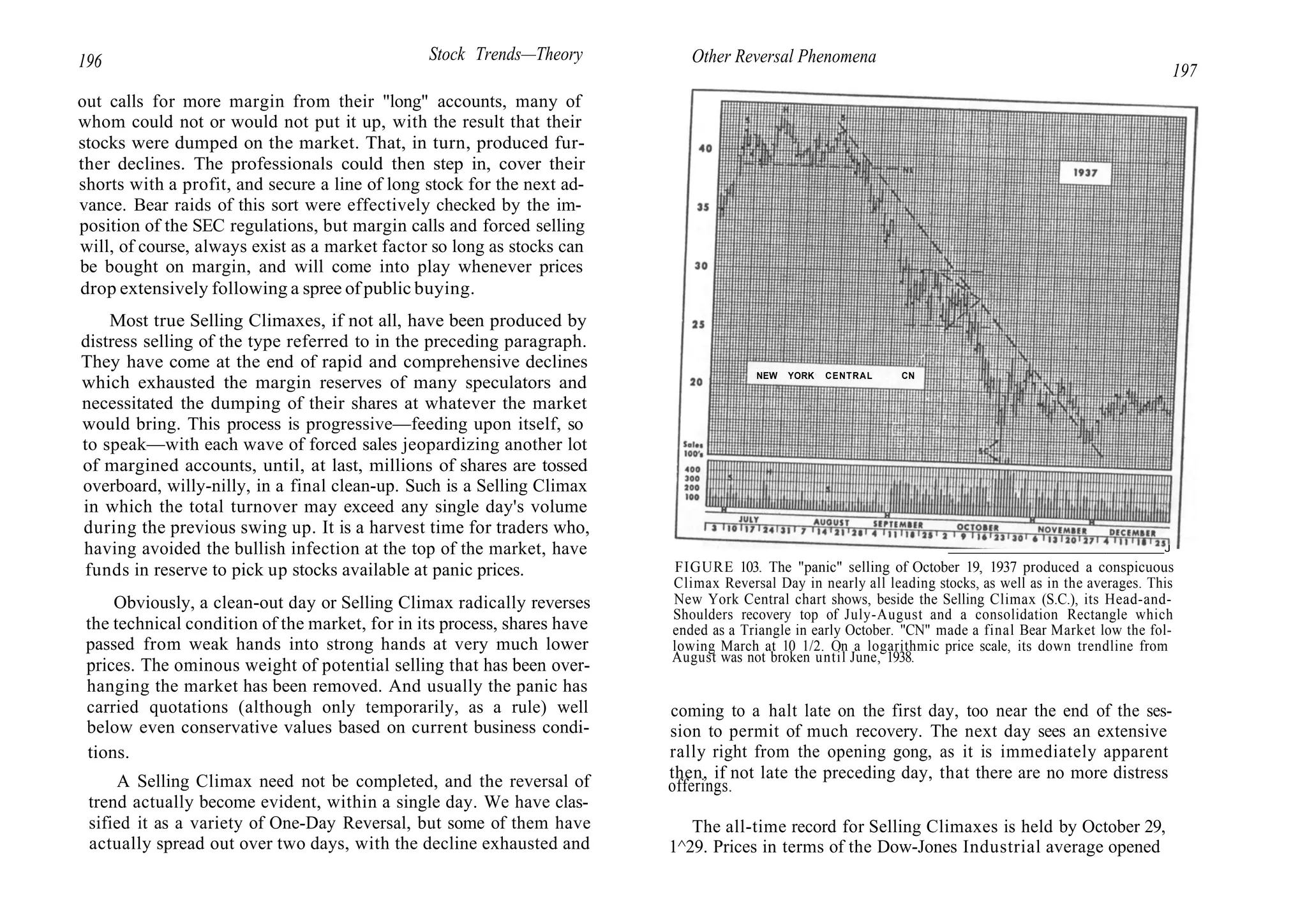

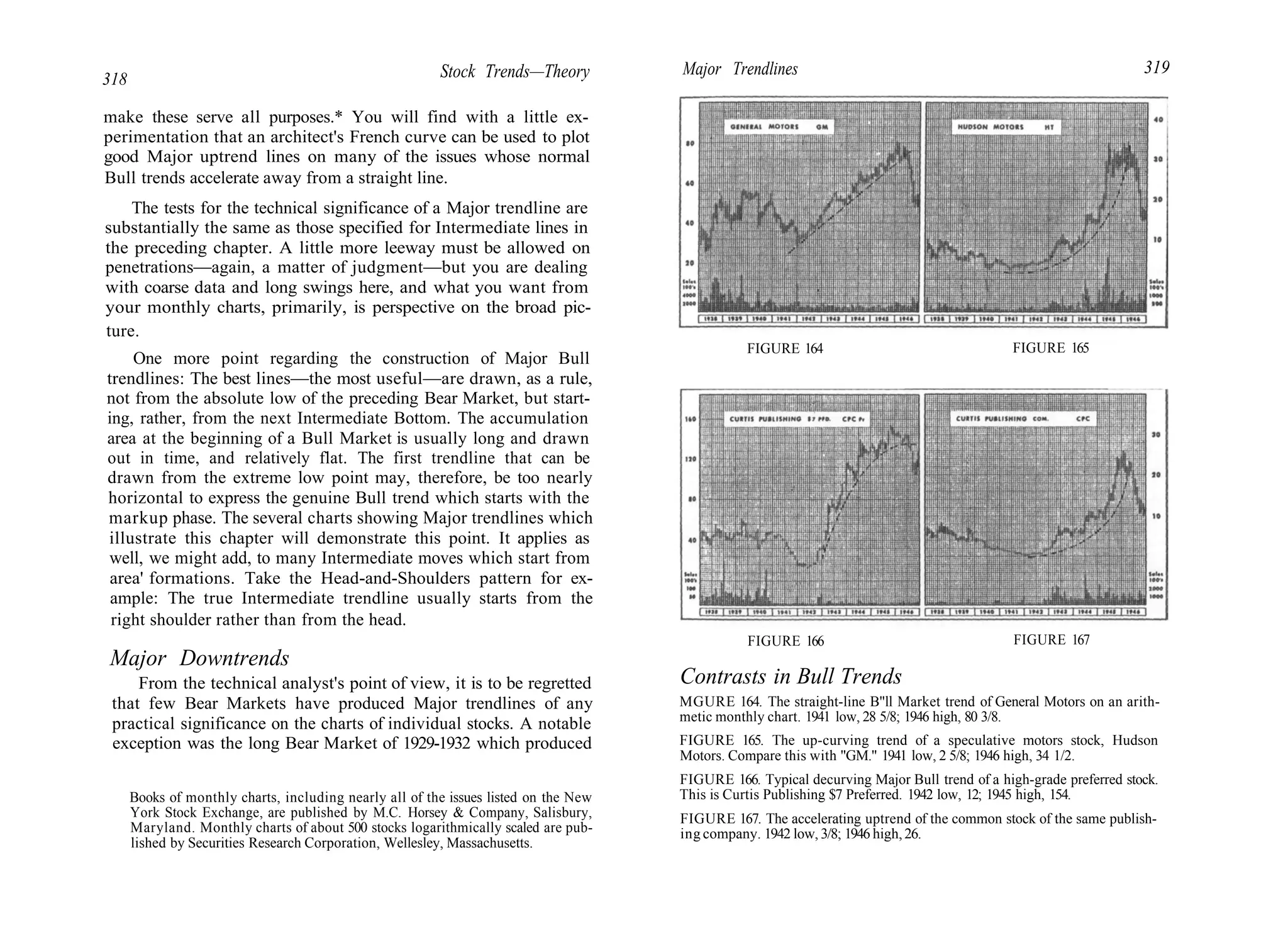

This document discusses stock charts and technical analysis. It describes how to construct basic daily stock charts using high, low, closing price and volume data from financial newspapers. Different types of charts and scales are discussed, with a recommendation to use semilogarithmic scales which show percentage changes rather than arithmetic scales which show dollar changes. The document emphasizes that charts are the primary tools of technical analysts to identify patterns in market data that may signal future stock price trends.

