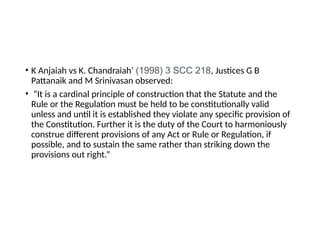

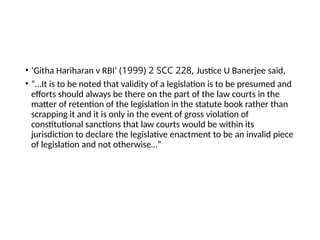

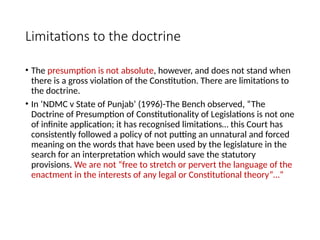

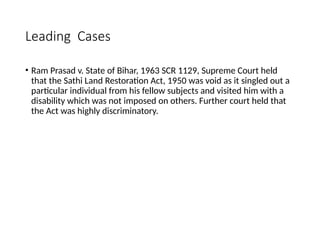

The presumption of constitutionality requires that legislation is assumed valid unless it clearly infringes fundamental rights. Courts are inclined to interpret statutes harmoniously with the constitution, favoring interpretations that uphold their validity. However, this presumption has limitations and does not apply in cases of gross constitutional violations.