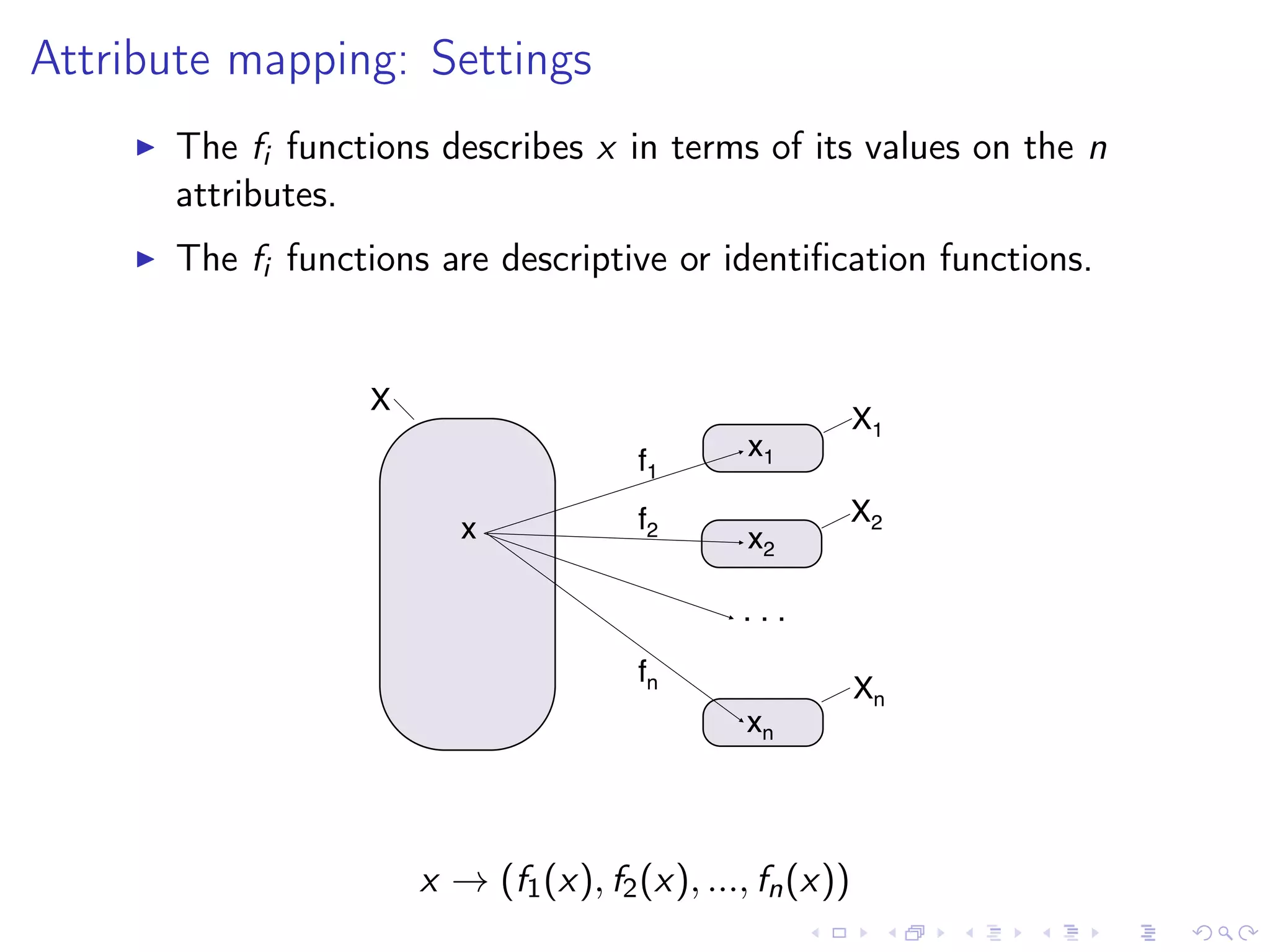

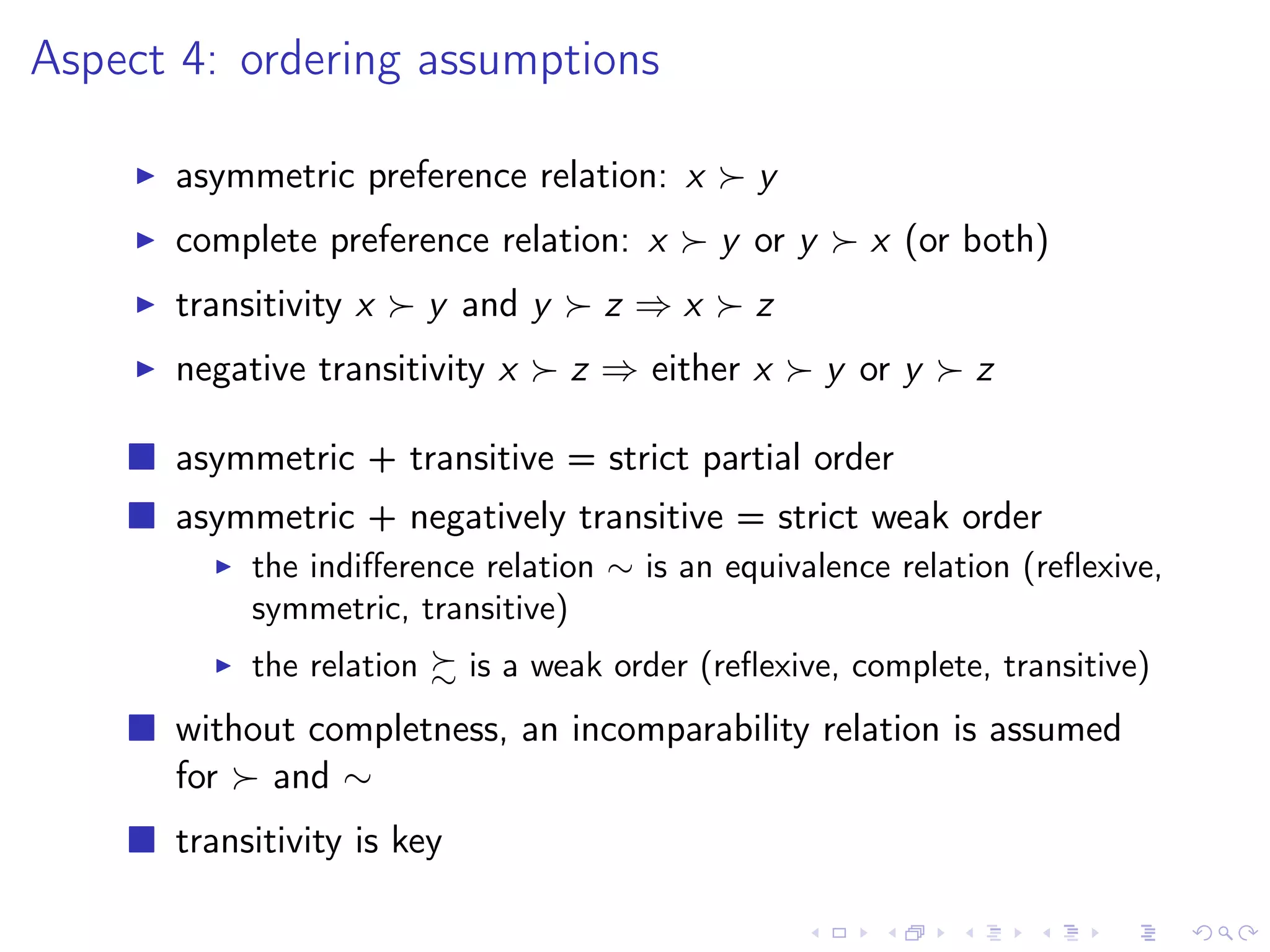

This document provides an introduction to multiattribute decision making and decision theories. It discusses several key aspects of multiattribute choice models, including:

