1) Strabismus is a common eye disorder characterized by misalignment of the visual axes that often appears during early visual development. However, strabismus displays significant variability in characteristics between individuals.

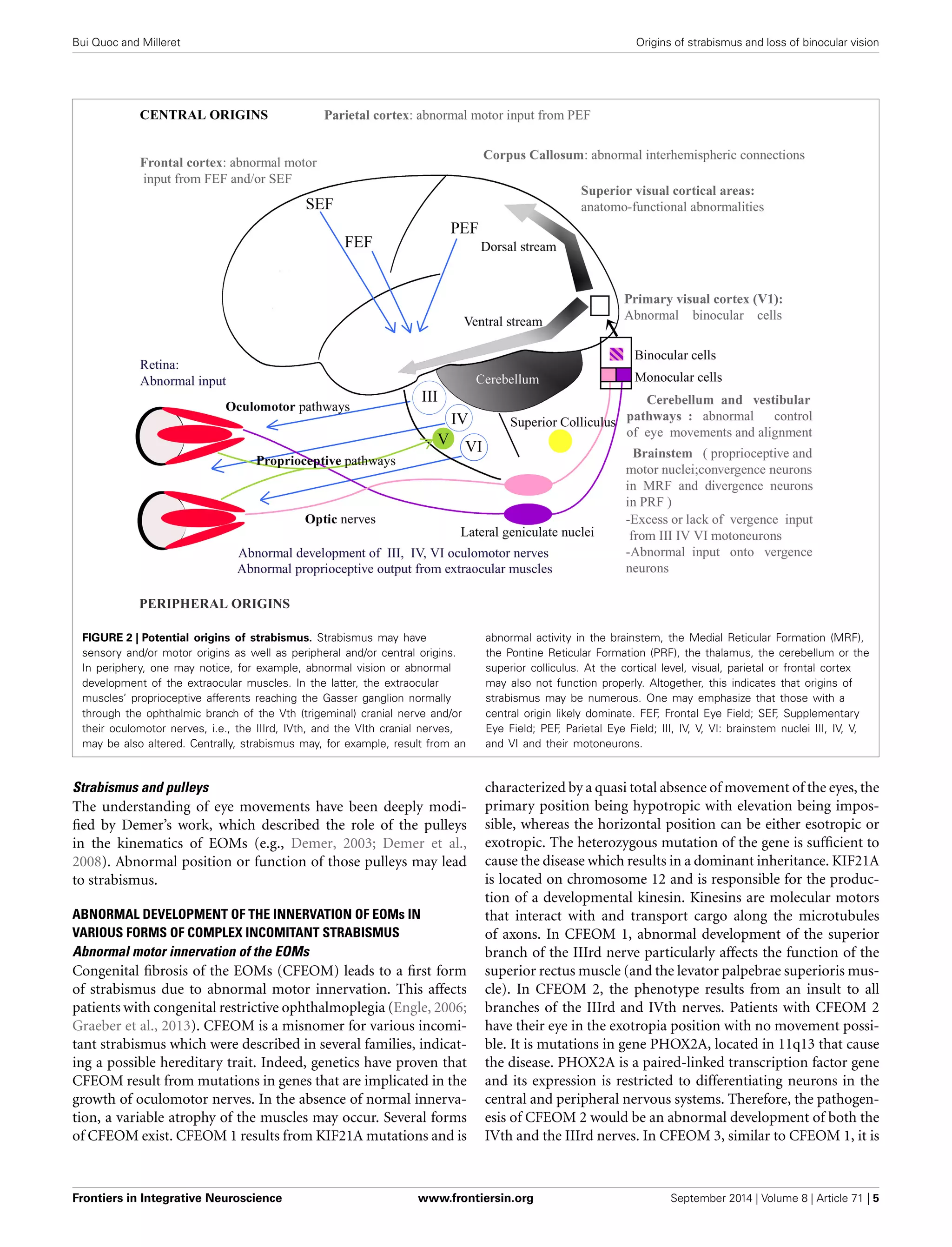

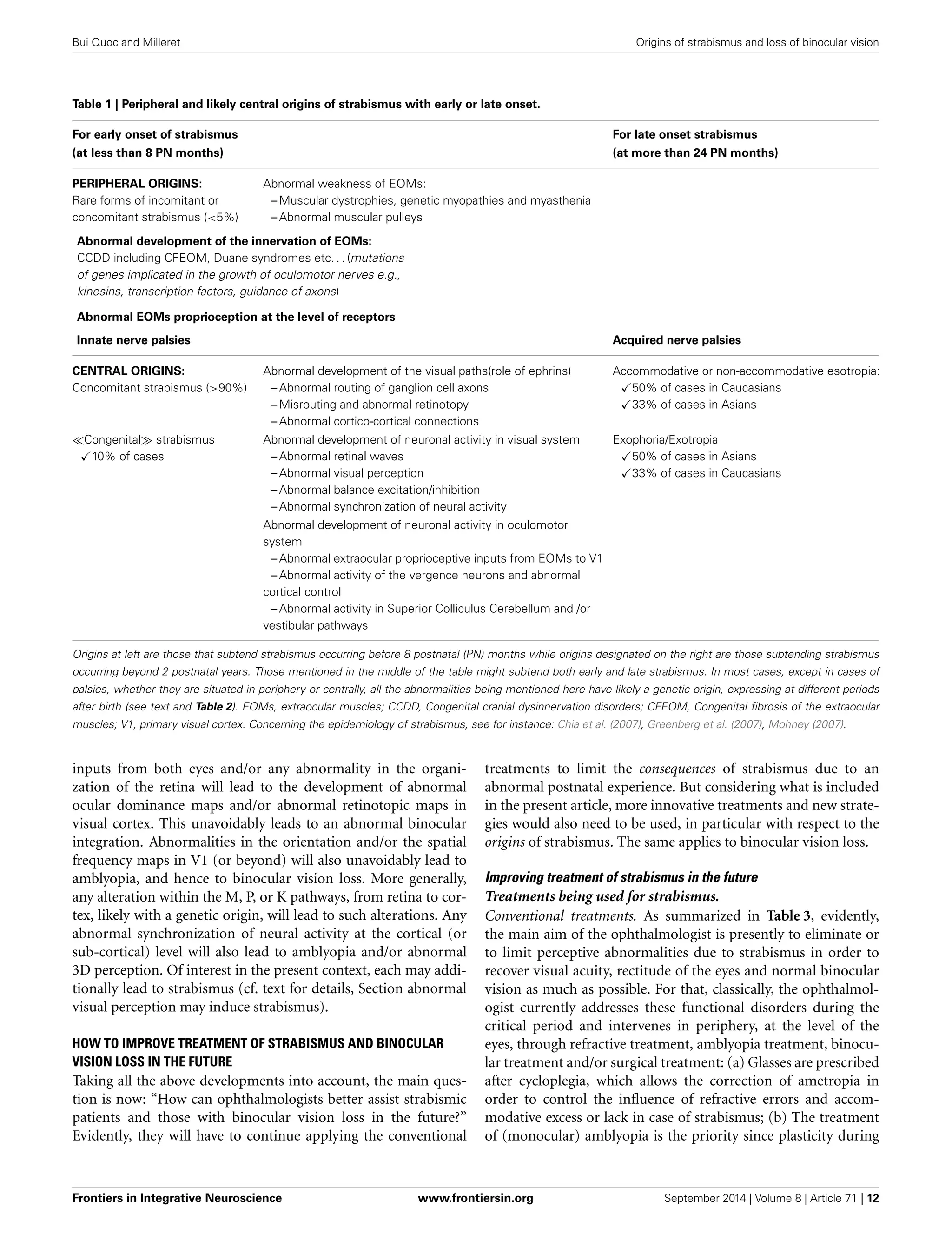

2) The authors hypothesize that this variability reflects a wide range of possible origins of strabismus, including genetic and acquired factors affecting sensory and motor systems both peripherally and centrally in the brain.

3) The paper aims to explore potential central origins of strabismus in more detail, with the goal of helping ophthalmologists better understand and treat strabismus and its impacts on binocular vision development.