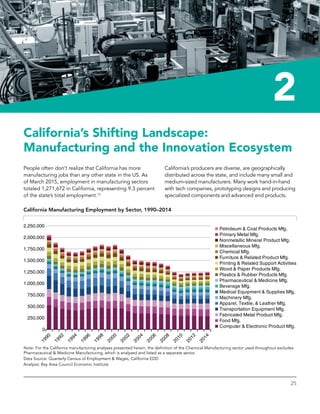

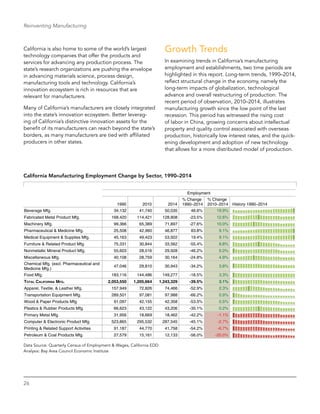

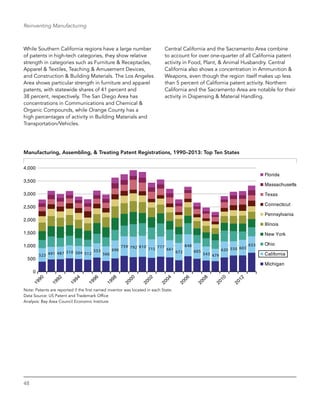

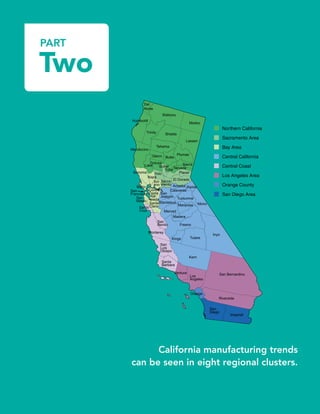

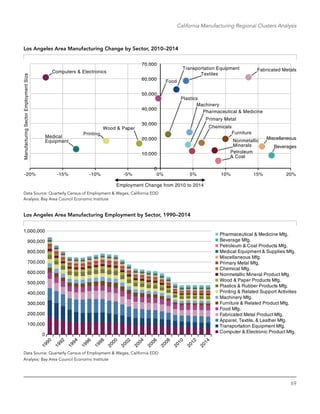

California is well-positioned to capture growth in manufacturing due to its large existing manufacturing base and strong innovation ecosystem. While manufacturing employment has declined since 1990 due to offshoring and automation, technological advances are now creating new opportunities. Shifting consumer expectations, globalization trends, and workforce needs are transforming the industry. California can strengthen its manufacturing environment by better linking research and business, growing skills training, increasing access to capital, and addressing high business costs.