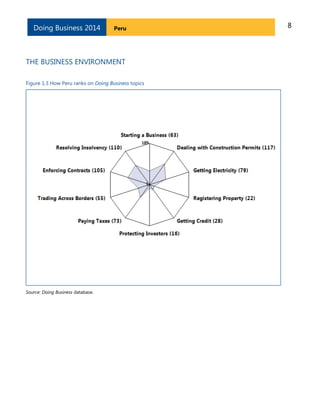

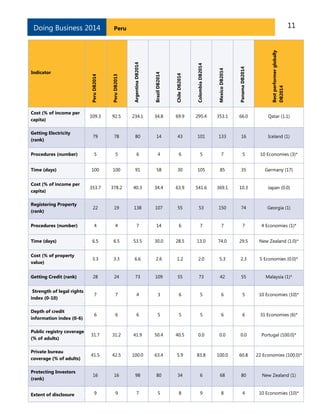

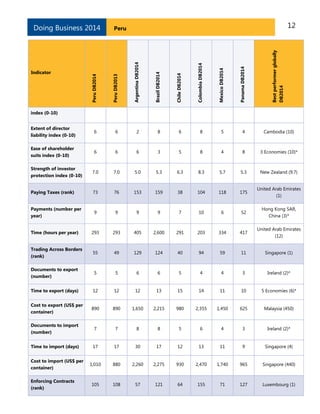

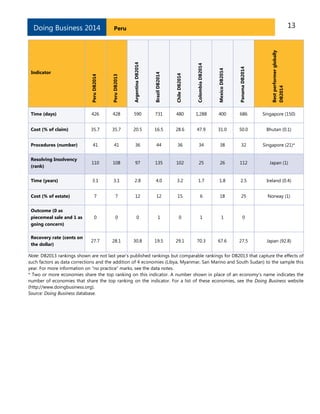

Peru ranks 42nd out of 189 economies on the ease of doing business, according to the latest World Bank report. The ranking indicates that Peru has created a relatively business-friendly regulatory environment. However, there is still room for improvement, as the country's ranking fell 3 spots compared to the previous year. Peru's overall ease of doing business score also declined slightly. Continued regulatory reforms could help Peru further strengthen its business environment and attract investment and economic growth.