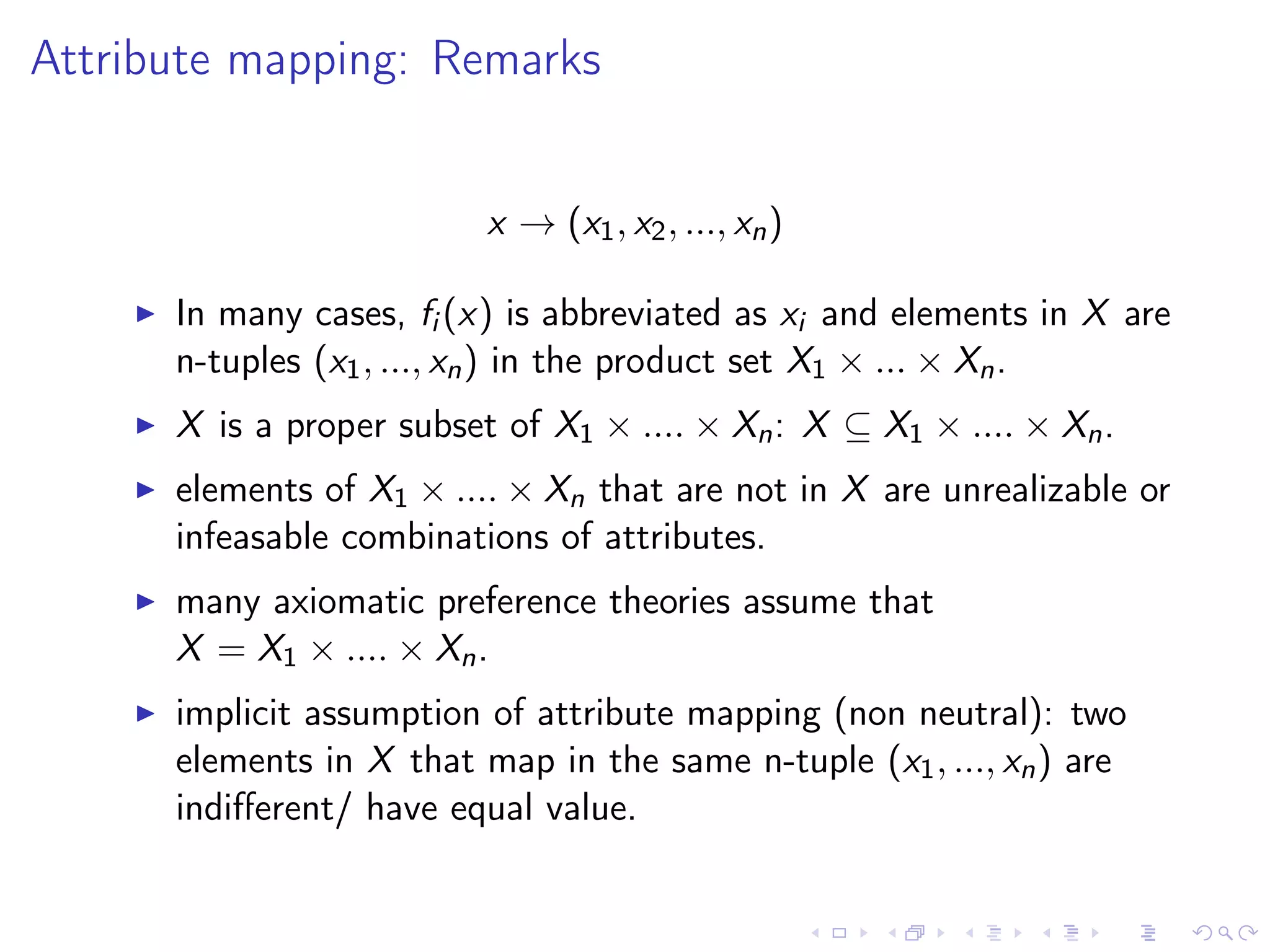

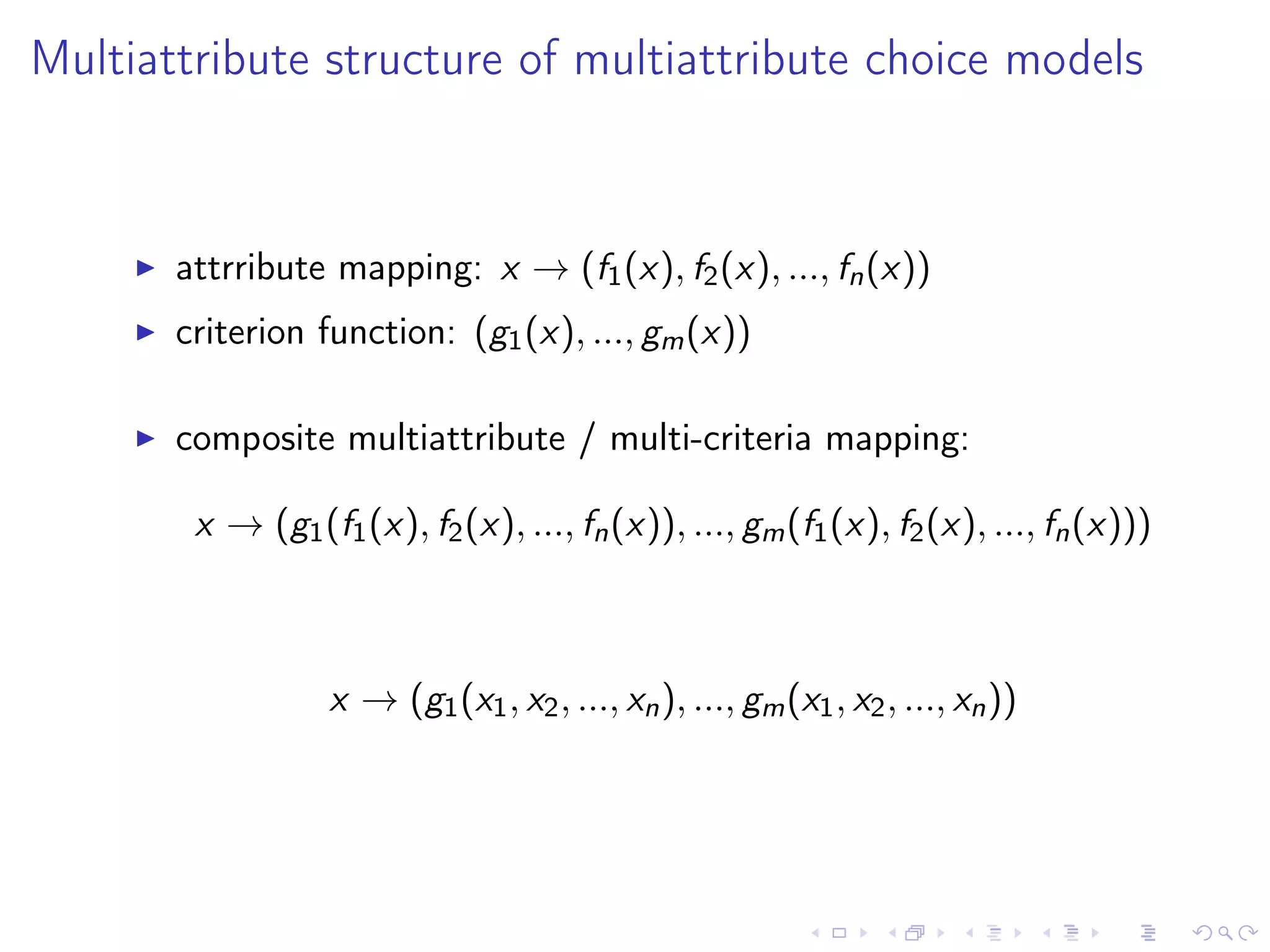

1) The number and nature of attributes that are used