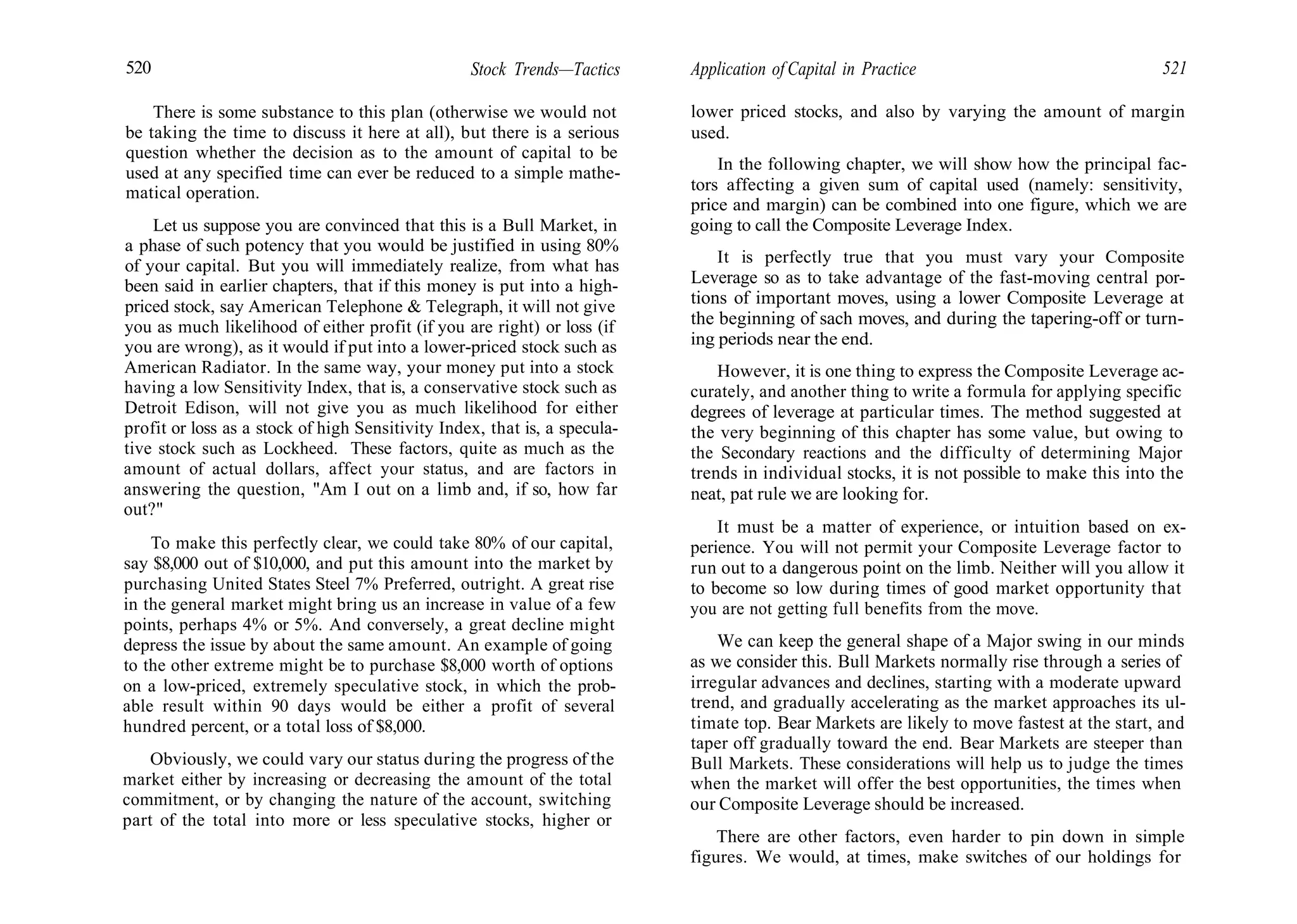

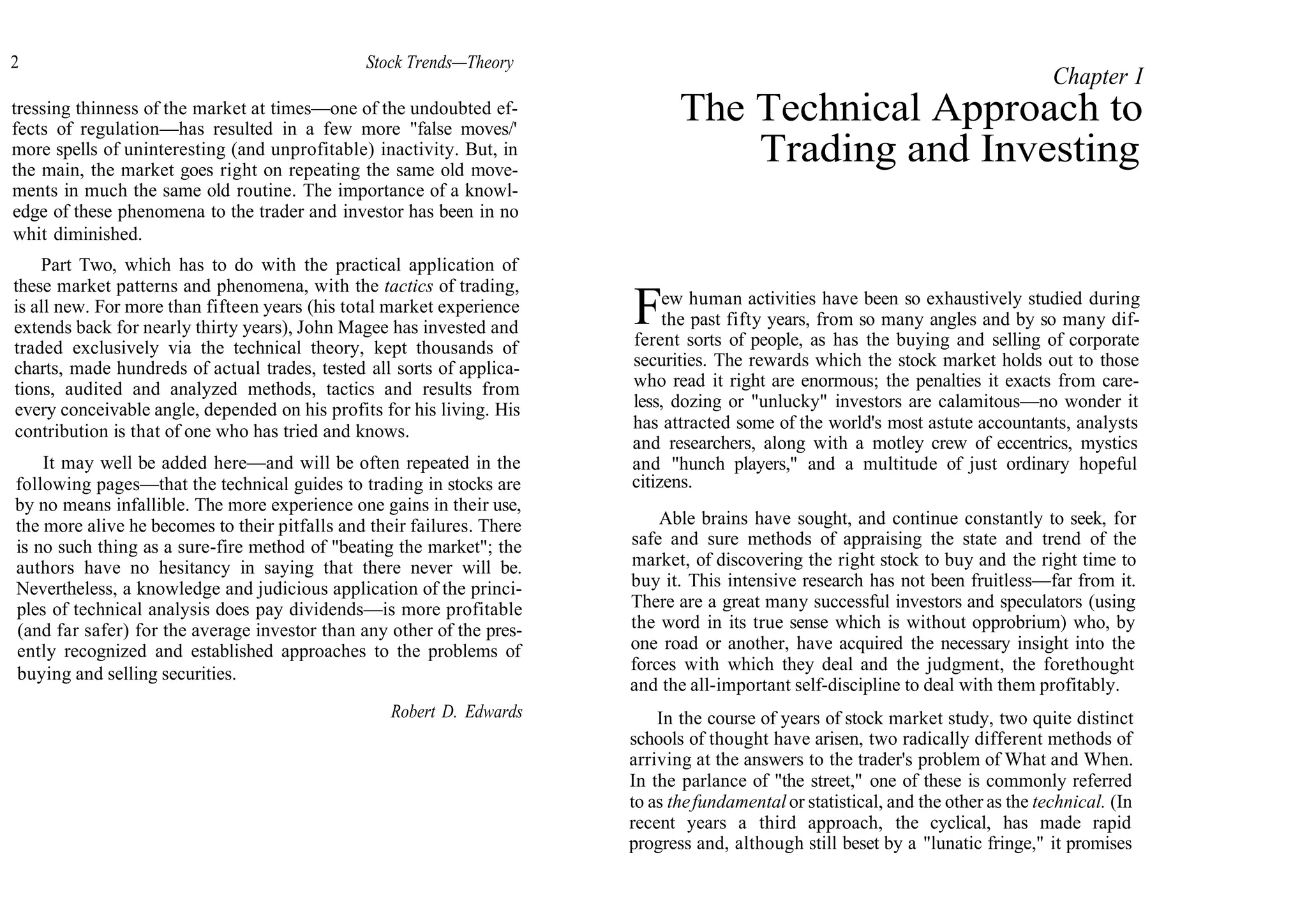

![426 Stock Trends—Tactics

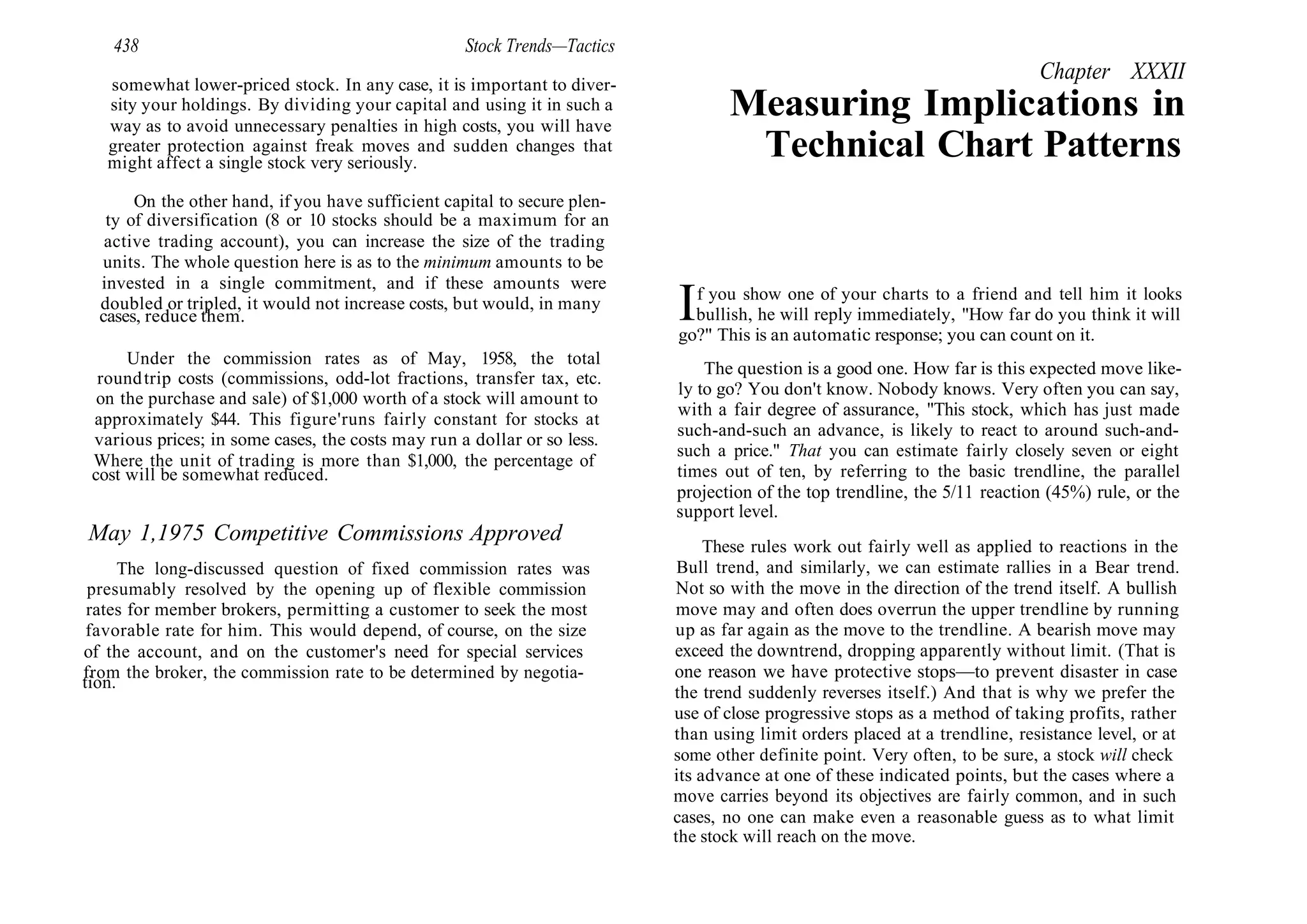

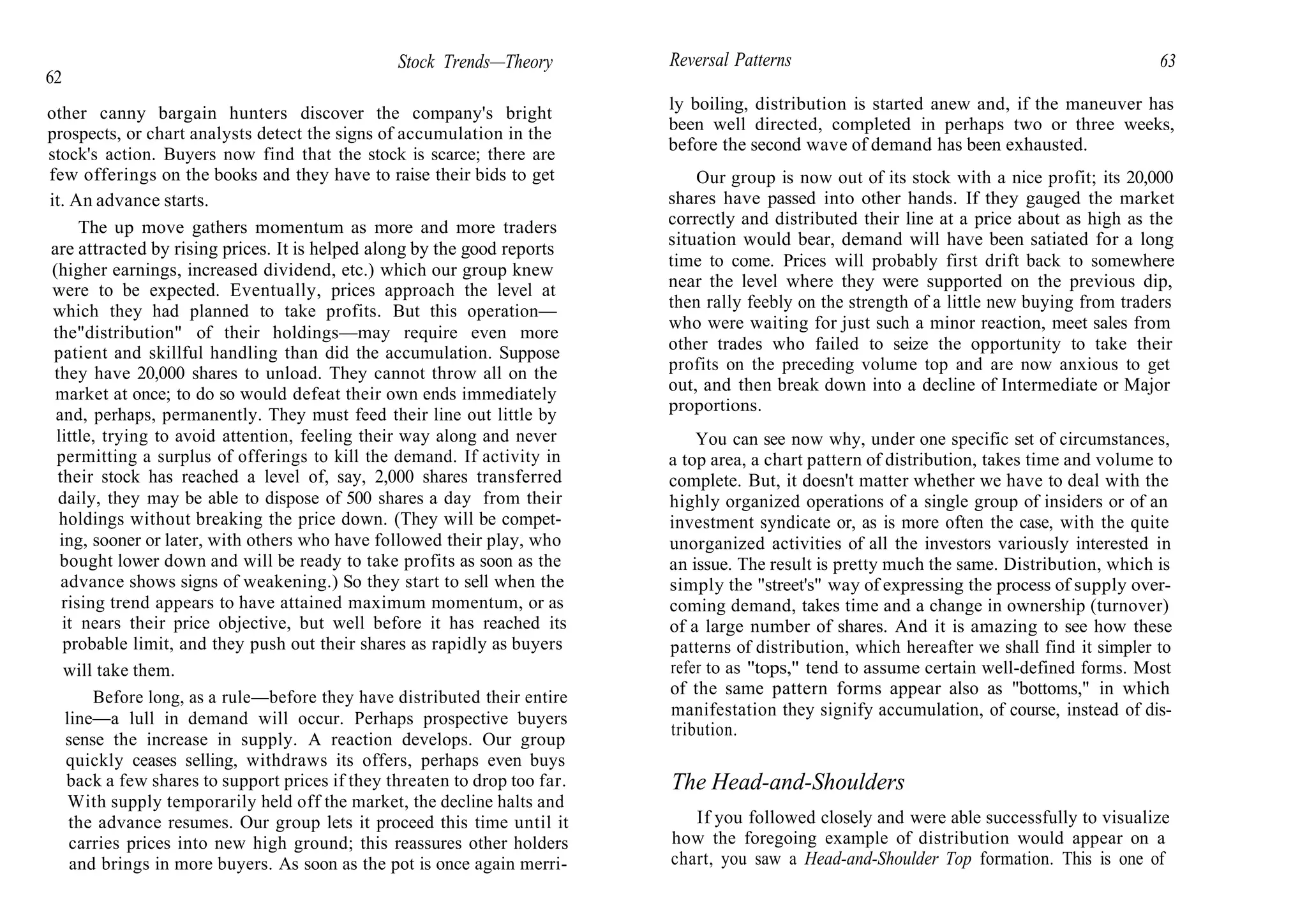

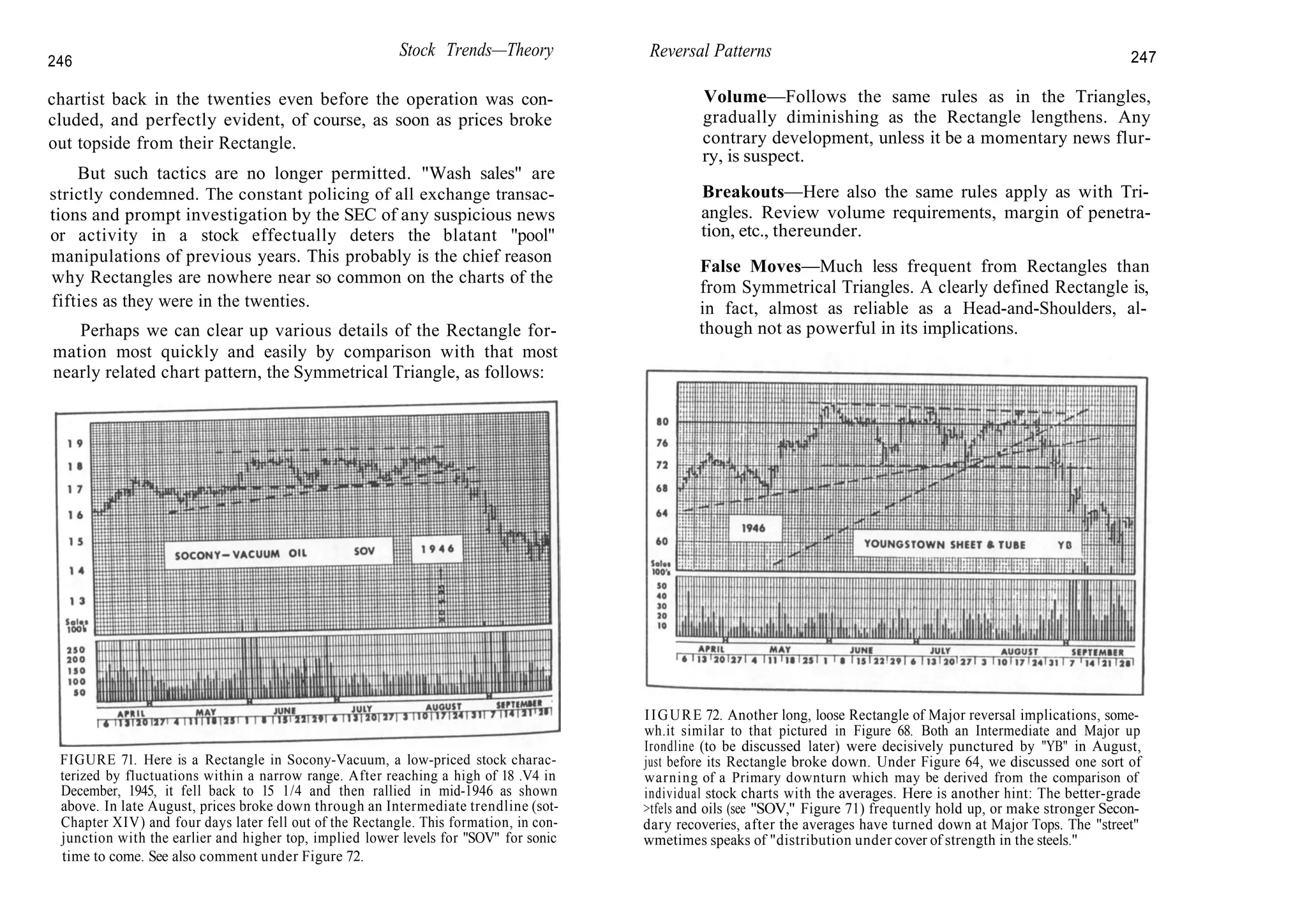

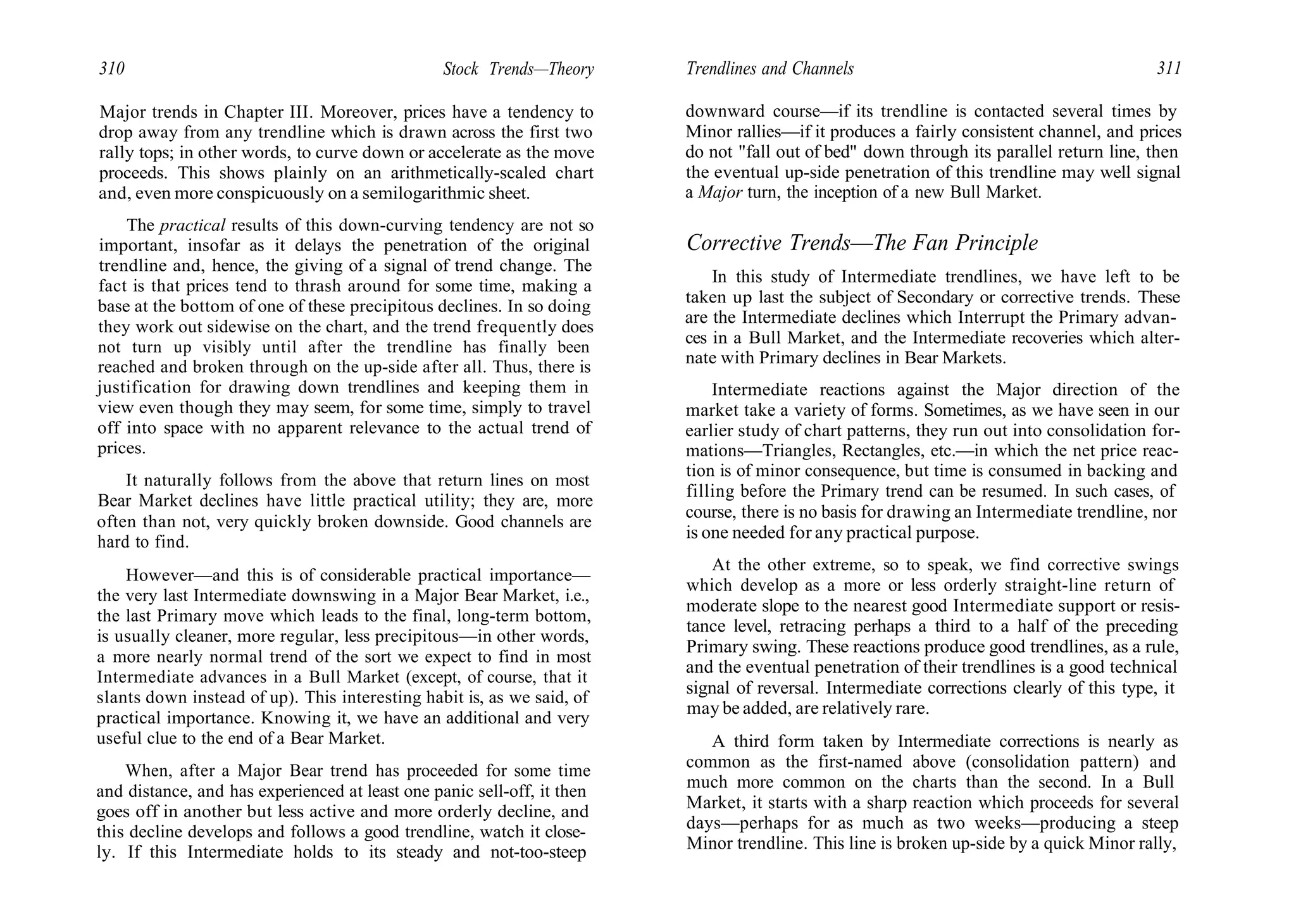

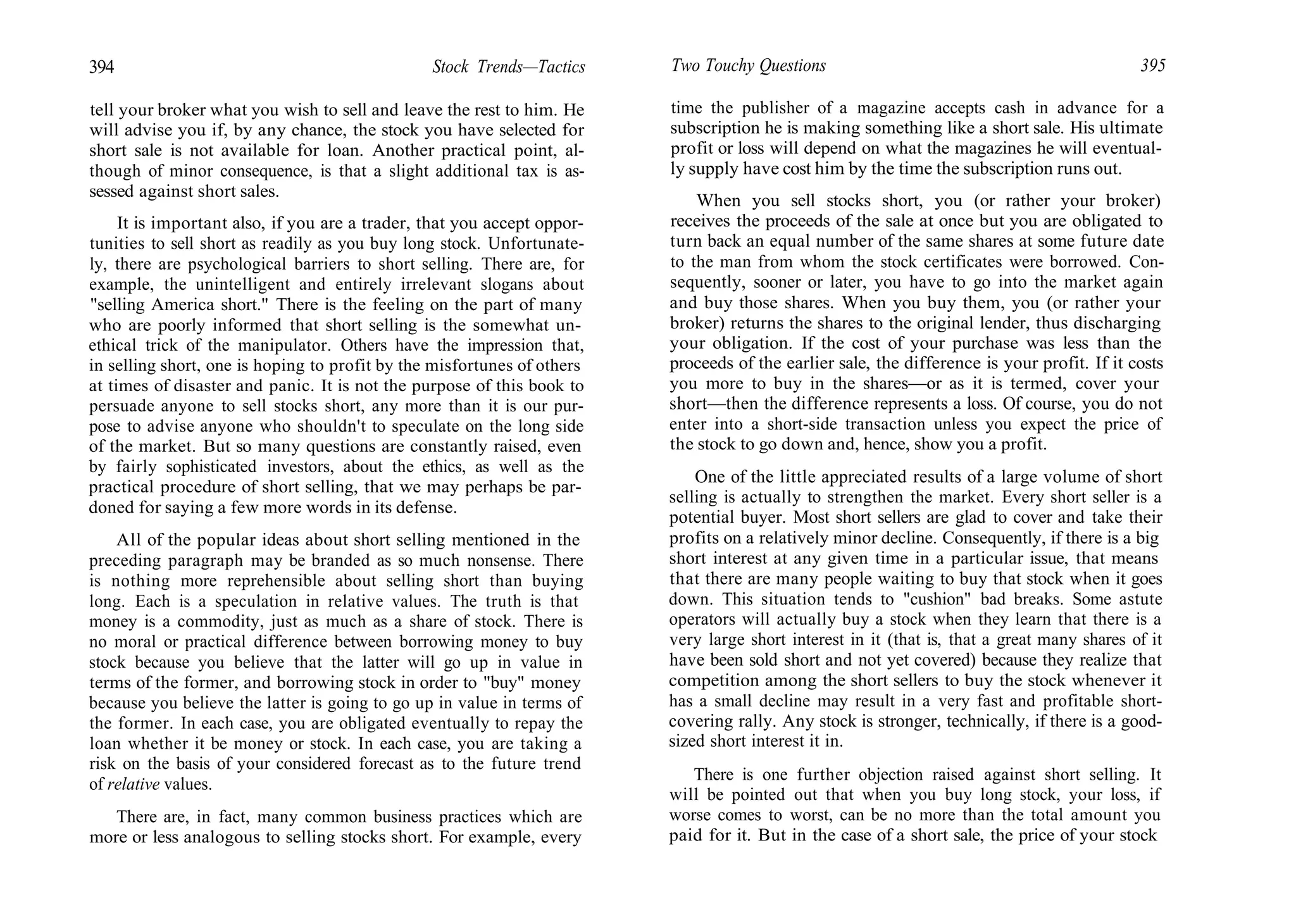

DIAGRAM 3 DIAGRAM 4

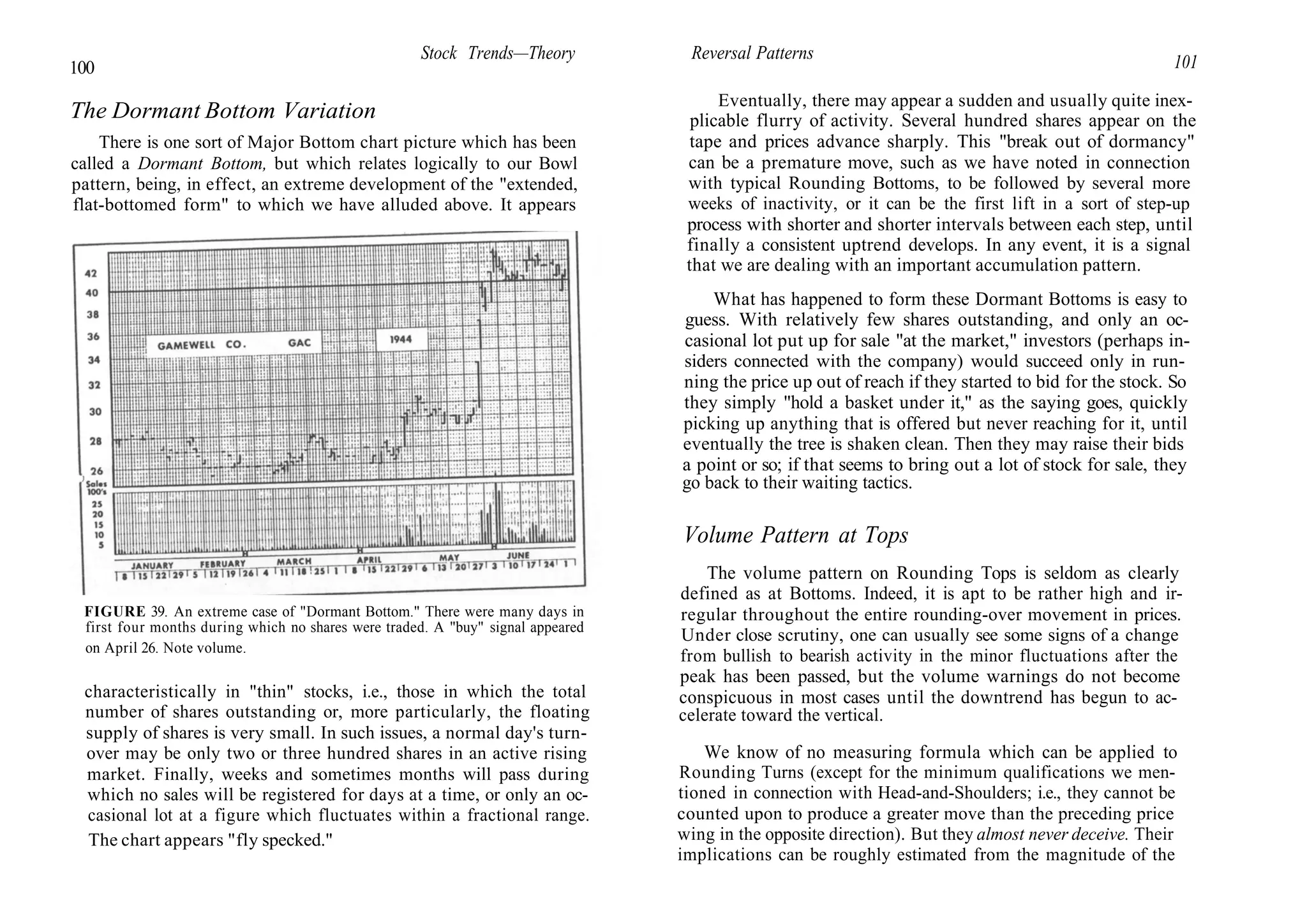

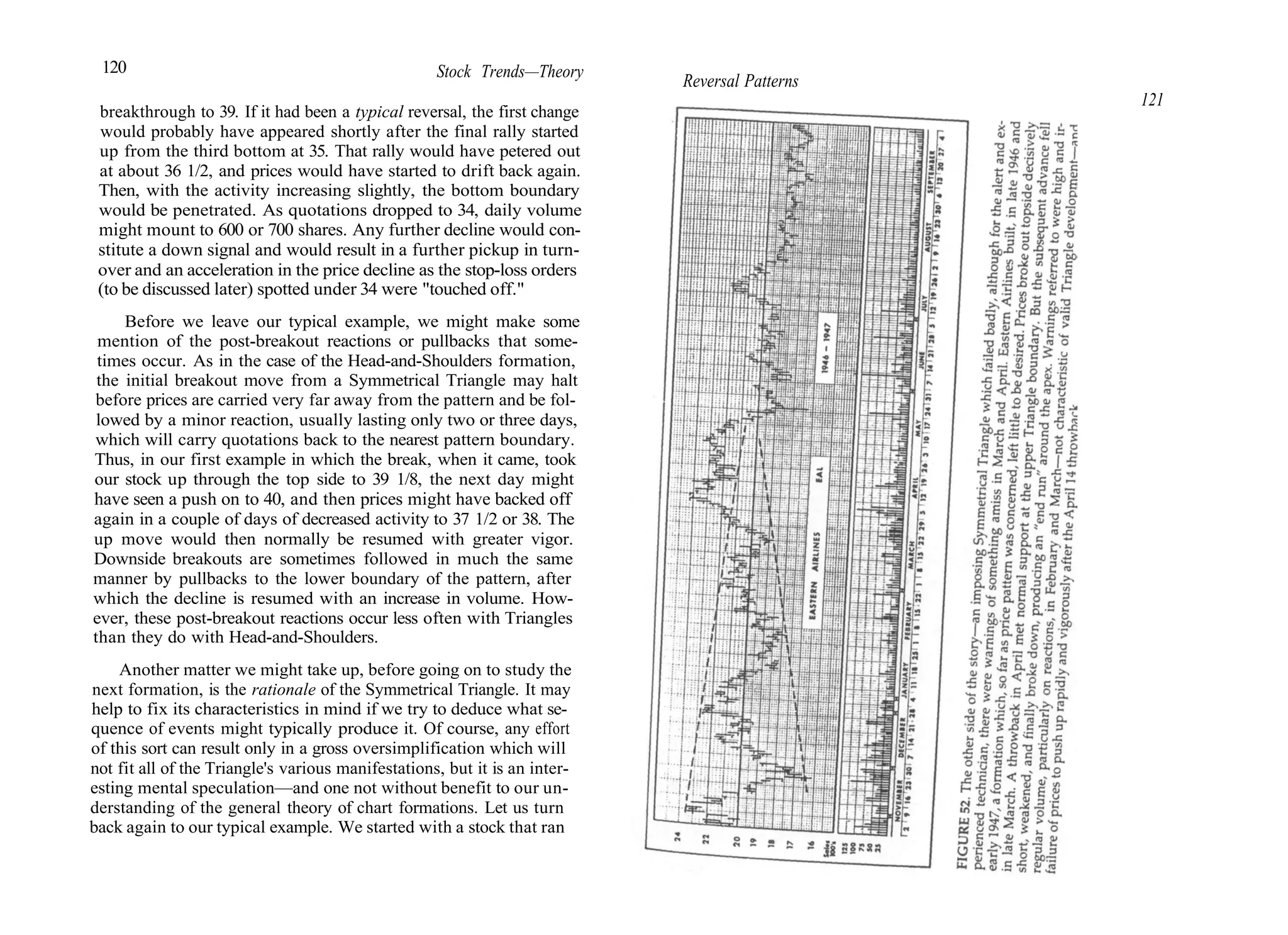

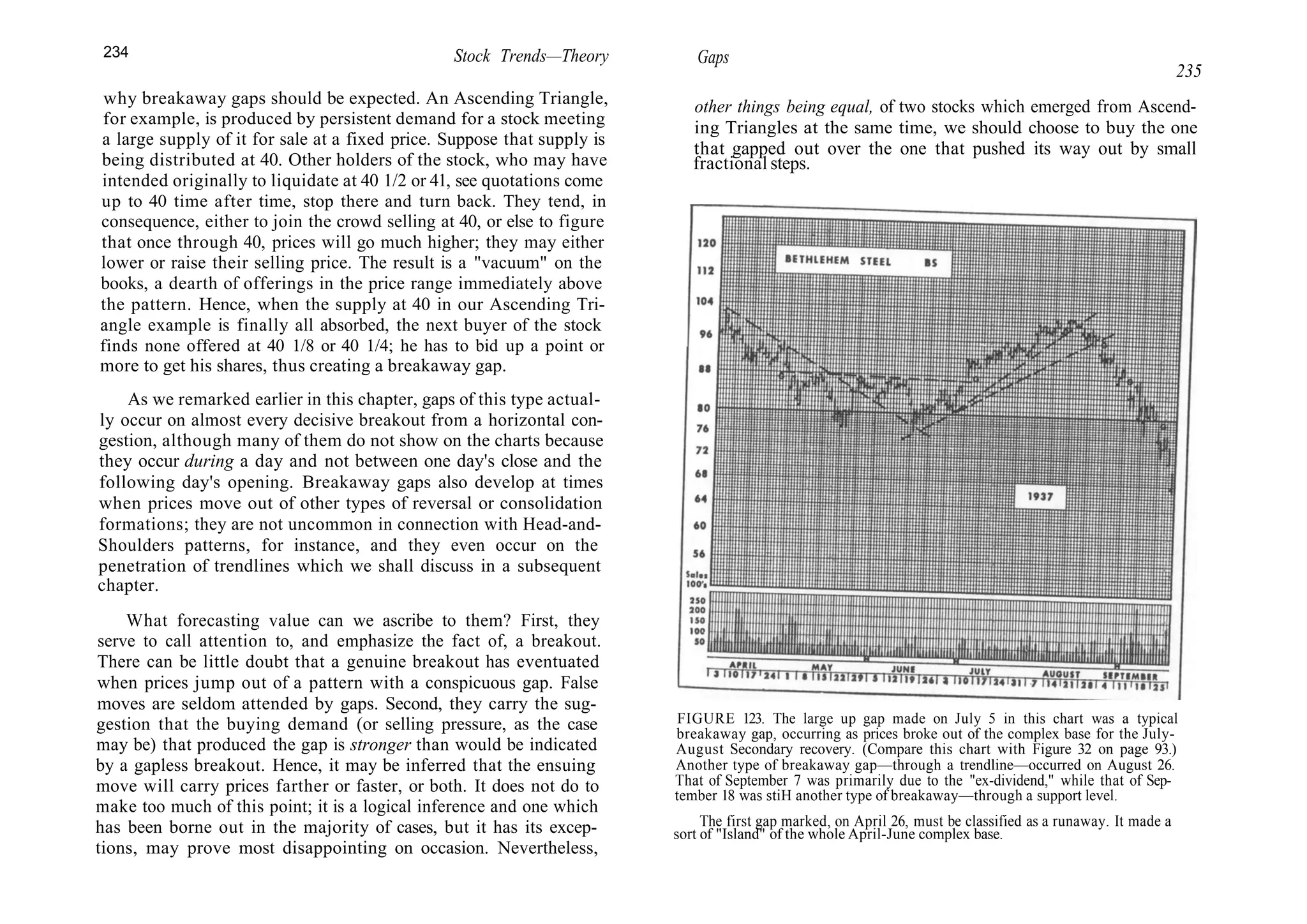

