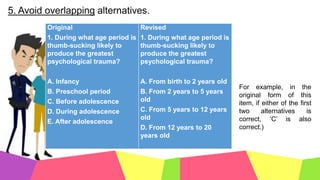

The document provides 10 rules for writing effective multiple choice questions. The rules aim to make test questions more accurate and clear. Some key points:

- Questions should test higher-order thinking like analysis and evaluation, not just recall.

- Use simple language and precise wording in questions and avoid ambiguity.

- Place most of the question words in the stem rather than the answer options.

- All distractors or incorrect answers should seem plausible to avoid obvious correct answers.

- Avoid double negatives, trick questions, or answer options of vastly different lengths that could provide unintended clues.

![• On March 1, 2002, a Notice of Termination was received by

respondent informing her that her services as Administration

Manager and Executive Assistant to the General Manager of M+W

Zander are terminated effective the same day. The respondent

was found liable for willful breach of trust and confidence in using

[her] authority and/or influence as Administrative Manager of M+W

Zander Philippines over [her] subordinate to stage a no work day

last February 1, 2002, which in turn disrupted vital operations in

the Company.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-70-320.jpg)

![• The sole ground for respondents termination by petitioners is

willful breach of trust and confidence in using [her] authority

and/or influence as Administrative Manager of ZANDER over

[her] subordinate to stage a no work day last February 1, 2002.

• Article 282 (c) of the Labor Code allows an employer to terminate

the services of an employee for loss of trust and

confidence. Certain guidelines must be observed for the

employer to terminate an employee for loss of trust and

confidence. We held in General Bank and Trust Company v.

Court of Appeals,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-73-320.jpg)

![• [L]oss of confidence should not be simulated. It should not be

used as a subterfuge for causes which are improper, illegal, or

unjustified. Loss of confidence may not be arbitrarily asserted in

the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. It must be

genuine, not a mere afterthought to justify earlier action taken in

bad faith.

• The first requisite for dismissal on the ground of loss of trust and

confidence is that the employee concerned must be one holding a

position of trust and confidence.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-74-320.jpg)

![• In the case at bar, respondent was employed as the Administration Manager and the Executive Assistant to the

General Manager. The responsibilities of the Administration Manager include:

• - To take charge of the management of Administrative personnel assigned to the head office in so far as

administrative functions are concerned (Administrative Assistants assigned to the Division heads and other

managerial positions except HRD);

• - To take charge of the over-all security for the company staff, premises, and sensitive areas; to guard

against unauthorized entry in sensitive areas (as determined by the management committee);

• - To take charge of the implementation of company rules on housekeeping, cleanliness and security for

all occupants of the Head Office in coordination with the company Division Heads and HRD;

• - To monitor attendance of all administrative personnel and enforce applicable company rules pertaining

thereto;

• - To take charge of the maintenance, upkeep and inventory of all company property within the head

office;

• - To take charge of the timely provision of supplies and equipment covered by the proper requisition documents

within the head office;

• - To take charge of traffic, tracking, and distribution of all incoming and outgoing correspondence, packages

and facsimile messages;

• - To take care of all official travel arrangements and documentation by company personnel;

• - To ensure the proper allocation of company cars assigned to the Head Office; and

• - To coordinate schedule and documentation of regular staff meetings and one-on-one meetings as required by

EVS and the Division Heads.[35] (Emphasis supplied.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-75-320.jpg)

![AMACC is an educational institution engaged in computer-based

education in the country. One of AMACCs biggest schools in the country is its

branch at Paranaque City. The petitioners were faculty members who started

teaching at AMACC on May 25, 1998. The petitioner Mercado was engaged

as a Professor 3, while petitioner Tonog was engaged as an Assistant

Professor 2. On the other hand, petitioners De Leon, Lachica and Alba, Jr.,

were all engaged as Instructor 1.[5] The petitioners executed individual

Teachers Contracts for each of the trimesters that they were engaged to teach,

with the following common stipulation:[6]

1. POSITION. The TEACHER has agreed to accept a non-tenured

appointment to work in the College of xxx effective xxx to xxx or for

the duration of the last term that the TEACHER is given a teaching

load based on the assignment duly approved by the DEAN.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-96-320.jpg)

![• For the school year 2000-2001, AMACC implemented new faculty

screening guidelines, set forth in its Guidelines on the Implementation of

AMACC Faculty Plantilla.[7] Under the new screening guidelines,

teachers were to be hired or maintained based on extensive teaching

experience, capability, potential, high academic qualifications and

research background. The performance standards under the new

screening guidelines were also used to determine the present faculty

members entitlement to salary increases. The petitioners failed to

obtain a passing rating based on the performance standards;

hence AMACC did not give them any salary increase.[8]

