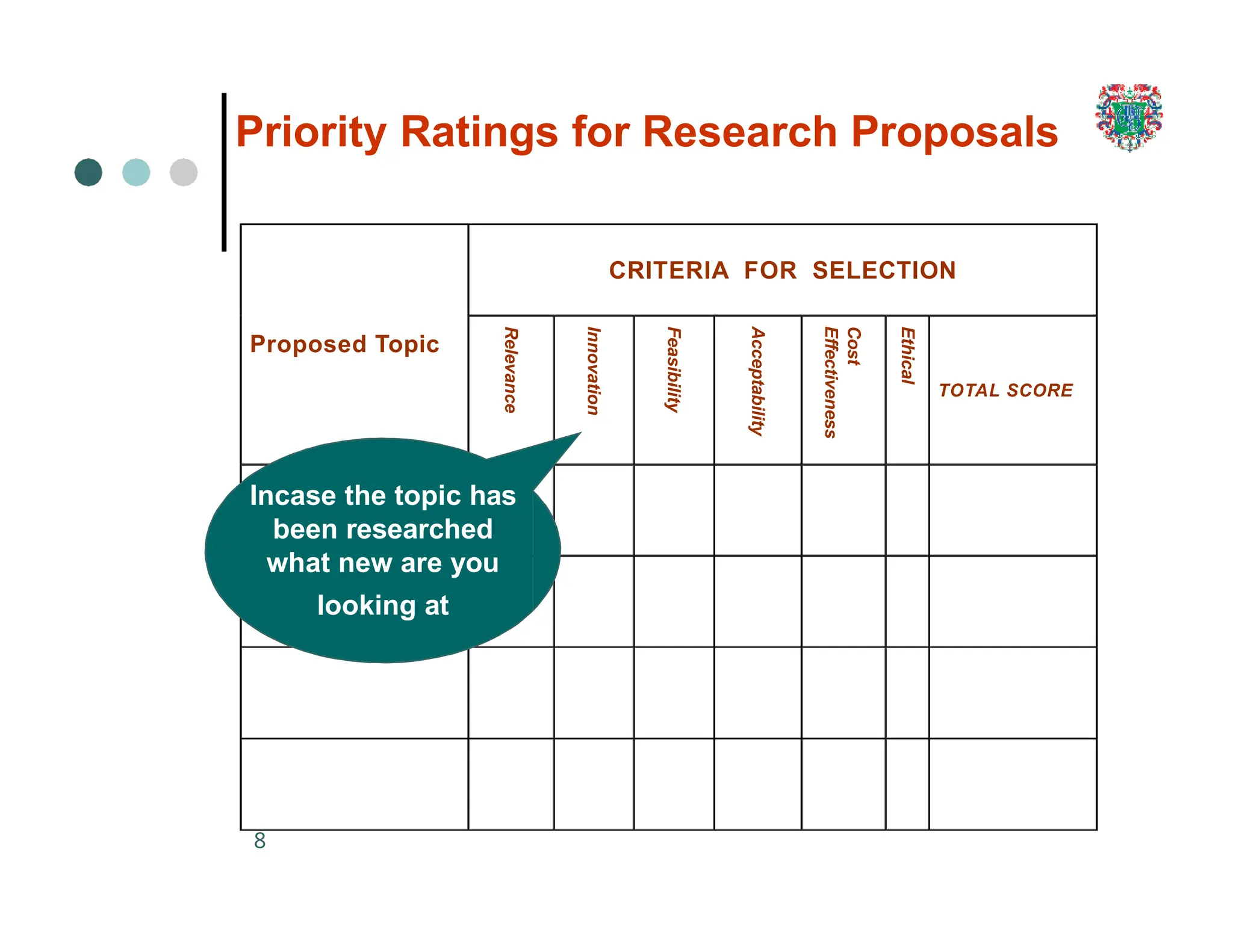

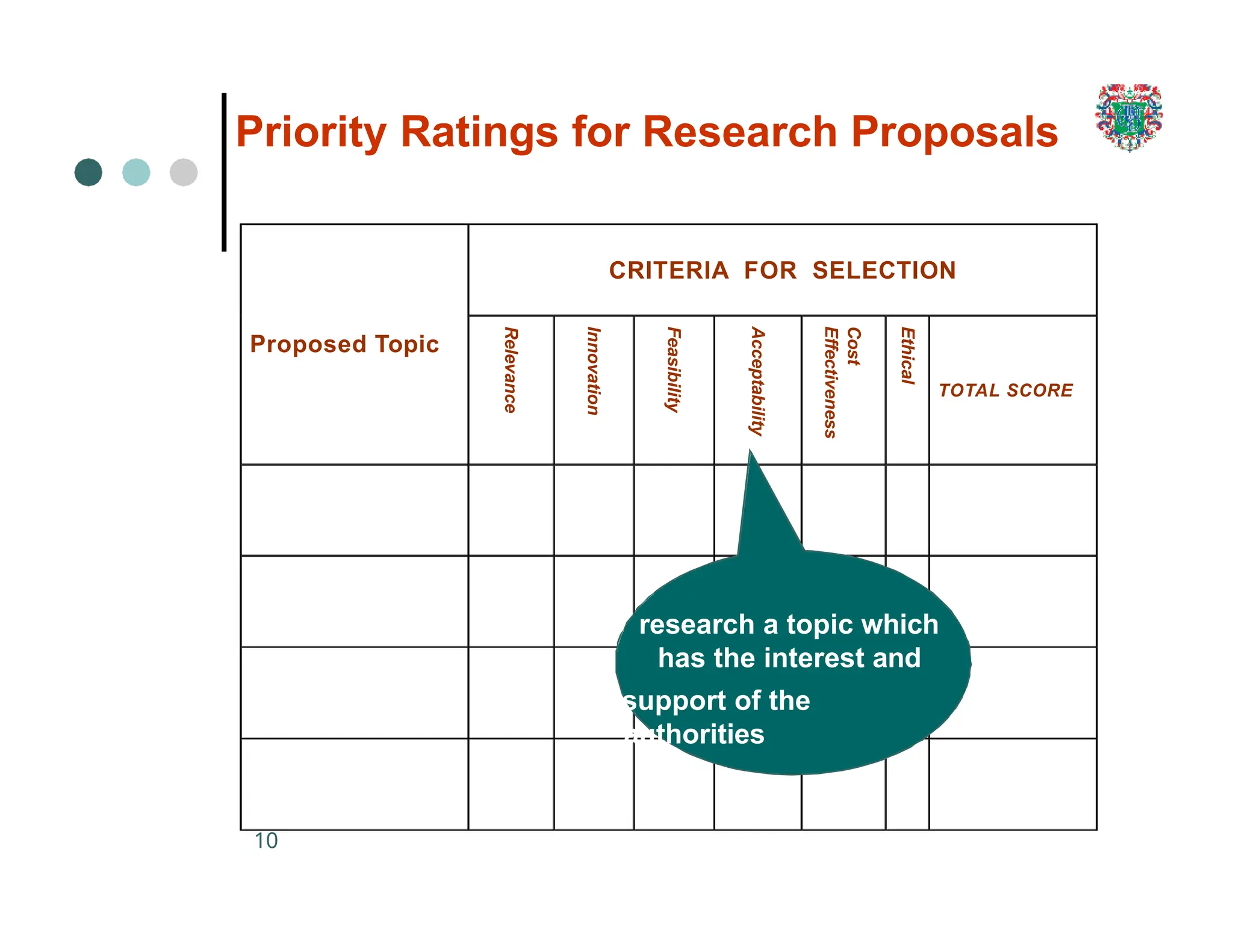

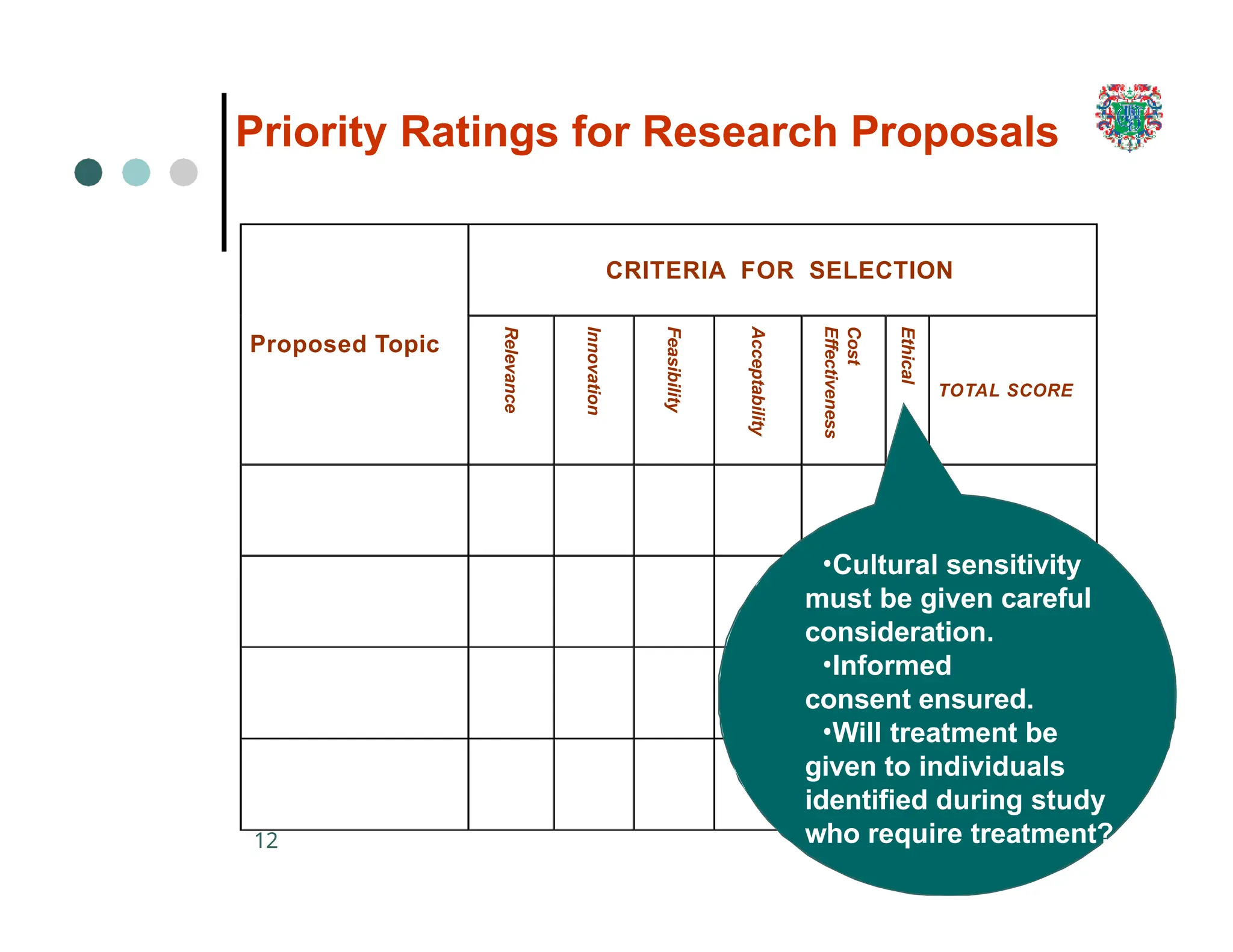

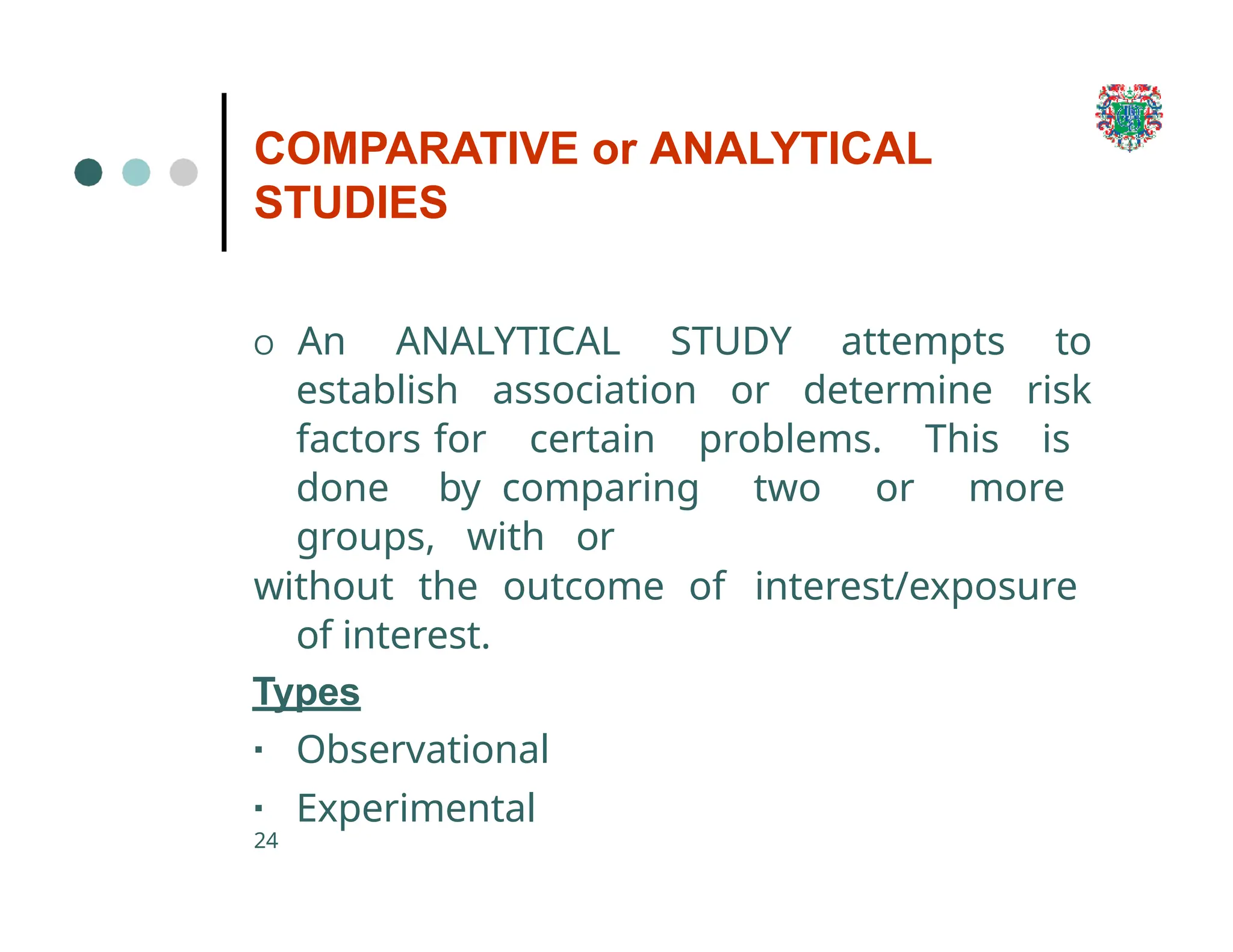

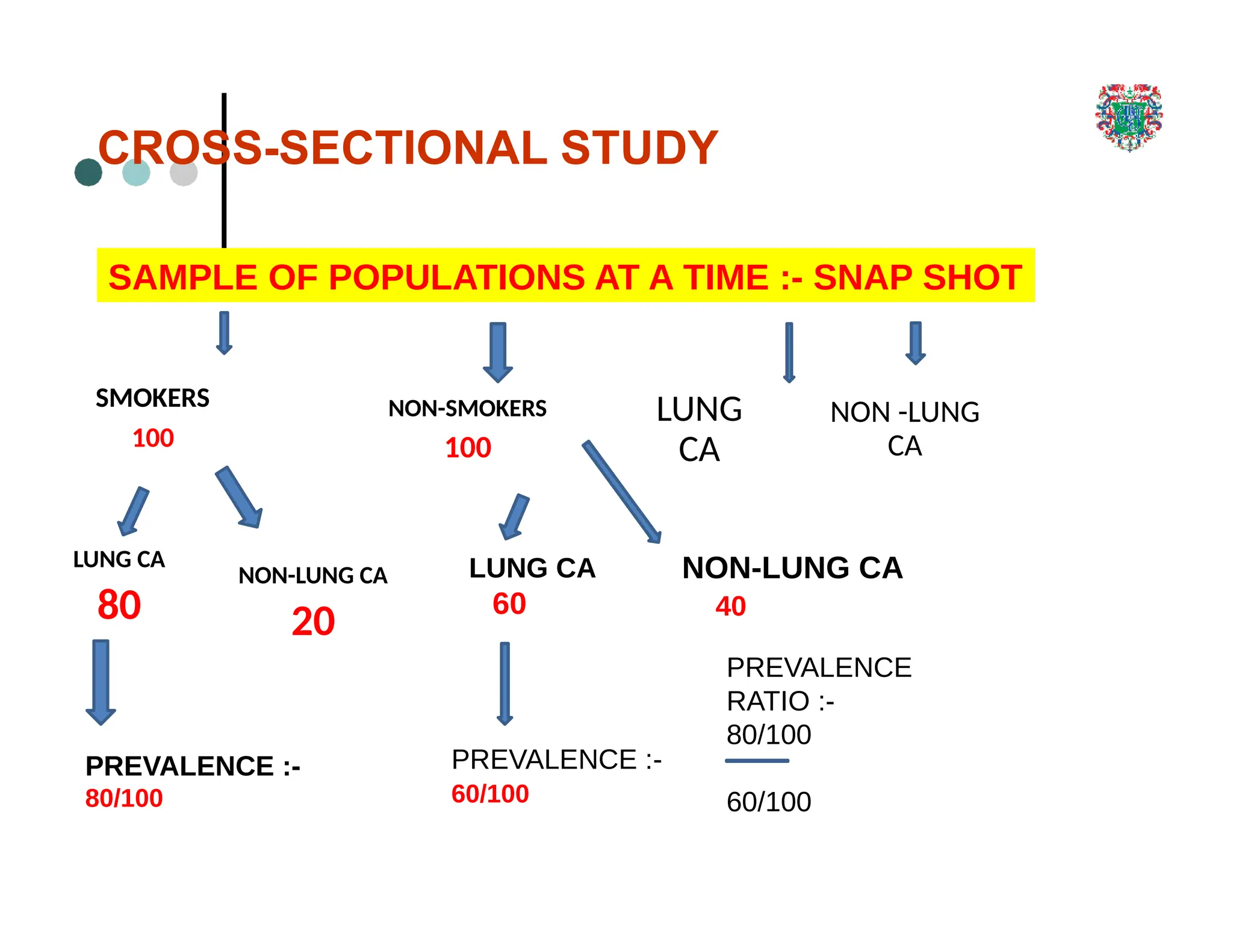

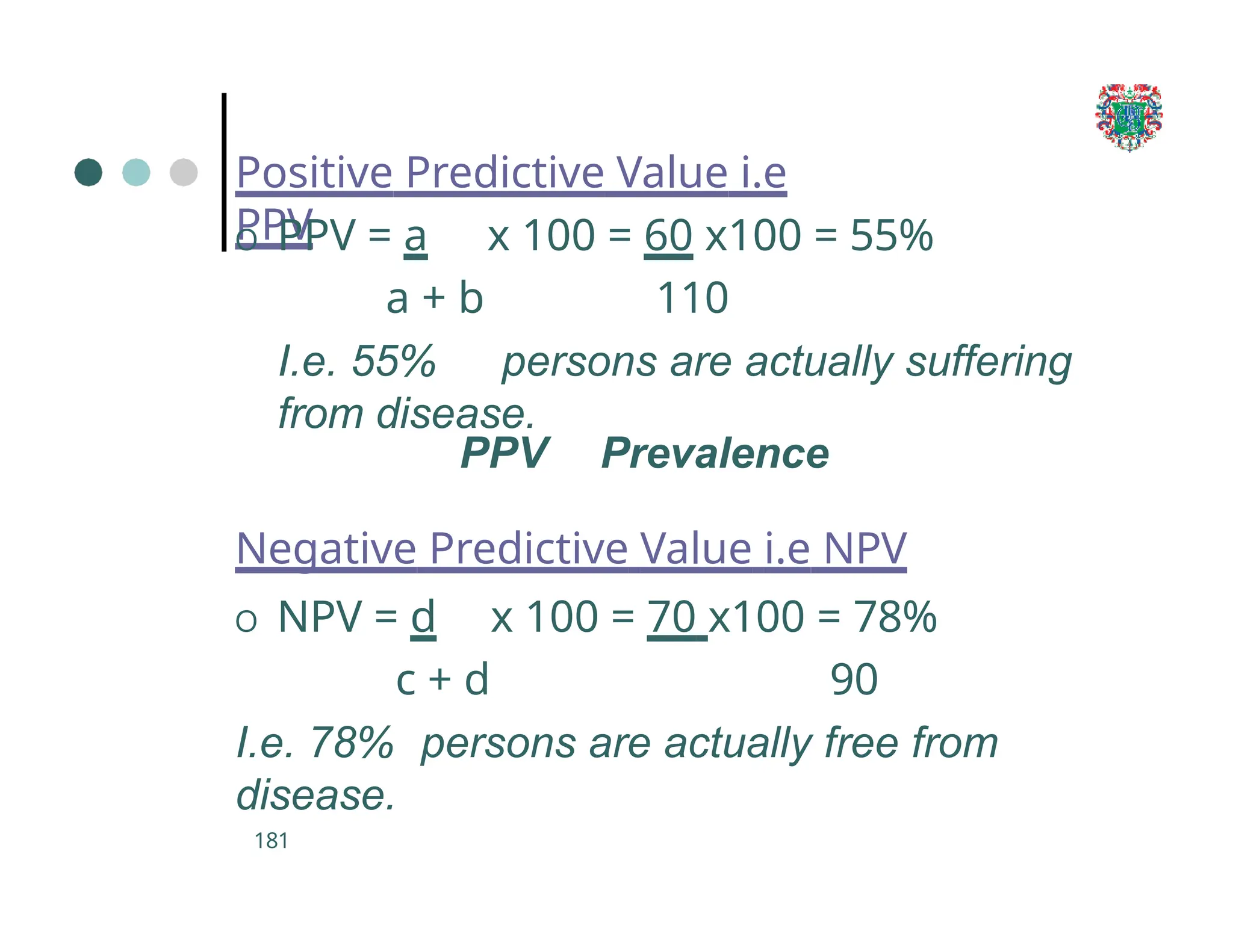

The document outlines the research process, including types of research (qualitative and quantitative) and the steps involved in designing and conducting research. It discusses criteria for selecting research topics, prioritization of research proposals, and various study designs, emphasizing the importance of operational definitions and sample selection. Additionally, it highlights different sampling methods and their advantages and disadvantages, along with the significance of differentiating between dependent and independent variables in health research.