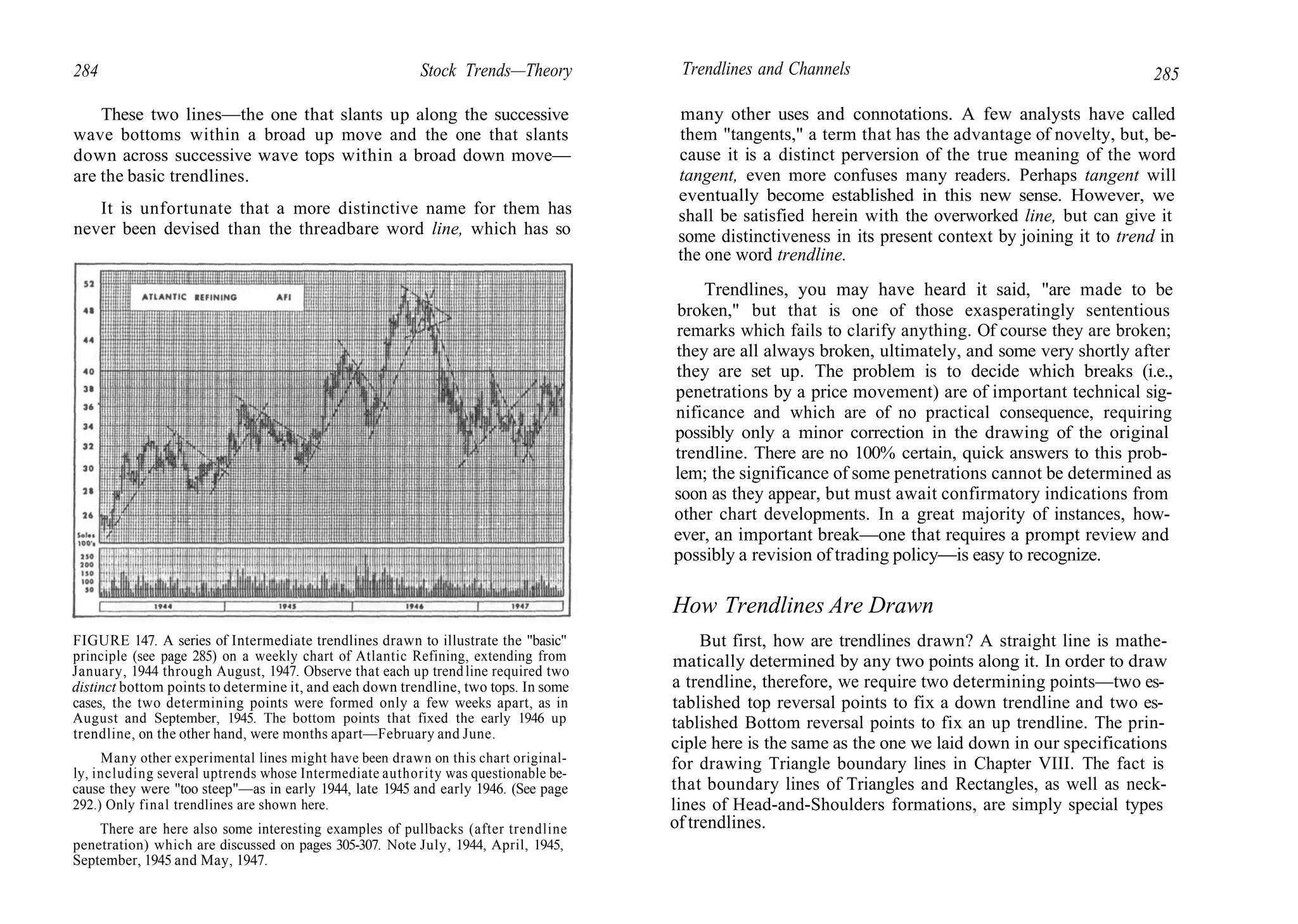

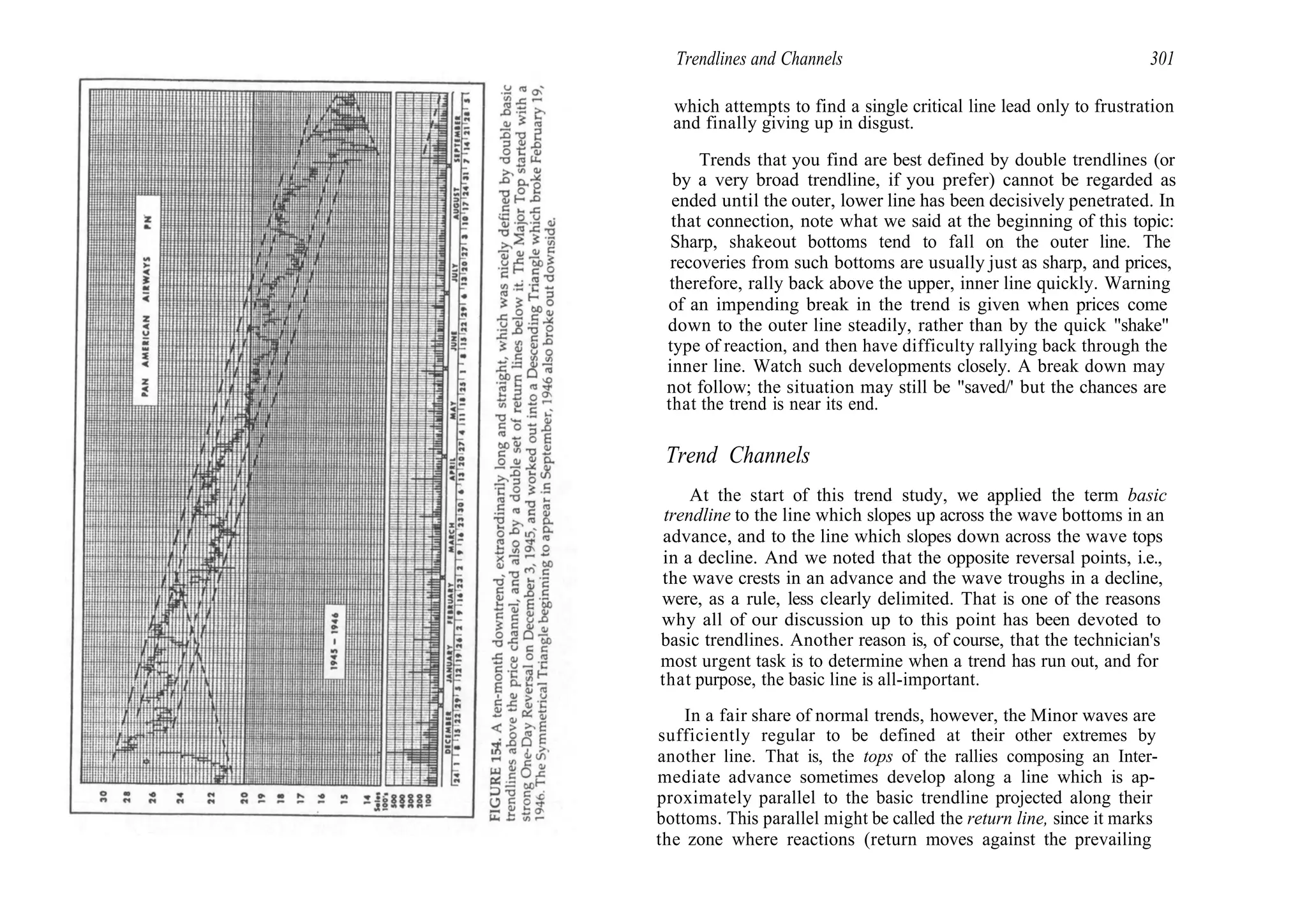

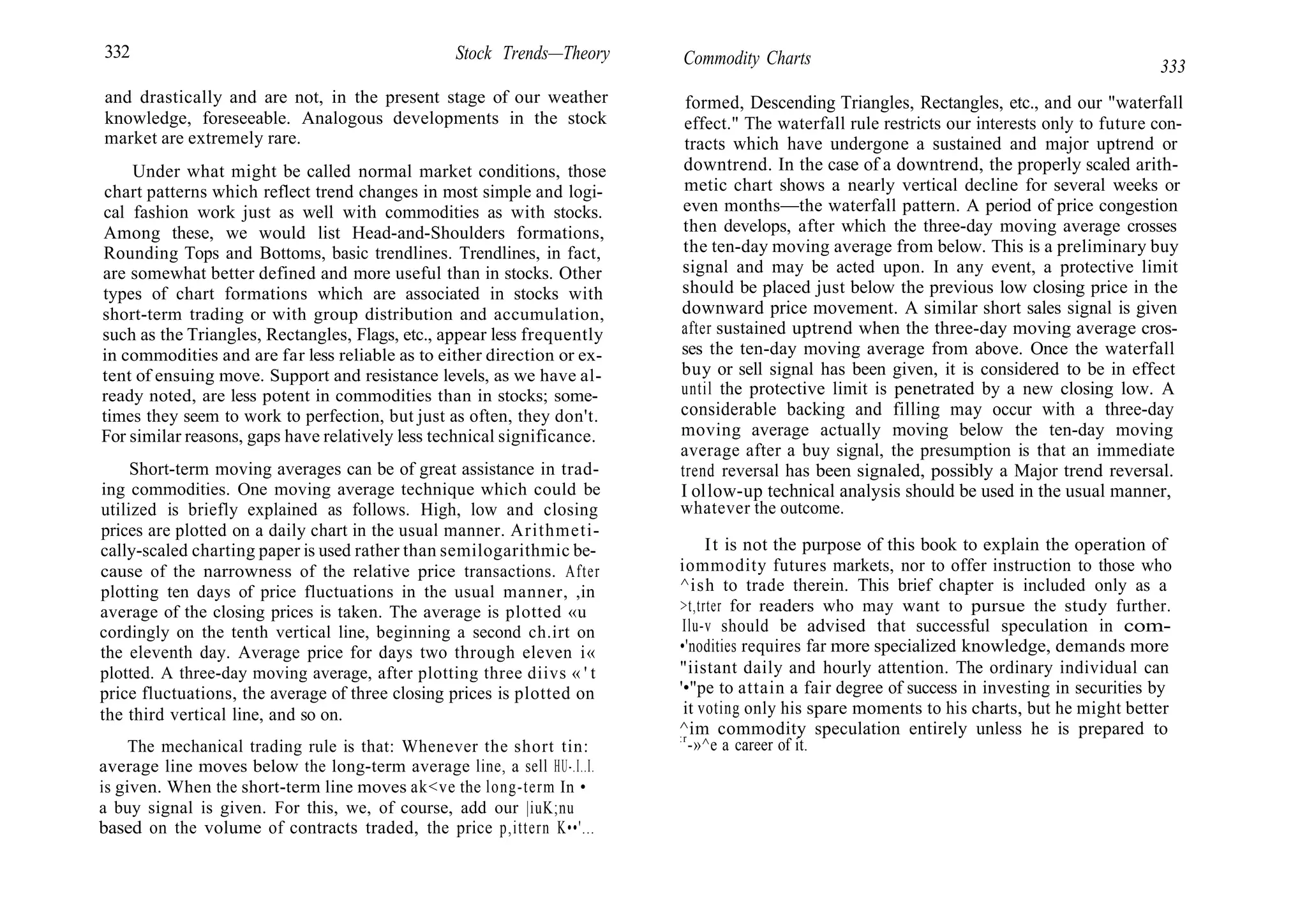

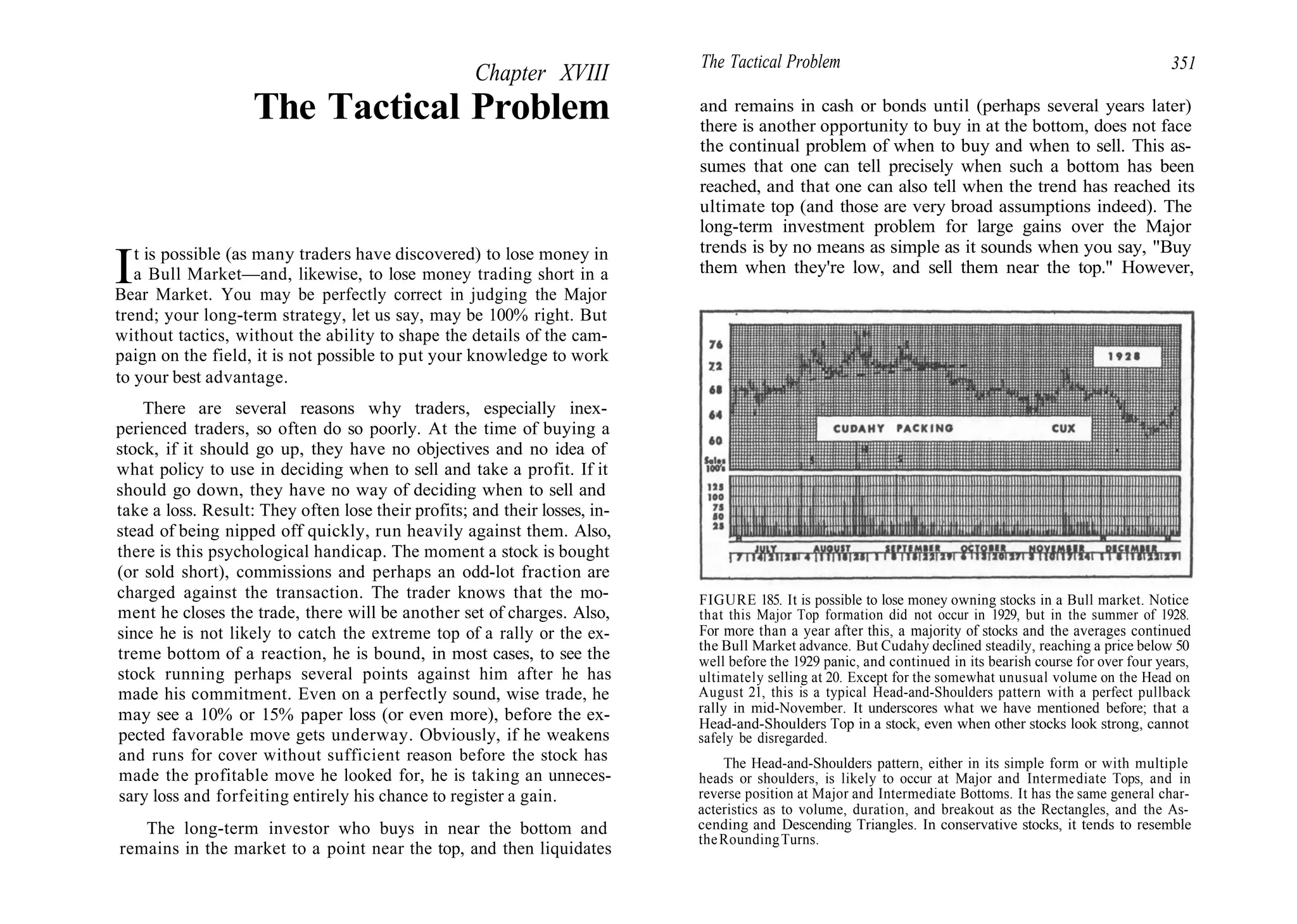

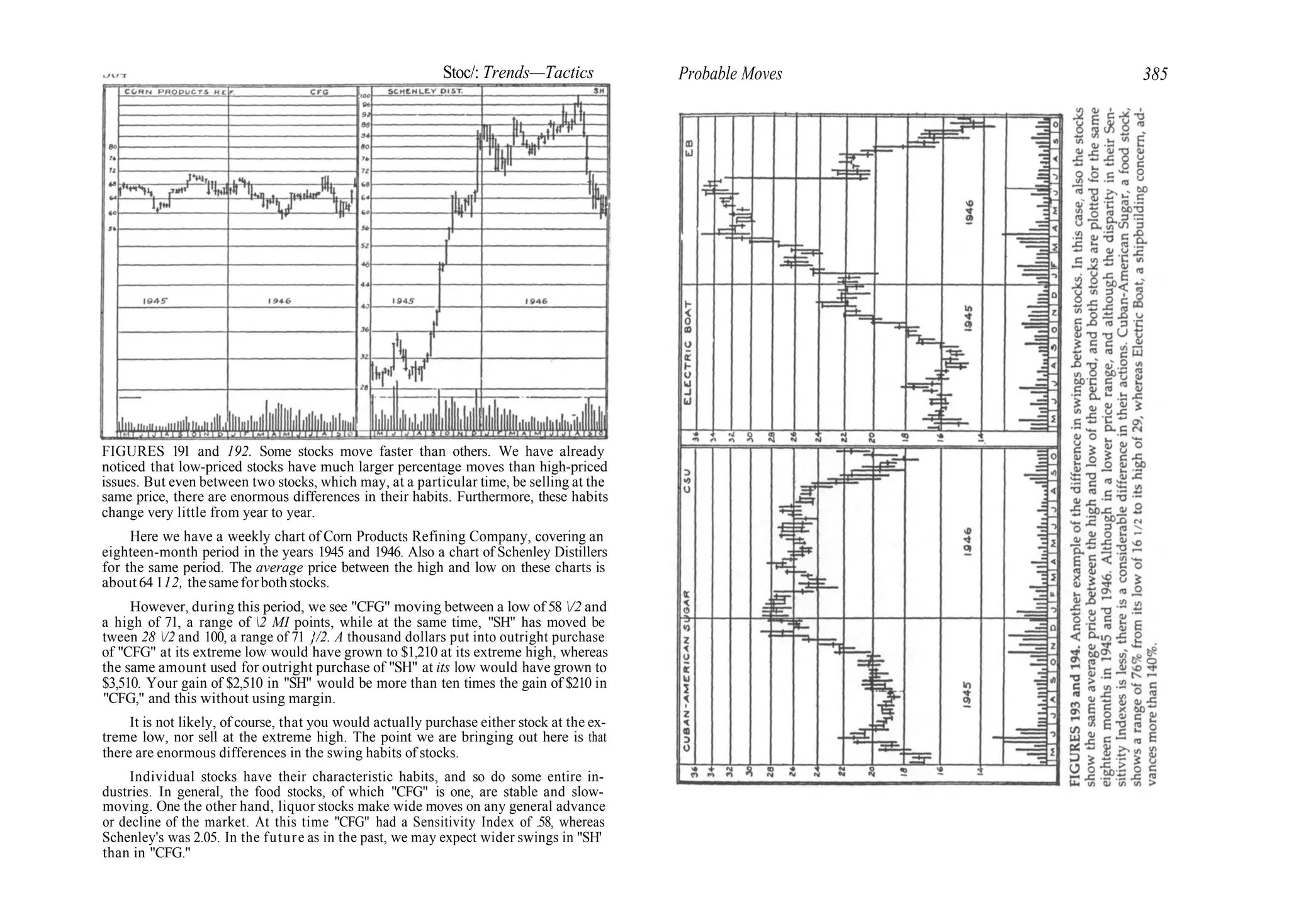

DIAGRAM 3 (Left). Here is a rising trend showing the basic trendline across two

bottoms, which we call the Red Trendline, and its parallel (indicated by a broken

line) through the top of the intervening peak. The parallel suggests the ap-