• Because of AMACCs action on the salary increases, the petitioners filed

a complaint with the Arbitration Branch of the NLRC on July 25, 2000, for

underpayment of wages, non-payment of overtime and overload

compensation, 13th month pay, and for discriminatory practices.[9]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-97-320.jpg)

![• On September 7, 2000, the petitioners individually received a

memorandum from AMACC, through Human Resources

Supervisor Mary Grace Beronia, informing them that with the

expiration of their contract to teach, their contract would no longer

be renewed.[10] The memorandum[11] entitled Notice of Non-

Renewal of Contract

• The petitioners amended their labor arbitration complaint to include

the charge of illegal dismissal against AMACC. In their Position

Paper, the petitioners claimed that their dismissal was illegal

because it was made in retaliation for their complaint for monetary

benefits and discriminatory practices against AMACC. The

petitioners also contended that AMACC failed to give them

adequate notice; hence, their dismissal was ineffectual.[12]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-98-320.jpg)

![THE LABOR ARBITER RULING

• On March 15, 2002, Labor Arbiter (LA) Florentino R. Darlucio declared in his

decision[14] that the petitioners had been illegally dismissed, and ordered AMACC to

reinstate them to their former positions without loss of seniority rights and to pay them

full backwages, attorneys fees and 13th month pay. The LA ruled that Article 281 of

the Labor Code on probationary employment applied to the case; that AMACC

allowed the petitioners to teach for the first semester of school year 2000-200; that

AMACC did not specify who among the petitioners failed to pass the PAST and who

among them did not comply with the other requirements of regularization, promotions

or increase in salary; and that the petitioners dismissal could not be sustained on the

basis of AMACCs vague and general allegations without substantial factual basis.[15]

• Significantly, the LA found no discrimination in the adjustments for the salary rate of

the faculty members based on the performance and other qualification which is an

exercise of management prerogative.[16] On this basis, the LA paid no heed to the

claims for salary increases.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-100-320.jpg)

![The NLRC Ruling

• On appeal, the NLRC in a Resolution dated July 18, 2005[17] denied AMACCs appeal for lack of

merit and affirmed in toto the LAs ruling. The NLRC, however, observed that the applicable law is

Section 92 of the Manual of Regulations for Private Schools (which mandates a probationary

period of nine consecutive trimesters of satisfactory service for academic personnel in the tertiary

level where collegiate courses are offered on a trimester basis), not Article 281 of the Labor Code

(which prescribes a probationary period of six months) as the LA ruled. Despite this observation,

the NLRC affirmed the LAs finding of illegal dismissal since the petitioners were terminated on the

basis of standards that were only introduced near the end of their probationary period.

• The NLRC ruled that the new screening guidelines for the school year 2000-20001 cannot be

imposed on the petitioners and their employment contracts since the new guidelines were not

imposed when the petitioners were first employed in 1998. According to the NLRC, the imposition

of the new guidelines violates Section 6(d) of Rule I, Book VI of the Implementing Rules of the

Labor Code, which provides that in all cases of probationary employment, the employer shall

make known to the employee the standards under which he will qualify as a regular employee at

the time of his engagement. Citing our ruling in Orient Express Placement Philippines v.

NLRC,[18] the NLRC stressed that the rudiments of due process demand that employees should

be informed beforehand of the conditions of their employment as well as the basis for their

advancement.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-101-320.jpg)

![The CA Ruling

• In a decision issued on November 29, 2007,[19] the CA granted AMACCs petition

for certiorari and dismissed the petitioners complaint for illegal dismissal.

• The CA ruled that under the Manual for Regulations for Private Schools, a teaching personnel in

a private educational institution (1) must be a full time teacher; (2) must have rendered three

consecutive years of service; and (3) such service must be satisfactory before he or she can

acquire permanent status.

• The CA noted that the petitioners had not completed three (3) consecutive years of service

(i.e. six regular semesters or nine consecutive trimesters of satisfactory service) and were still

within their probationary period; their teaching stints only covered a period of two (2) years and

three (3) months when AMACC decided not to renew their contracts on September 7, 2000.

