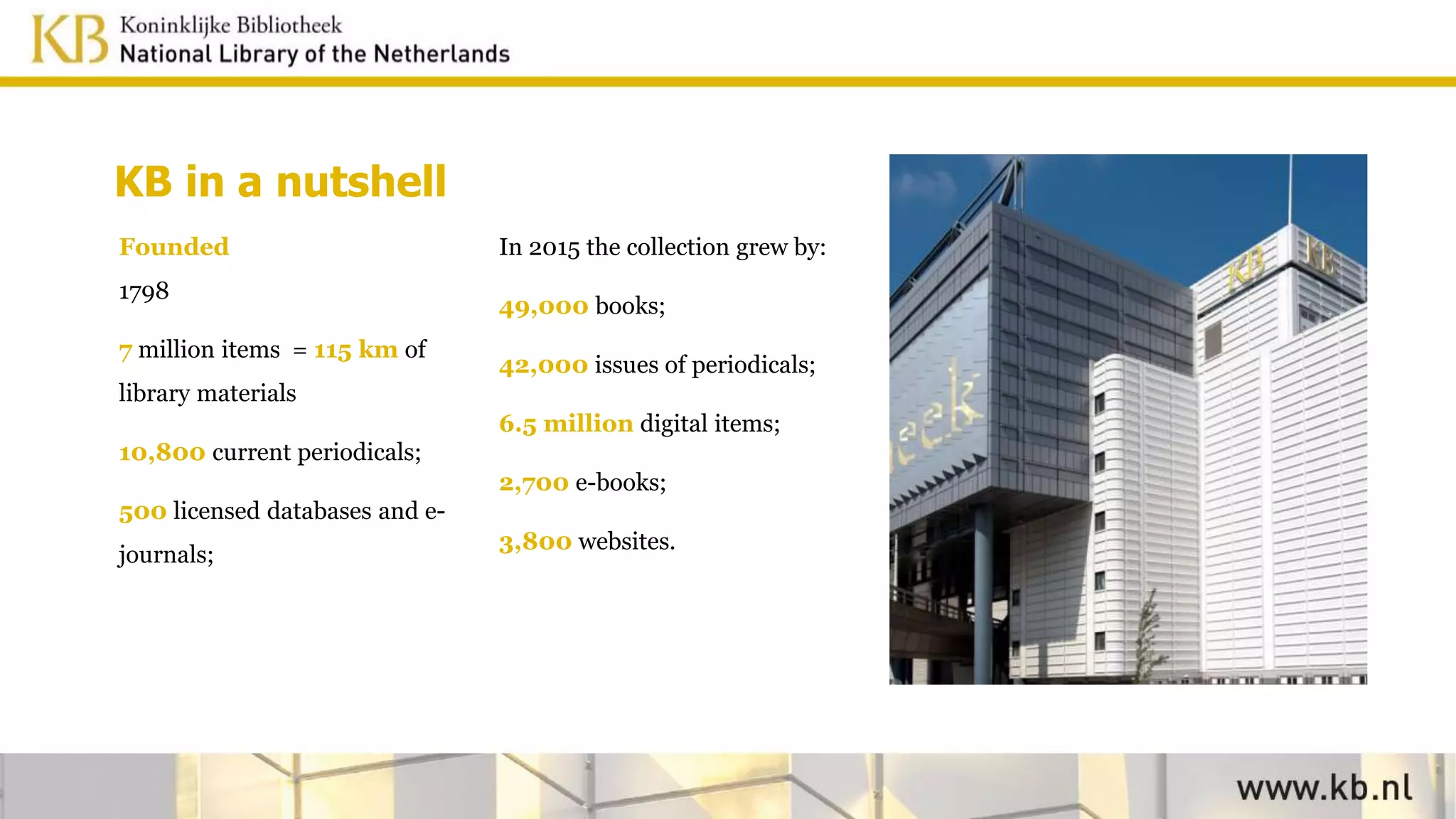

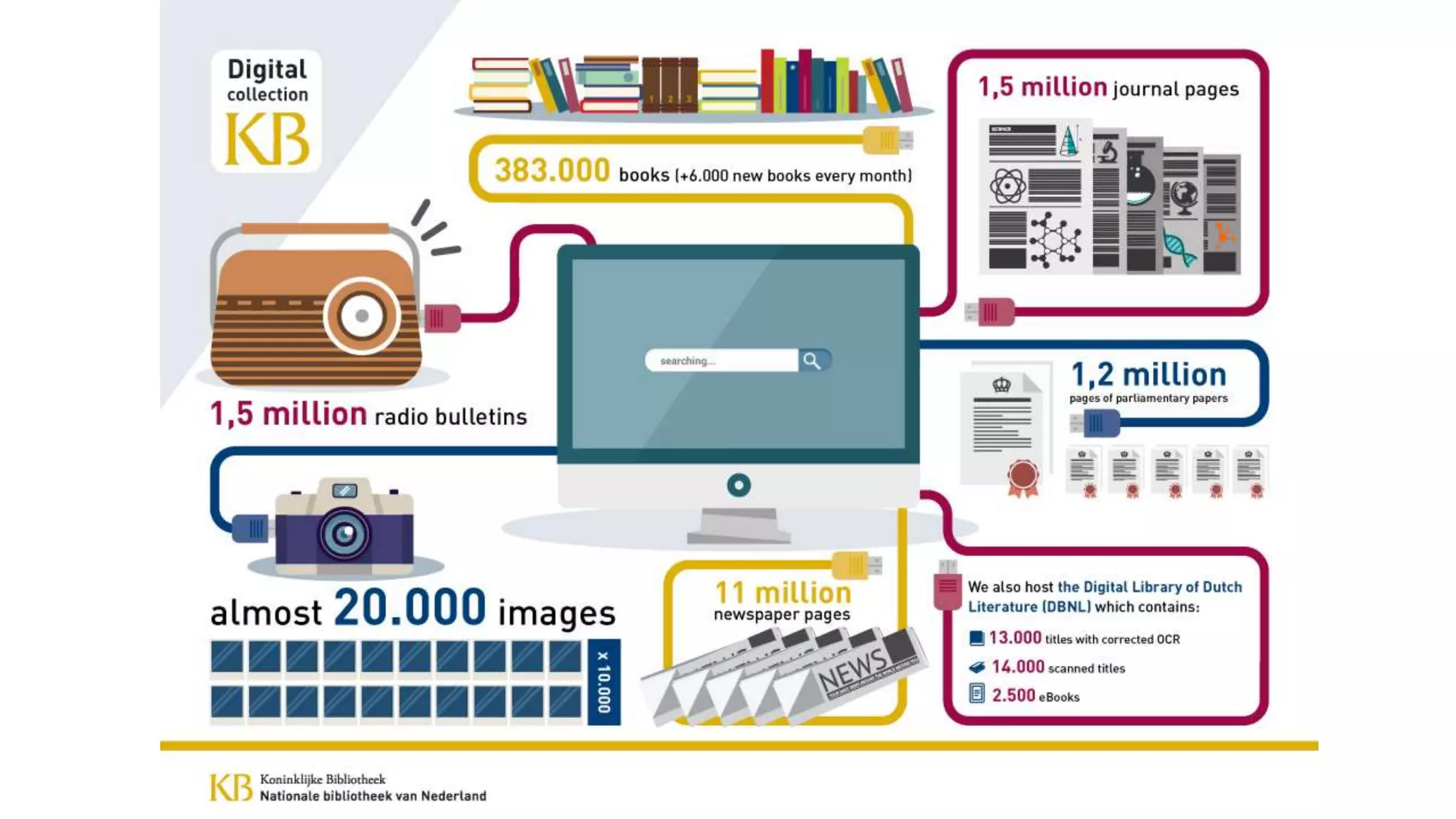

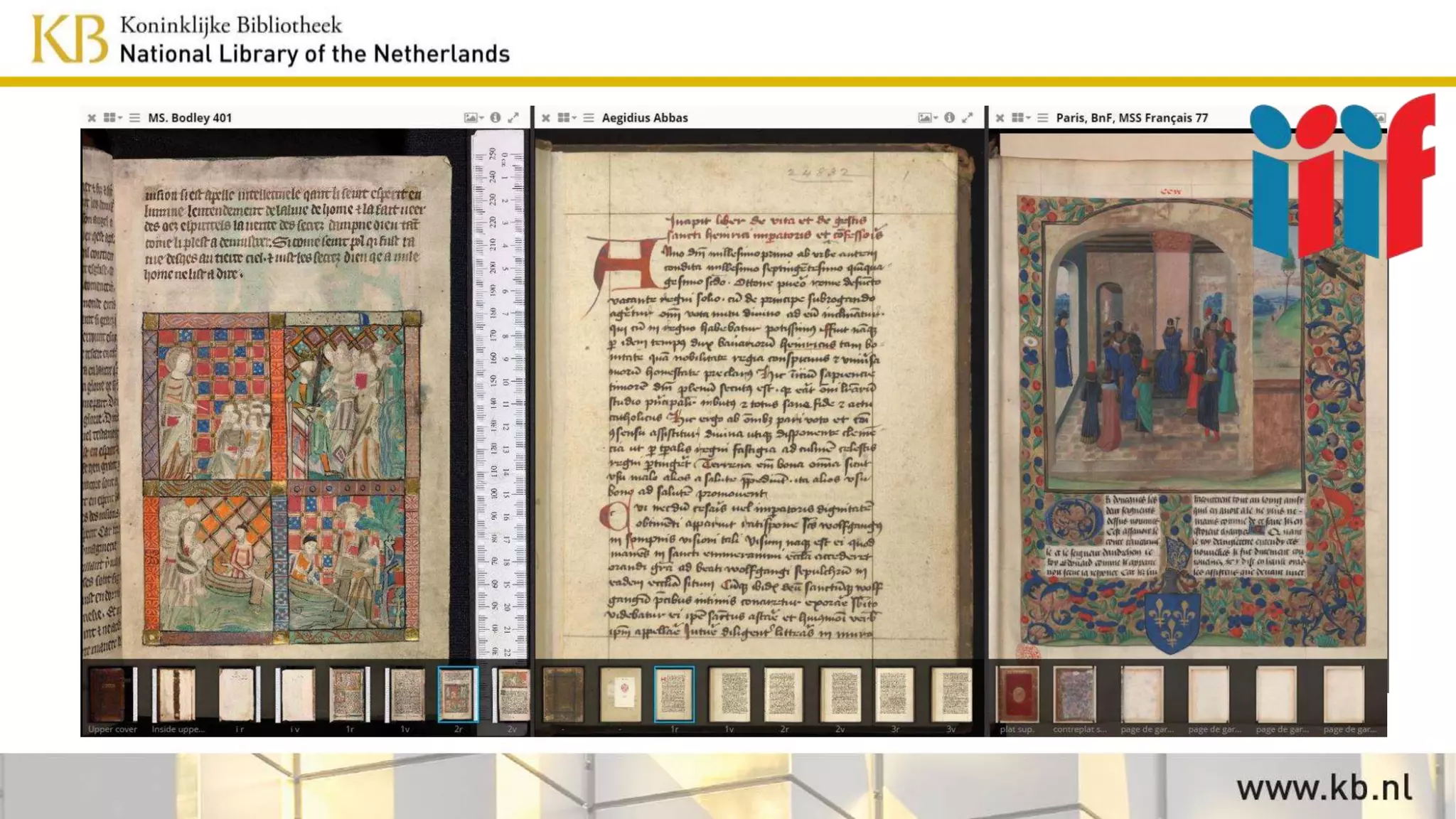