to differentiate decision alternatives.

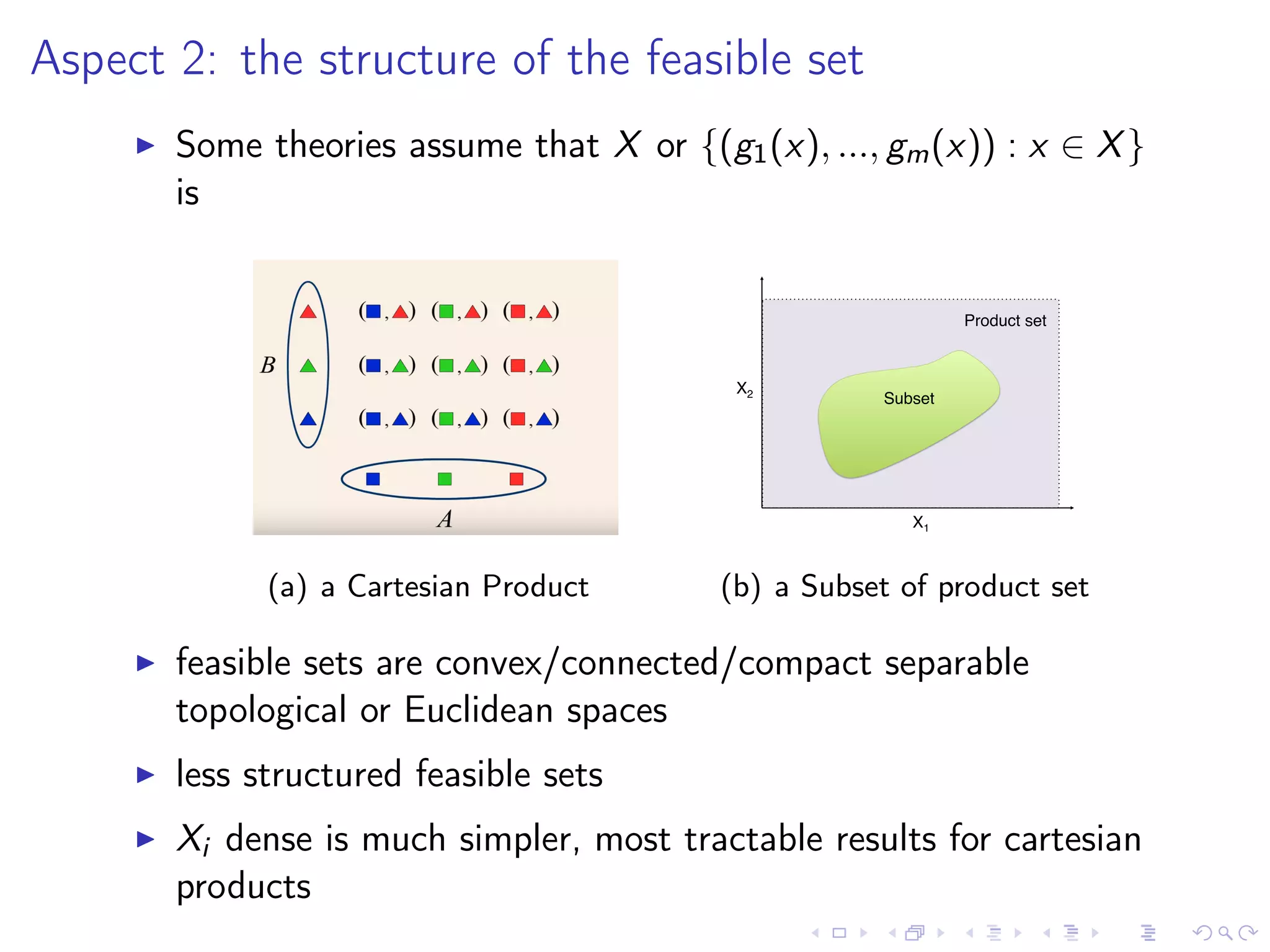

2) The structure of the feasible set of alternatives.

