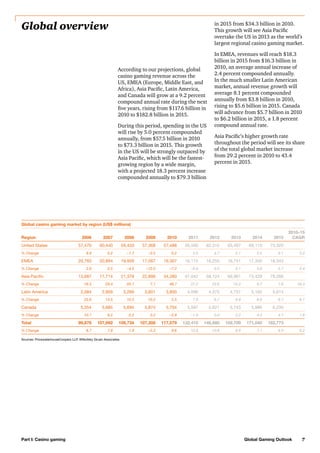

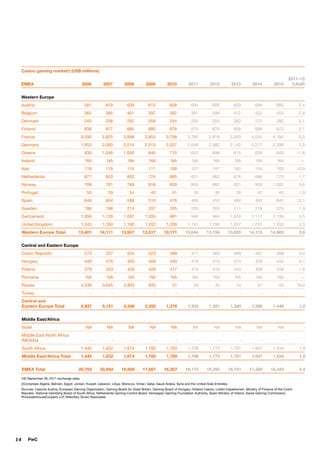

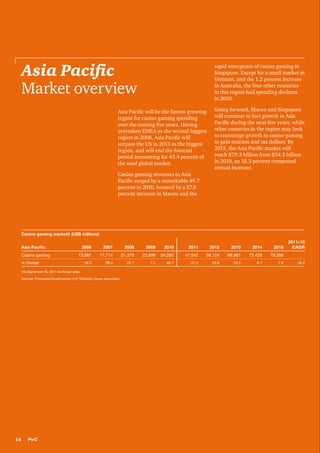

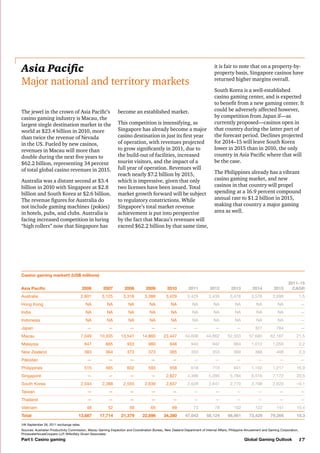

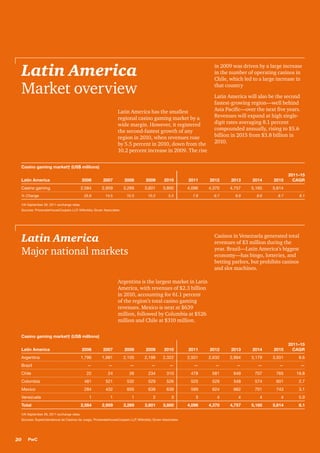

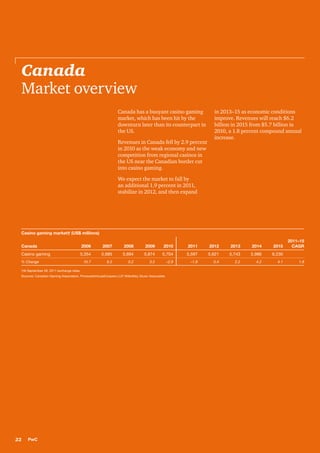

This document provides an executive summary of key trends in the global casino gaming and online gaming industries from 2010 to 2015. It finds that while global casino gaming revenues grew 9.6% in 2010, regions varied significantly with EMEA declining 7.2% and North America growing only 0.2%. In stark contrast, Asia Pacific revenues leapt 49.7% in 2010 driven by new capacity in Macau and Singapore. The document also notes that Asia Pacific is projected to surpass North America as the largest casino market by 2013. Online gaming is discussed but no revenue projections are provided due to legal and regulatory uncertainties.