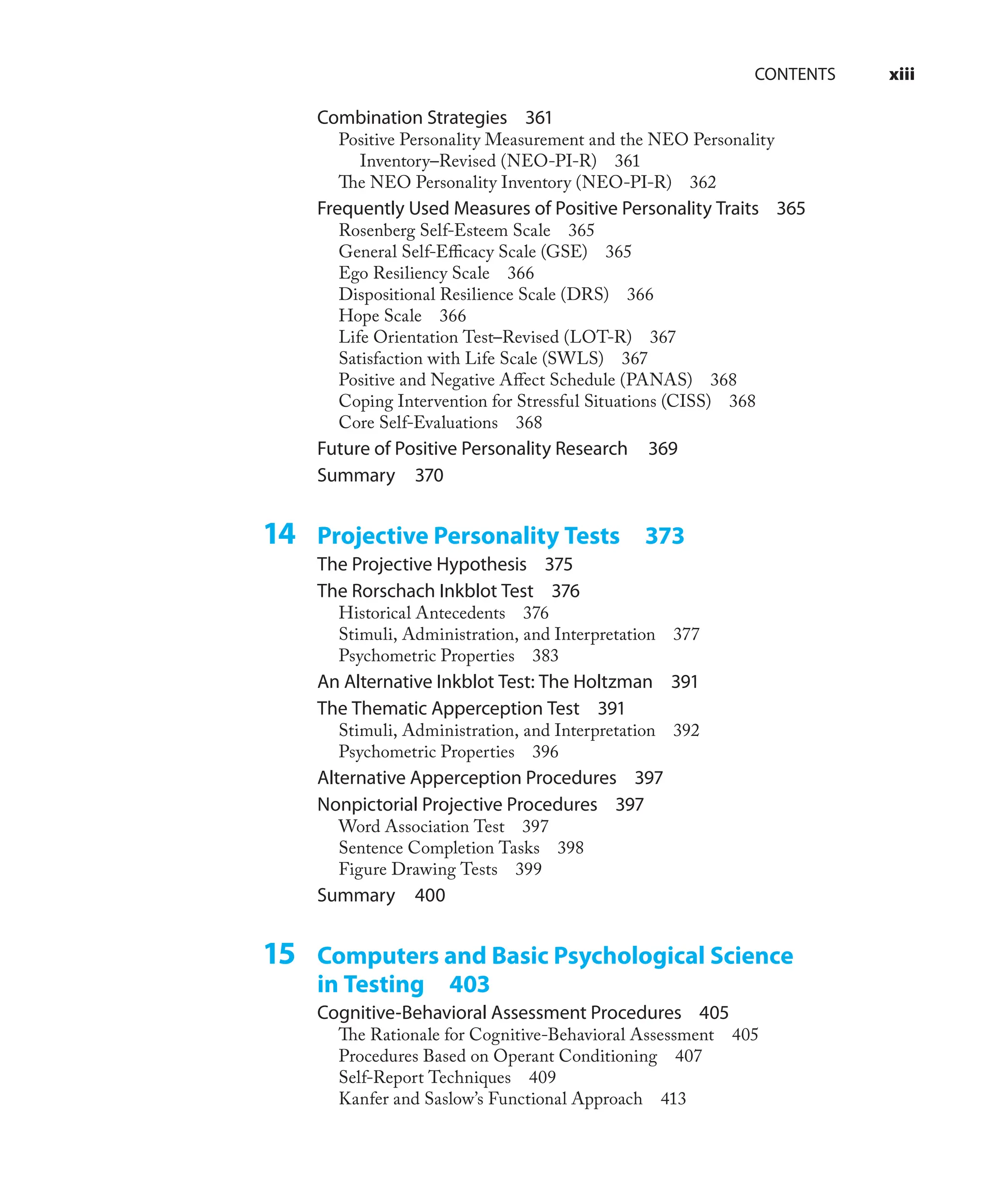

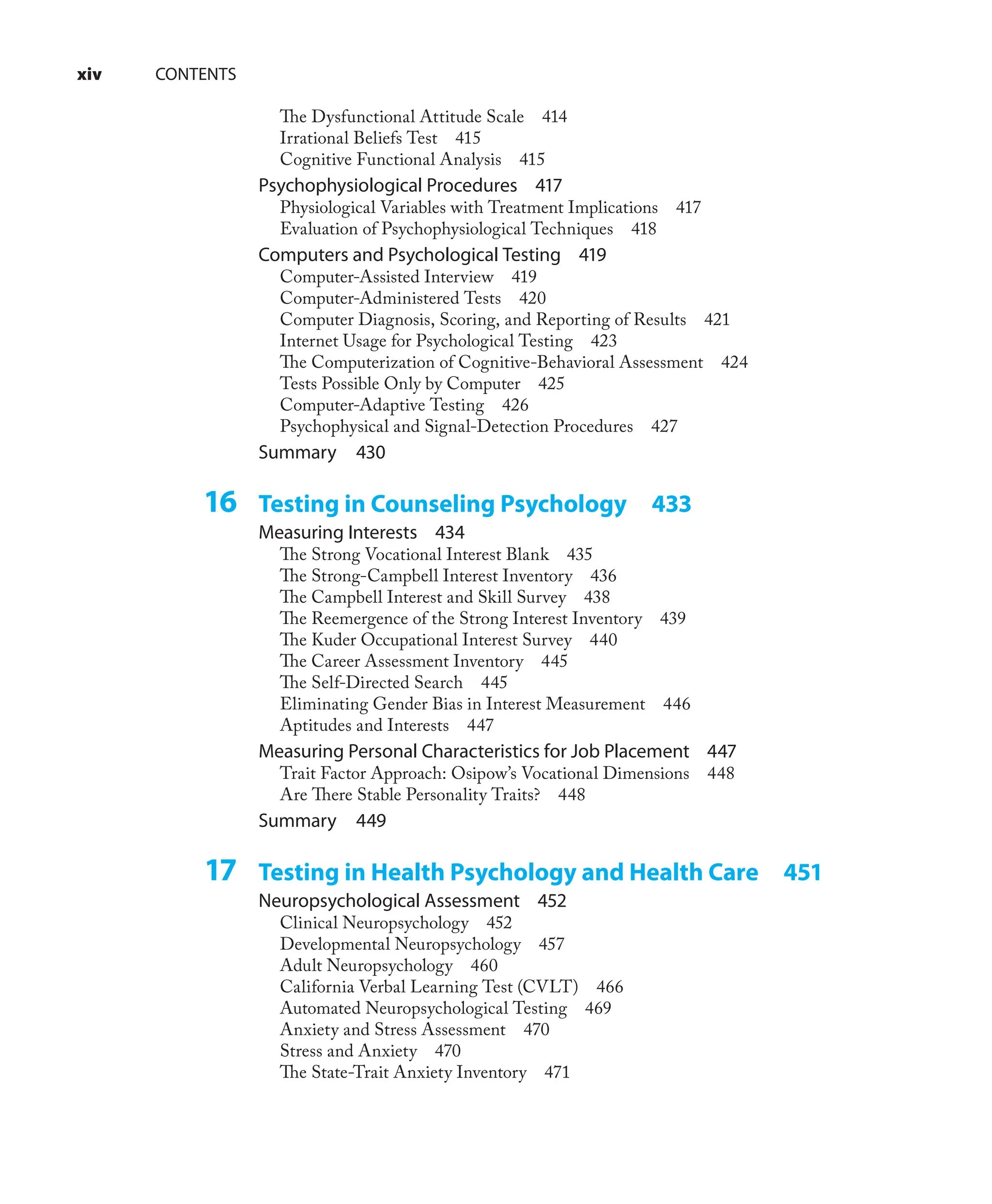

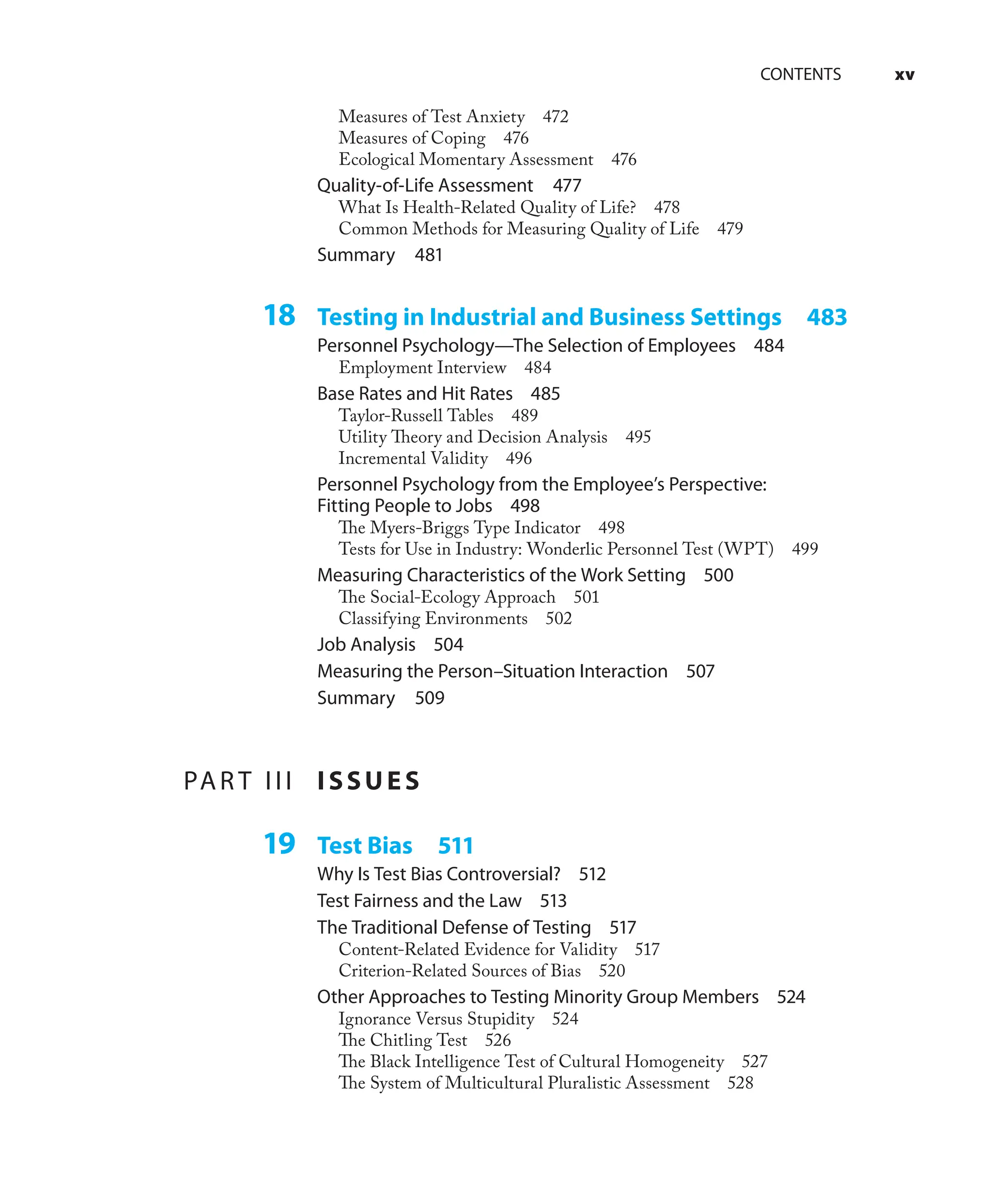