• The CA effectively found reasonable basis for AMACC not to renew the petitioners contracts. To

the CA, the petitioners were not actually dismissed; their respective contracts merely expired and

were no longer renewed by AMACC because they failed to satisfy the schools standards for the

school year 2000-2001 that measured their fitness and aptitude to teach as regular faculty

members. The CA emphasized that in the absence of any evidence of bad faith on AMACCs part,

the court would not disturb or nullify its discretion to set standards and to select for regularization

only the teachers who qualify, based on reasonable and non-discriminatory guidelines.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-102-320.jpg)

![• The CA disagreed with the NLRCs ruling that the new guidelines for the school

year 2000-20001 could not be imposed on the petitioners and their

employment contracts. The appellate court opined that AMACC has the

inherent right to upgrade the quality of computer education it offers to the

public; part of this pursuit is the implementation of continuing evaluation and

screening of its faculty members for academic excellence. The CA noted that

the nature of education AMACC offers demands that the school constantly

adopt progressive performance standards for its faculty to ensure that they

keep pace with the rapid developments in the field of information technology.

• Finally, the CA found that the petitioners were hired on a non-tenured basis

and for a fixed and predetermined term based on the Teaching Contract

exemplified by the contract between the petitioner Lachica and AMACC. The

CA ruled that the non-renewal of the petitioners teaching contracts is

sanctioned by the doctrine laid down in Brent School, Inc. v. Zamora[20] where

the Court recognized the validity of contracts providing for fixed-period

employment.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-103-320.jpg)

![• The petitioners submit that the CA should not have disturbed the findings of the LA and

the NLRC that they were illegally dismissed; instead, the CA should have accorded

great respect, if not finality, to the findings of these specialized bodies as these findings

were supported by evidence on record. Citing our ruling in Soriano v. National Labor

Relations Commission,[22] the petitioners contend that in certiorari proceedings under

Rule 65 of the Rules of Court, the CA does not assess and weigh the sufficiency of

evidence upon which the Labor Arbiter and the NLRC based their conclusions. They

submit that the CA erred when it substituted its judgment for that of the Labor Arbiter

and the NLRC who were the triers of facts who had the opportunity to review the

evidence extensively.

• On the merits, the petitioners argue that the applicable law on probationary

employment, as explained by the LA, is Article 281 of the Labor Code which mandates

a period of six (6) months as the maximum duration of the probationary period unless

there is a stipulation to the contrary; that the CA should not have disturbed the LAs

conclusion that the AMACC failed to support its allegation that they did not qualify

under the new guidelines adopted for the school year 2000-2001; and that they were

illegally dismissed; their employment was terminated based on standards that were not

made known to them at the time of their engagement. On the whole, the petitioners

argue that the LA and the NLRC committed no grave abuse of discretion that the CA

can validly cite.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-104-320.jpg)

![THE CASE FOR THE RESPONDENT

• In their Comment,[23] AMACC notes that the petitioners raised no substantial

argument in support of their petition and that the CA correctly found that the

petitioners were hired on a non-tenured basis and for a fixed or predetermined

term. AMACC stresses that the CA was correct in concluding that no actual

dismissal transpired; it simply did not renew the petitioners respective

employment contracts because of their poor performance and failure to satisfy

the schools standards.

• AMACC also asserts that the petitioners knew very well that the applicable

standards would be revised and updated from time to time given the nature of

the teaching profession. The petitioners also knew at the time of their

engagement that they must comply with the schools regularization policies as

stated in the Faculty Manual. Specifically, they must obtain a passing rating

on the Performance Appraisal for Teachers (PAST) the primary instrument

to measure the performance of faculty members.

• Since the petitioners were not actually dismissed, AMACC submits that the CA

correctly ruled that they are not entitled to reinstatement, full back wages and

attorneys fees.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-105-320.jpg)

![Following this approach, our task is to determine whether the CA correctly found that

the NLRC committed grave abuse of discretion in ruling that the petitioners were

illegally dismissed.

Legal Environment in the Employment of Teachers

a. Rule on Employment on Probationary Status

• A reality we have to face in the consideration of employment on probationary status of

teaching personnel is that they are not governed purely by the Labor Code. The Labor Code

is supplemented with respect to the period of probation by special rules found in the Manual

of Regulations for Private Schools.[27] On the matter of probationary period, Section 92 of

these regulations provides:

• Section 92. Probationary Period. Subject in all instances to compliance with the

Department and school requirements, the probationary period for academic personnel

shall not be more than three (3) consecutive years of satisfactory service for those in the

elementary and secondary levels, six (6) consecutive regular semesters of satisfactory

service for those in the tertiary level, and nine (9) consecutive trimesters of satisfactory

service for those in the tertiary level where collegiate courses are offered on a

trimester basis.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-107-320.jpg)

![• The CA pointed this out in its decision (as the NLRC also did), and we confirm

the correctness of this conclusion. Other than on the period, the following

quoted portion of Article 281 of the Labor Code still fully applies:

• x x x The services of an employee who has been engaged on a probationary

basis may be terminated for a just cause when he fails to qualify as a regular

employee in accordance with reasonable standards made known by the

employer to the employee at the time of his engagement. An employee who

is allowed to work after a probationary period shall be considered a regular

employee. [Emphasis supplied]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-108-320.jpg)

![b. FIXED-PERIOD EMPLOYMENT

• The use of employment for fixed periods during the teachers probationary period is likewise an

accepted practice in the teaching profession. We mentioned this in passing in Magis Young

Achievers Learning Center v. Adelaida P. Manalo,[28] albeit a case that involved elementary, not

tertiary, education, and hence spoke of a school year rather than a semester or a trimester. We

noted in this case:

• The common practice is for the employer and the teacher to enter into a contract,

effective for one school year. At the end of the school year, the employer has the option not to

renew the contract, particularly considering the teachers performance. If the contract is not

renewed, the employment relationship terminates. If the contract is renewed, usually for another

school year, the probationary employment continues. Again, at the end of that period, the parties

may opt to renew or not to renew the contract. If renewed, this second renewal of the contract for

another school year would then be the last year since it would be the third school year of

probationary employment. At the end of this third year, the employer may now decide

whether to extend a permanent appointment to the employee, primarily on the basis of

the employee having met the reasonable standards of competence and efficiency set by

the employer. For the entire duration of this three-year period, the teacher remains under

probation. Upon the expiration of his contract of employment, being simply on probation,

he cannot automatically claim security of tenure and compel the employer to renew his

employment contract. It is when the yearly contract is renewed for the third time that Section

93 of the Manual becomes operative, and the teacher then is entitled to regular or permanent

employment status.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-109-320.jpg)

![• It is important that the contract of probationary employment specify

the period or term of its effectivity. The failure to stipulate its precise

duration could lead to the inference that the contract is binding for

the full three-year probationary period.

• We have long settled the validity of a fixed-term contract in the

case Brent School, Inc. v. Zamora[29] that AMACC

cited.Significantly, Brent happened in a school setting. Care should

be taken, however, in reading Brent in the context of this case

as Brentdid not involve any probationary employment issue; it dealt

purely and simply with the validity of a fixed-term employment under

the terms of the Labor Code, then newly issued and which does not

expressly contain a provision on fixed-term employment.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-110-320.jpg)

![ACADEMIC AND MANAGEMENT PREROGATIVE

• Last but not the least factor in the academic world, is that a school enjoys academic freedom a

guarantee that enjoys protection from the Constitution no less. Section 5(2) Article XIV of the

Constitution guarantees all institutions of higher learning academic freedom.[30]

• The institutional academic freedom includes the right of the school or college to decide and

adopt its aims and objectives, and to determine how these objections can best be attained, free

from outside coercion or interference, save possibly when the overriding public welfare calls for

some restraint. The essential freedoms subsumed in the term academic freedom encompass

the freedom of the school or college to determine for itself: (1) who may teach; (2) who may be

taught; (3) how lessons shall be taught; and (4) who may be admitted to study.[31]

• AMACCs right to academic freedom is particularly important in the present case, because of the

new screening guidelines for AMACC faculty put in place for the school year 2000-2001. We

agree with the CA that AMACC has the inherent right to establish high standards of competency

and efficiency for its faculty members in order to achieve and maintain academic

excellence. The schools prerogative to provide standards for its teachers and to determine

whether or not these standards have been met is in accordance with academic freedom that

gives the educational institution the right to choose who should teach.[32] In Pea v. National

Labor Relations Commission,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-111-320.jpg)

![• The same academic freedom grants the school the autonomy to decide

for itself the terms and conditions for hiring its teacher, subject of course

to the overarching limitations under the Labor Code. Academic freedom,

too, is not the only legal basis for AMACCs issuance of screening

guidelines. The authority to hire is likewise covered and protected by its

management prerogative the right of an employer to regulate all aspects

of employment, such as hiring, the freedom to prescribe work

assignments, working methods, process to be followed, regulation

regarding transfer of employees, supervision of their work, lay-off and

discipline, and dismissal and recall of workers.[34]

• Thus, AMACC has every right to determine for itself that it shall use fixed-

term employment contracts as its medium for hiring its teachers. It also

acted within the terms of the Manual of Regulations for Private Schools

when it recognized the petitioners to be merely on probationary status up

to a maximum of nine trimesters.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-112-320.jpg)

![The Conflict: Probationary Status

and Fixed-term Employment

• The existence of the term-to-term contracts covering the petitioners employment

is not disputed, nor is it disputed that they were on probationary status not

permanent or regular status from the time they were employed on May 25, 1998

and until the expiration of their Teaching Contracts on September 7, 2000. As the

CA correctly found, their teaching stints only covered a period of at least seven (7)

consecutive trimesters or two (2) years and three (3) months of service. This

case, however, brings to the fore the essential question of which, between

the two factors affecting employment, should prevail given AMACCs

position that the teachers contracts expired and it had the right not to renew

them. In other words, should the teachers probationary status be disregarded

simply because the contracts were fixed-term?

