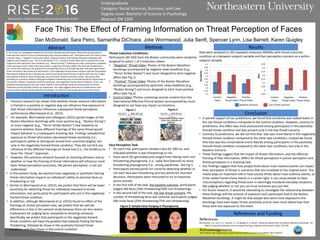

This study investigated how framing threatening information influences subsequent threat perception of faces. Participants viewed either a neutral video, a negatively framed video about the Boston Marathon bombings, or a positively framed video. They then completed a face perception task where they judged faces as threatening or non-threatening. The researchers predicted lower sensitivity but higher bias towards threat for those who viewed threatening videos, especially with negative framing. Preliminary results found lower sensitivity for threat detection in the threat video conditions compared to control, and an even lower sensitivity with positive rather than negative framing. Contrary to predictions, bias was less conservative in the positive framing condition only in the baseline scenario. The study suggests framing of mass violence events can impact unrelated threat perception