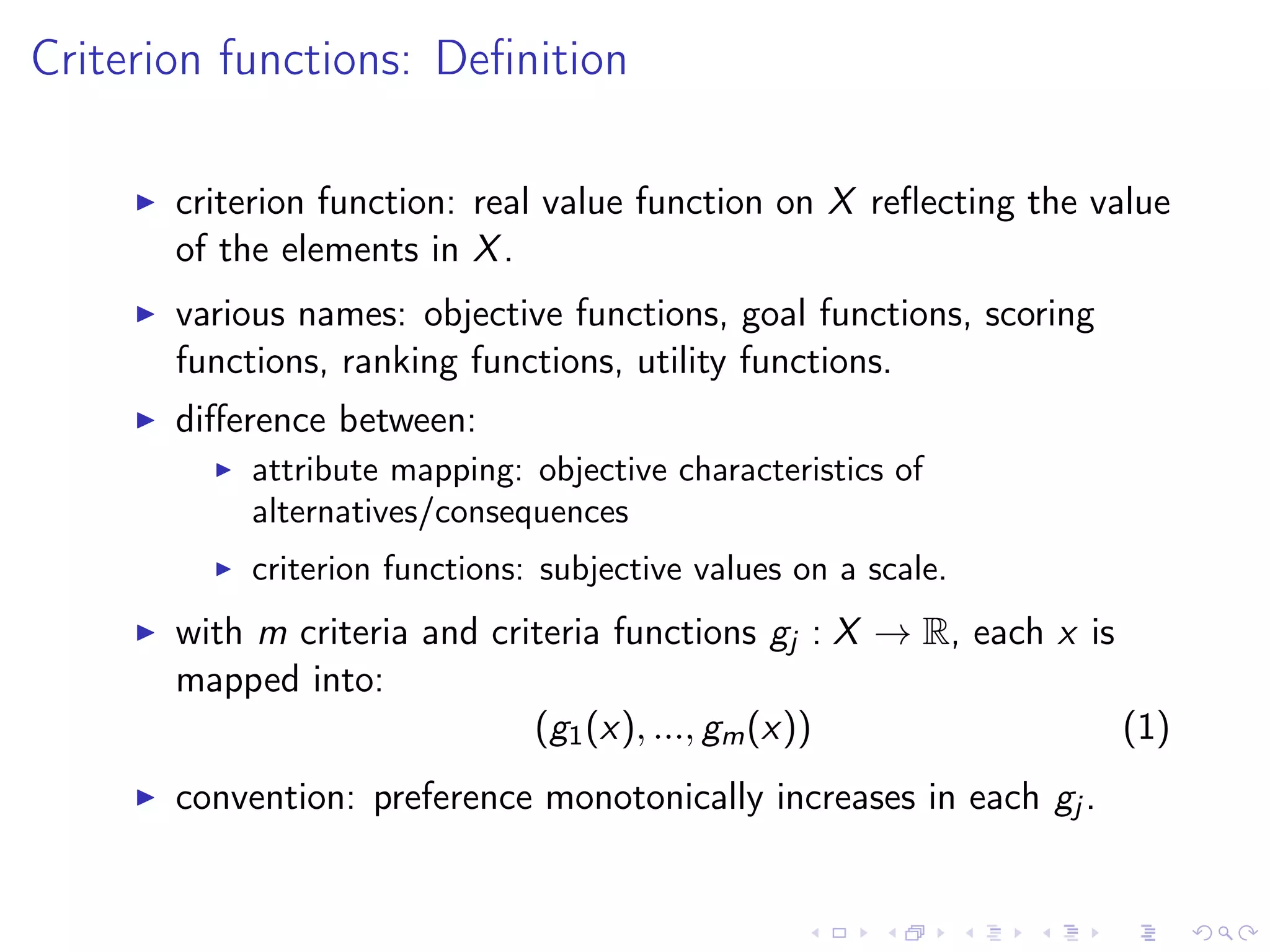

3) The basis of evaluation, such as preference relations or criterion functions.