• The provision on employment on probationary status under the Labor Code[35] is a

primary example of the fine balancing of interests between labor and

management that the Code has institutionalized pursuant to the underlying intent

of the Constitution.[36]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-113-320.jpg)

![• On the one hand, employment on probationary status affords management the chance to

fully scrutinize the true worth of hired personnel before the full force of the security of

tenure guarantee of the Constitution comes into play.[37] Based on the standards set at

the start of the probationary period, management is given the widest opportunity during

the probationary period to reject hirees who fail to meet its own adopted but reasonable

standards.[38] These standards, together with the just[39] and authorized causes[40] for

termination of employment the Labor Code expressly provides, are the grounds available

to terminate the employment of a teacher on probationary status.

• For example, the school may impose reasonably stricter attendance or report compliance

records on teachers on probation, and reject a probationary teacher for failing in this

regard, although the same attendance or compliance record may not be required for a

teacher already on permanent status. At the same time, the same just and authorizes

causes for dismissal under the Labor Code apply to probationary teachers, so that they

may be the first to be laid-off if the school does not have enough students for a given

semester or trimester. Termination of employment on this basis is an authorized cause

under the Labor Code.[41]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-114-320.jpg)

![• Labor, for its part, is given the protection during the probationary period of knowing the

company standards the new hires have to meet during the probationary period, and to be

judged on the basis of these standards, aside from the usual standards applicable to

employees after they achieve permanent status. Under the terms of the Labor Code, these

standards should be made known to the teachers on probationary status at the start of their

probationary period, or at the very least under the circumstances of the present case, at the

start of the semester or the trimester during which the probationary standards are to be

applied.

• Of critical importance in invoking a failure to meet the probationary standards, is that the

school should show as a matter of due process how these standards have been

applied. This is effectively the second notice in a dismissal situation that the law requires as a

due process guarantee supporting the security of tenure provision,[42] and is in furtherance,

too, of the basic rule in employee dismissal that the employer carries the burden of justifying a

dismissal.[43] These rules ensure compliance with the limited security of tenure guarantee the

law extends to probationary employees.[44]

• When fixed-term employment is brought into play under the above probationary period rules,

the situation as in the present case may at first blush look muddled as fixed-term employment

is in itself a valid employment mode under Philippine law and jurisprudence.[4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-115-320.jpg)

![• AMACC, by its submissions, admits that it did not renew the petitioners contracts

because they failed to pass the Performance Appraisal System for Teachers (PAST) and

other requirements for regularization that the school undertakes to maintain its high

academic standards.[47] The evidence is unclear on the exact terms of the standards,

although the school also admits that these were standards under the Guidelines on the

Implementation of AMACC Faculty Plantilla put in place at the start of school year 2000-

2001.

• While we can grant that the standards were duly communicated to the petitioners and

could be applied beginning the 1sttrimester of the school year 2000-2001, glaring and

very basic gaps in the schools evidence still exist. The exact terms of the standards were

never introduced as evidence; neither does the evidence show how these standards

were applied to the petitioners.[48] Without these pieces of evidence (effectively, the

finding of just cause for the non-renewal of the petitioners contracts), we have nothing to

consider and pass upon as valid or invalid for each of the petitioners. Inevitably, the non-

renewal (or effectively, the termination of employment of employees on probationary

status) lacks the supporting finding of just cause that the law requires and, hence, is

illegal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-119-320.jpg)

![• In this light, the CA decision should be reversed. Thus, the LAs decision,

affirmed as to the results by the NLRC, should stand as the decision to be

enforced, appropriately re-computed to consider the period of appeal and

review of the case up to our level.

