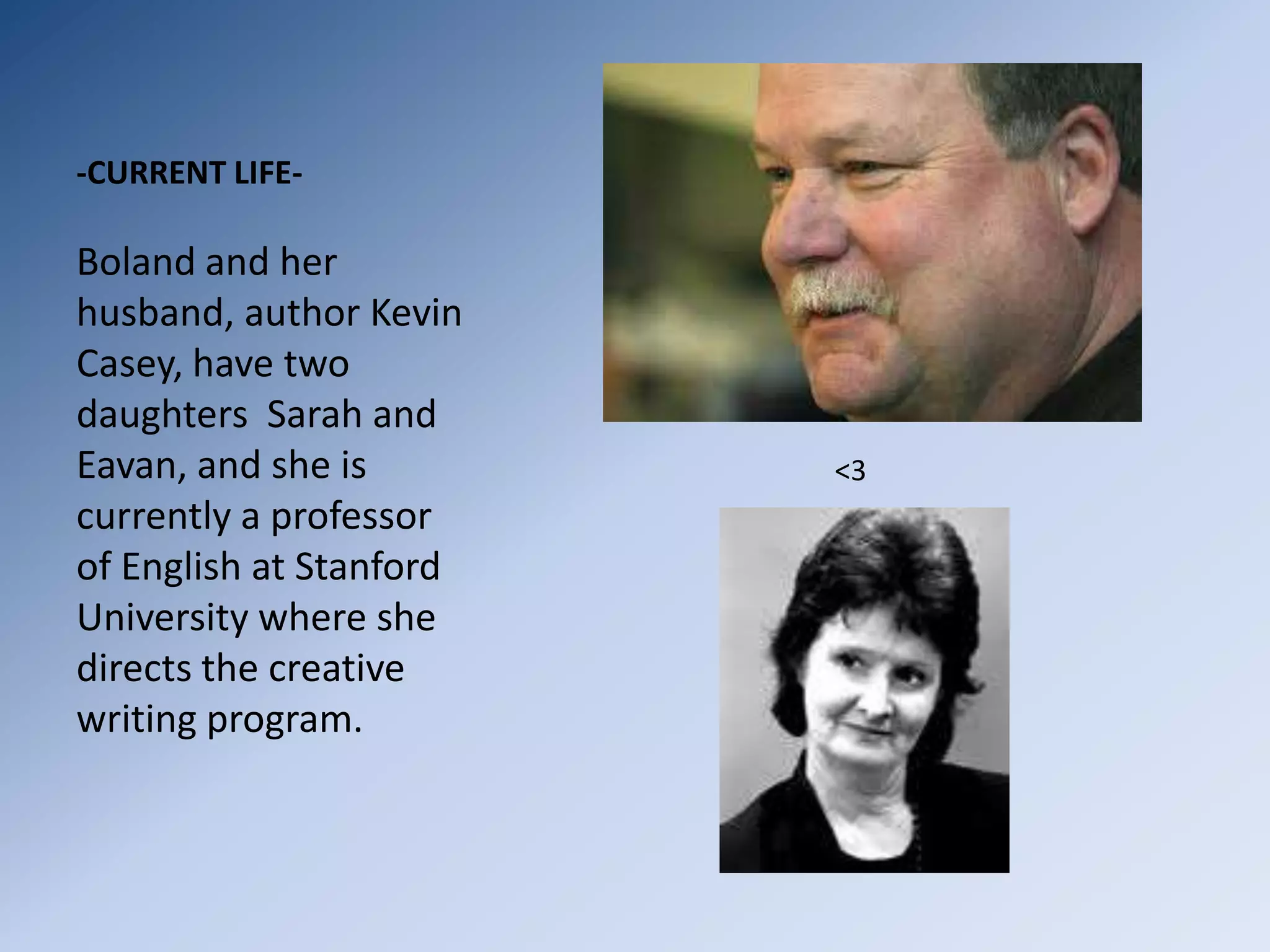

In 3 sentences or less:

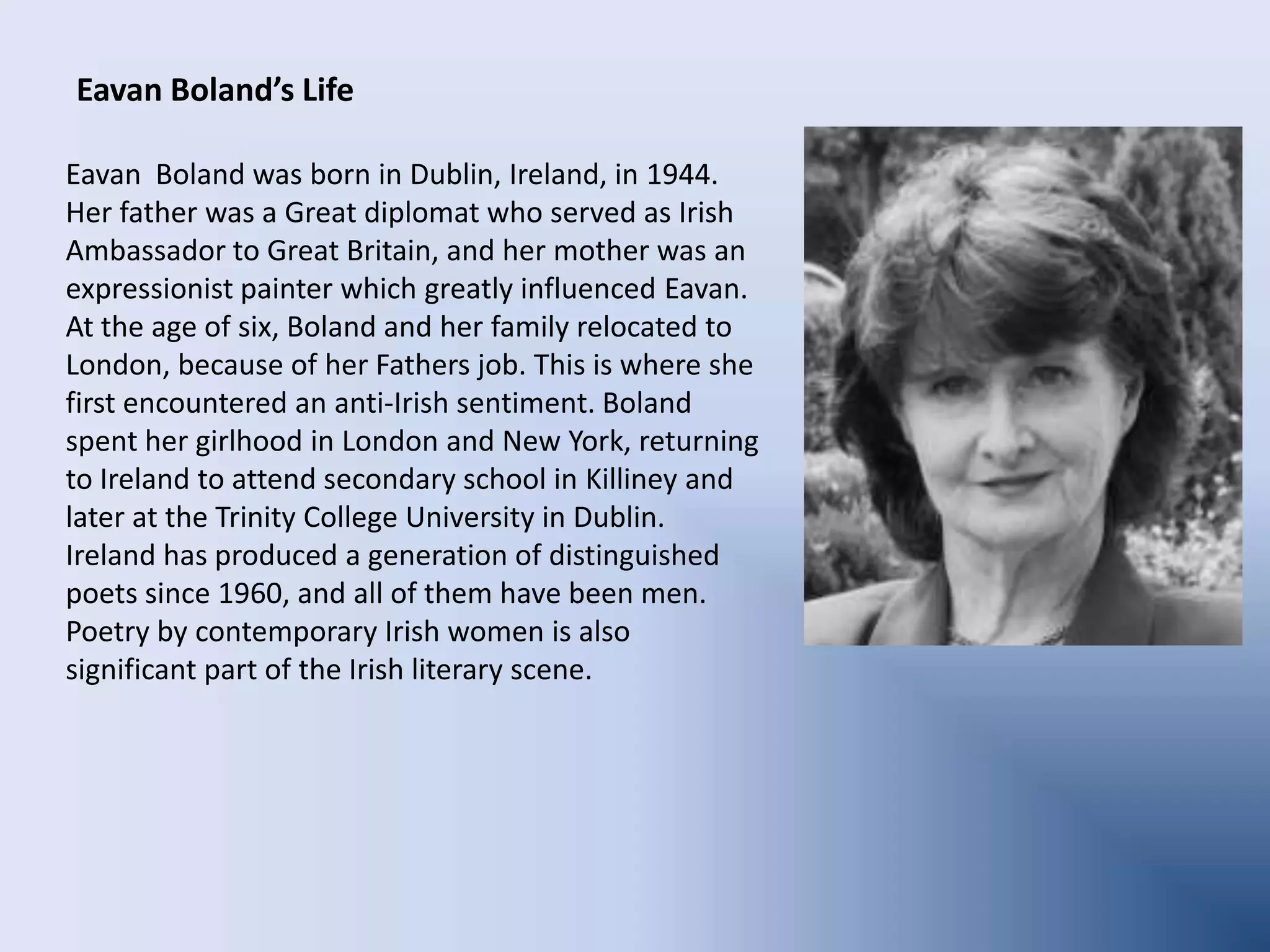

Eavan Boland's poem "Atlantis - A Lost Sonnet" reflects on the loss of her childhood home and culture when she moved from Ireland to London as a child. She compares this loss to the mythical lost city of Atlantis, suggesting that the storytellers who conceived of Atlantis did so to represent something being lost forever. The poem expresses her still feeling the loss of her old life even decades later.