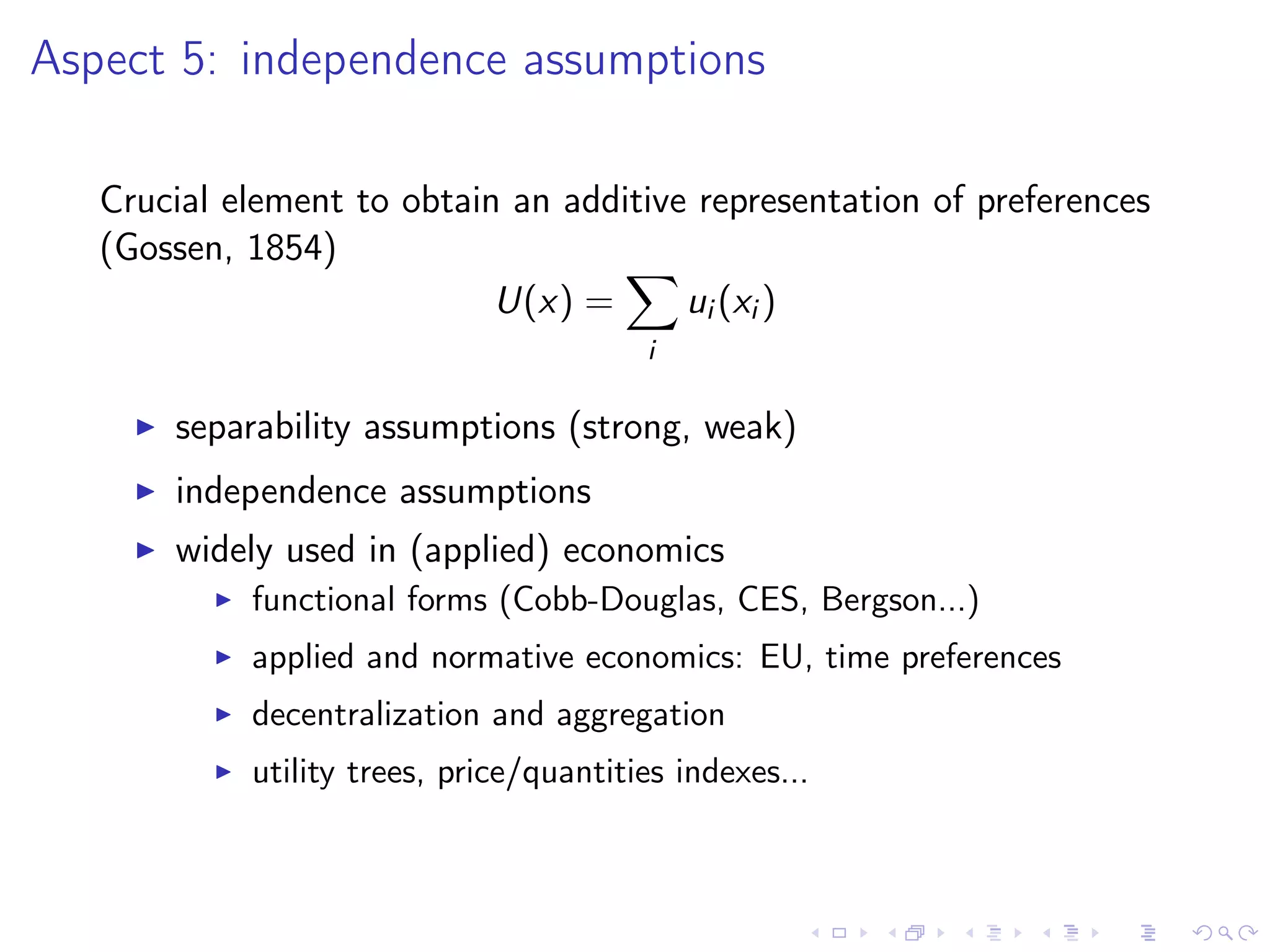

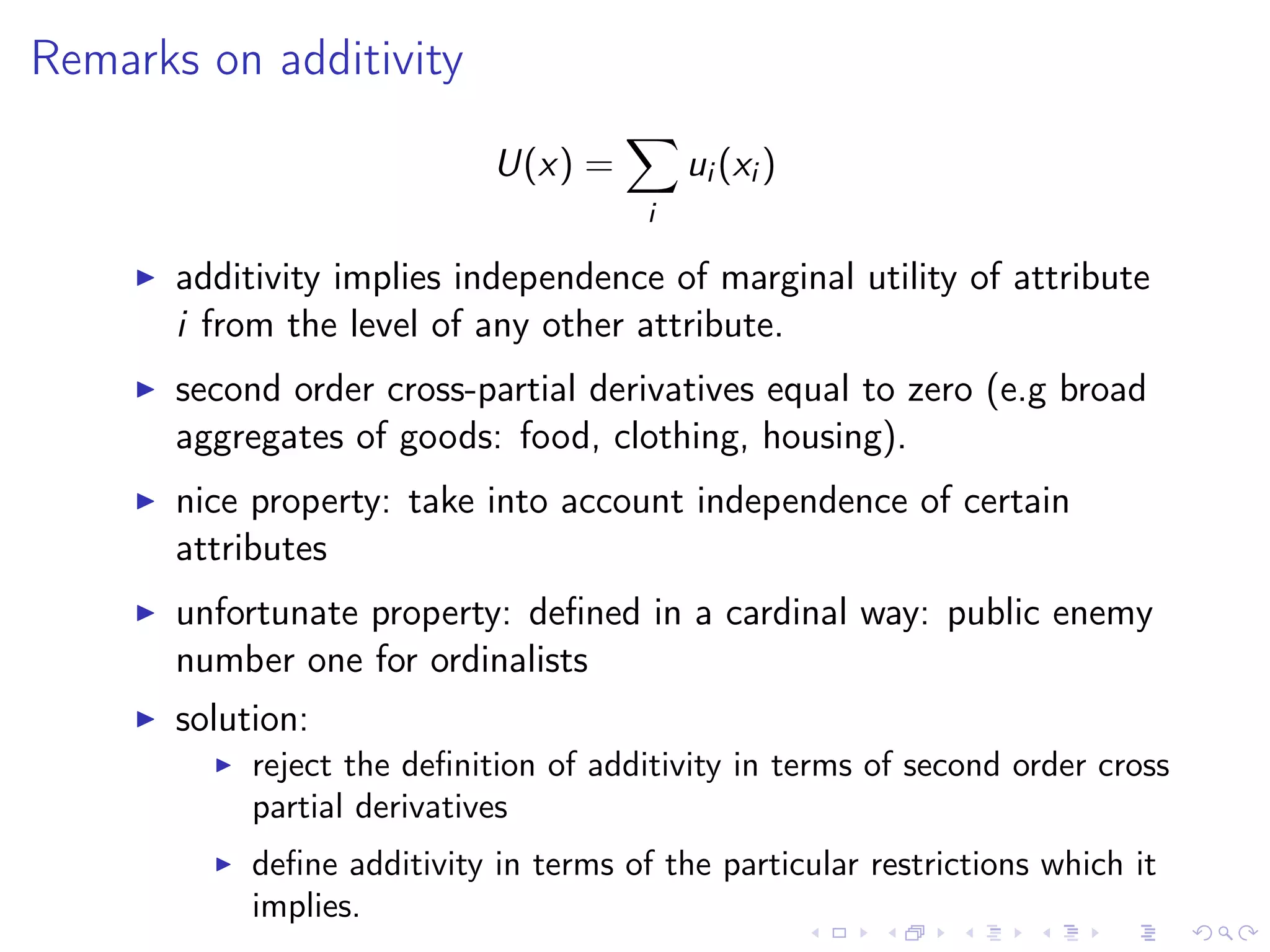