proximate objective of the next move if the stock continues in trend.

DIAGRAM 4 (Right). The same rising trend with the return line, which we call

the Blue Trendline, drawn through two tops. Broken line represents its parallel

through the intervening bottom. This Blue Parallel is useful in determining a

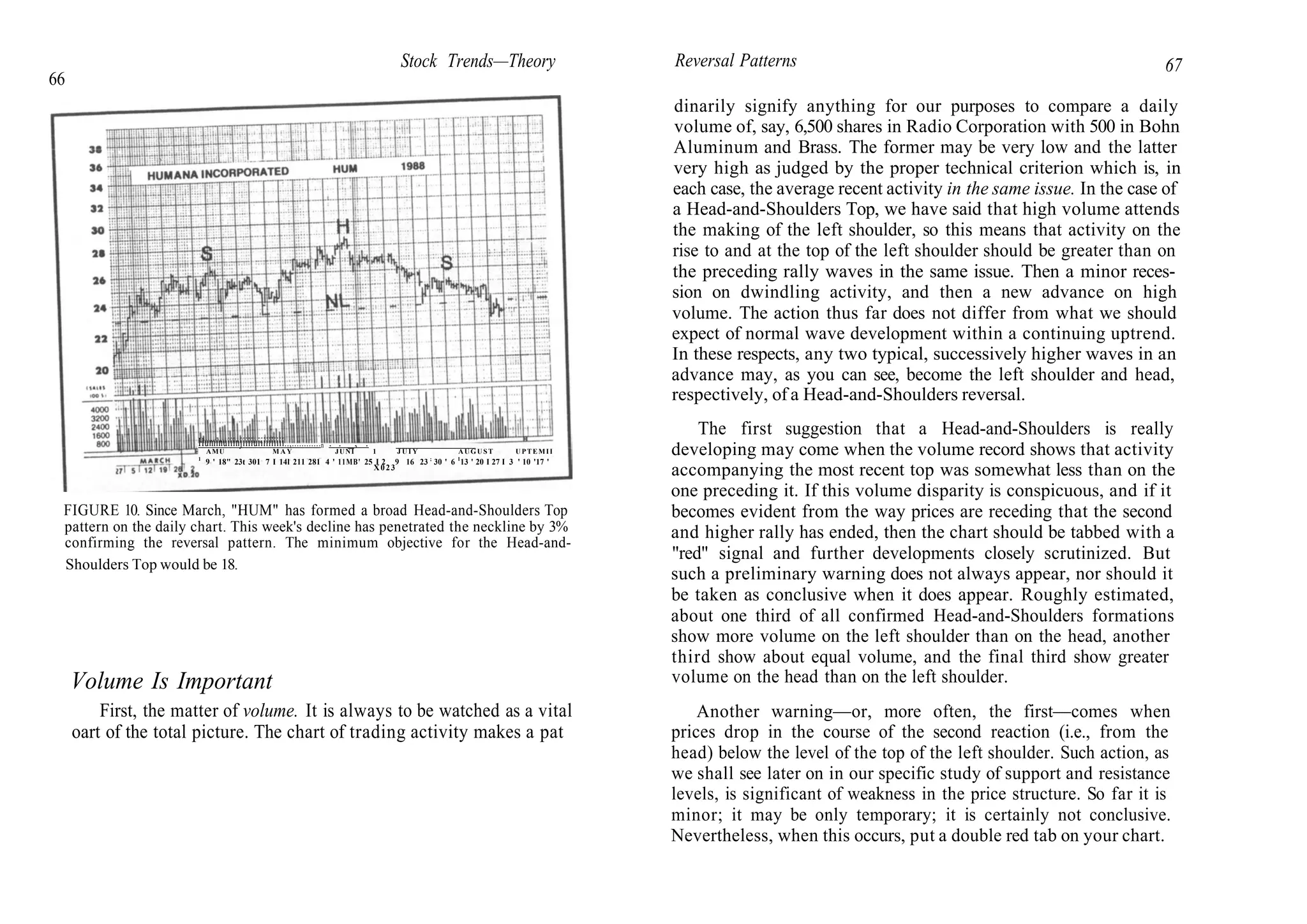

buying point, especially in trends of rapidly changing form when the stock may

not react to its basic trendline.

