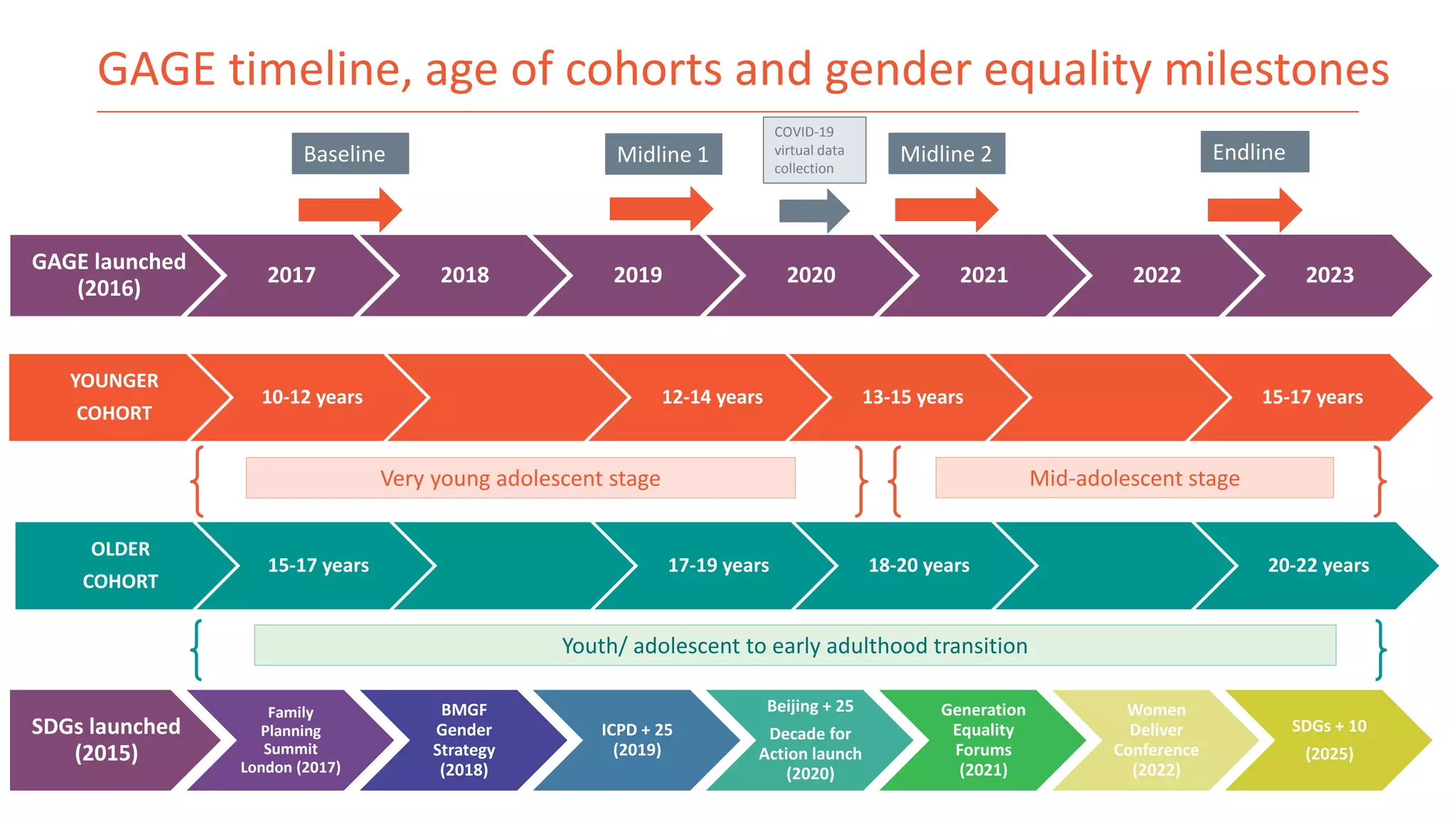

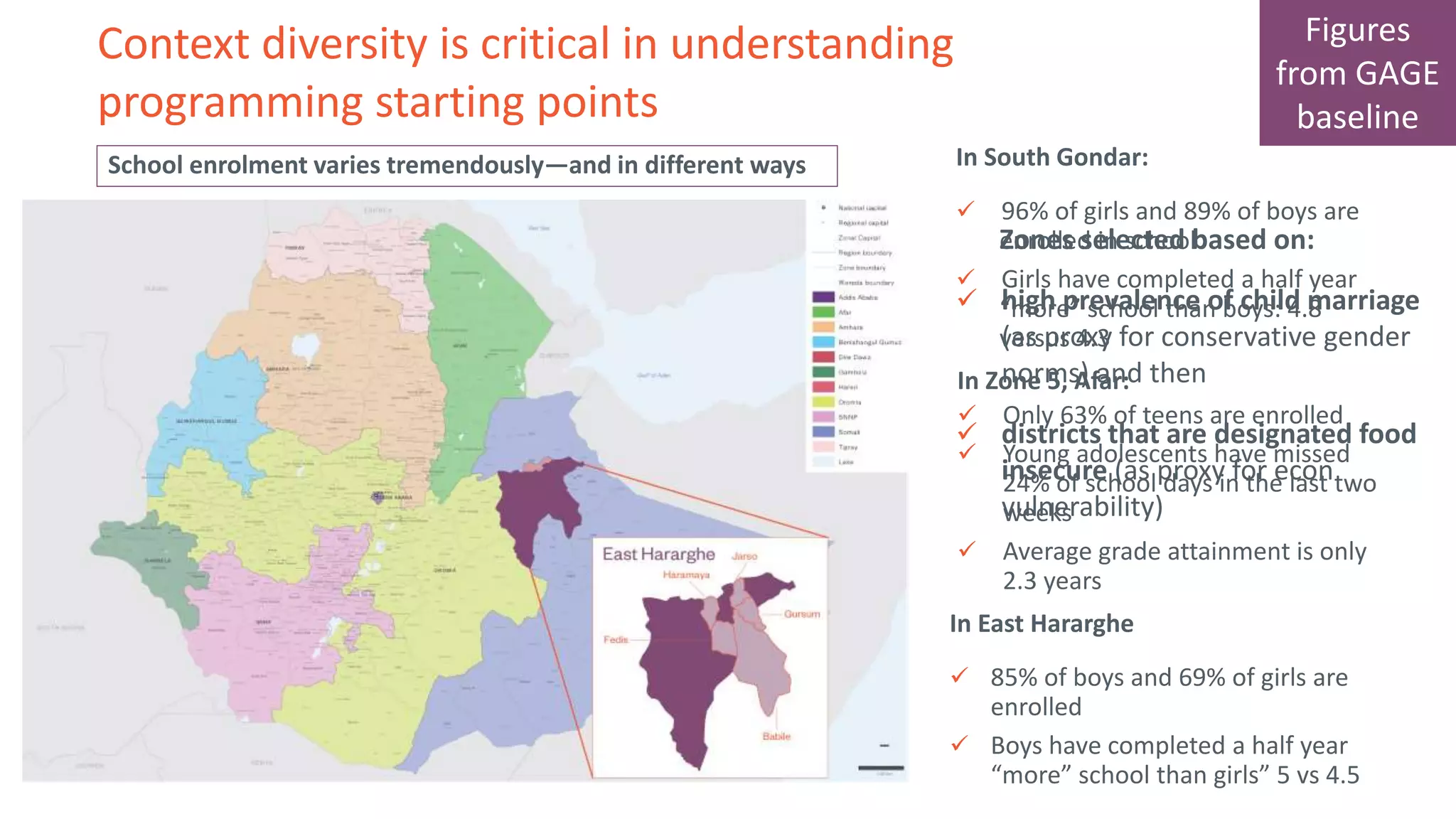

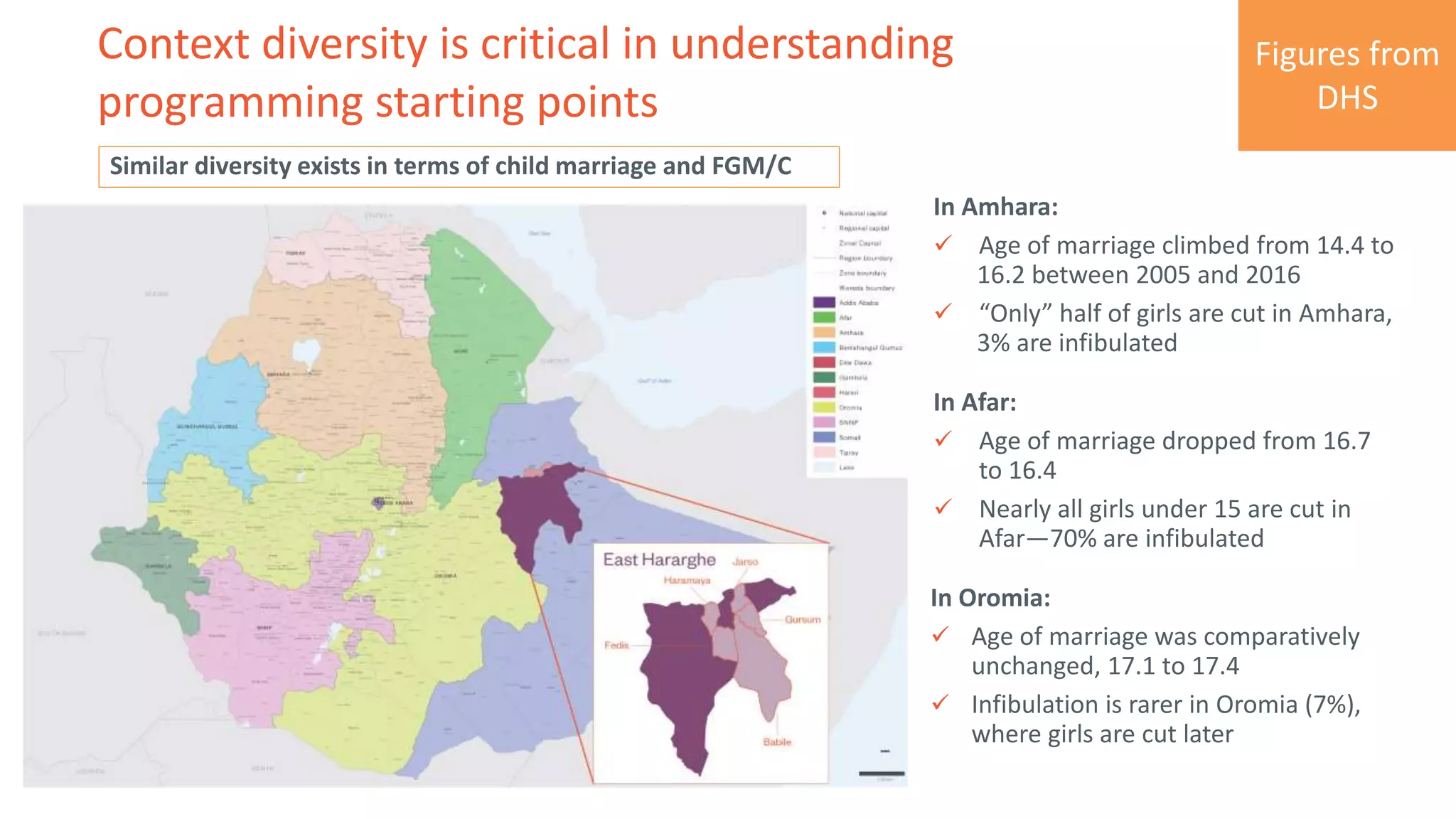

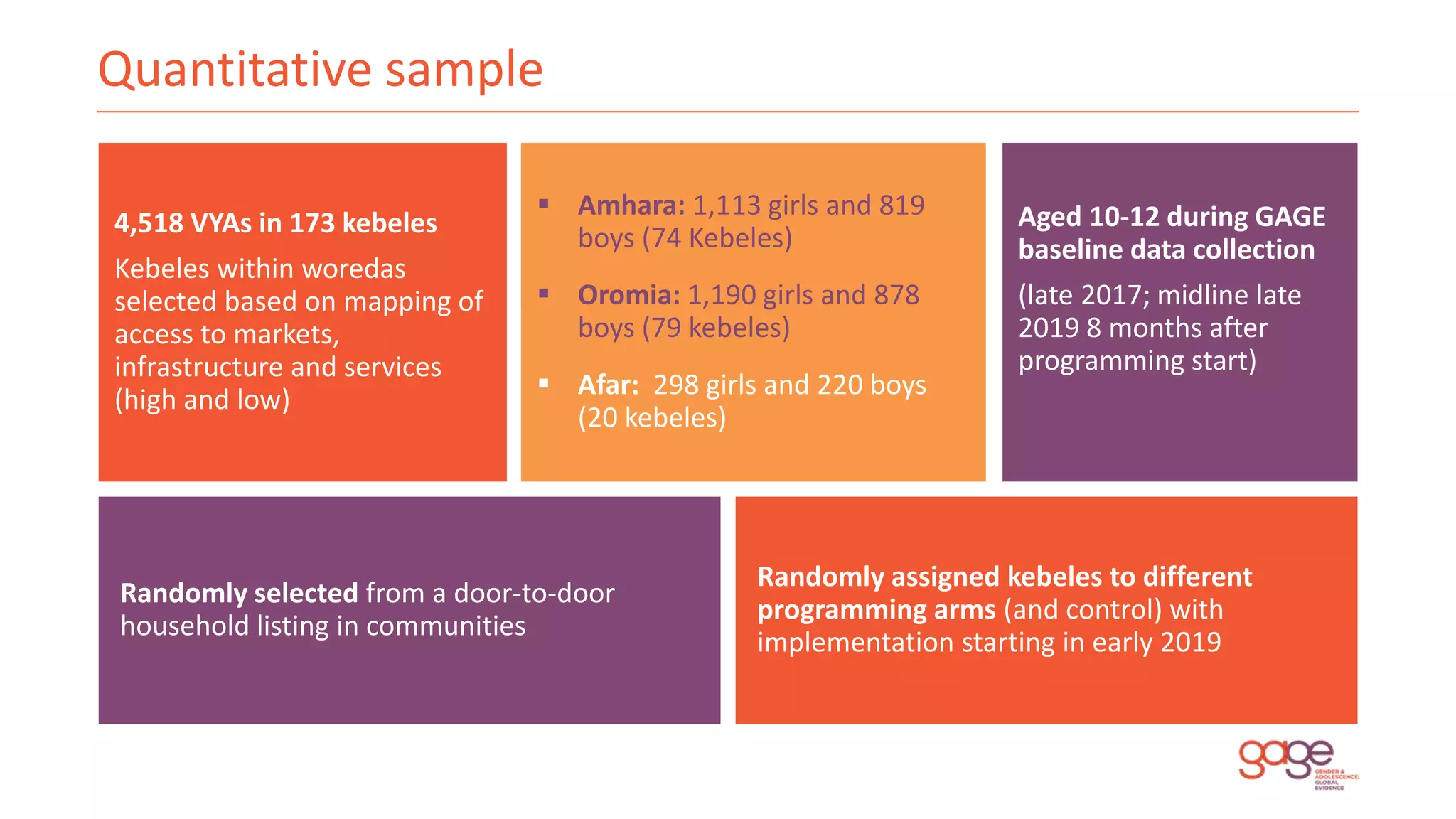