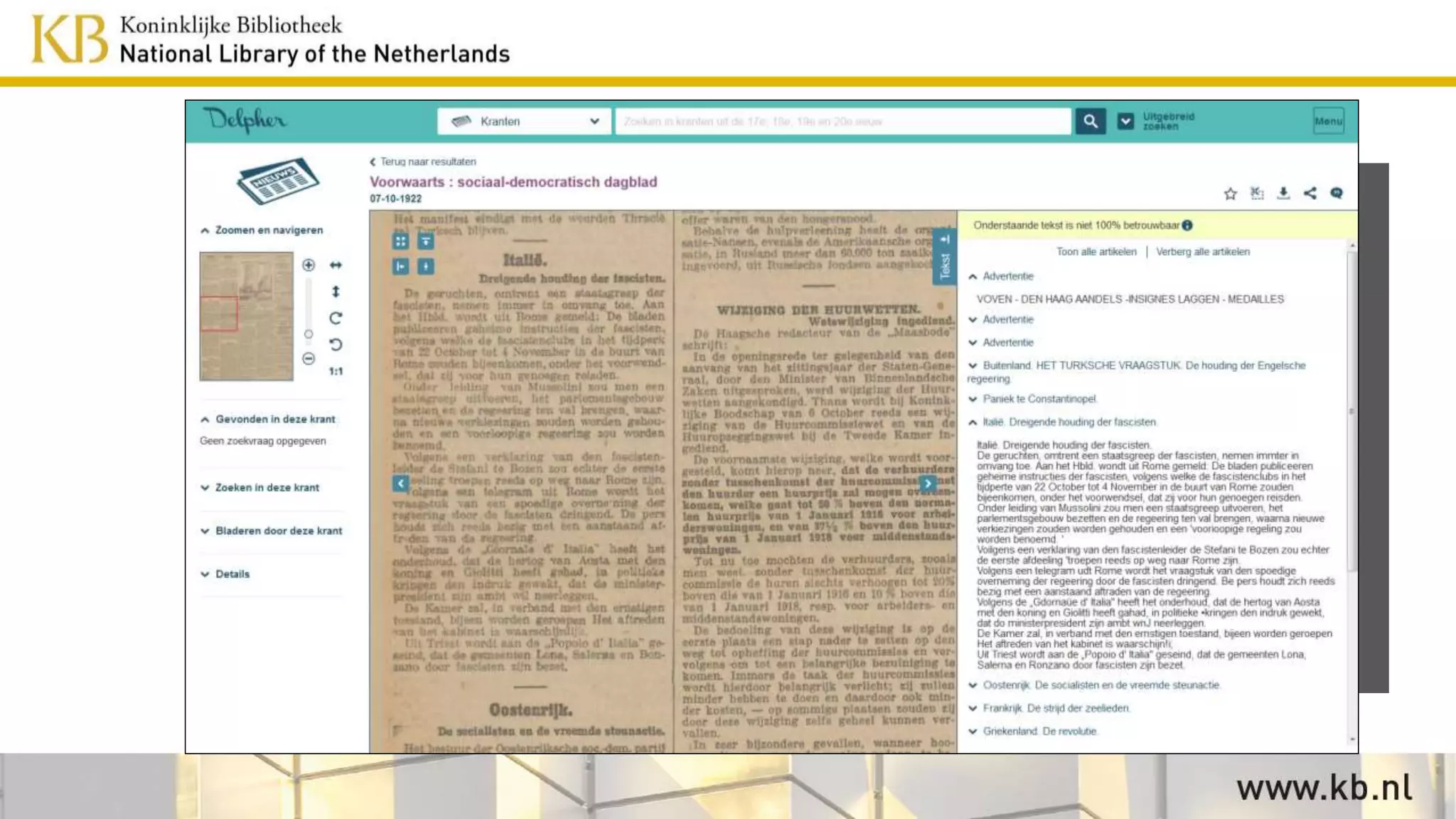

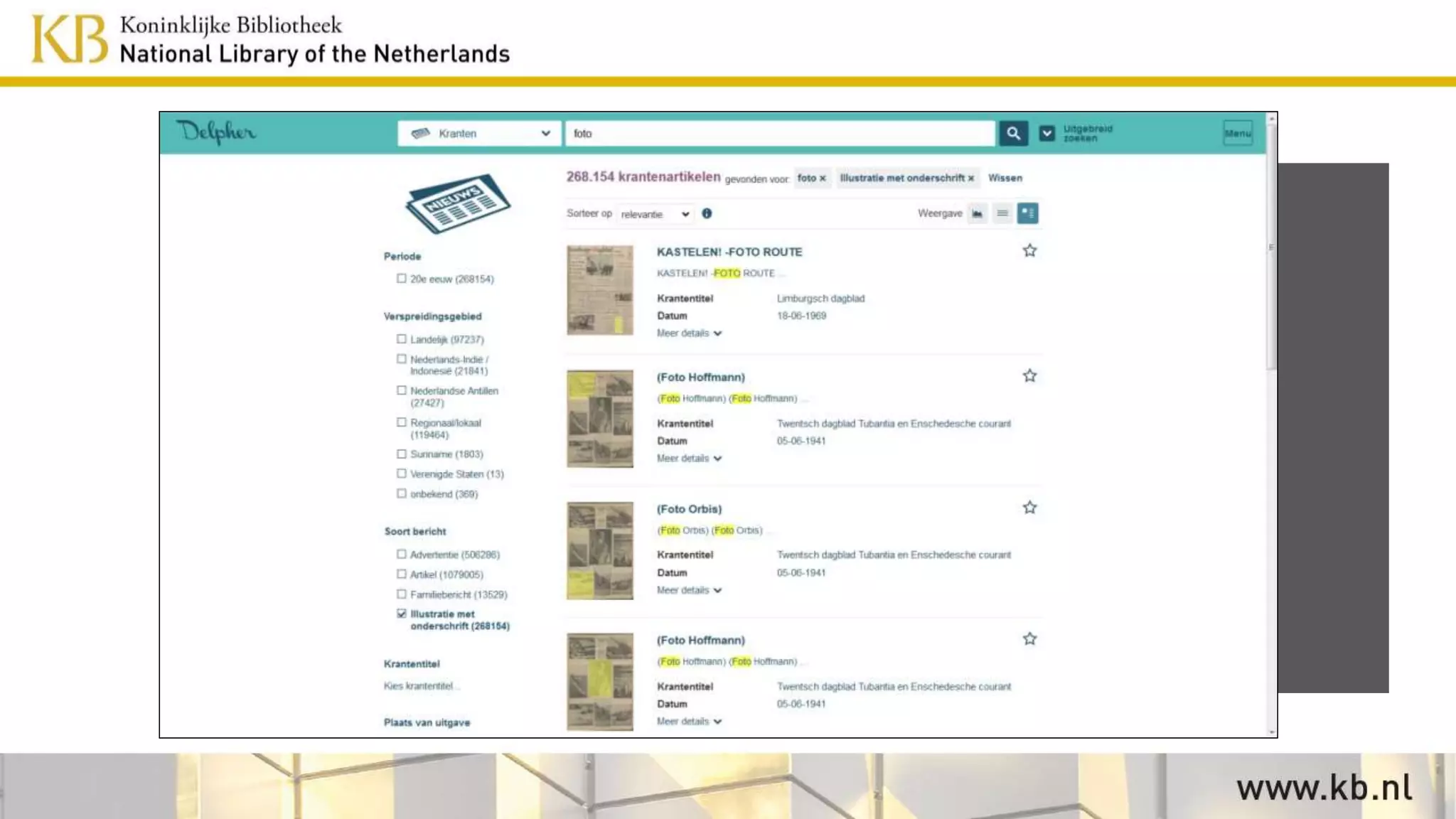

The document discusses the reuse of digital heritage at the KB library, highlighting its extensive collection and mission to make information accessible and usable. It emphasizes the importance of understanding user engagement, maintaining transparency in digitization processes, and collaborating with the community to enhance service delivery. The author encourages networking for sharing knowledge and promoting the library's resources.