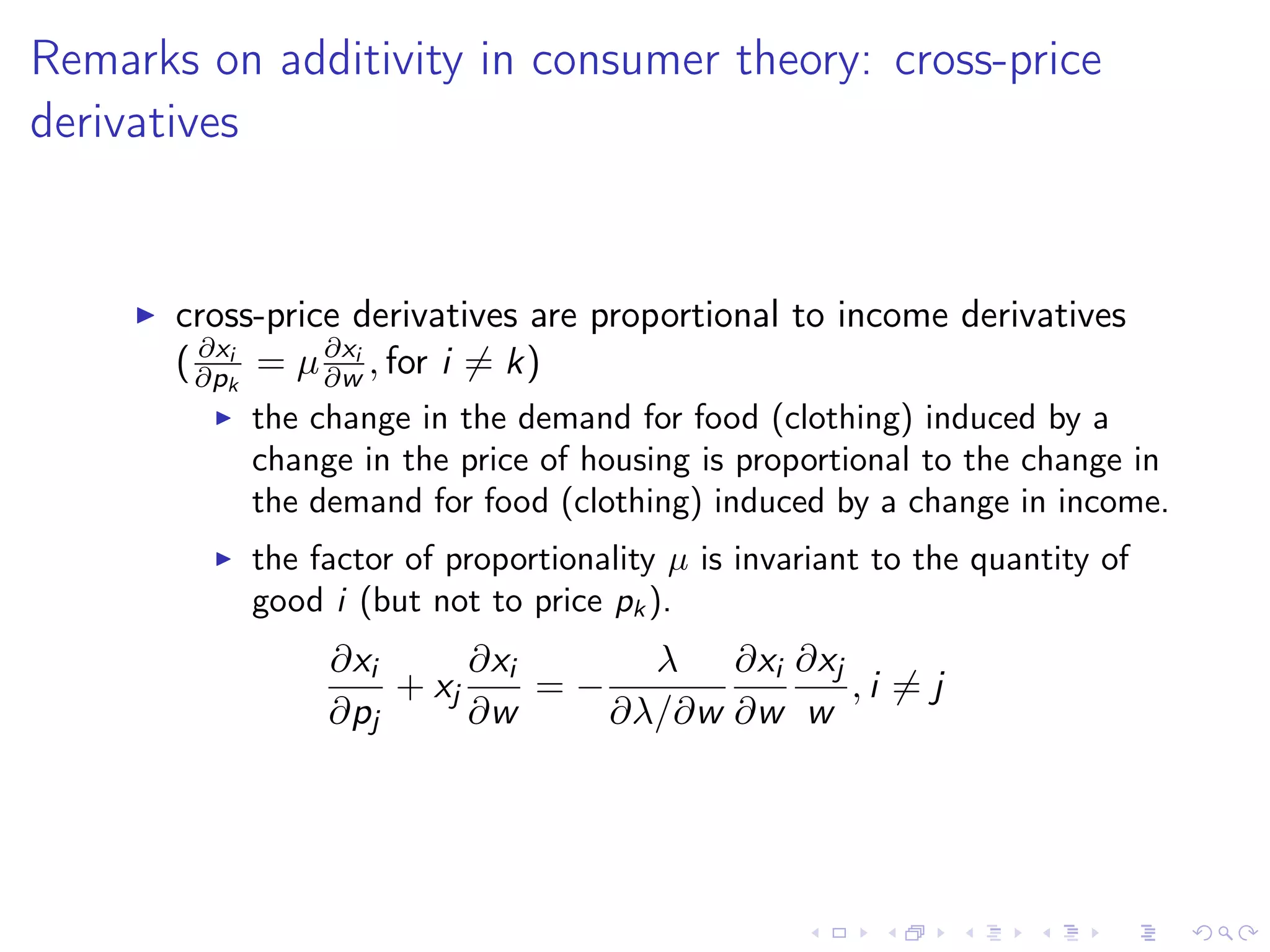

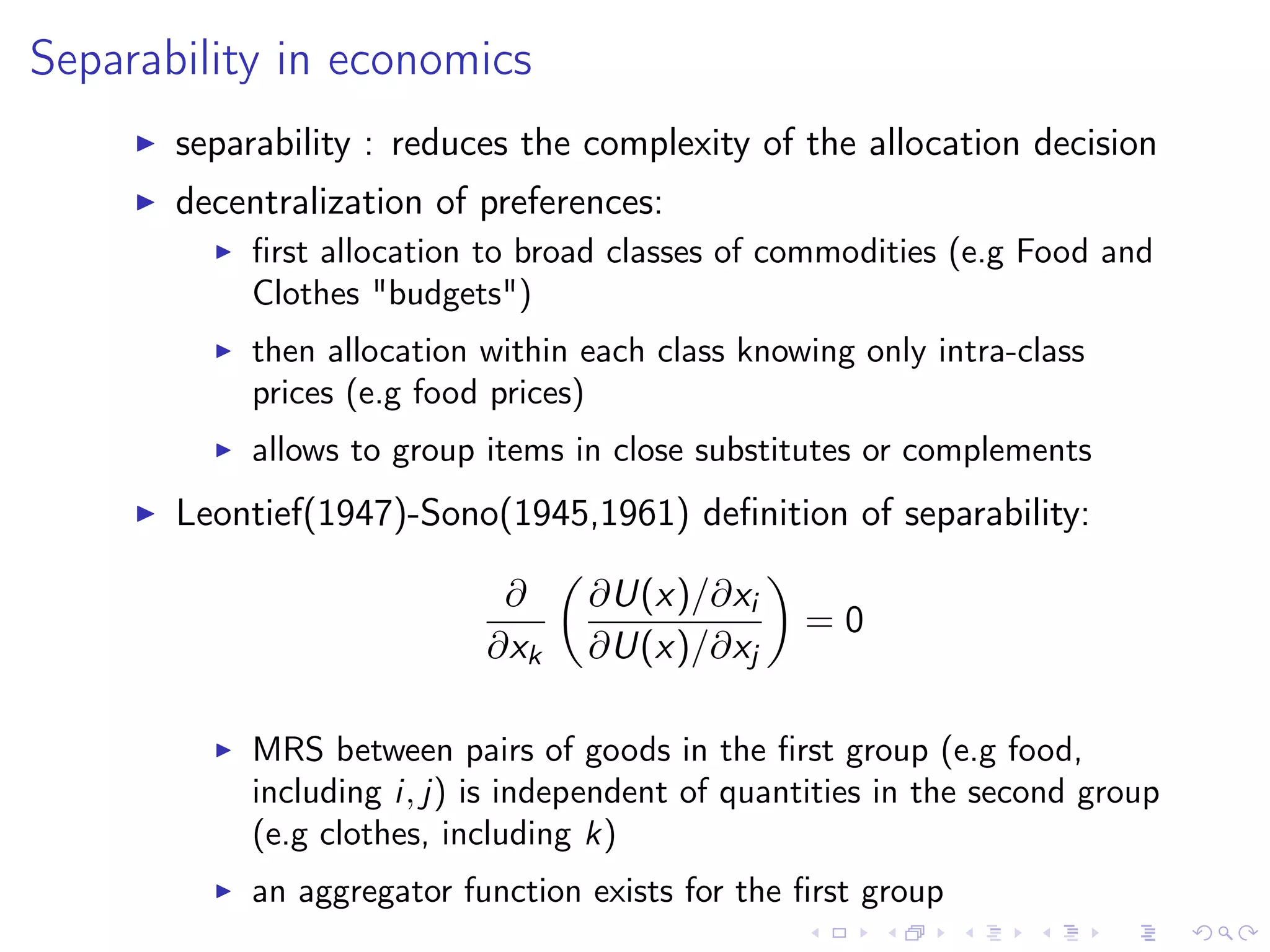