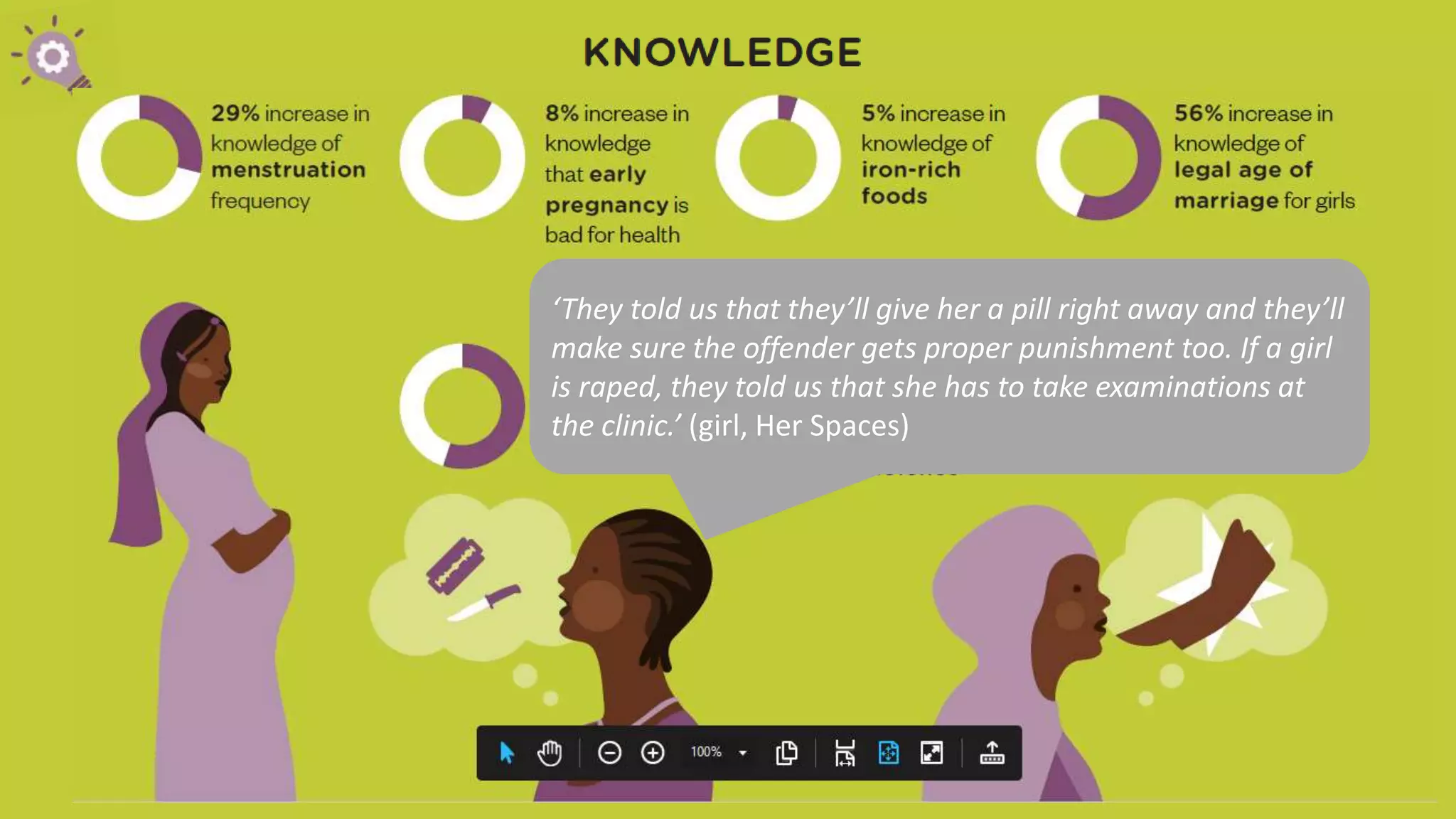

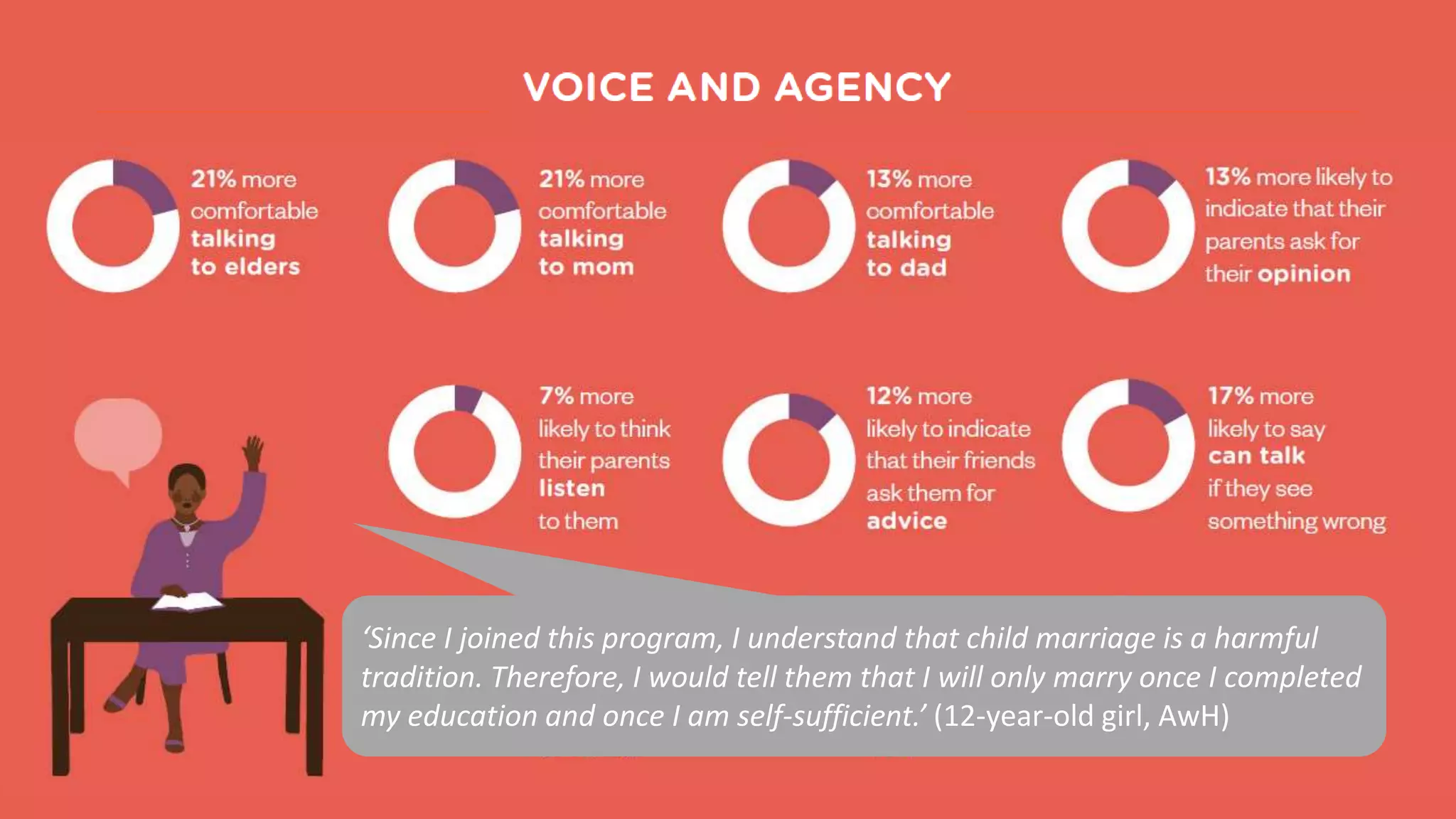

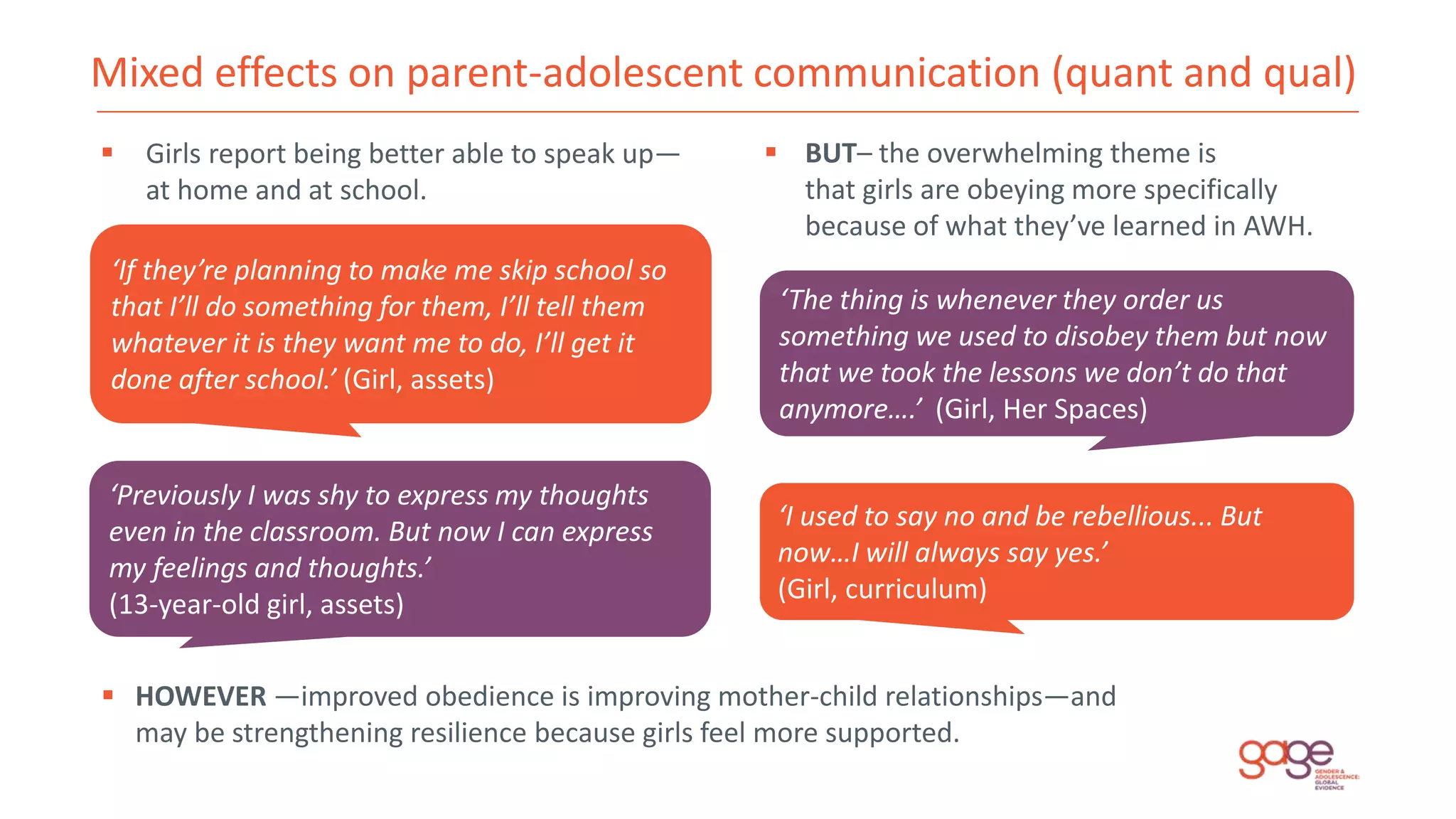

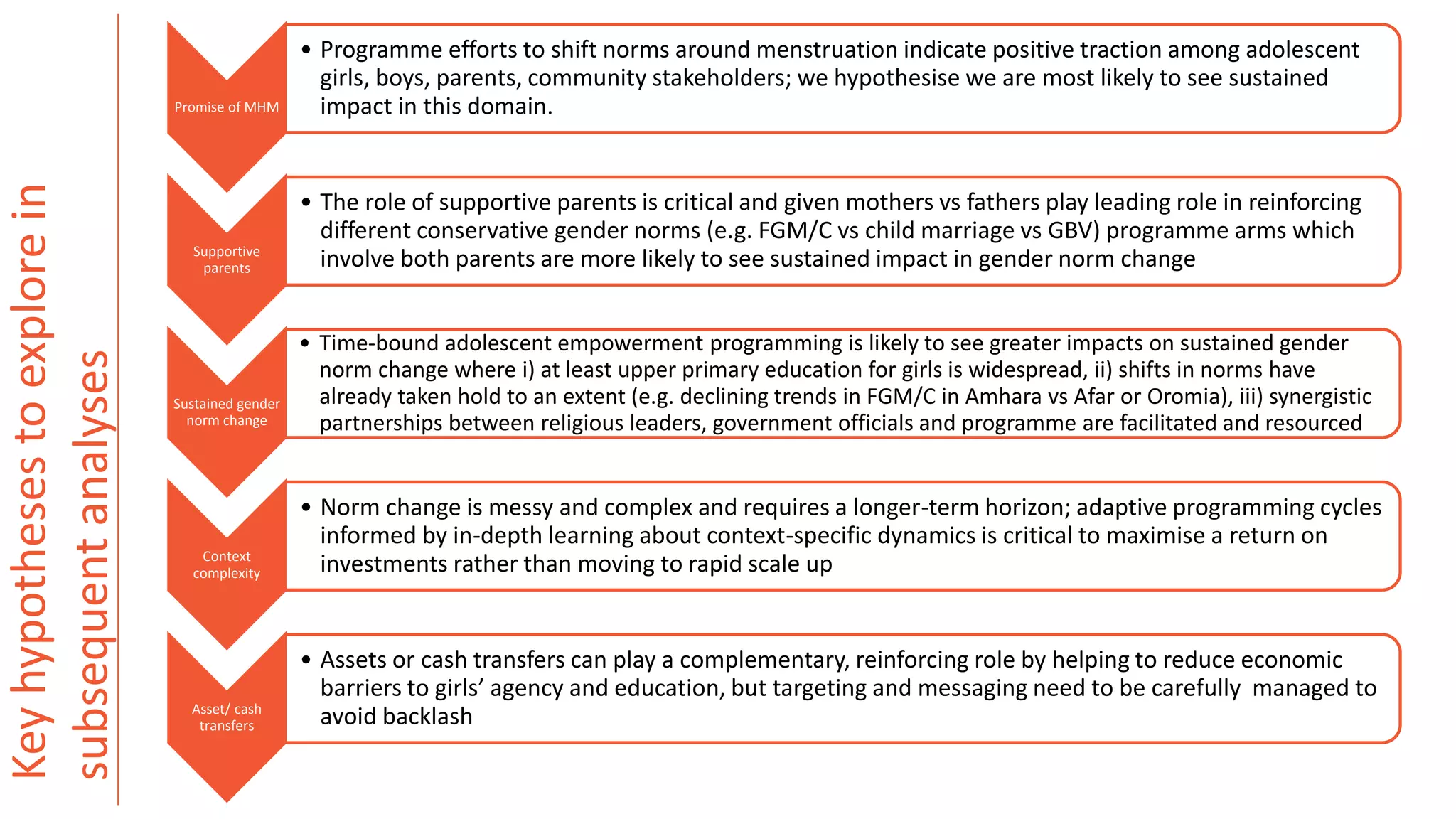

The document presents findings from the 'Act with Her' program aimed at improving the wellbeing of very young adolescents in Ethiopia, focusing on data from a mixed-methods impact evaluation. It highlights the need for further evidence on the effectiveness of community-based girls' clubs, indicating significant short-term positive outcomes related to mental health, resilience, and knowledge among participants. The evaluation also emphasizes the importance of understanding context diversity and the potential benefits of targeting additional demographics, such as boys and parents.

