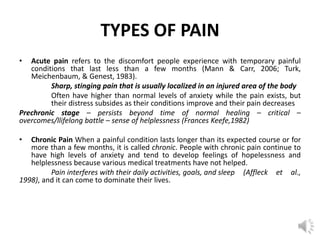

1) Pain is a complex sensory and emotional experience that involves biological, psychological, and social factors. It serves an adaptive purpose but can become chronic and debilitating.

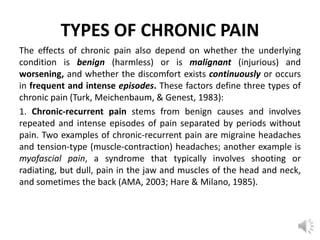

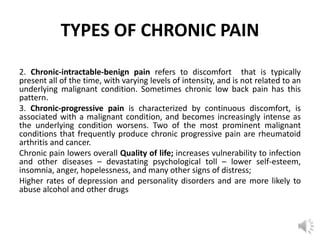

2) Chronic pain is pain that persists beyond normal healing time, often for months or years. It can be recurrent, constant, or progressive depending on its underlying cause. Chronic pain significantly impacts quality of life.

3) Self-report measures are a primary way to assess pain, including structured interviews, rating scales, and pain inventories that evaluate sensory, affective, and evaluative dimensions of the experience.