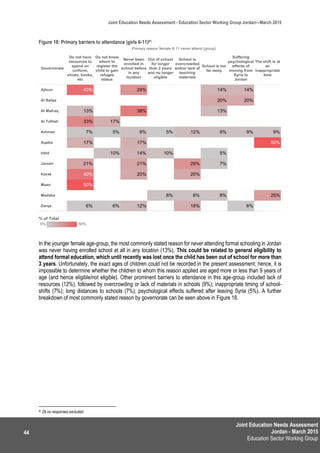

More than half of surveyed Syrian refugee households in Jordan had members under 18 years old. Around 61.6% of school-aged Syrian refugee children were attending formal education in Jordan, with attendance rates highest for younger children aged 6-11. Barriers to attendance included lack of resources to pay for schooling, needing to work, and lack of documentation. Non-formal and informal education programs were positively viewed but faced challenges like safety issues and lack of transportation. Only 46% of children with disabilities attended formal school, with physical accessibility being a key barrier. The assessment recommends improving awareness of education options, increasing accessibility, and addressing safety concerns to boost Syrian refugee children's access to education in Jordan.