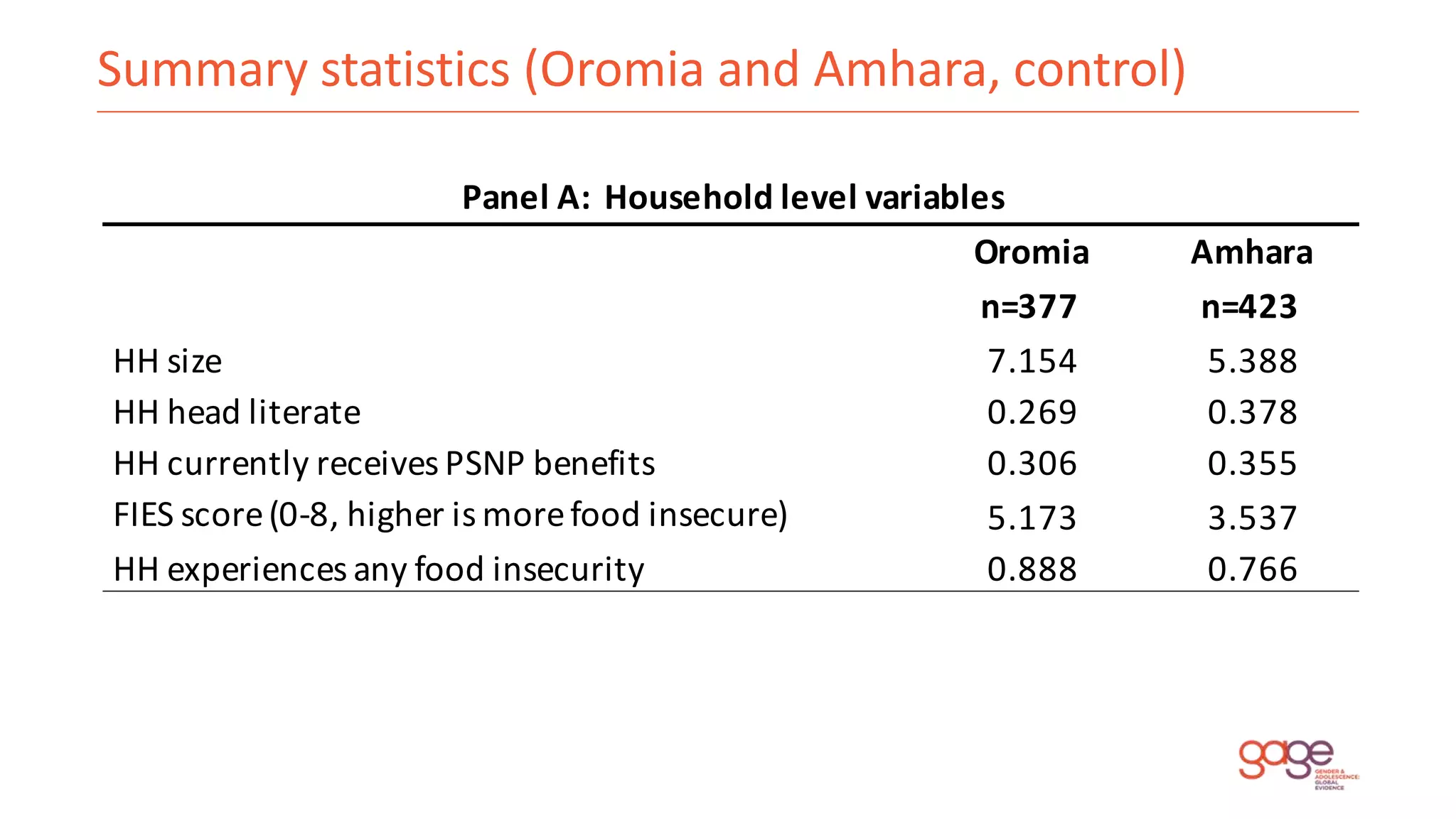

![Girls’ primary indices (subset)

