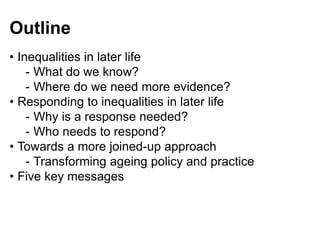

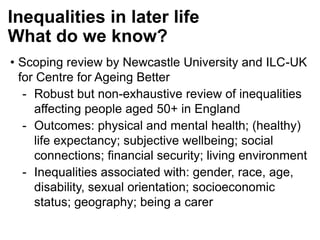

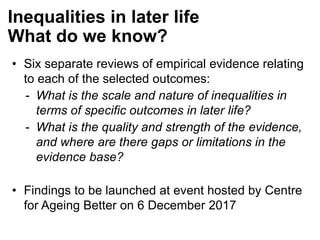

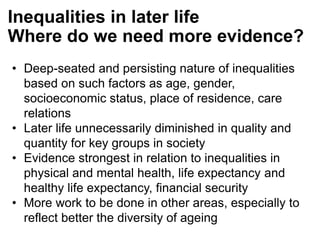

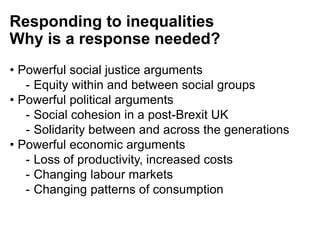

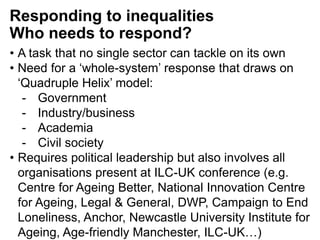

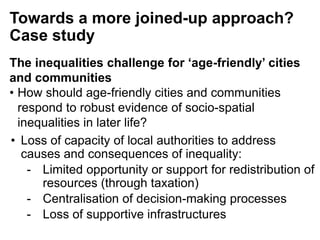

The document discusses the persistent inequalities affecting individuals aged 50+ in England, highlighting disparities in health, life expectancy, financial security, and social connections influenced by factors such as gender and socioeconomic status. It emphasizes the need for a coordinated response involving government, industry, academia, and civil society to address these inequalities effectively, particularly in 'age-friendly' cities and communities. The key takeaway is that while there is significant knowledge about these inequalities, political action and a whole-system approach are necessary to promote equitable ageing.