• Given the period that has lapsed and the inevitable change of circumstances

that must have taken place in the interim in the academic world and at AMACC,

which changes inevitably affect current school operations, we hold that - in lieu

of reinstatement - the petitioners should be paid separation pay computed on a

trimestral basis from the time of separation from service up to the end of the

complete trimester preceding the finality of this Decision.[49] The separation pay

shall be in addition to the other awards, properly recomputed, that the LA

originally decreed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-120-320.jpg)

![Even granting arguendo that a protest may be properly

lodged against a designation, petitioner Tapispisan’s protest against

the designation of respondents Rumbaoa and Teves on the ground

that she is more qualified must still fail. In her

4th Indorsement[22] dated August 10, 1995, respondent Benzon, as

Principal IV, Coordinating Principal of the South District, clarified that

respondent Teves was considered for designation as OIC-Principal

of Don Carlos Elementary School because of her orientation and

training. Aside from occupying the position of Master Teacher II,

respondent Teves carried with her three years of work experience

as officer-in-charge of the same school. Respondent Benzon,

likewise, justified the designation of respondent Rumbaoa as OIC-

Head Teacher of P. Villanueva Elementary School stating that she

was qualified there for having been duly appointed Head Teacher III

effective March 15, 1995. Further, she ranked No. 2 in the Division

List of Promotables for the school year 1993-1994.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-153-320.jpg)

![Clearly, the designation of respondents Rumbaoa and Teves

was well within the prerogative of the said respondents DECS

officials. It behooves the Court to refrain from unduly interfering with

the exercise of such administrative prerogative. After all, it is well

settled that administrative decisions on matters within the jurisdiction

of administrative bodies are entitled to respect and can only be set

aside on proof of grave abuse of discretion, fraud or error of

law.[25] None of these vices has been shown as having attended the

designation of respondents Rumbaoa and Teves.

In fine, the appellate court committed no reversible error when

it affirmed the resolutions of the CSC dismissing the protest filed by

petitioner Tapispisan and upholding the designation of respondent

Rumbaoa as OIC-Head Teacher of P. Villanueva Elementary School

and respondent Teves as OIC-Principal of Don Carlos Elementary

School.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-154-320.jpg)

![In her position paper,[4] respondent claimed that her

termination violated the provisions of her employment

contract, and that the alleged abolition of the position of

Principal was not among the grounds for termination by an

employer under Article 282[5] of the Labor Code.

She further asserted that petitioner infringed Article

283[6] of the Labor Code, as the required 30-day notice to

the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) and to

her as the employee, and the payment of her separation pay

were not complied with. She also claimed that she was

terminated from service for the alleged expiration of her

employment, but that her contract did not provide for a fixed

term or period. She likewise prayed for the payment of her

13th month pay under Presidential Decree (PD) No. 851.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-162-320.jpg)

![On December 3, 2003, Labor Arbiter (LA) Renell Joseph R.

dela Cruz rendered a Decision[8] dismissing the complaint for illegal

dismissal, including the other claims of respondent, for lack of merit,

except that it ordered the payment of her 13th month pay in the

amount of P3,750.00.

On appeal, on October 28, 2005, the National Labor Relations

Commission (NLRC), Third Division,[9] in its Decision[10] dated

October 28, 2005, reversed the Arbiters judgment. Petitioner was

ordered to reinstate respondent as a teacher, who shall be credited

with one-year service of probationary employment, and to pay her

the amounts ofP3,750.00 and P325,000.00 representing her

13th month pay and backwages, respectively. Petitioners motion for

reconsideration was denied in the NLRCs Resolution[11] dated

January 31, 2006.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-163-320.jpg)

![Procedural Due

Process

• First notice: Notice to Explain (NTE) or order to show

cause.

- specifies the ground/s for termination,

- opportunity within which to explain his side.

• Hearing or formal investigation.

- is given opportunity to respond to the charge,

present his evidence or rebut the evidence

presented against him.

• Second notice: Notice of decision. A written notice of

termination served on the employee indicating that upon

due consideration of all the circumstances, grounds have

been established to justify his termination. (See Art.

277[b] and Sec 2, Rule I, Book VI, IRR)

twin-notice

and hearing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-172-320.jpg)

![2. Gross Insubordination

Elements: (a) employee’s assailed conduct must be

willful or intentional; (b) willfulness characterized by

wrongful or perverse attitude; (c) the order violated

must be reasonable, lawful and made known to the

employee; and (d) the order must pertain to the

duties which the employee has been engaged to

discharge.

This is a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of

the Rules of Court filed by petitioner Rebecca T. Arquero against

public respondents Edilberto C. De Jesus (De Jesus), in his

capacity as Secretary of Education, Dr. Paraluman Giron (Dr.