![POINTS OF IMPORT IN DESIGNING A

QUESTIONNAIRE

188

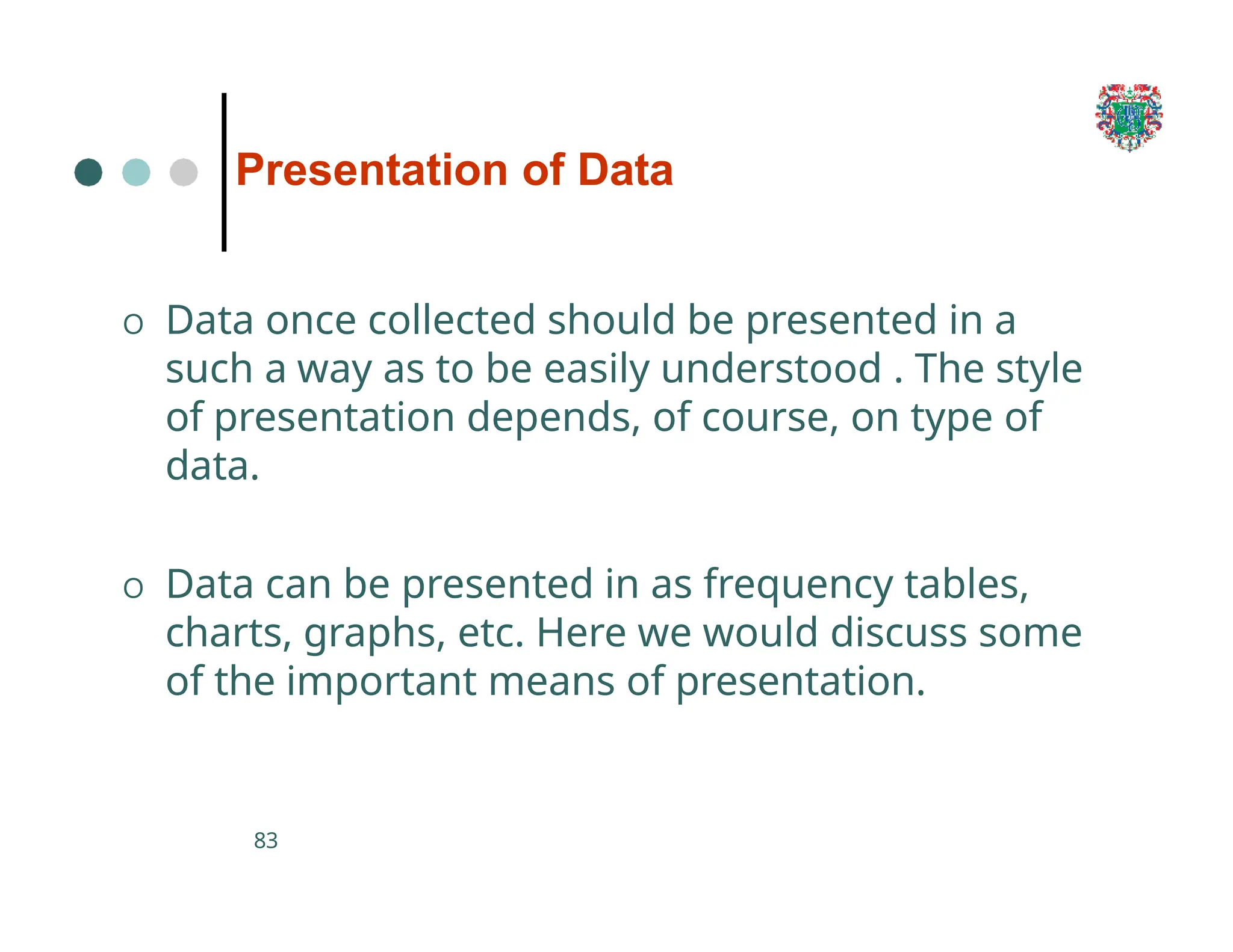

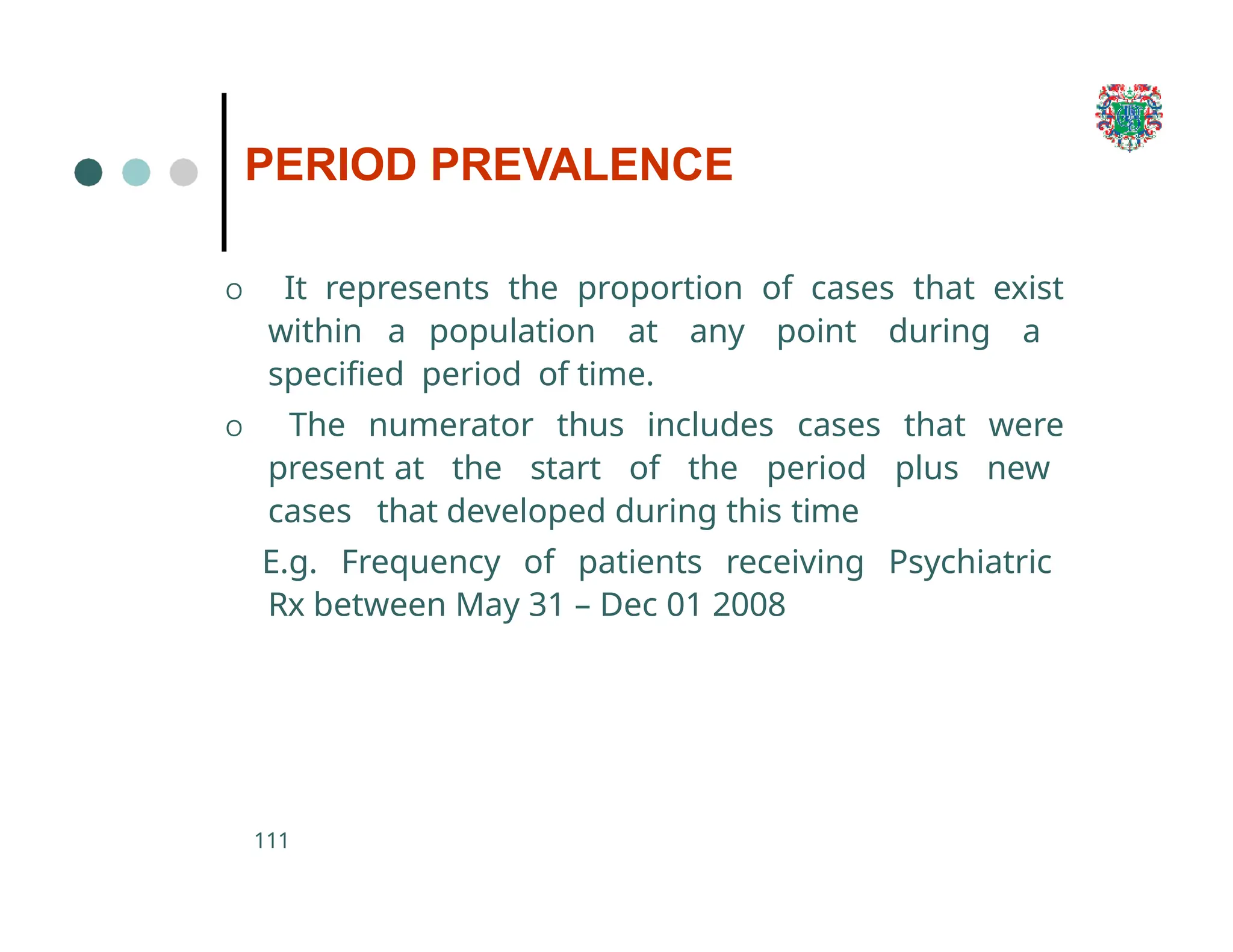

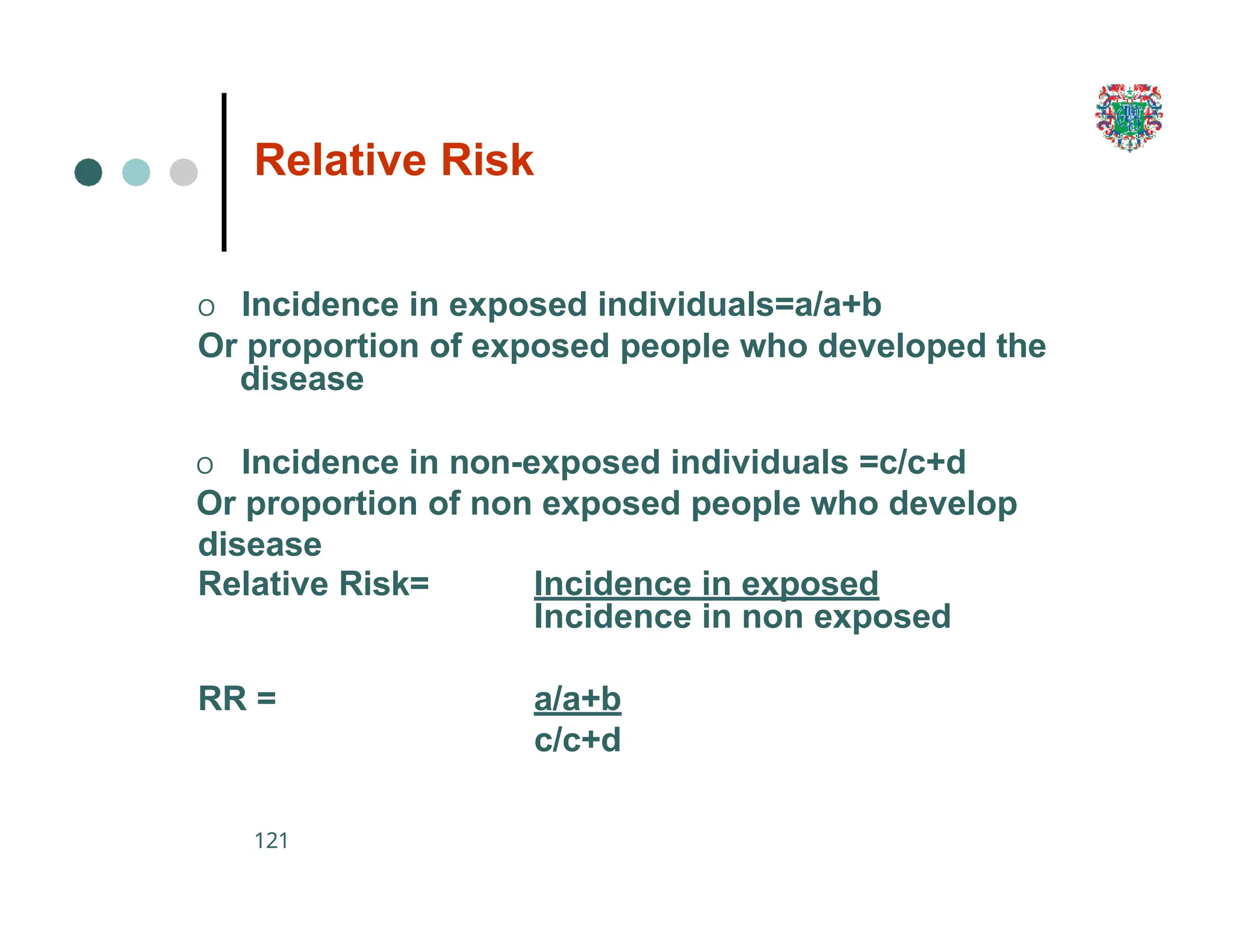

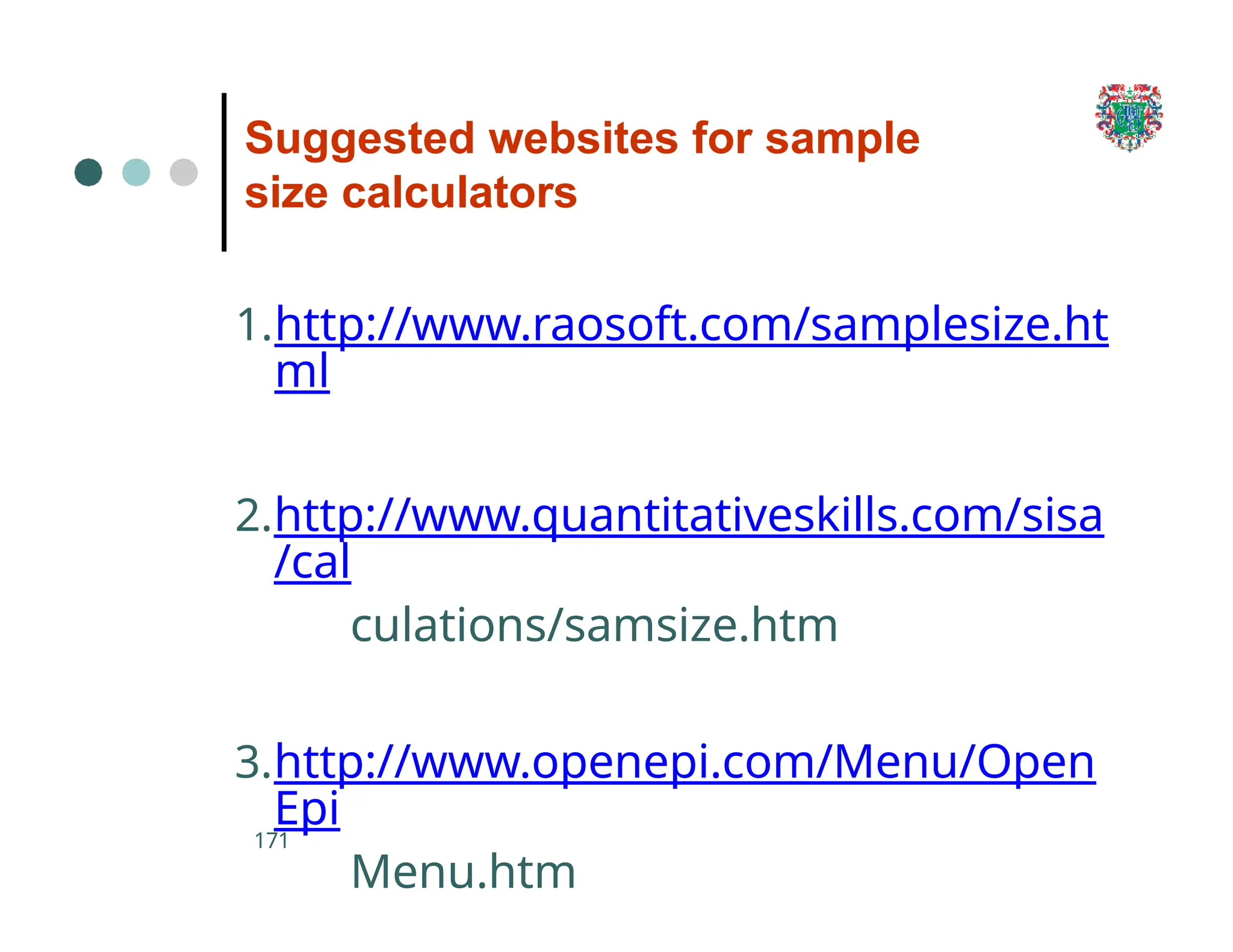

➢ Questions should be close ended, possible answers to close

ended questions should be lined vertically, preceded

by boxes, brackets or numbers

Example

How many different medicines do you take daily (check one)

[ ]

None [ ]

1-

2

[ ] 3-

4

[ ] 5-

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchpptnew-241123132755-92673709/75/research-PPT-NEW-pptx-henananannanannanann-188-2048.jpg)

![Dissertation Writing

Detailed discourse on a subject especially

submitted for a higher degree in a

University [Oxford]

213](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchpptnew-241123132755-92673709/75/research-PPT-NEW-pptx-henananannanannanann-205-2048.jpg)