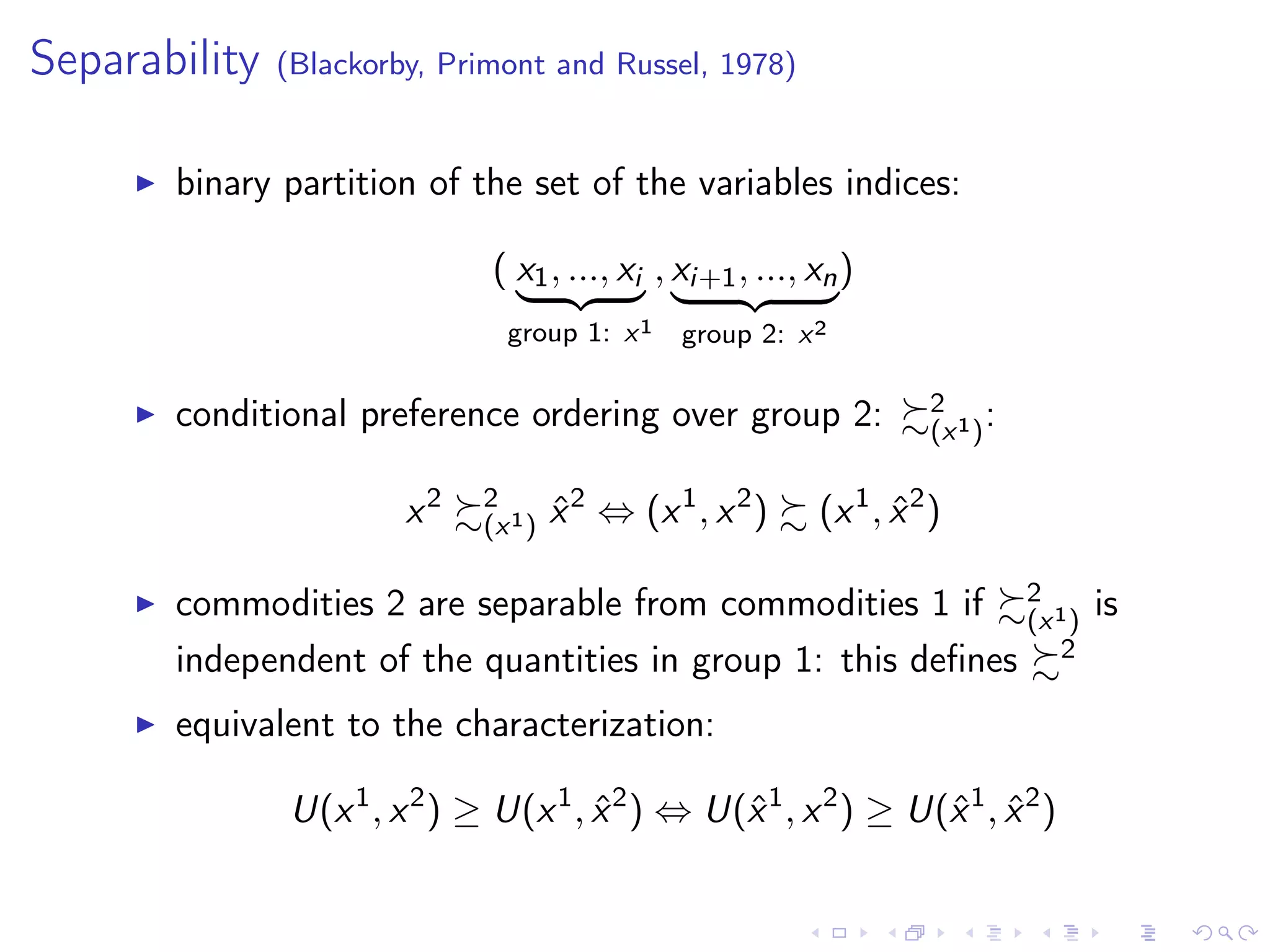

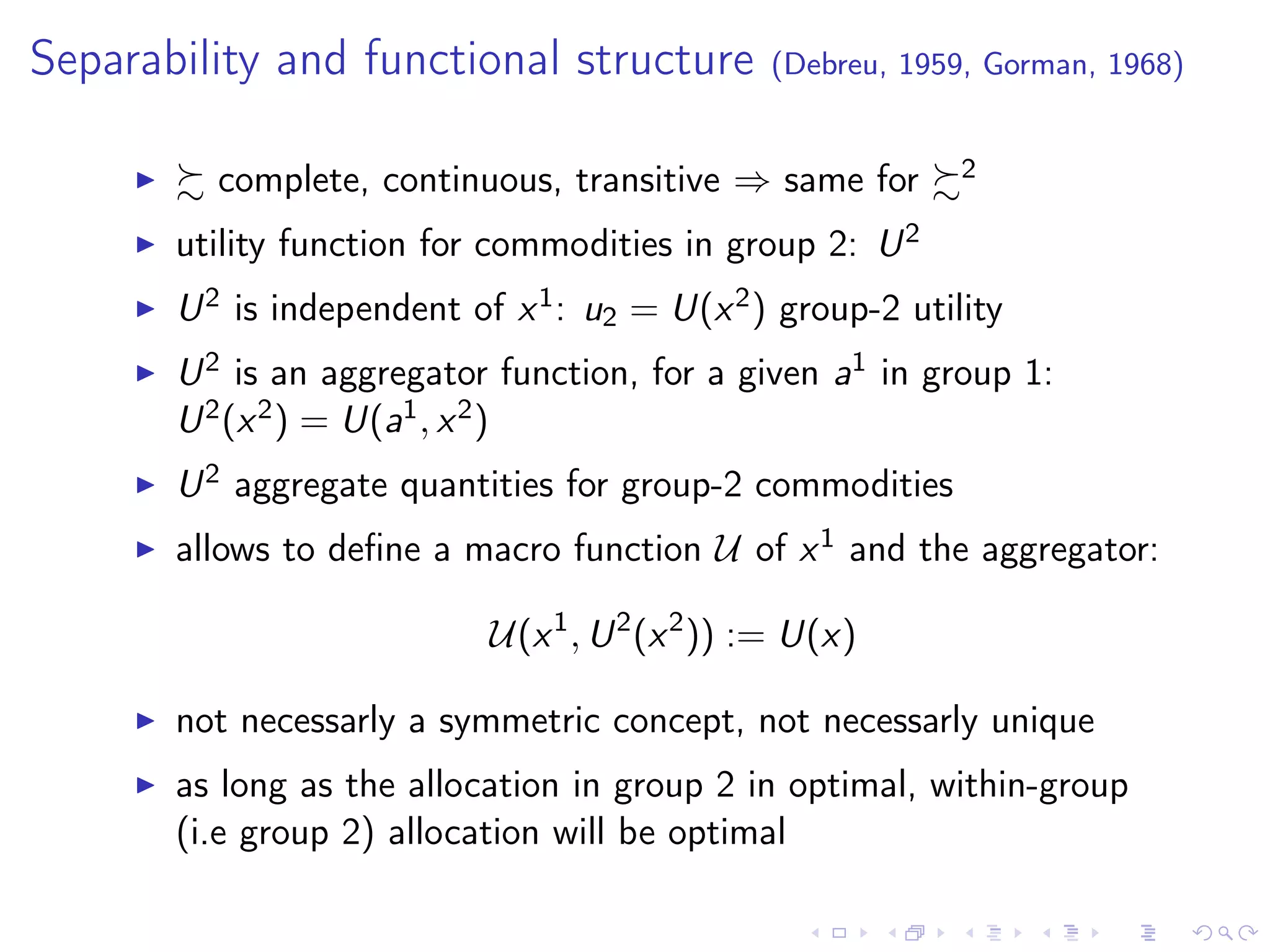

