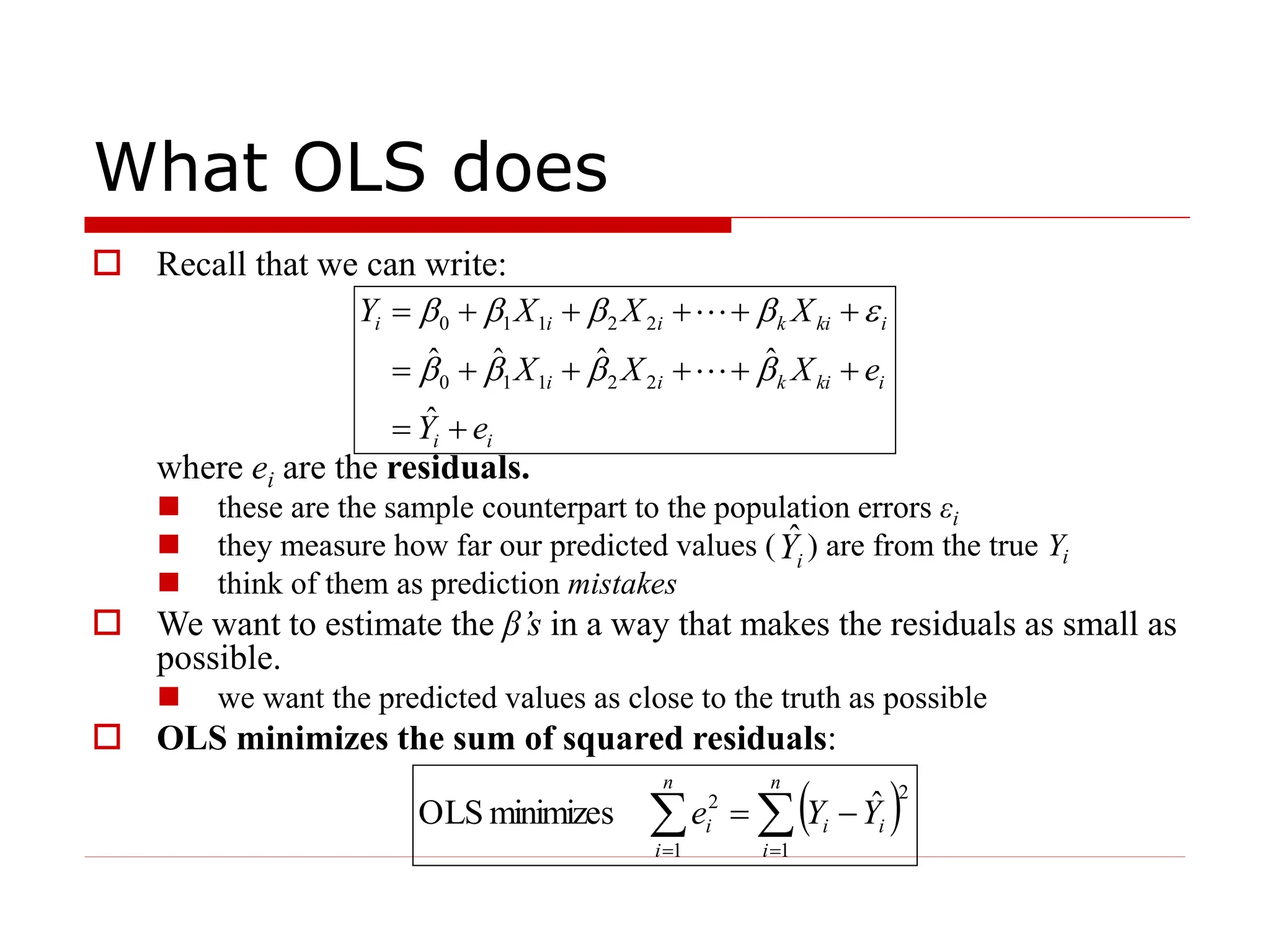

- Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimation is commonly used to estimate the coefficients in a linear regression model. OLS chooses coefficients that minimize the sum of squared residuals between predicted and actual values of the dependent variable.

- OLS finds the coefficients that make the prediction errors as small as possible. It does this by minimizing the sum of squared errors between the predicted and actual y-values.

- OLS provides unbiased estimates of the coefficients and produces estimates with the smallest possible variance, making it very widely used for linear regression analysis.