Giron), Department of Education (DepEd) Director, Regional Office

IV-MIMAROPA, Dr. Eduardo Lopez (Lopez), Schools Division

Superintendent, Puerto Princesa City, and private respondent

Norma Brillantes. Petitioner assails the Court of Appeals (CA)

Decision[1] dated December 15, 2004 and Resolution[2] dated May](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-192-320.jpg)

![On December 1, 1994, Director Rexs successor, Pedro B. Trinidad placed all

satellite schools of the PINS under the direct supervision of the Schools Division

Superintendent for Palawan effective January 1, 1995.[10] This directive was later

approved by the DepEd in September 1996. Petitioner was instructed to turn

over the administration and supervision of the PINS branches or units.[11] In another

memorandum, Schools Division Superintendent Portia Gesilva was designated as OIC

of the PINS. These events prompted different parties to institute various actions

restraining the enforcement of the DepEd orders.

On May 14, 2002, then DECS Undersecretary Jaime D. Jacob issued an

Order[14] addressed to Dr. Giron, OIC, DepEd Regional Office No. 4, stating that there

being no more legal impediment to the integration, he ordered that the secondary

schools integrated with the PNS be under the direct administrative management and

supervision of the schools division superintendents of the divisions of Palawan and

Puerto Princesa City, as the case may be, according to their geographical and political

boundaries.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-195-320.jpg)

![On September 19, 2002, Dr. Giron withdrew the designation of petitioner as OIC of the PINS, enjoining

her from submitting to the Regional Office all appointments and personnel movement involving the PNS and the

satellite schools. On November 7, 2002, petitioner appealed to the Civil Service Commission assailing the

withdrawal of her designation as OIC of the PINS.[16]

On September 18, 2003, Dr. Giron filed a formal charge[19] against petitioner who continued to defy the

orders issued by the Regional Office relative to the exercise of her functions as OIC of the PINS despite the

designation of private respondent as such. The administrative complaint charged petitioner with grave

misconduct, gross insubordination and conduct prejudicial to the best interest of the service. Petitioner was also

preventively suspended for ninety (90) days.[20]

On October 2, 2003, petitioner filed the Petition for Quo Warranto (A legal proceeding during which an

individual's right to hold an office or governmental privilege is challenged) with Prayer for Issuance of Temporary

Restraining Order and/or Injunctive Writ[21] before the RTC of Palawan[22] against public and private respondents.

The case was docketed as Civil Case No. 3854. Petitioner argued that the designation of private respondent

deprived her of her right to exercise her function and perform her duties in violation of her right to security of

tenure. Considering that petitioner was appointed in a permanent capacity, she insisted that private respondents

designation as OIC of the PNS is null and void there being no vacancy to the position.

On October 6, 2003, the Executive Judge issued a 72-Hour TRO[24] enjoining and restraining private

respondent from assuming the position of OIC and performing the functions of the Office of the Principal of the

PNS; and restraining public respondents from giving due course or recognizing the assailed designation of

private respondent. The RTC later issued the writ of preliminary injunction.[25]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-196-320.jpg)

![On June 14, 2004, the RTC rendered a Judgment by Default,[28] the dispositive portion of

which reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered and by preponderance of evidence, judgment is hereby

rendered:

1. Declaring petitioner Rebecca T. Arquero as the lawful Principal and Head of the

Palawan Integrated National High School who is lawfully entitled to manage the operation and

finances of the school subject to existing laws;

2. Declaring the formal charge against petitioner, the preventive suspension, the

investigating committee, the proceedings therein and any orders, rulings, judgments and

decisions that would arise there from as null, void and of no effect;

3. Ordering respondent Norma Brillantes, or any person acting in her behalf, to

cease and desist from assuming and exercising the functions of the Office of the Principal of

Palawan Integrated National High School, and respondents Edilberto C. De Jesus,

Paraluman R. Giron and Eduardo V. Lopez, or any person acting in their behalf, from giving

due course or recognizing the same; and

4. Making the writ of preliminary injunction issued in this case permanent.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-197-320.jpg)

![CA held that the PINS and its satellite schools remain under the complete administrative

jurisdiction of the DepEd and not transferred to the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority

(TESDA). It also explained that by providing for a distinct position of VSS with a higher qualification,

specifically chosen and appointed by the DepEd Secretary that is separate from the school head of the PNS

offering general secondary education program, RA 6765 intended that the functions of a VSS and School

Principal of PNS be discharged by two separate persons.[33] The CA added that if we follow the RTC

conclusion, petitioner would assume the responsibilities and exercise the functions of a division schools

superintendent without appointment and compliance with the qualifications required by law.[34] The appellate

court likewise held that petitioner failed to establish her clear legal right to the position of OIC of the PINS as

she was not appointed but merely designated to the position in addition to her functions as incumbent

school principal of the PNS.[35]

The next question to be resolved is whether petitioner has the right to the contested public office

and to oust private respondent from its enjoyment. We answer in the negative.