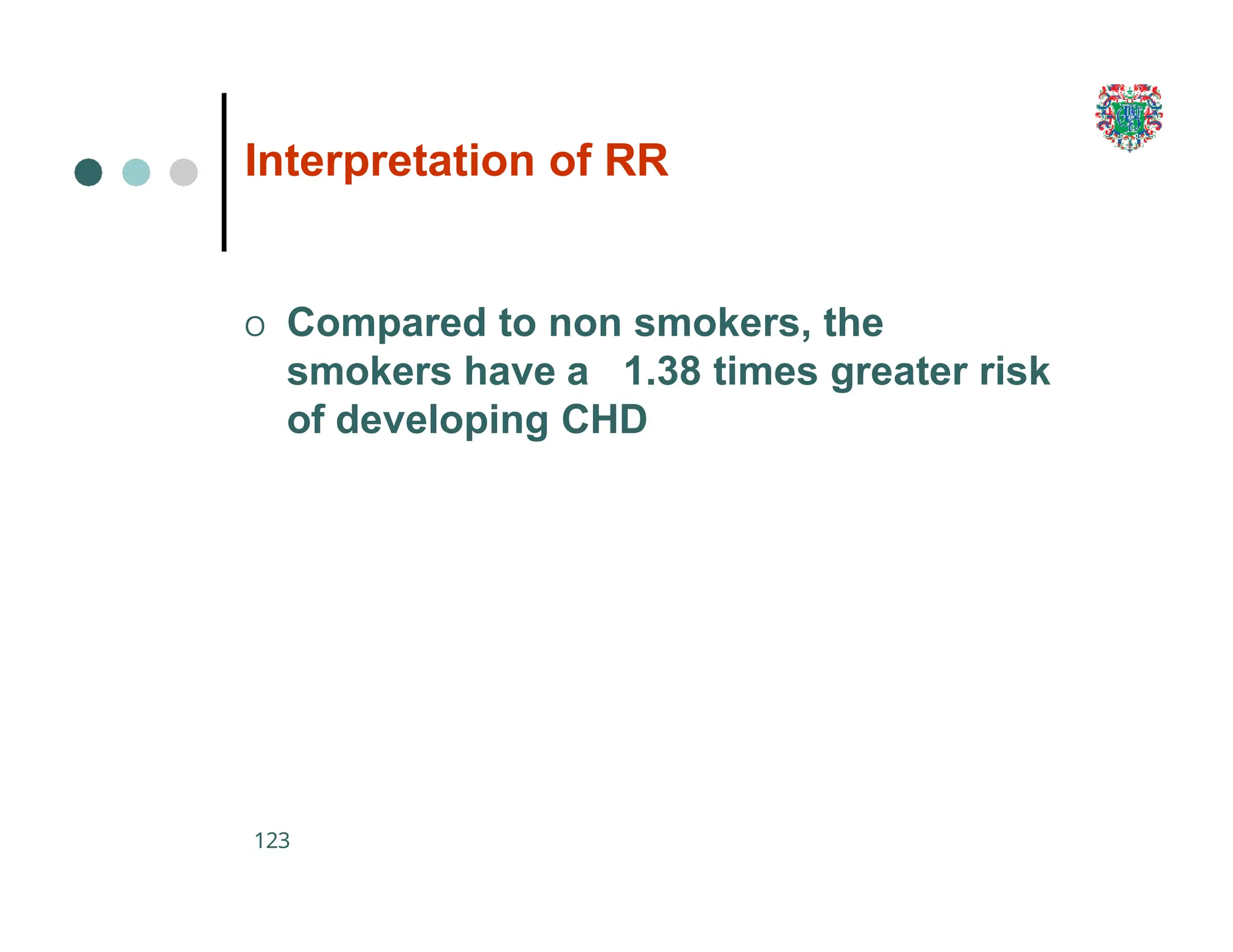

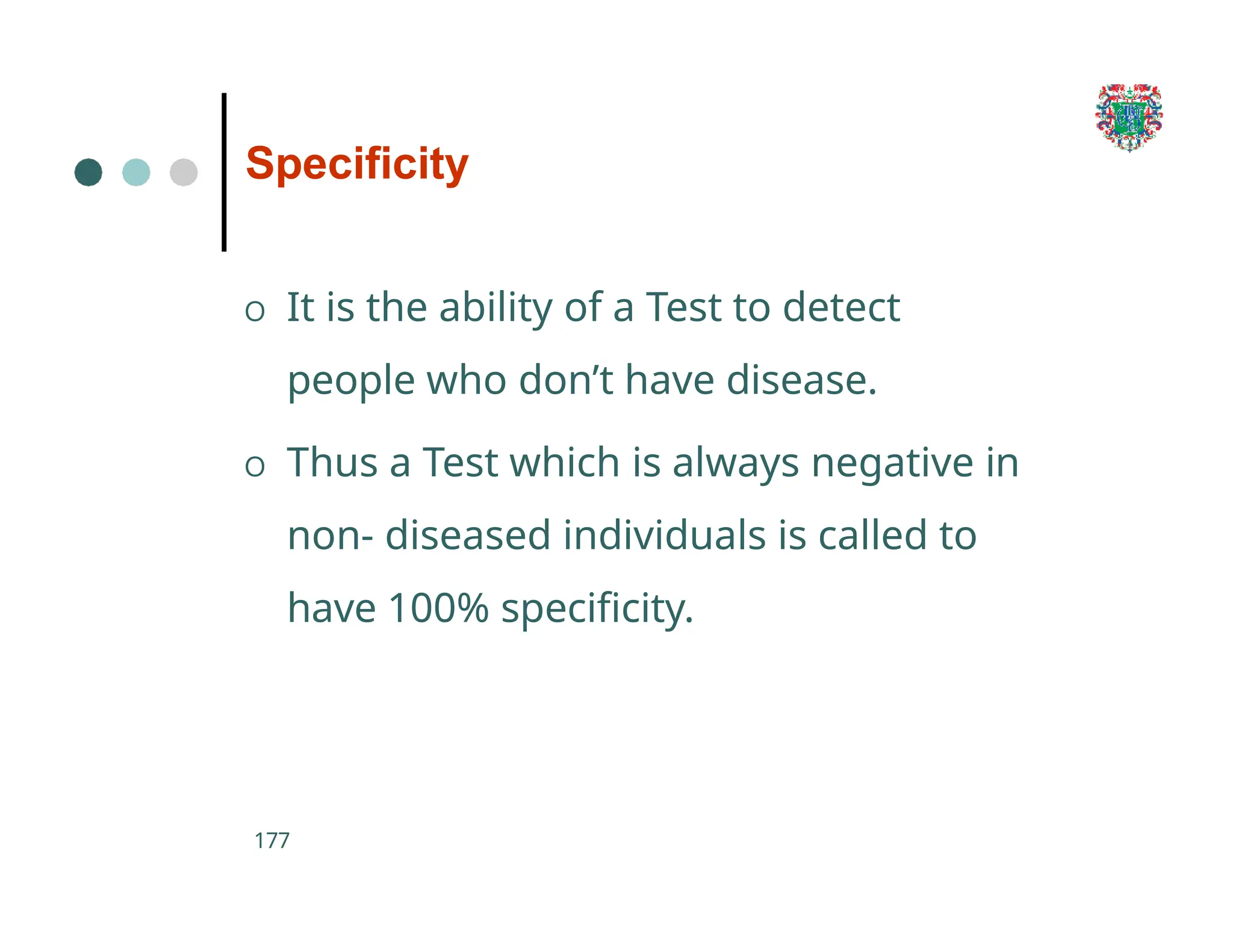

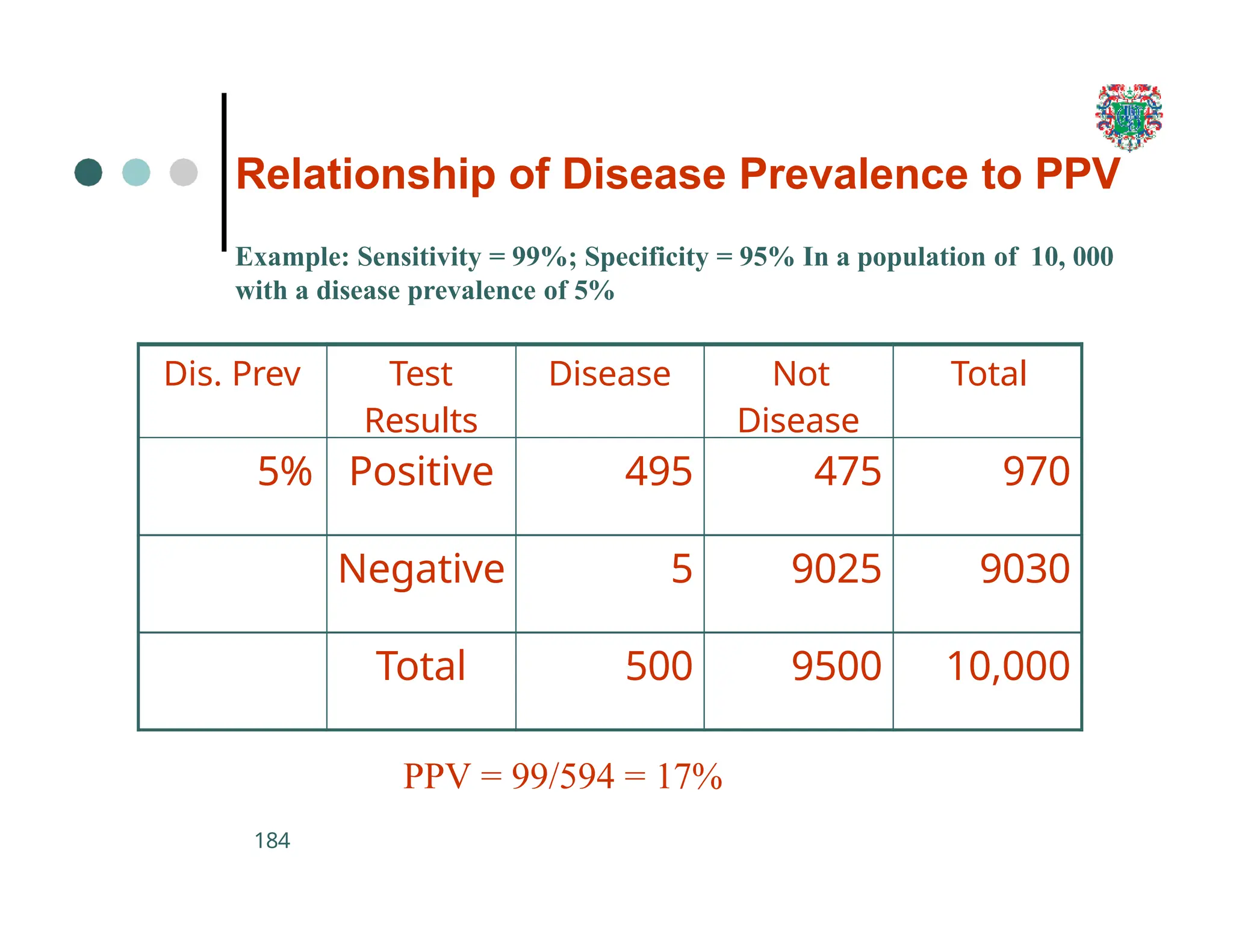

![Dissertation

240

O Borkowski MM. Infant sleep and

feeding: a telephone survey of Hispanic

Americans [dissertation]. Mount

Pleasant : Central Michigan University;

2002.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchpptnew-241123132755-92673709/75/research-PPT-NEW-pptx-henananannanannanann-240-2048.jpg)