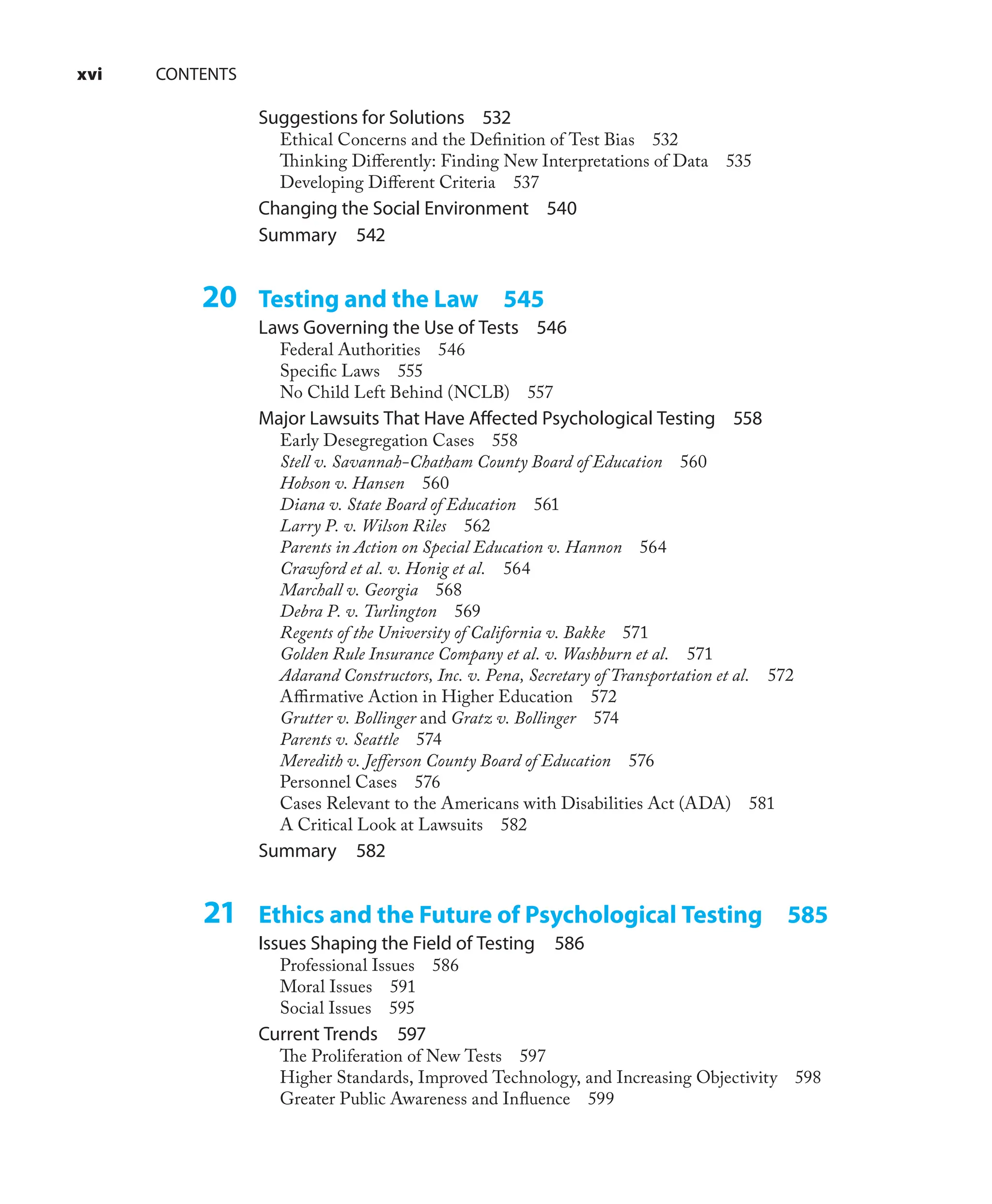

Psychological Testing Principles Applications And Issues 7th Edition Robert M Kaplan

Psychological Testing Principles Applications And Issues 7th Edition Robert M Kaplan

Psychological Testing Principles Applications And Issues 7th Edition Robert M Kaplan