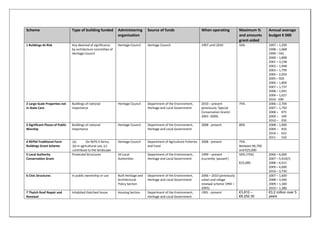

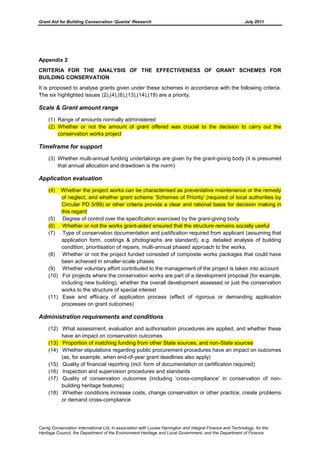

This document provides an analysis of grant aid schemes for building conservation in Ireland. It was prepared by Carrig Conservation International Ltd for the Heritage Council, Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government, and Department of Finance. The document examines seven state grant schemes, analyzes them according to 22 criteria, and provides recommendations to inform future discussions on improving grant aid efficiency and effectiveness. Key findings include that grant aid is critical for most conservation projects but achieves multiple social and economic benefits, and that schemes generally work effectively but funding availability is decreasing.