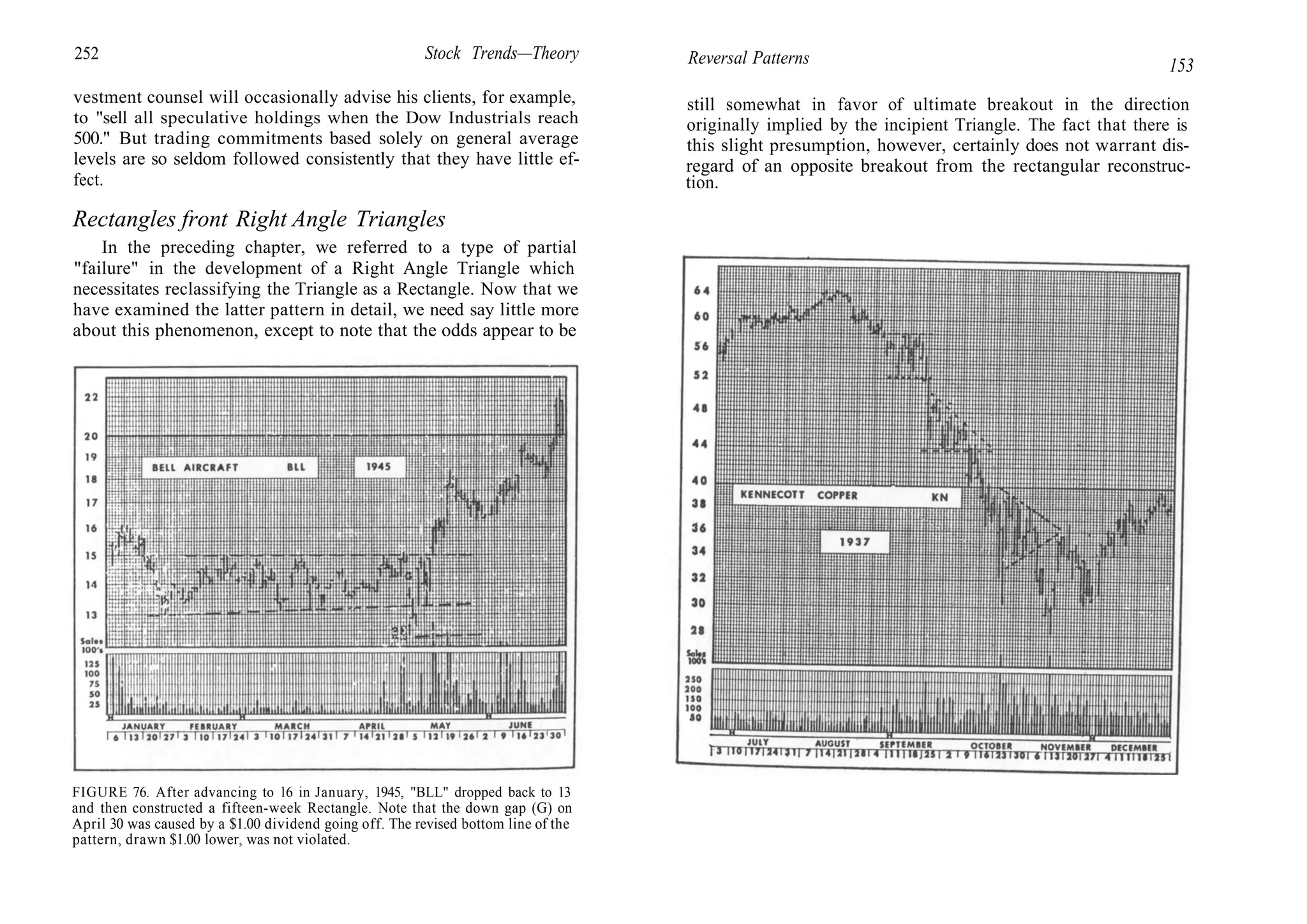

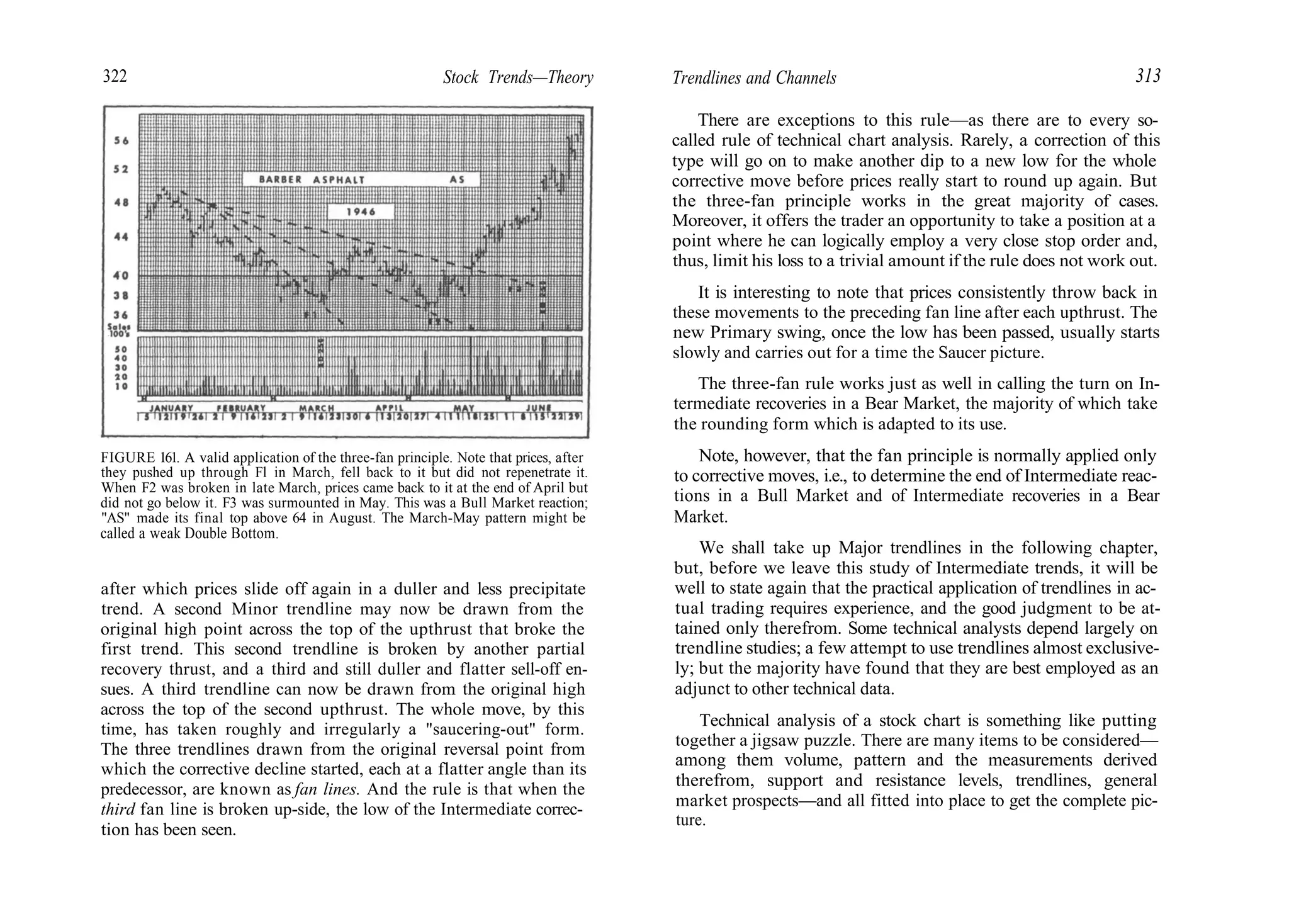

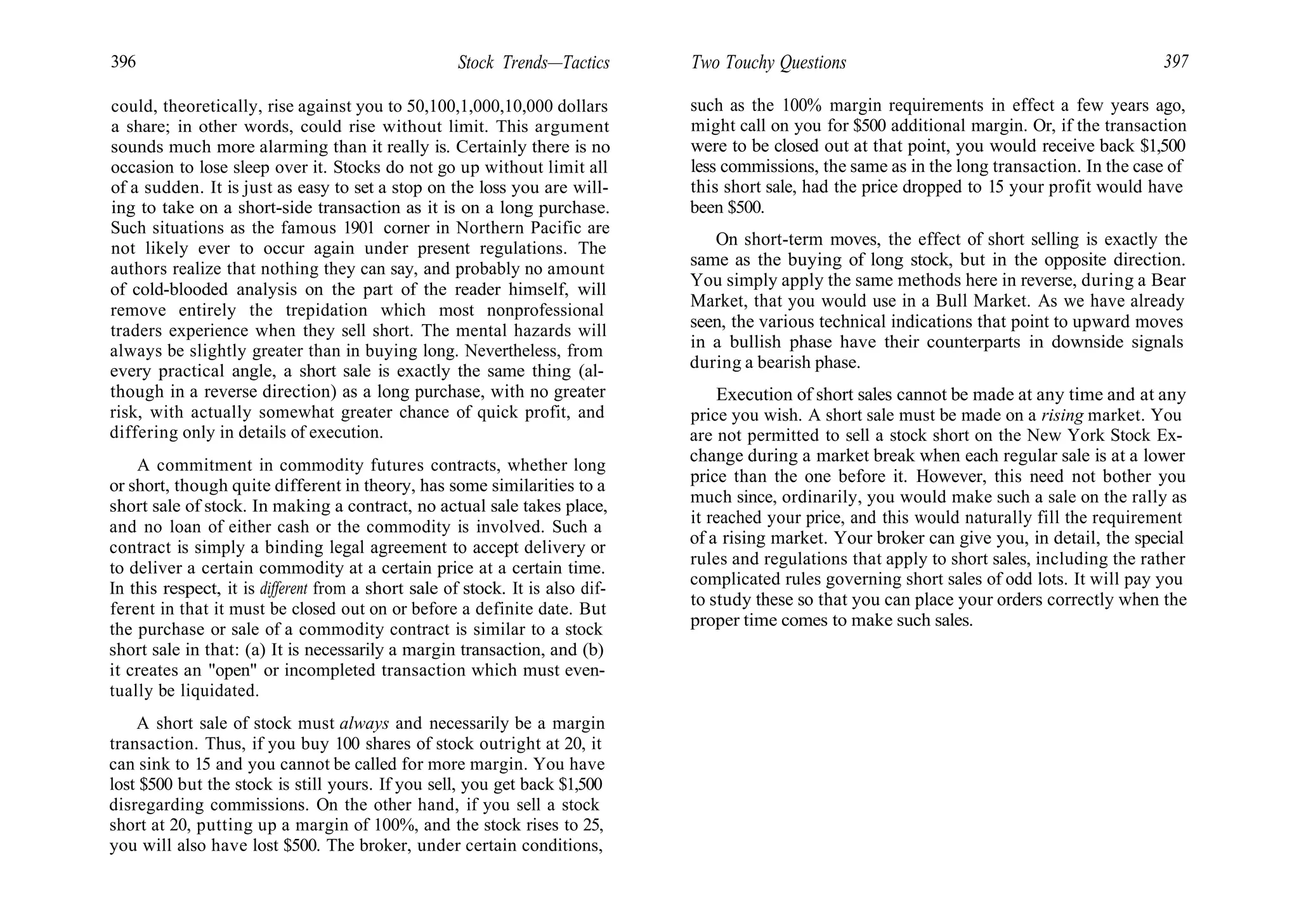

DIAGRAM 5 DIAGRAM 6

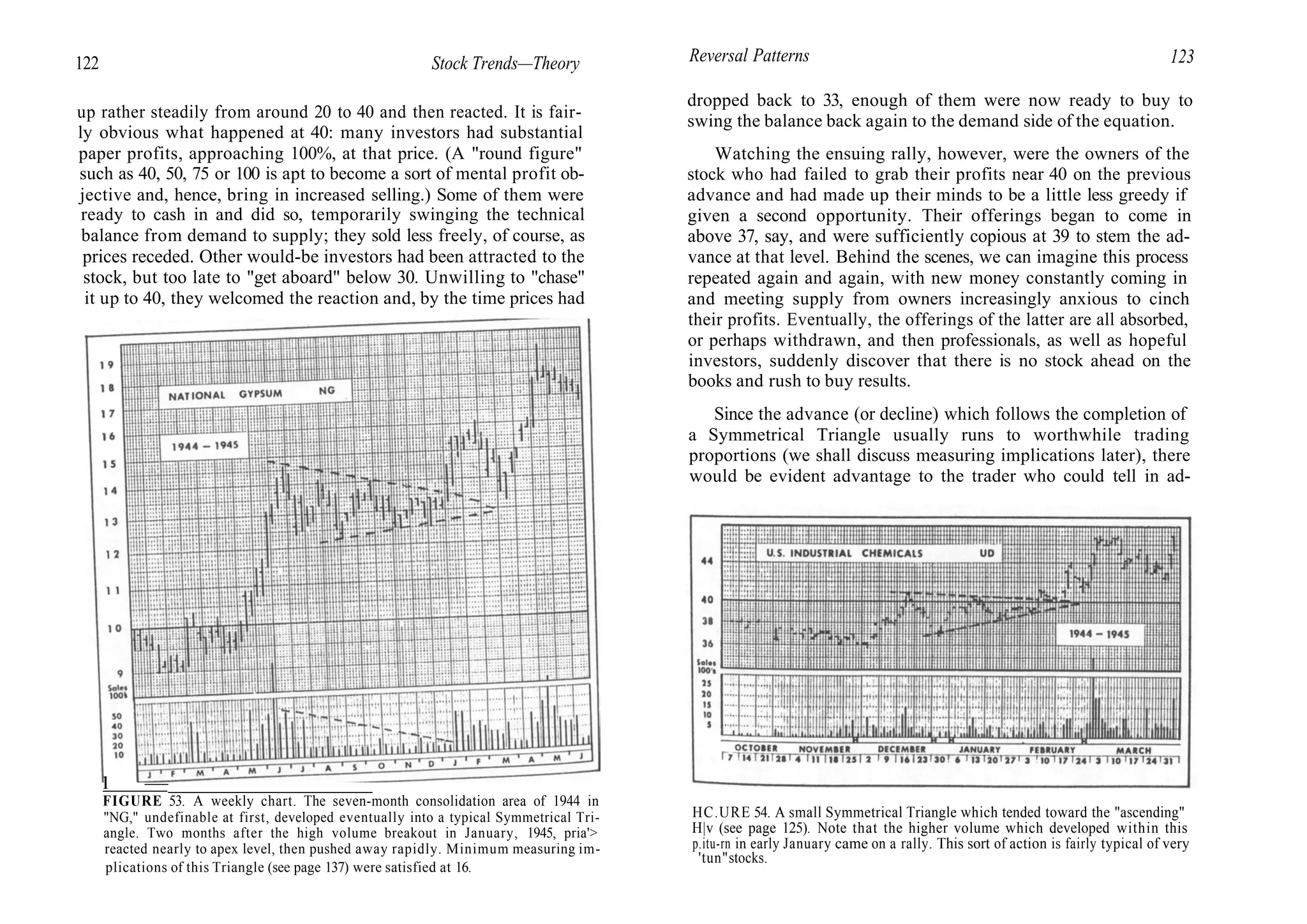

DIAGRAM 5 (Left). This is a declining trend showing the basic trendline across

two tops, which we call the Blue Trendline, and its parallel (indicated by a broken

line) through the bottom of the intervening decline. The parallel suggests the ap-

proximate objective of the next move if the stock continues in trend.

DIAGRAM 6 (Right). The same declining trend with the return line, which we

call the Red Trendline, drawn through two bottoms. Broken Line represents its

parallel through the intervening top. This Red Parallel is useful in determining a

point at which to make short sales, especially in trends of rapidly changing form

when the stock may not rally to its basic trendline.