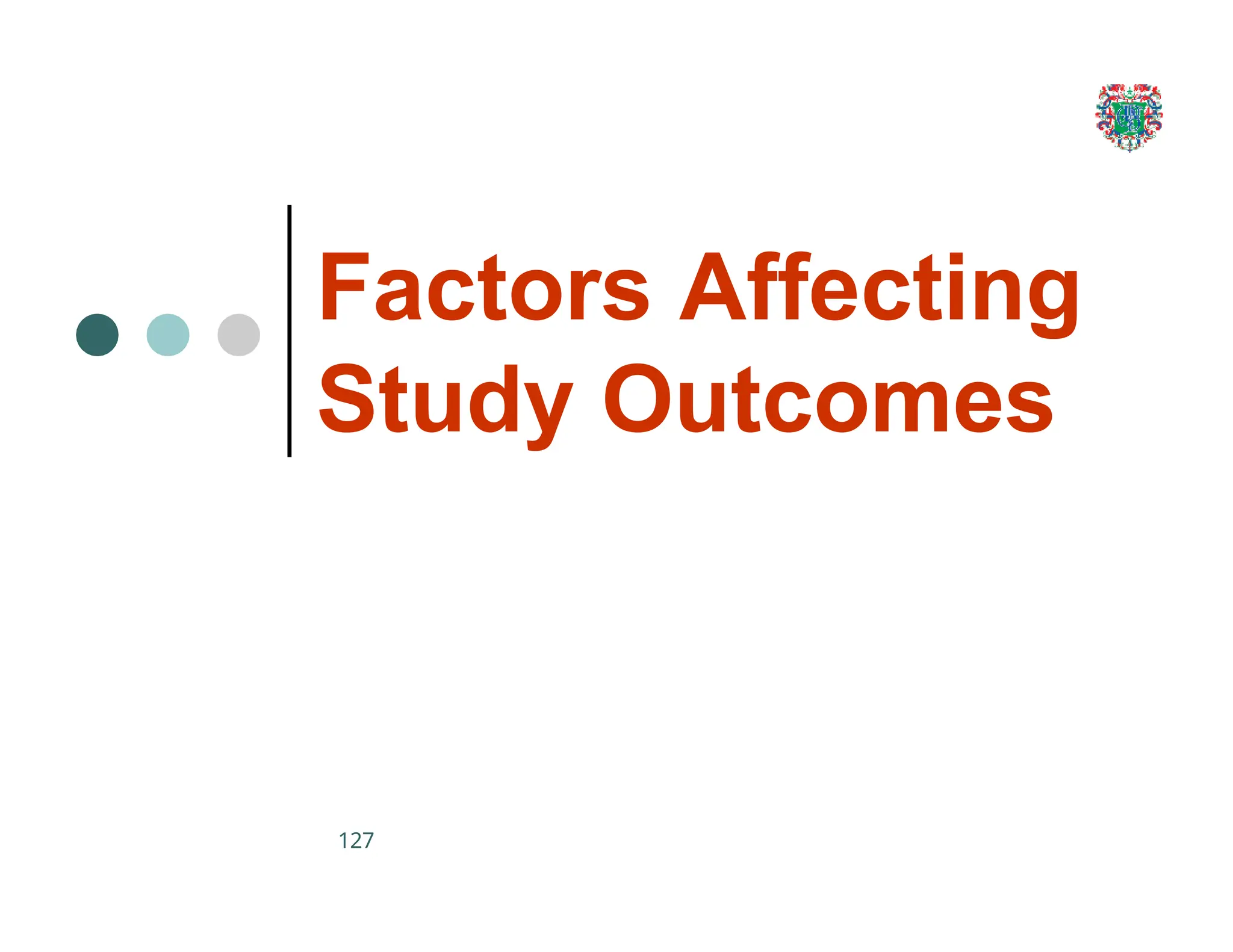

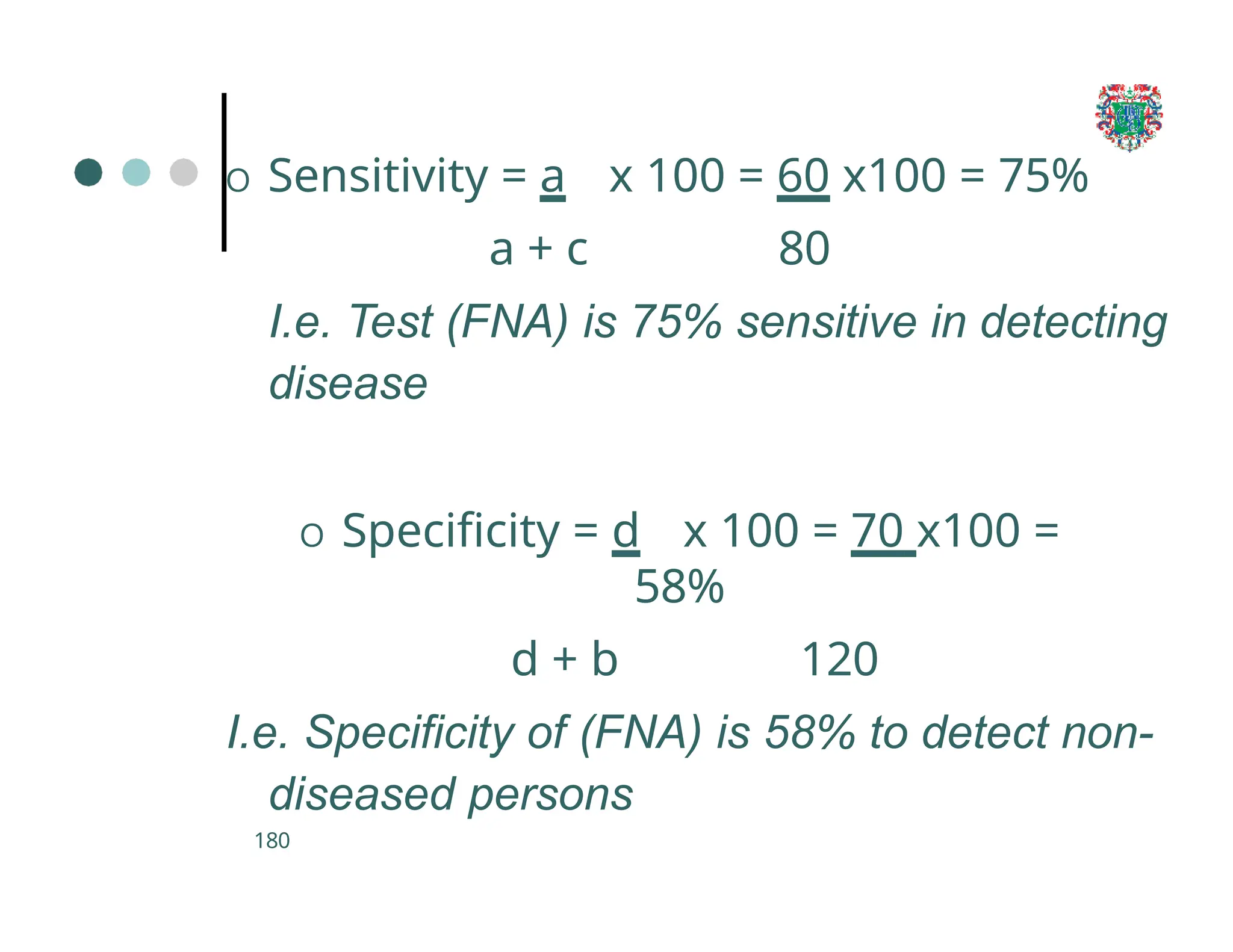

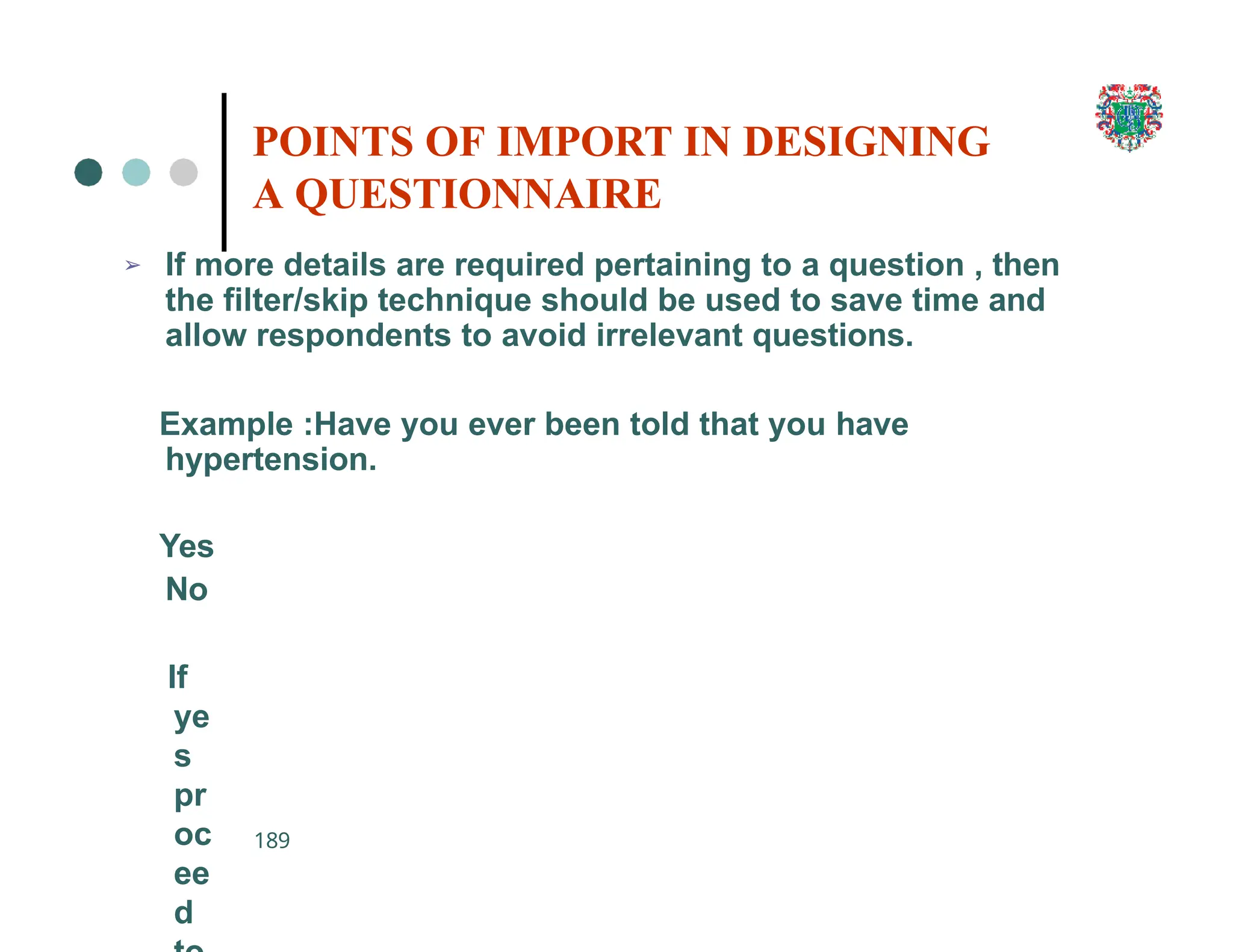

![Journal article on the Internet

241

O Abood S. Quality improvement initiative

in nursing homes: the ANA acts in an

advisory role. Am J Nurs [serial on the

Internet].

2002 Jun [cited 2002 Aug 12];102(6):[about

3 p.]. Available from:

http://www.nursingworld.org/AJN/2002/j

une/

Wawatch.htm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchpptnew-241123132755-92673709/75/research-PPT-NEW-pptx-henananannanannanann-241-2048.jpg)