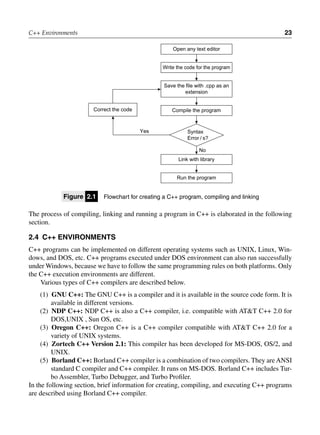

The document is a comprehensive guide to C++ programming, covering topics from language basics to advanced concepts like templates and file handling. It includes detailed explanations, examples, and exercises for each topic, making it suitable for both beginners and experienced programmers. The ebook can be downloaded from the provided website along with additional recommended titles.

![the midst of the most profound solitude, the most peaceful, the most

mysterious.

Impressed by the sight of this sad and touching picture, Catherine

leaned on the balcony of the chalet, and remained a few minutes

plunged in reverie.

Irene sat at her feet, and began to gather roses and honeysuckle to

make a bouquet.

I leaned against the door, and could not help feeling a pang of

anguish as I looked upon Madame de Fersen.

I was going to pass long days near this woman, so passionately

loved, and delicacy forbade my speaking one word of this deep and

ardent love, which circumstances recently had combined to increase.

I knew not if I was beloved, or, rather, I despaired of being loved; it

seemed to me that fate, which had brought Madame de Fersen and me

together, by the death-bed of her child, during a month of terrible

anguish, had been too tragic to end in so tender a sentiment.

I was absorbed in these sad thoughts, when Madame de Fersen

made a quick movement, as if she were aroused from a dream, and said

to me, "Pardon me, but it is so long since I breathed air so fragrant and

invigorating that I selfishly enjoy this lovely nature."

Irene divided her bouquet in two, gave one half to her mother, the

other to me, and we then started towards the house.

We reached it after a long walk, for the park was very extensive.

CHAPTER XXIV

DAYS OF SUNSHINE

THE GROVE, 10th May, 18—.[6]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/84125-241228114634-1678a52e/85/Programming-in-C-2nd-Edition-Safari-download-pdf-58-320.jpg)

![[6]Arthur, according to his custom, introduces here some

fragments from his journal, interrupted after leaving Khios, and

doubtless, resumed on his arrival at the Grove. The preceding

chapters are intended to fill the gap separating the two periods,

during which time Arthur appears to have neglected to keep his

memorandum.

CHAPTER XXV

A WOMAN IN POLITICS

Here come to an end the fragments of the journal I formerly

wrote at the Grove.

During the four months which followed Catherine's confession of

her love, and which we passed in this total isolation, my life was so

engrossed by the delights of our ever growing love that I had

neither time nor inclination to make a record of emotions so

entrancing.

Catherine confessed to me that she had felt greatly attracted to

me ever since our departure from Khios.

I asked her why she had treated me so harshly on one occasion,

when she had requested me not to see her little girl any more. She

answered that her despair at feeling herself at the mercy of the

affection I inspired, added to her jealousy and grief when she saw

me smitten by so giddy a woman as Madame de V——, had alone

decided her to put an end to the mysterious intimacy of which Irene

was the bond, however painful to her was this determination.

Later on, when she learned of the termination of my supposed

intrigue with Madame de V——, and finding that absence, instead of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/84125-241228114634-1678a52e/85/Programming-in-C-2nd-Edition-Safari-download-pdf-74-320.jpg)