Trendlines in Action 417

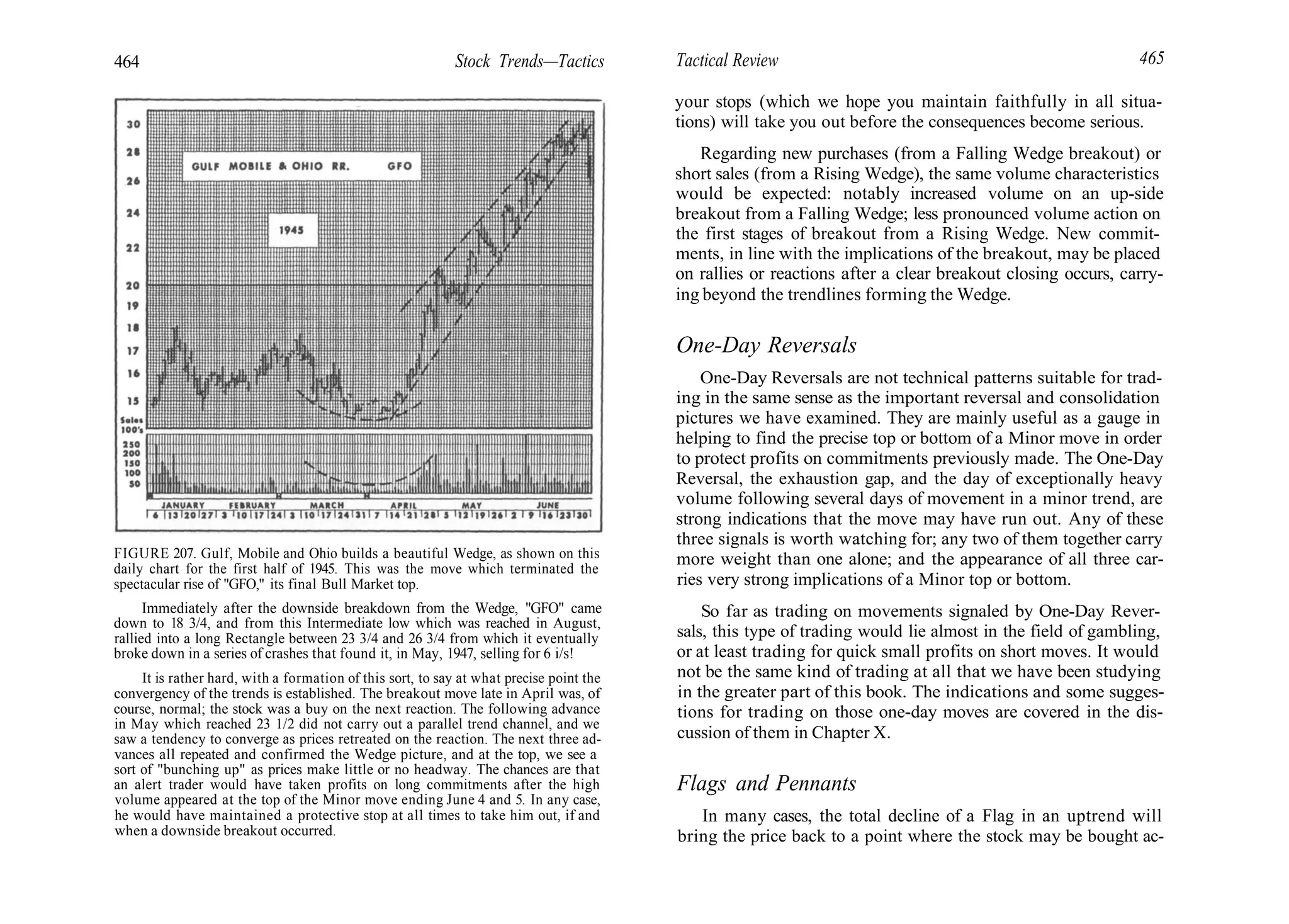

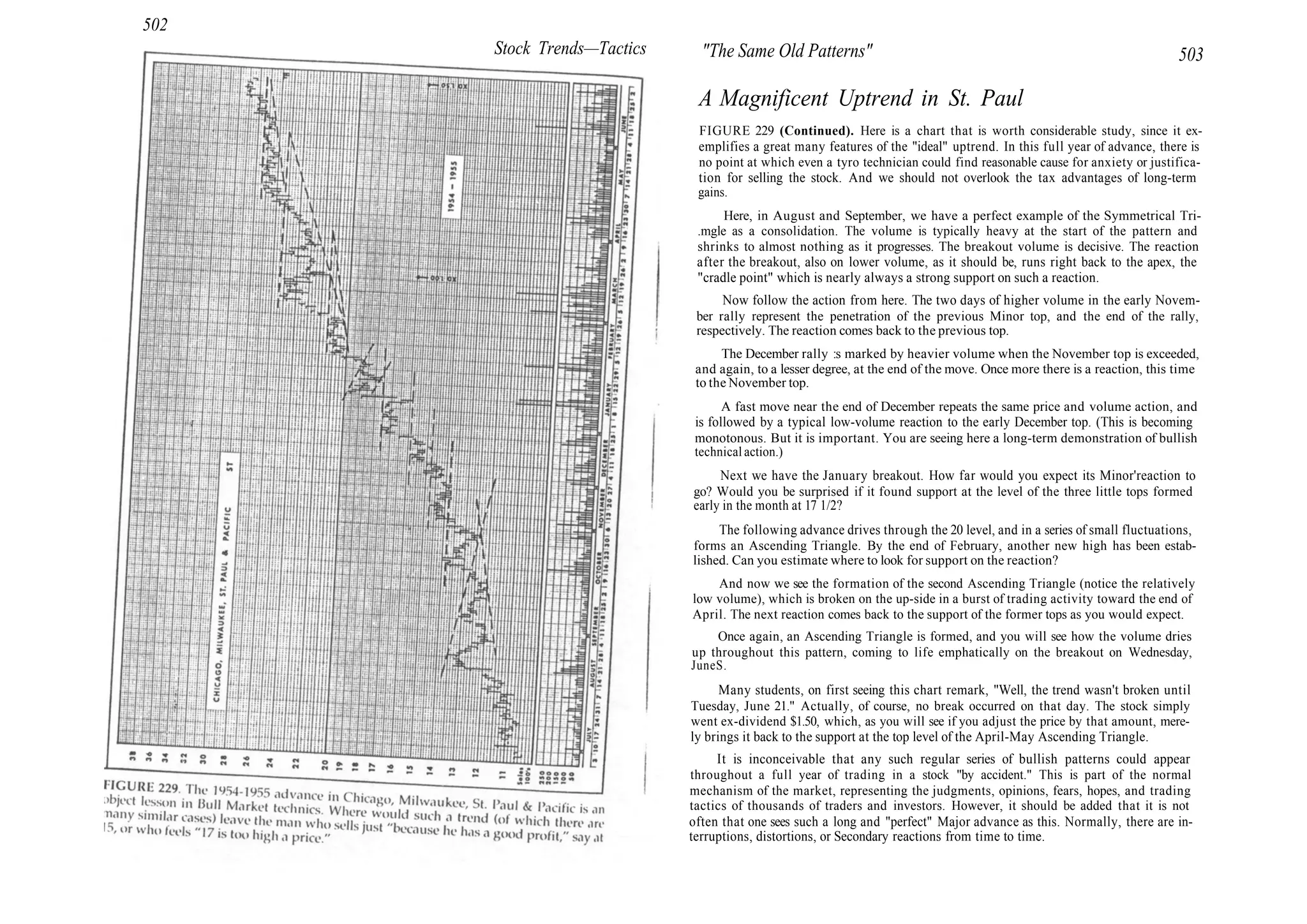

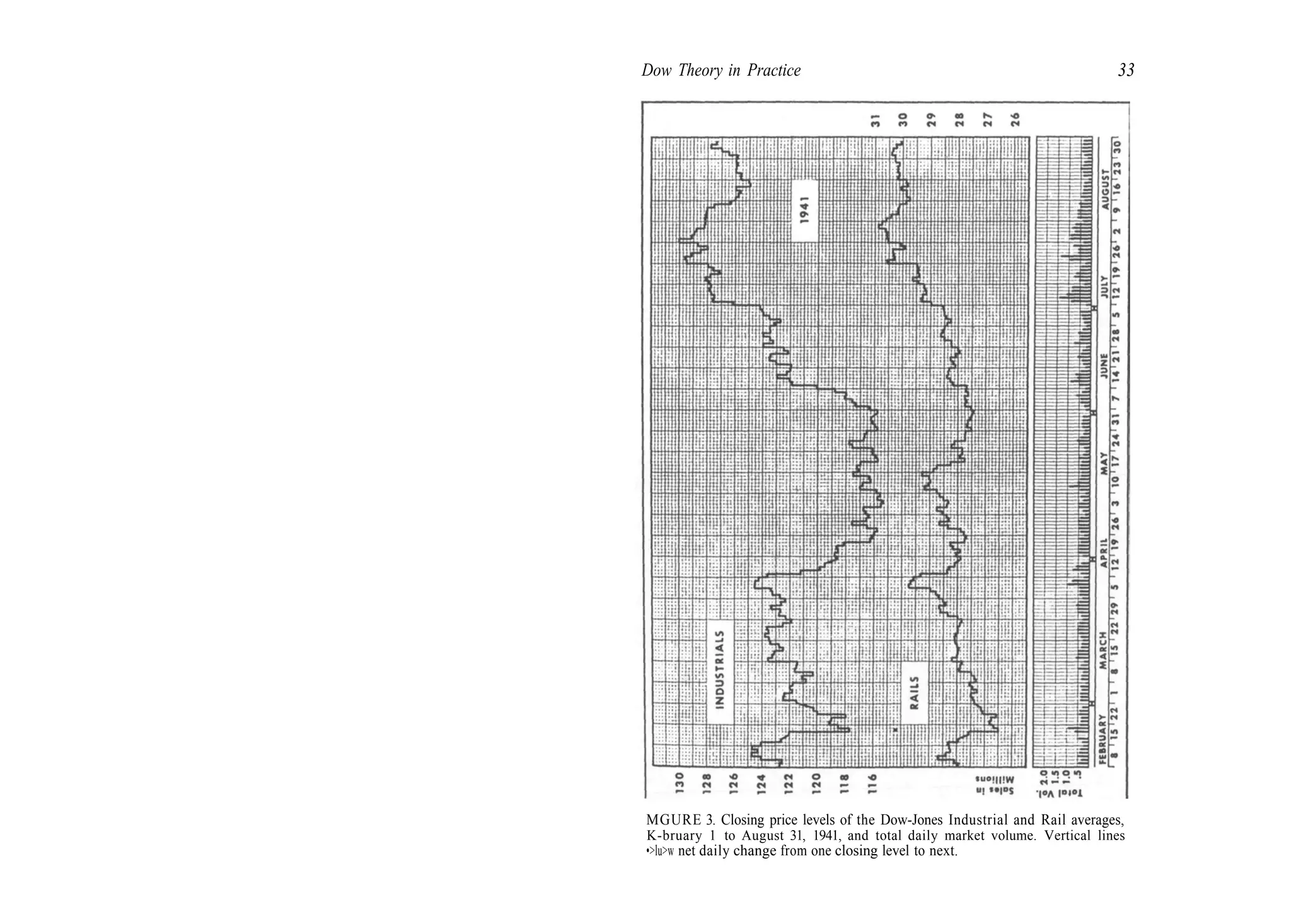

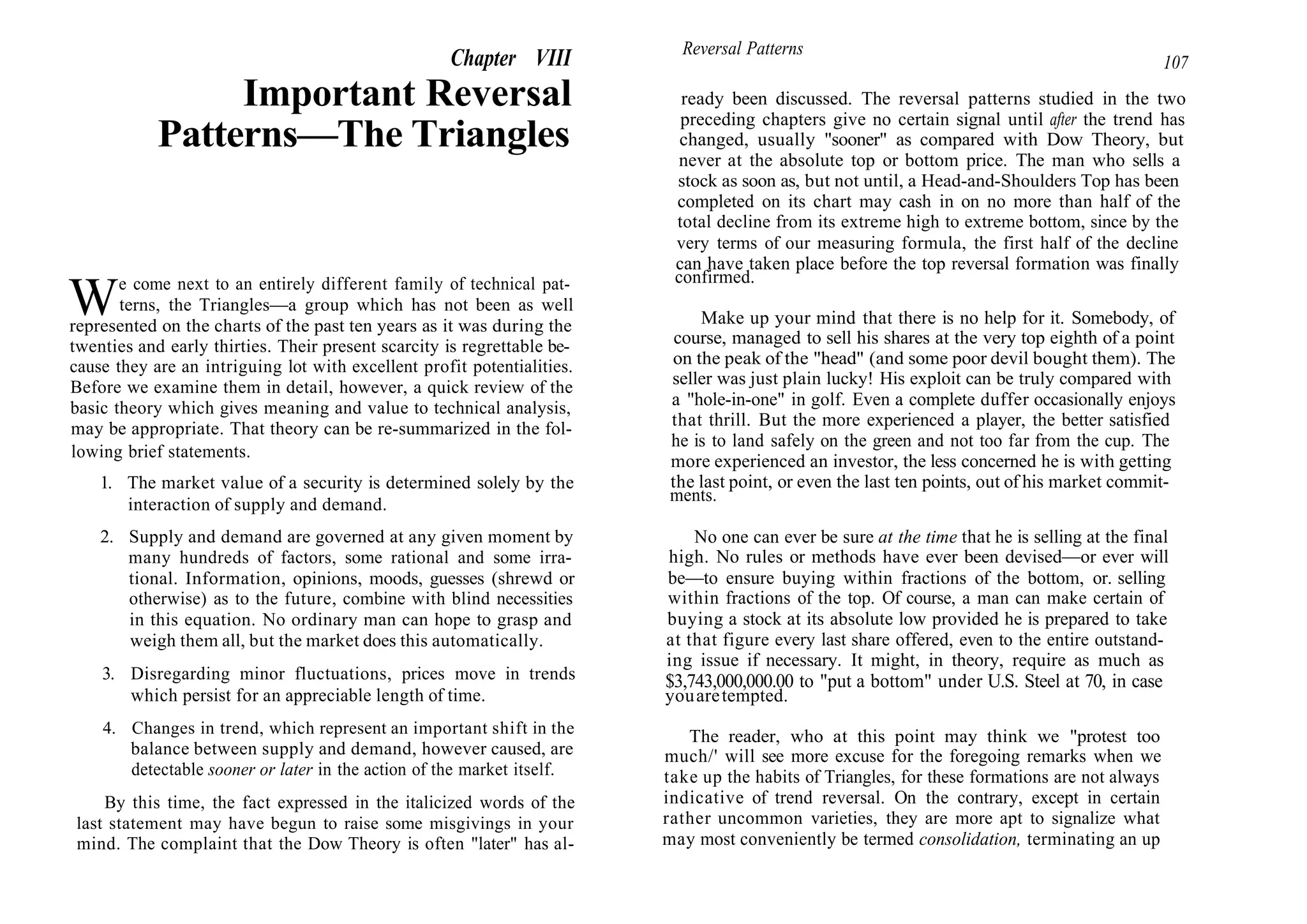

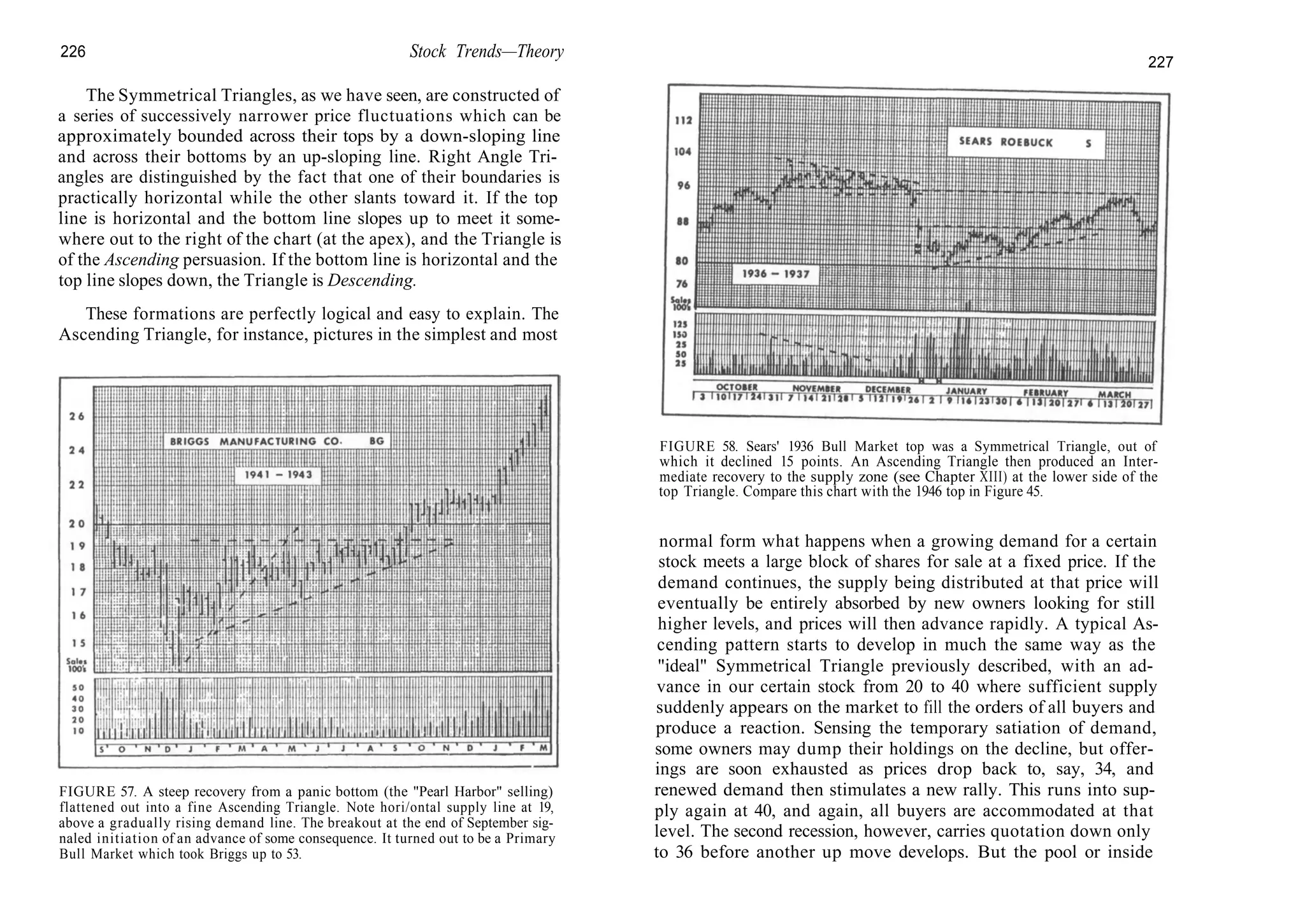

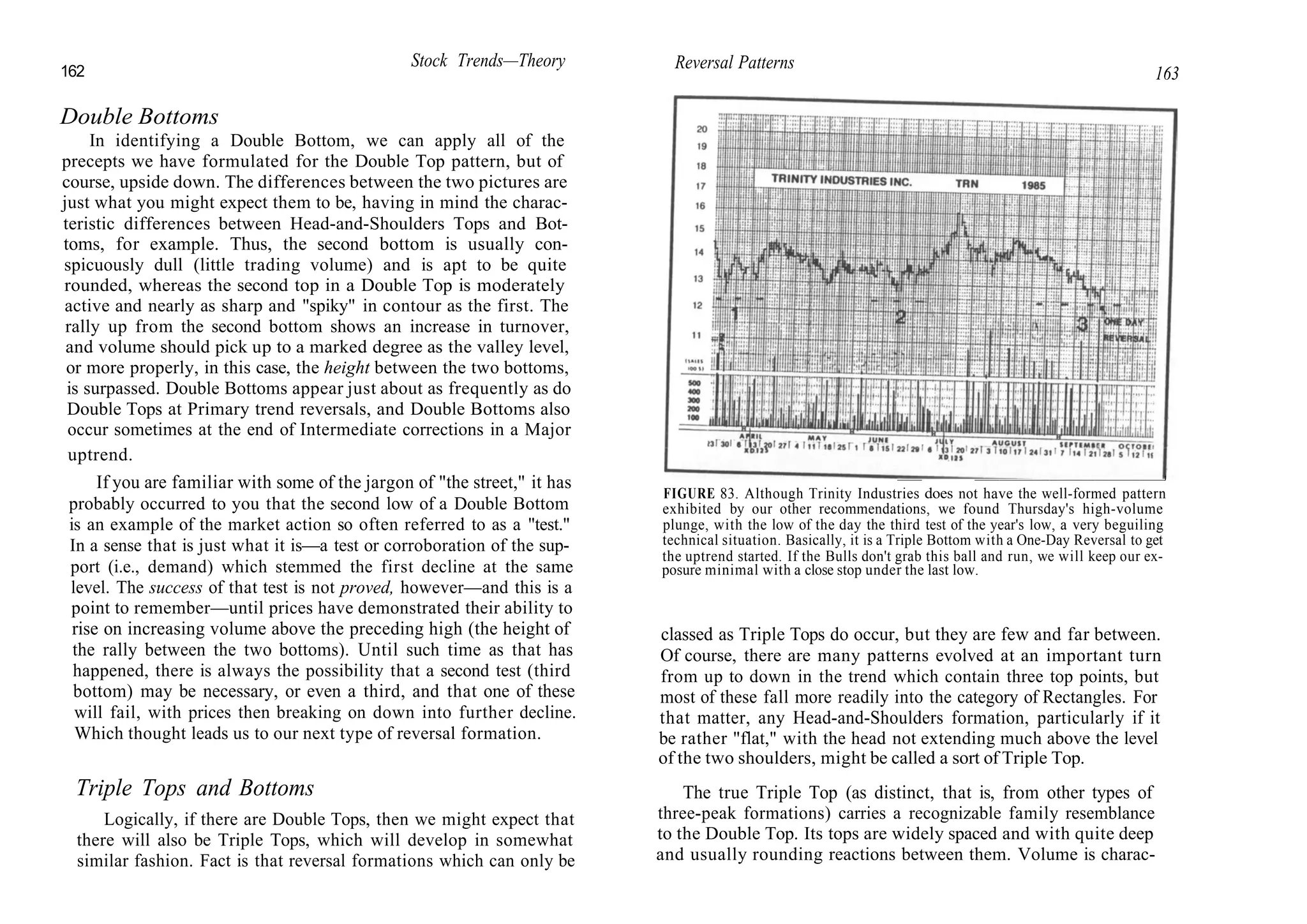

