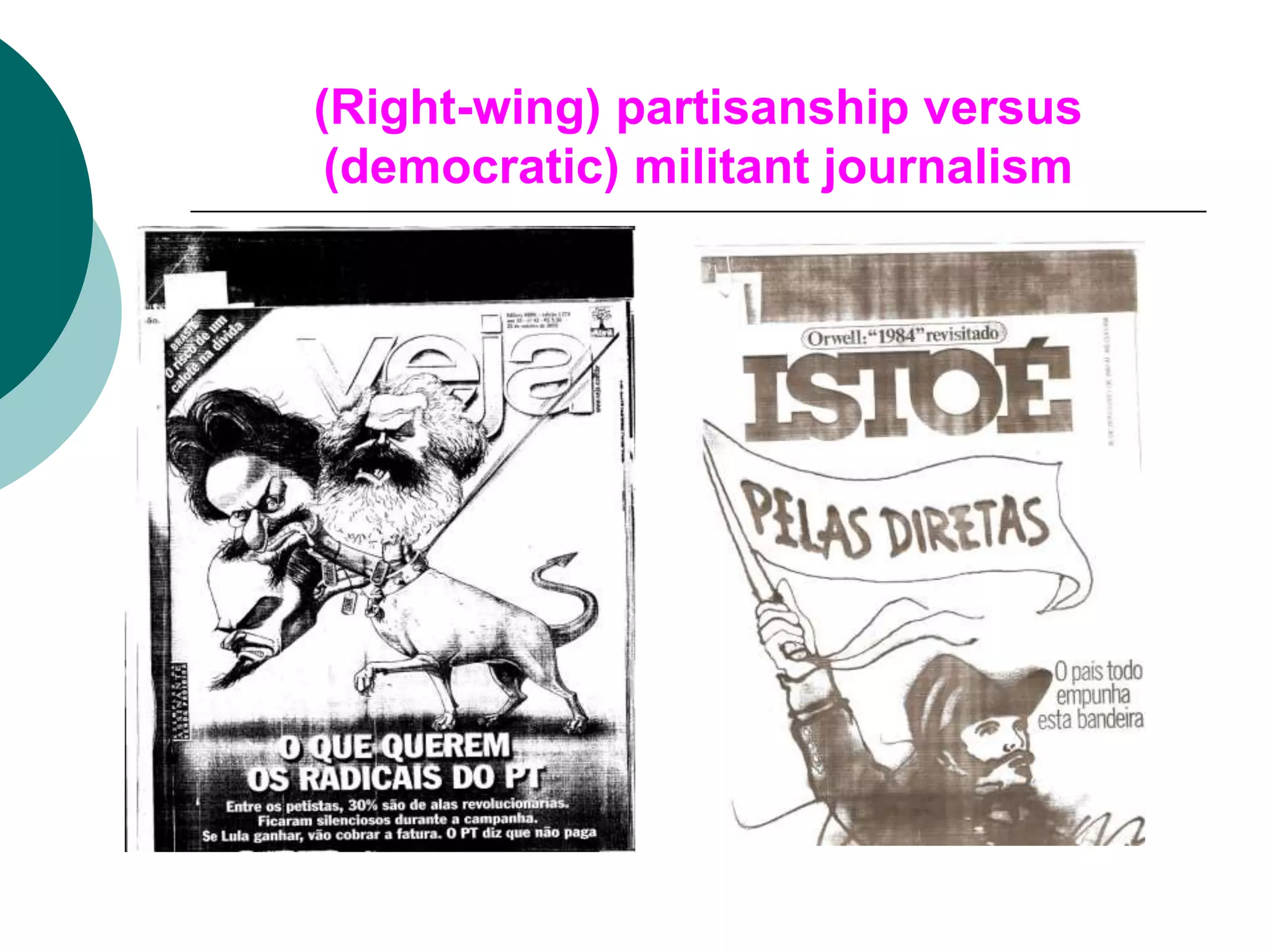

This document discusses the crisis in political journalism and civic communications. It outlines several perspectives on this crisis, including the commercialization of media leading to a decline in quality political journalism. It also discusses the changing relationship between politicians and journalists. The document examines debates around these issues and perspectives from theorists like Habermas and Baudrillard. It analyzes the role of public service broadcasting and compares models in countries like the UK, US, and Latin America. It also discusses the role of political journalists and critiques of civic journalism approaches.