In quo warranto, the petitioner who files the action in his name must prove that he is entitled to the

subject public office. In other words, the private person suing must show a clear right to the contested

position.[46] Otherwise, the person who holds the same has a right to undisturbed possession and the action

for quo warranto may be dismissed.[47] It is not even necessary to pass upon the right of the defendant who,

by virtue of his appointment, continues in the undisturbed possession of his office.[48]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-198-320.jpg)

![• On November 17, 1994, at around 1:30 in the afternoon inside St. Joseph

Colleges [SJCs] premises, the class to which [respondent Jayson Val Miranda]

belonged was conducting a science experiment about fusion of sulphur powder and

iron fillings under the tutelage of [petitioner] Rosalinda Tabugo, she being the

subject teacher and employee of [petitioner] SJC. The adviser of [Jaysons] class is

x x x Estefania Abdan.

• Tabugo left her class while it was doing the experiment without having

adequately secured it from any untoward incident or occurrence. In the middle of

the experiment, [Jayson], who was the assistant leader of one of the class groups,

checked the result of the experiment by looking into the test tube with magnifying

glass. At that instance, the compound in the test tube spurted out and several

particles of which hit [Jaysons] eye and the different parts of the bodies of some of

his group mates. [Jaysons] eyes were chemically burned, particularly his left eye,

for which he had to undergo surgery and had to spend for his medication. Upon

filing of this case [in] the lower court, [Jaysons] wound had not completely healed

and still had to undergo another surgery.

• Upon learning of the incident and because of the need for finances,

[Jaysons] mother, who was working abroad, had to rush back home for which she

spent P36,070.00 for her fares and had to forego her salary from November 23,

1994 to December 26, 1994, in the amount of at least P40,000.00.

• Then, too, [Jayson] and his parents also claim for moral damages because of

sleepless nights, mental anguish and wounded feelings, payment of his medical

expenses and litigation expenses, including attorneys fees.

•](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-201-320.jpg)

![Petitioners SJC, Sr. Josephini Ambatali, SFIC, and Tabugo] alleged

that strict instructions to follow the written procedure for the experiment and

not to look into the test tube until the heated compound had cooled off was

done. That it was the discretion [Jayson] to look at the test tube.

The school treat Jayson to the school clinic and transferred to St.

Lukes Medical Center for treatment. At the hospital, when Tabago visited

[Jayson], the latter cried and apologized to his teacher for violating her

instructions.

After the treatment, [Jayson] was pronounced ready for discharge

and an eye test showed that his vision had not been impaired or affected. In

order to avoid additional hospital charges due to the delay in [Jaysons]

discharge, Rodolfo S. Miranda, [Jaysons] father, requested SJC to advance

the amount of P26,176.35 representing [Jaysons] hospital bill until his wife

could arrive from abroad and pay back the money. SJC acceded to the

request.

However, the parents of [Jayson], through counsel, wrote SJC a letter

demanding that it should shoulder all the medical expenses of caused by the

science experiment.

Sr. Josephini Ambatali, SFIC, explained that the school cannot

accede to the demand because the accident occurred by reason of [Jaysons]

failure to comply with the written procedure and his teachers repeated

warnings and instruction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-202-320.jpg)

![WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered

in favor of [Jayson] and against [petitioners]. This Court orders and holds

the [petitioners] joint[ly] and solidarily liable to pay [Jayson] the following

amount:

1. To pay [Jayson] the amount of P77,338.25 as actual damages; However,

[Jayson] is ordered to reimburse [petitioner] St. Joseph College the amount

of P26,176.36 representing the advances given to pay [Jaysons] initial

hospital expenses or in the alternative to deduct said amount of P26,176.36

from the P77,338.25 actual damages herein awarded by way of legal

compensation;

2. To pay [Jayson] the sum of P50,000.00 as mitigated moral damages;

3. To pay [Jayson] the sum of P30,000.00 as reasonable attorneys fees;

4. To pay the costs of suit.

Aggrieved, petitioners appealed to the CA. However, as previously

adverted to, the CA affirmed in toto the ruling of the RTC, thus:

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the assailed decision of

the RTC of Quezon City, Branch 221 dated September 6, 2000 is

hereby AFFIRMED IN TOTO.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/multiplechoiceitemtest-230414035454-71b5a94d/85/Multiple-Choice-Item-Test-pptx-203-320.jpg)