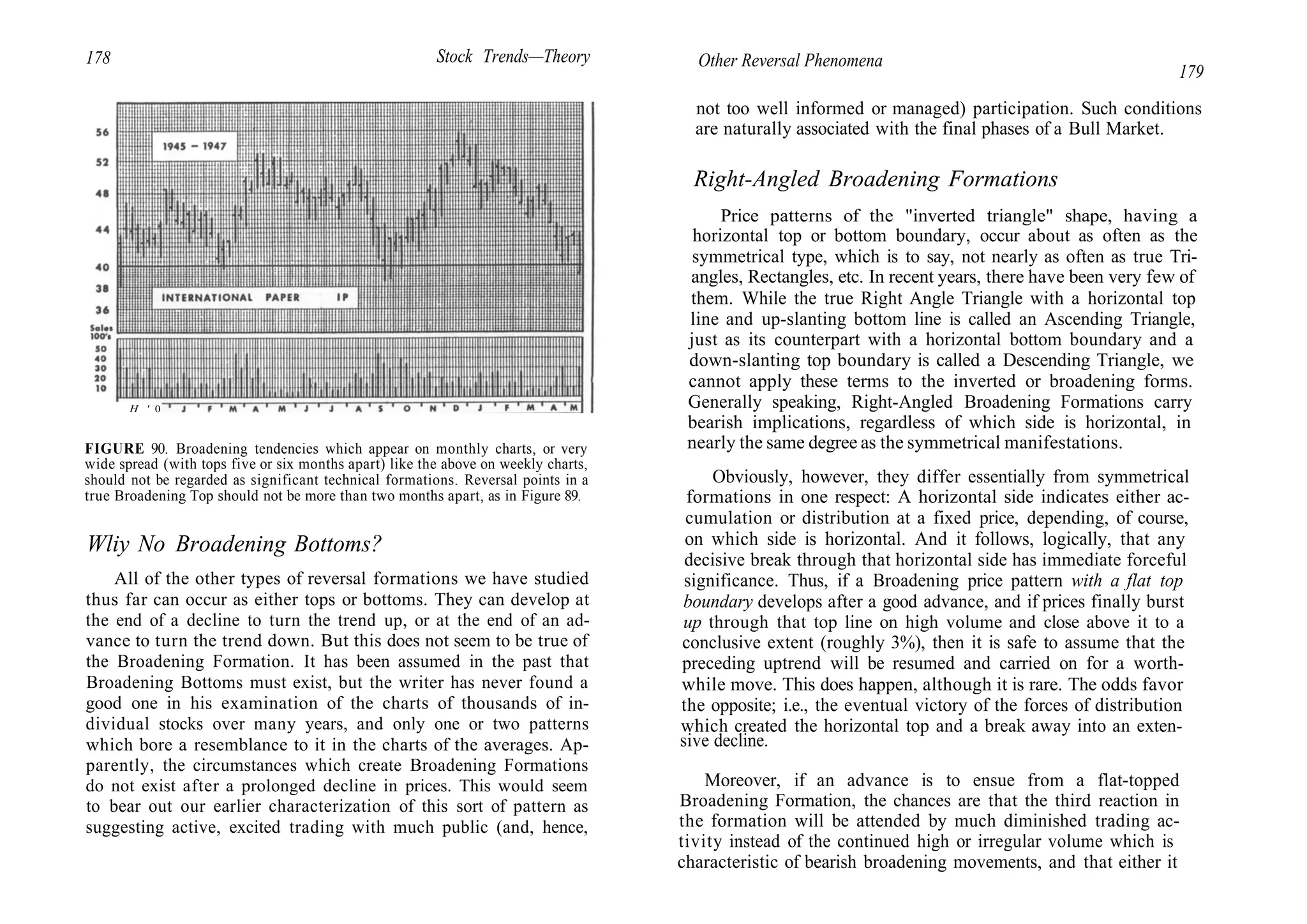

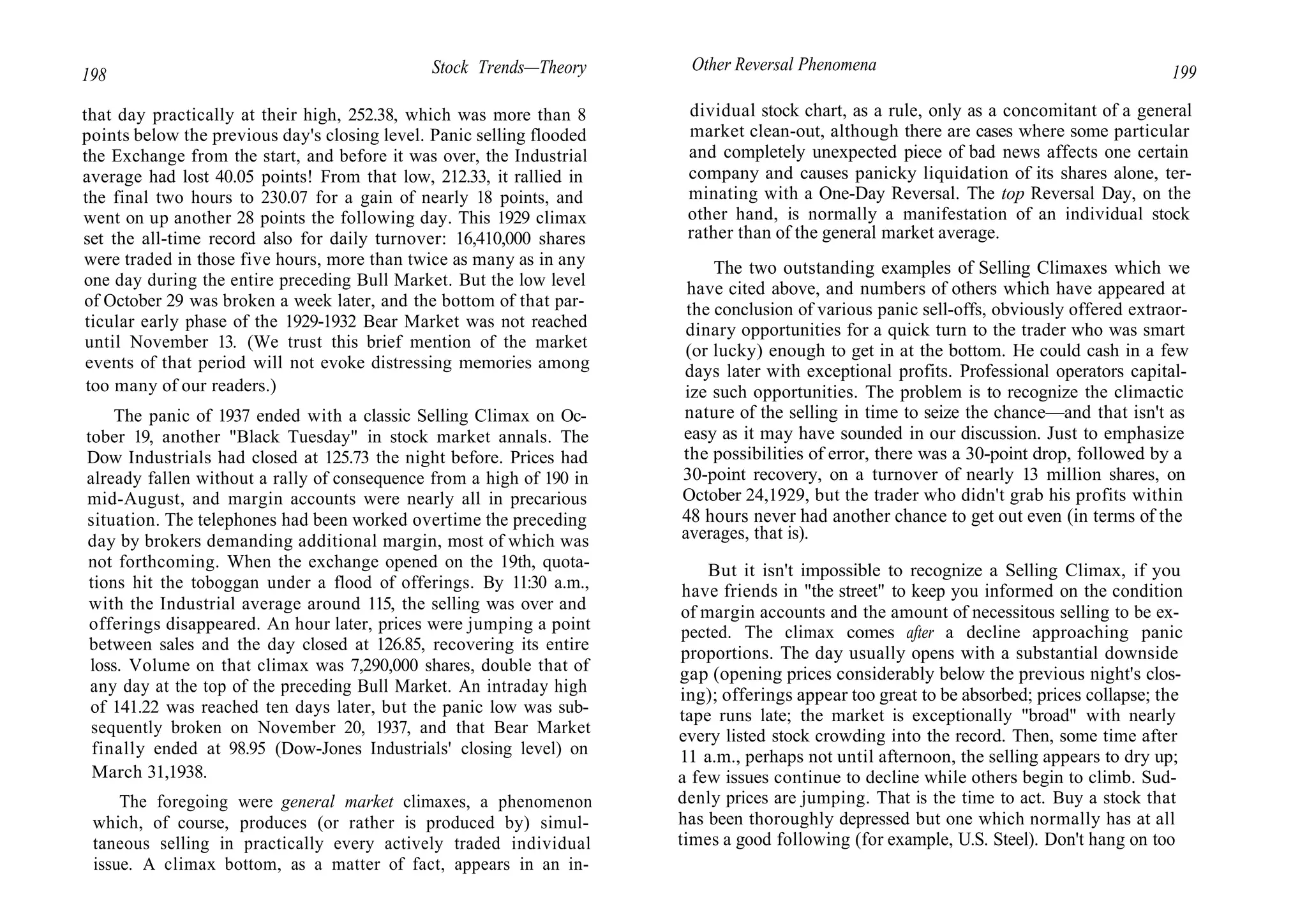

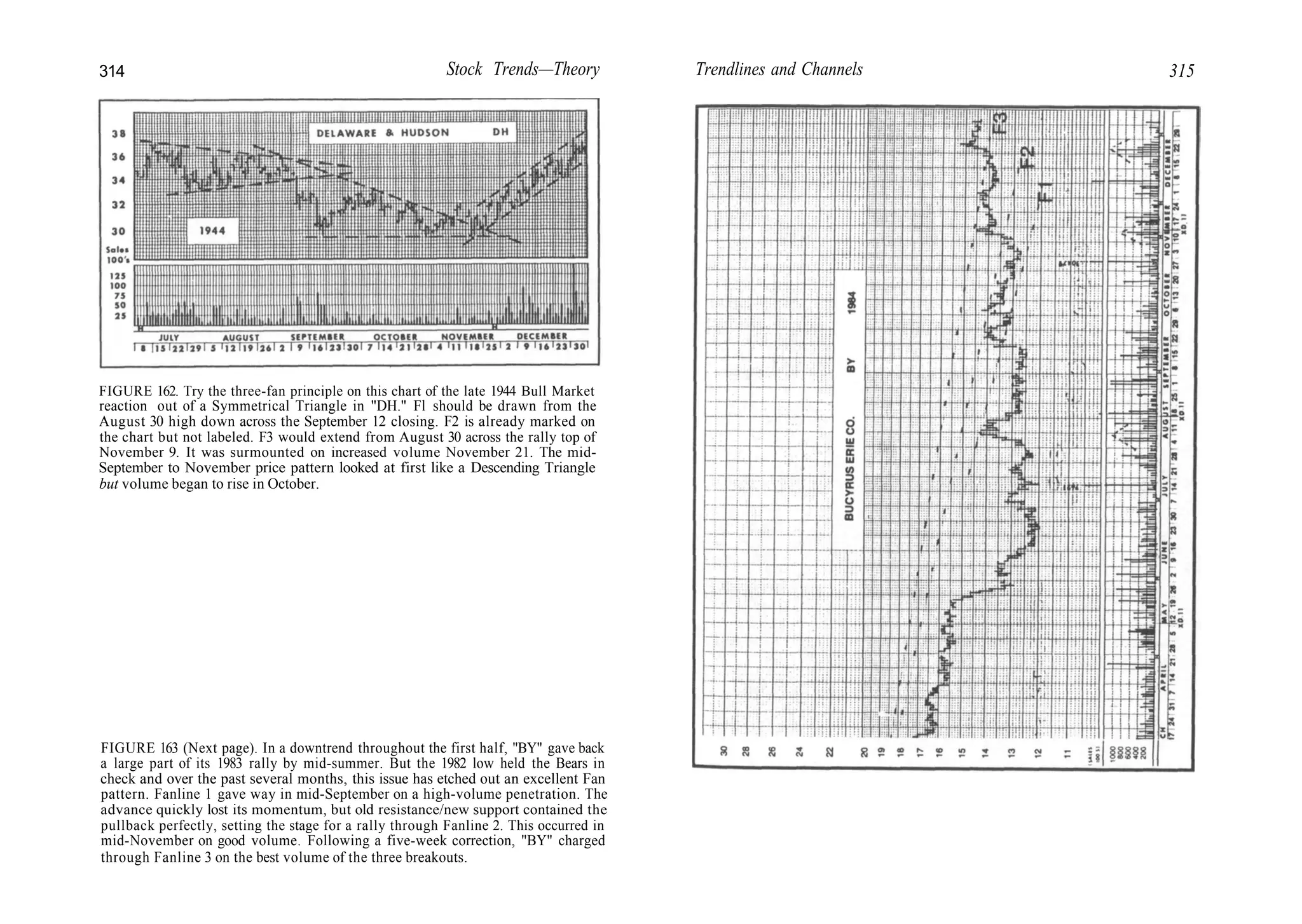

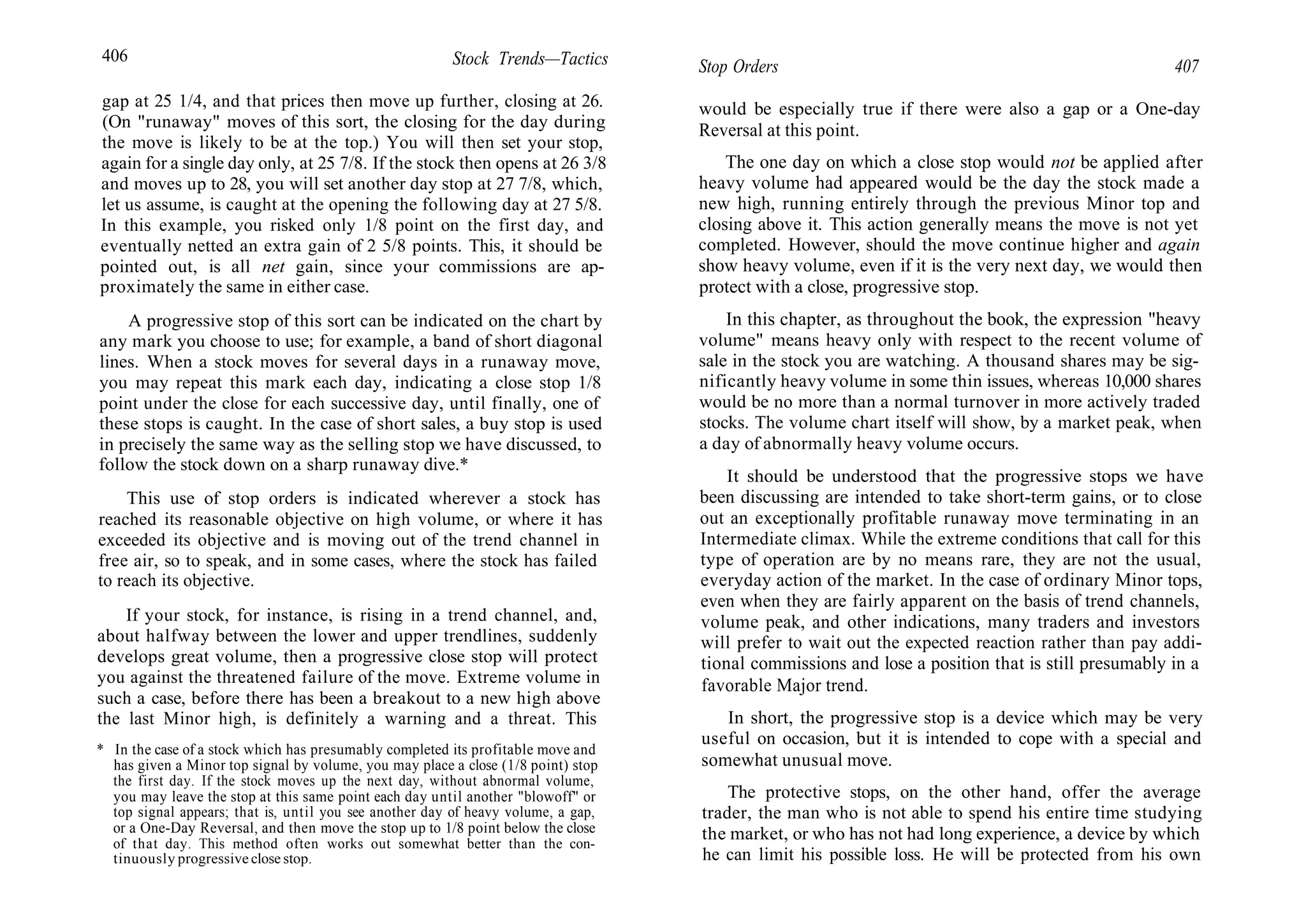

DIAGRAM 7. Simplified diagram of a stock chart showing trend action. Basic trendlines

are marked with heavy lines; return lines are marked lightly.