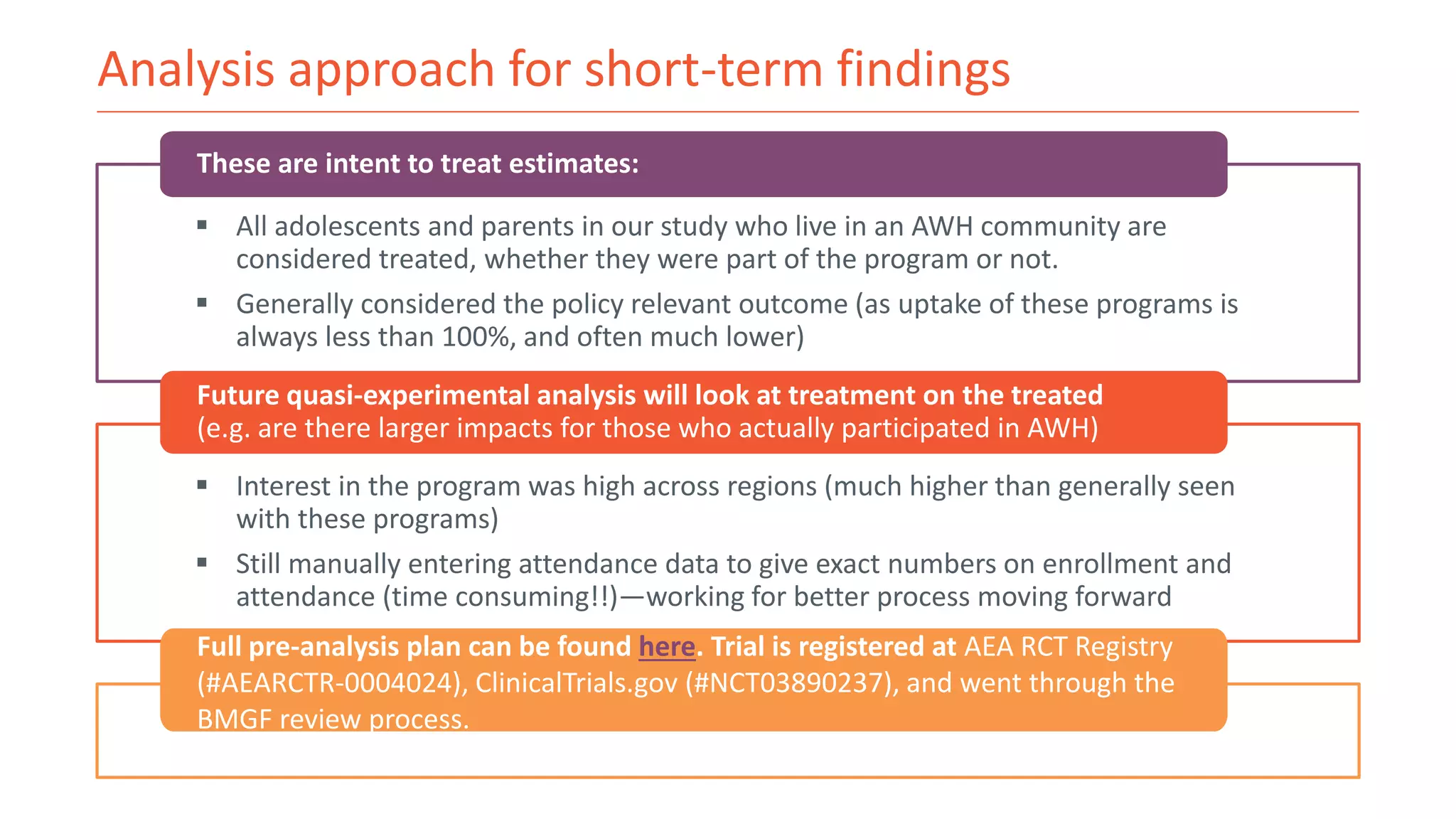

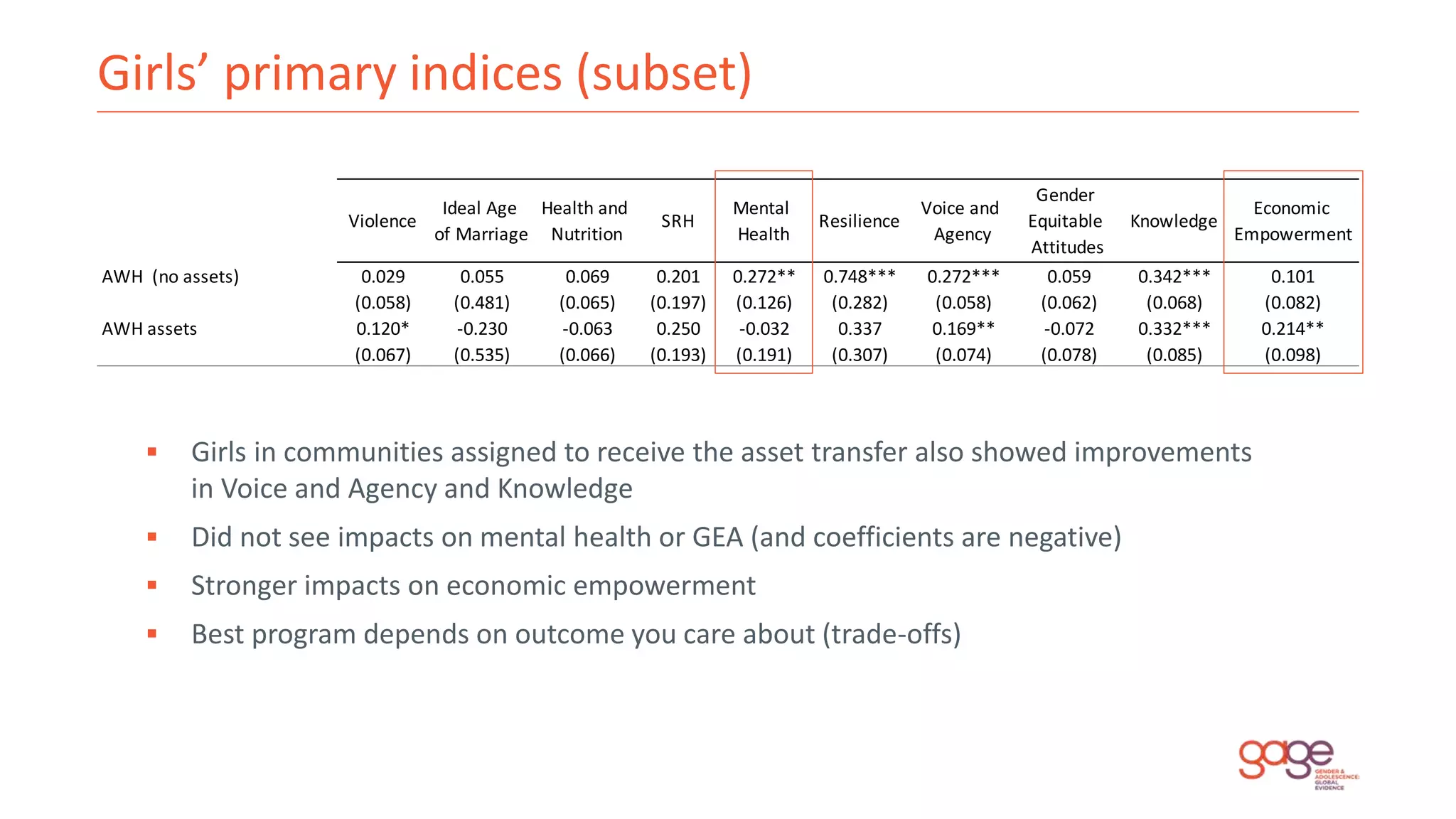

Indices ensure not ‘cherry picking’ outcomes of impact

Coefficients generally all in the right direction (positive is good), with larger coefficients for the AWH

arm, Limited significant difference between Her Spaces and AWH in the short term, except for mental

health and attitudes

SRH limited to those already menstruating (~10% of sample)

Significant impacts on mental health, resilience, voice and agency and knowledge provide

a pathway to longer-run impacts.

Violence

Ideal Age

of Marriage

Health and

Nutrition

SRH

Mental

Health

Resilience

Voice and

Agency

Gender

Equitable

Attitudes

Knowledge

Her Spaces 0.071 -0.029 0.090 0.044 0.057 0.735** 0.189*** -0.080 0.292***

(0.062) (0.504) (0.080) (0.249) (0.131) (0.320) (0.069) (0.067) (0.086)

AWH (no assets) 0.029 0.055 0.069 0.201 0.272** 0.748*** 0.272*** 0.059 0.342***

(0.058) (0.481) (0.065) (0.197) (0.126) (0.282) (0.058) (0.062) (0.068)

P-value: B1 /= B2 [0.475] [0.844] [0.790] [0.520] [0.027] [0.969] [0.149] [0.030] [0.510]

Control Mean 0.000 22.435 -0.000 0.000 26.412 31.310 0.000 0.000 0.000

Observations 1553 1534 1612 189 1520 1372 1488 1584 1536](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbcoo5mjq1weln6wszgk-signature-bc697695088383fffb0cd6e78d2b9aa46849f09cdce57c0d5f49793eec47d99a-poli-210603083853/75/Act-With-Her-Ethiopia-Short-run-findings-on-programming-with-Very-Young-Adolescents-22-2048.jpg)