At the start, the stock declines in a parallel trend channel. Blue Trendline is basic here.

A short sale on a rally to the Red Parallel at point A will find its objective on the Blue Paral-

lel at B. Another short sale on the Red Parallel at C would be followed by failure to reach

the objective. Chances are good, however, that increased volume would develop at the

double bottom and give warning to get out of short commitments. The up-side penetration

of the basic Blue Trendline at E, alone, is not sufficient reason to reverse position and go

long. Trendlines set up during formation of the Rectangle would be marked in the regular

way, but are indicated here by broken lines to emphasize the pattern. Another short sale, if

tried on the sixth point of contact with the Rectangle at F, would be stopped out on the

breakout.

The trend is now rising, although we cannot yet draw a basic (Red) trendline. The first

buy would be made on a 40-50% correction of the breakout move from the Rectangle, or on

ti return to the top (support) level at H.

A trendline would be drawn to the first bottom established in the Triangle. This is not

shown, as it would ultimately be replaced by the line shown through the outermost point in

the Triangle. We have indicated by broken lines the trendlines set up during the formation

of the pattern.

The objective of the breakout move from the Triangle would be the Red Parallel to our

now rising basic trendline. This objective is reached at J. A return line (Blue) would be

drawn from the first reversal top of the Triangle at G through the top of the breakout move

at ], and the parallel to this through point I would indicate about where to make the next

purchase. As a matter of fact, the stock does not actually get back to that point; in practice,

the purchase would probably be made at K on the basis of a 40-50% correction, or on a reac-

tion to the support level G.

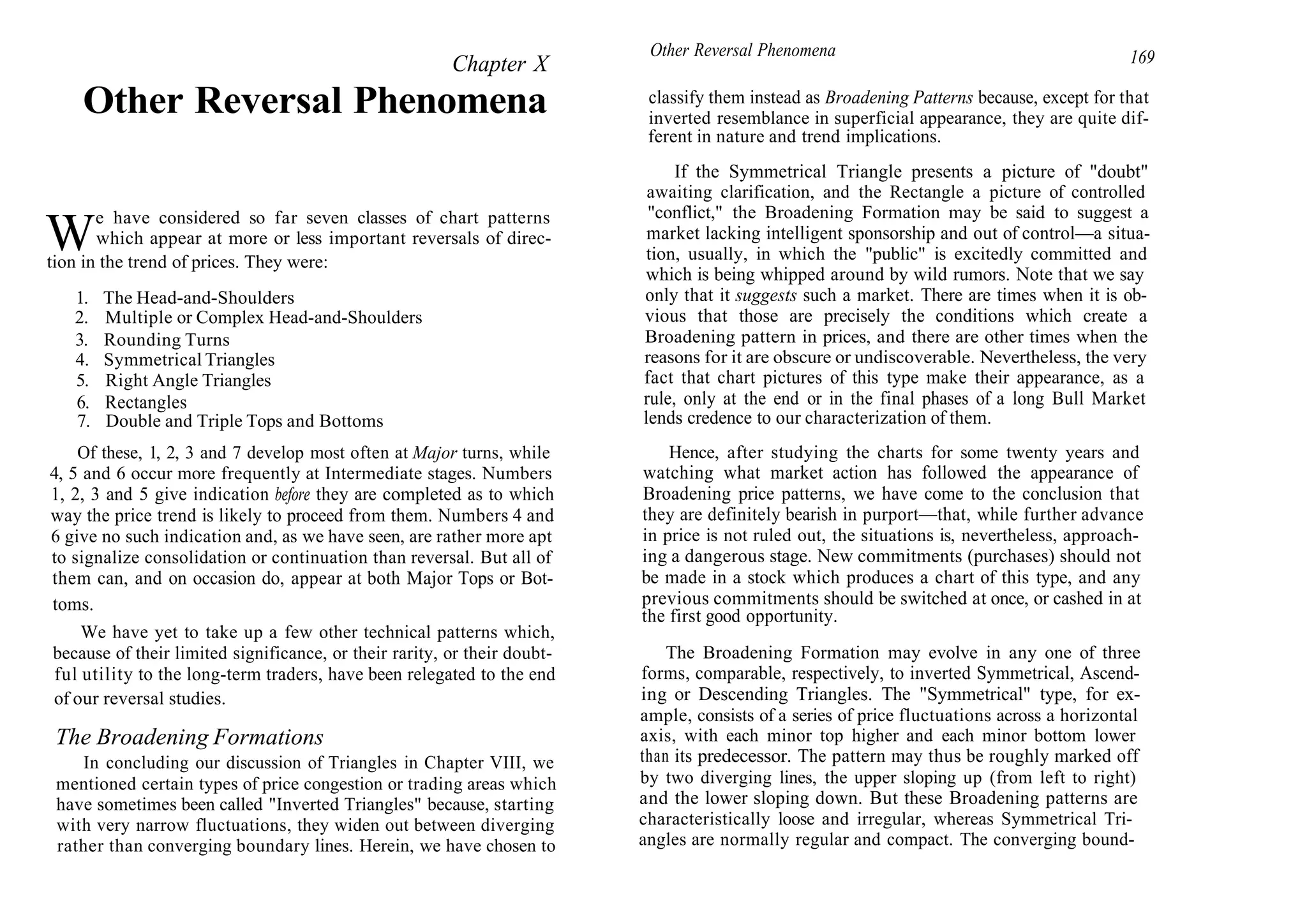

The subsequent upward move would not carry through to the Red Parallel marked W.

However, the alarm would probably be sounded clearly by a day of heavy volume, a One-

D.iy Reversal, or a gap. Since the trend is now obviously convergent, no further purchases

would be considered. The next move fails to make such headway and falls far short of the

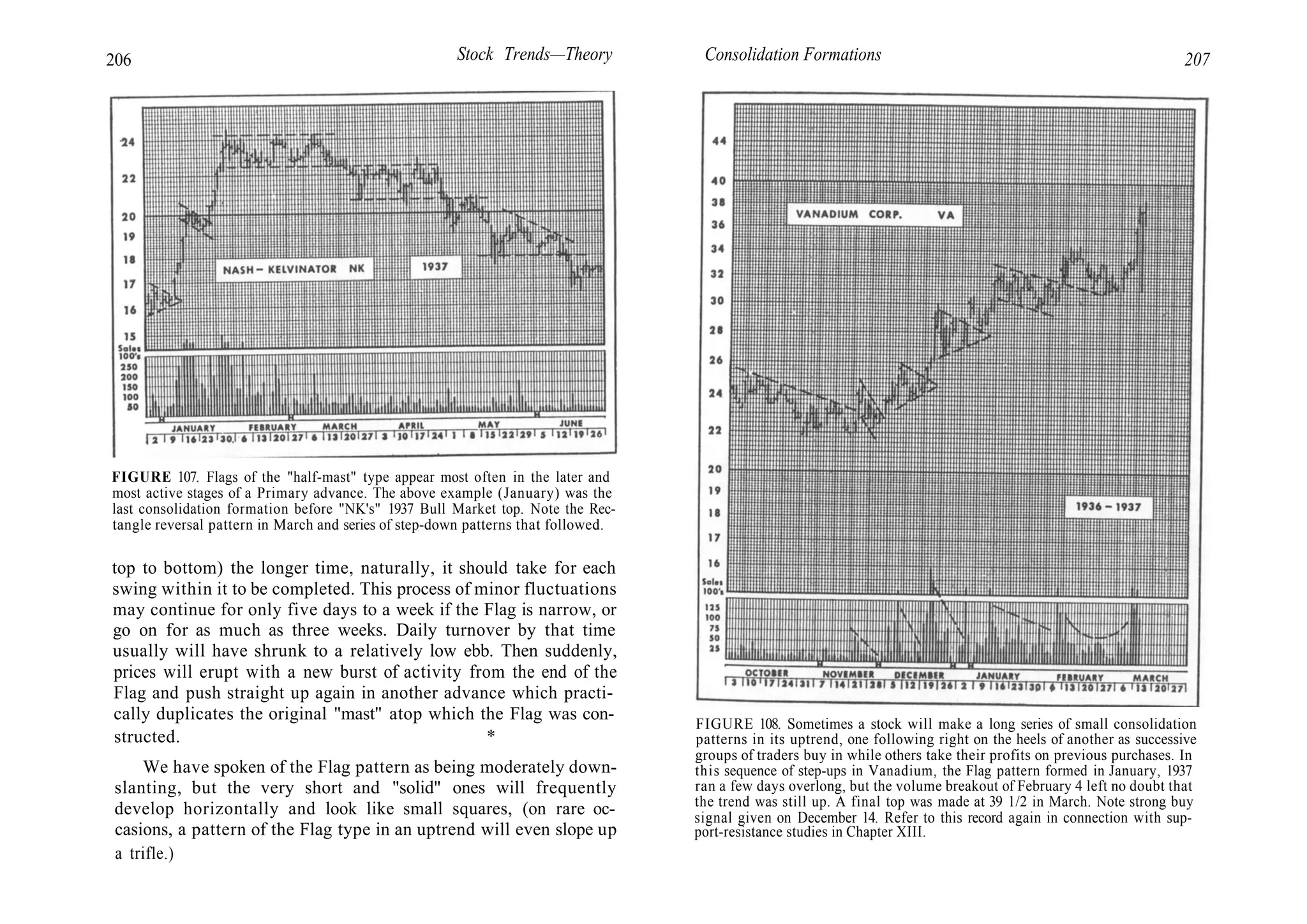

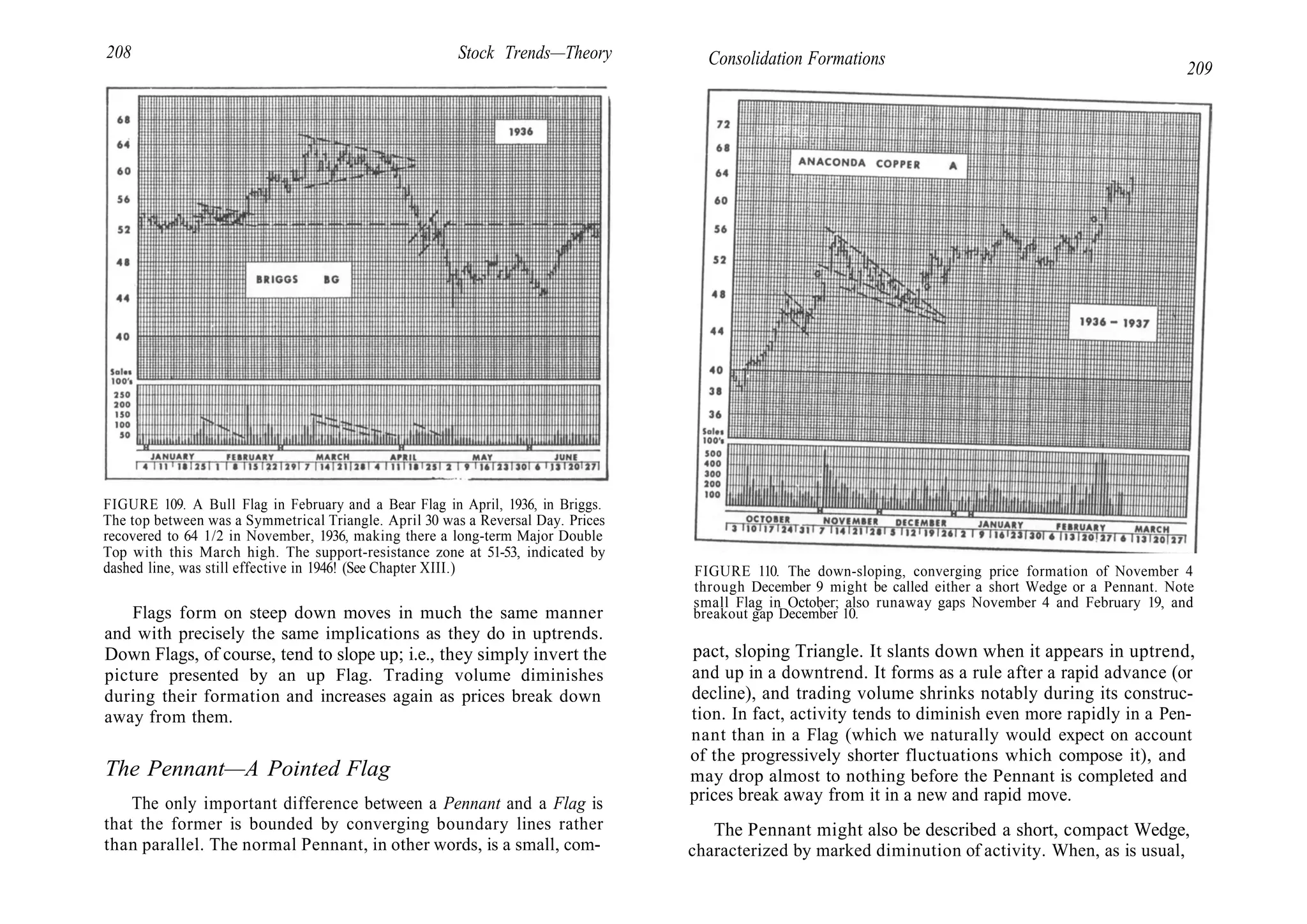

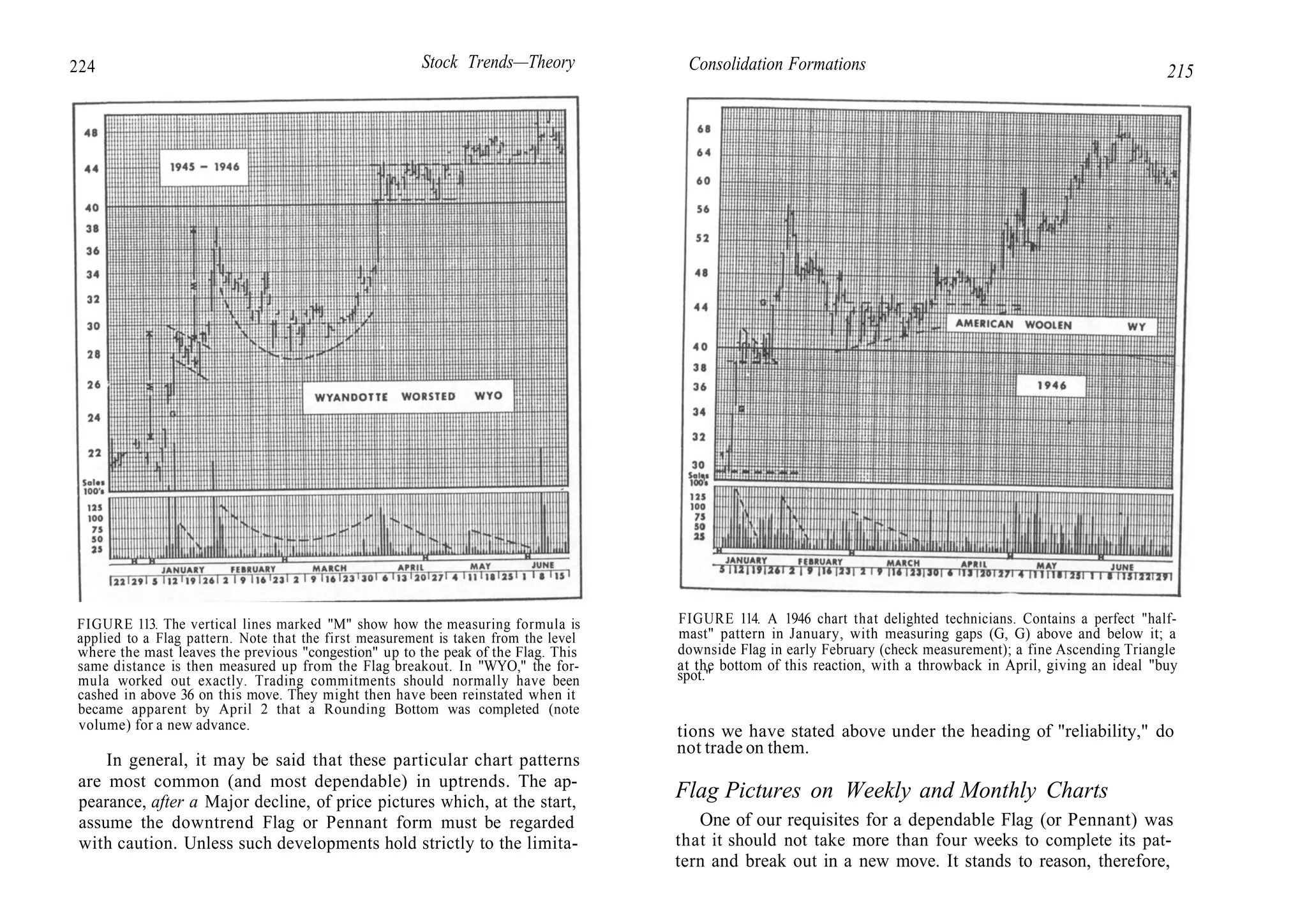

objective set by the Red Parallel marked Y. Soon after, the Wedge breaks out downside.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/robertd-231024104721-45c19745/75/Robert-D-Edwards-John-Magee-Technical-Analysis-Of-Stock-Trends-pdf-209-2048.jpg)