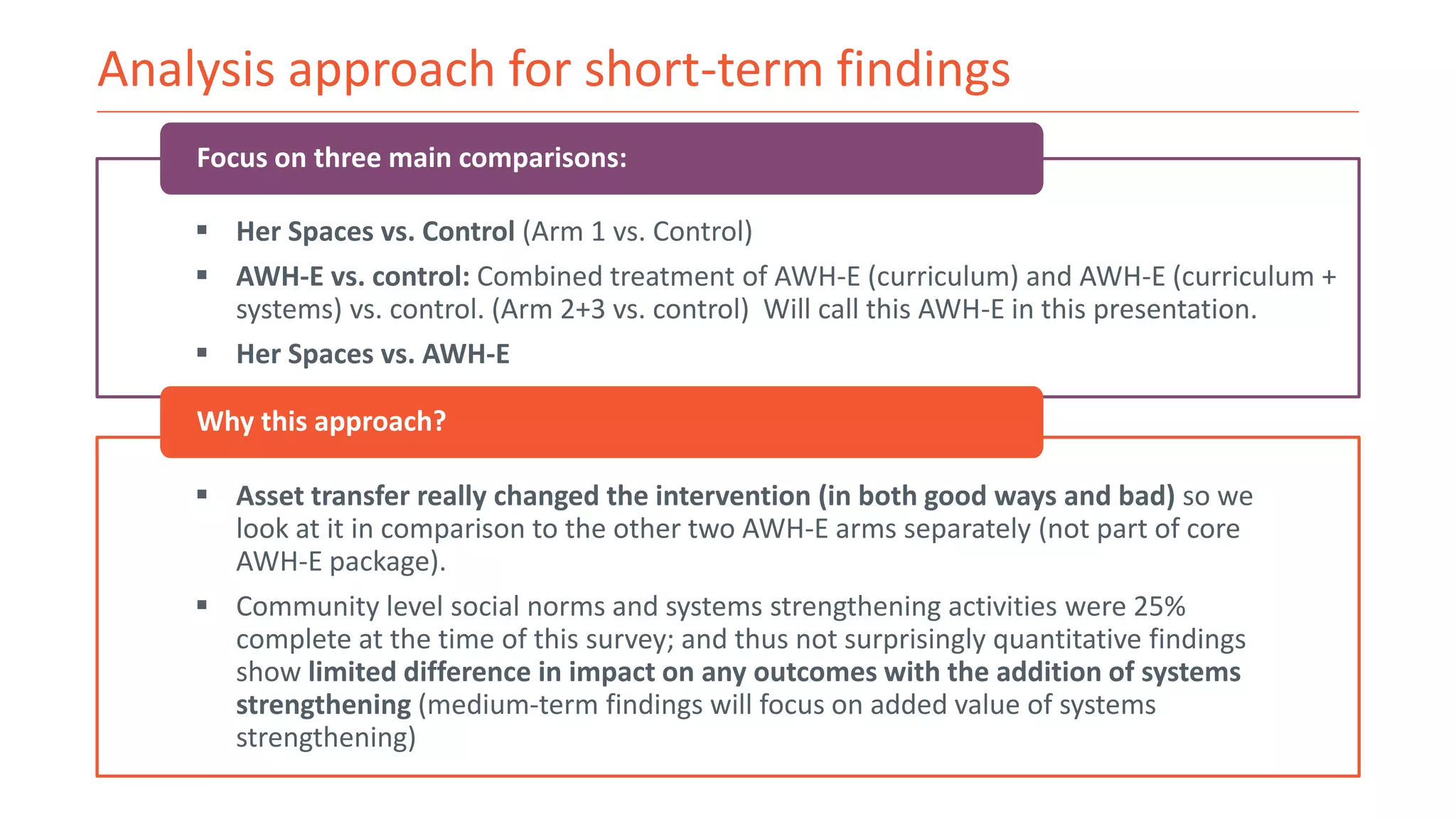

![ Undertake in-depth studies of positive and negative outlier adolescents in terms of programme

participation to better understand impact dynamics – including in urban vs rural vs pastoralist communities

Undertake inter-generational case studies to explore interactive effects of adolescent and parent

participation, and complementary role of systems strengthening to improve programming

What else would we like to do (but need co-funding for 2022/2023 data round (and beyond))

Biomarkers: STIs, cortisol, height/weight, anemia, etc. including with older cohort (for 2022 data collection)

Valuable for looking at impacts; and also for broader assessment of SRH/nutrition of this population

More outcome measurement related to mental health, nutrition and SRH

Rare opportunity to see whether impacts improve when the program launches again, building

on lessons learned from the first wave.

Could compare systems strengthening work via schools vs non-school routes (e.g. via health

extension or justice system) [although not currently in implementation plan]

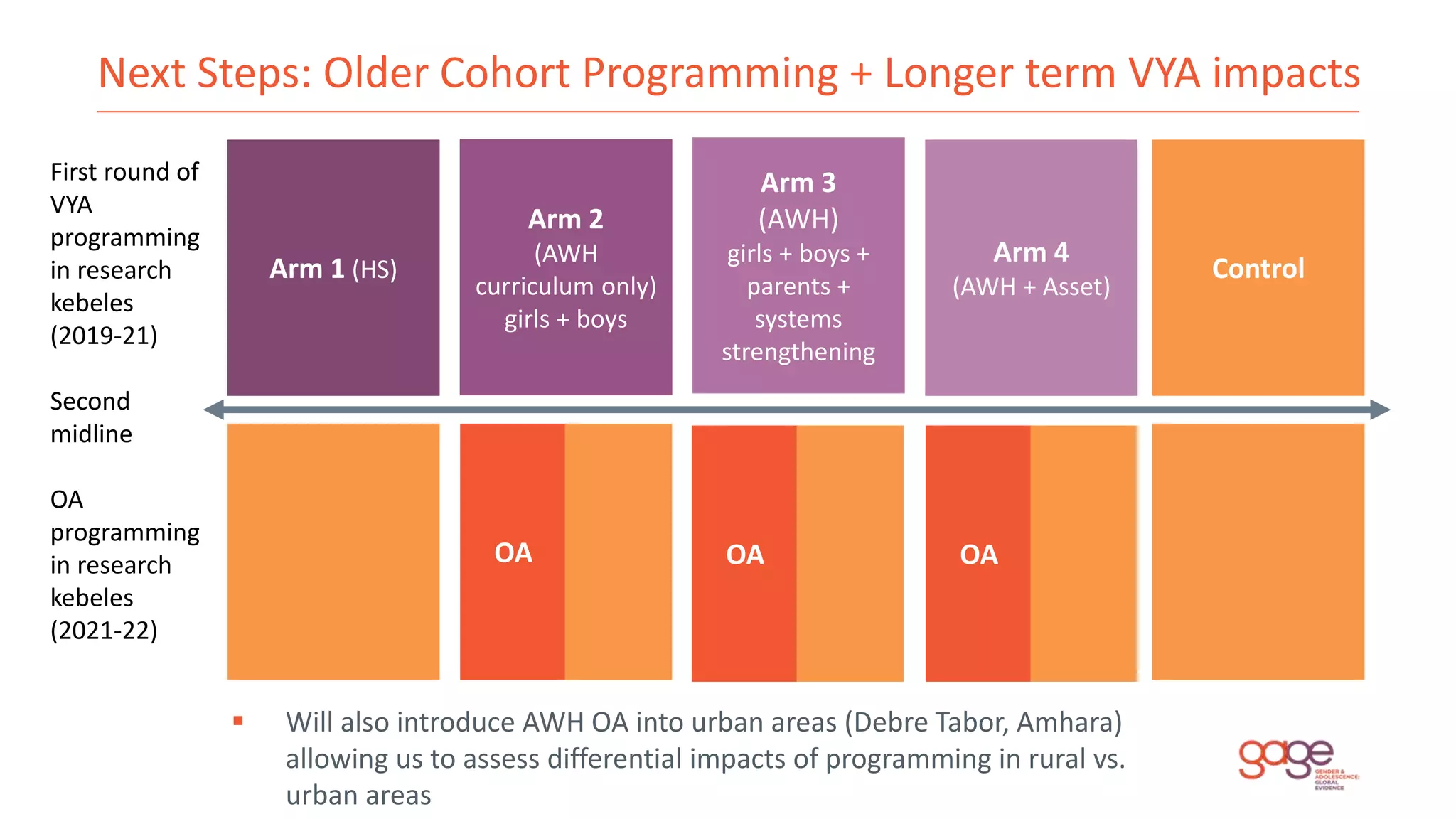

Evaluate second cohort of VYA (with improved programming)

Use lab in the field experiments

Validate new measures of gender attitudes including with two age cohorts

Add in tools such as the implicit association test

Additional innovative gender measurement

Ethnographic analyses](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbcoo5mjq1weln6wszgk-signature-bc697695088383fffb0cd6e78d2b9aa46849f09cdce57c0d5f49793eec47d99a-poli-210603083853/75/Act-With-Her-Ethiopia-Short-run-findings-on-programming-with-Very-Young-Adolescents-34-2048.jpg)