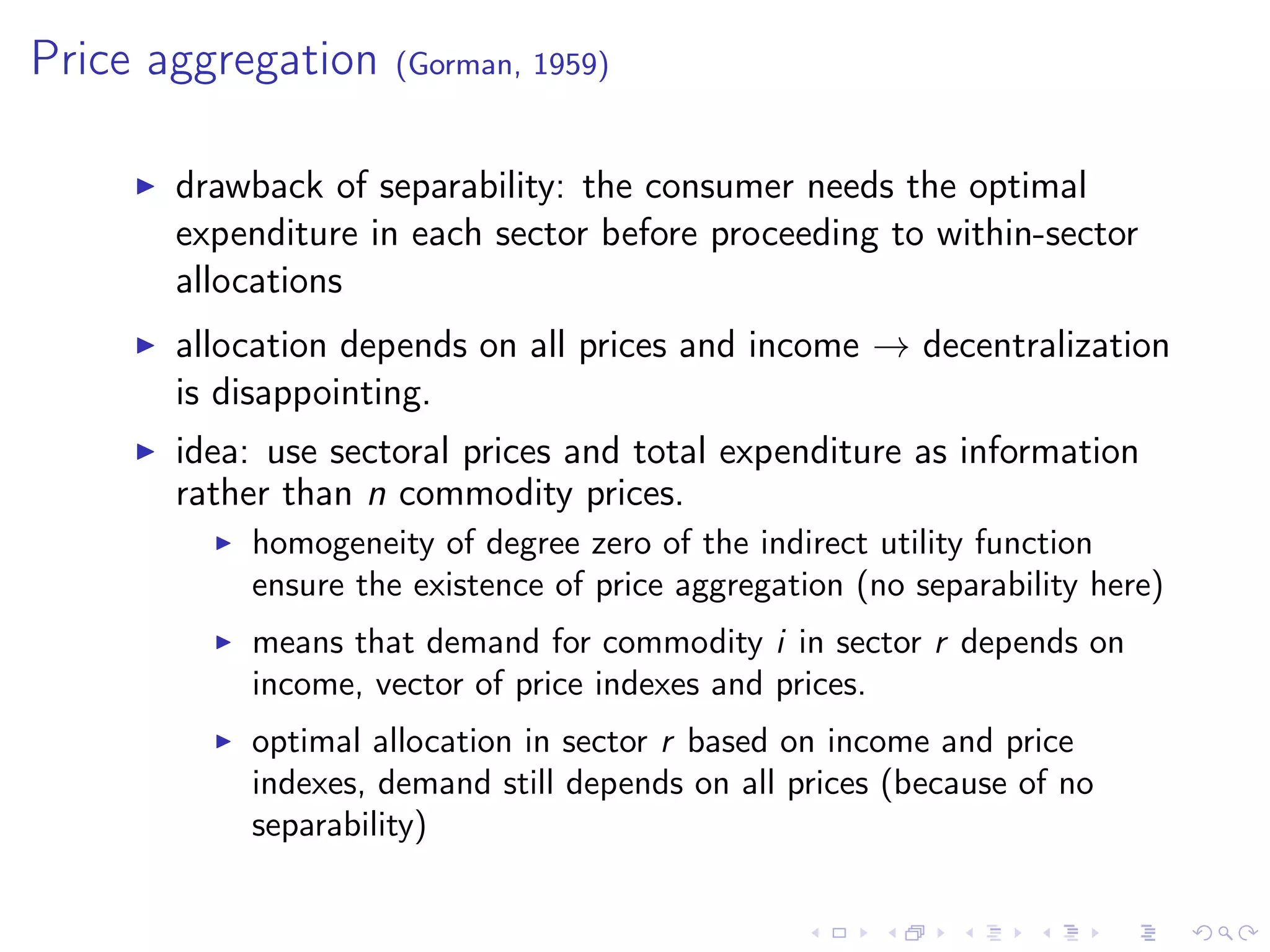

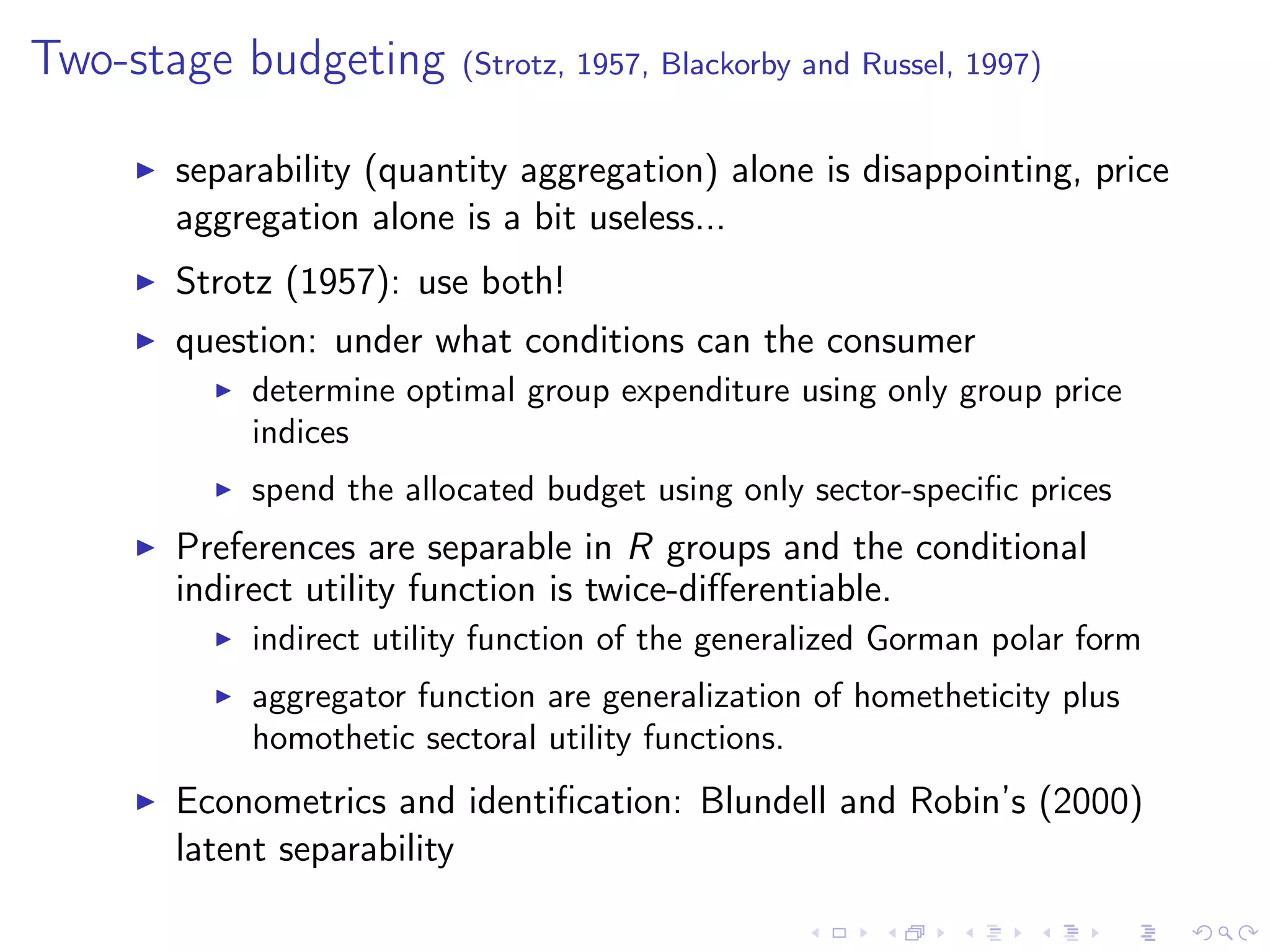

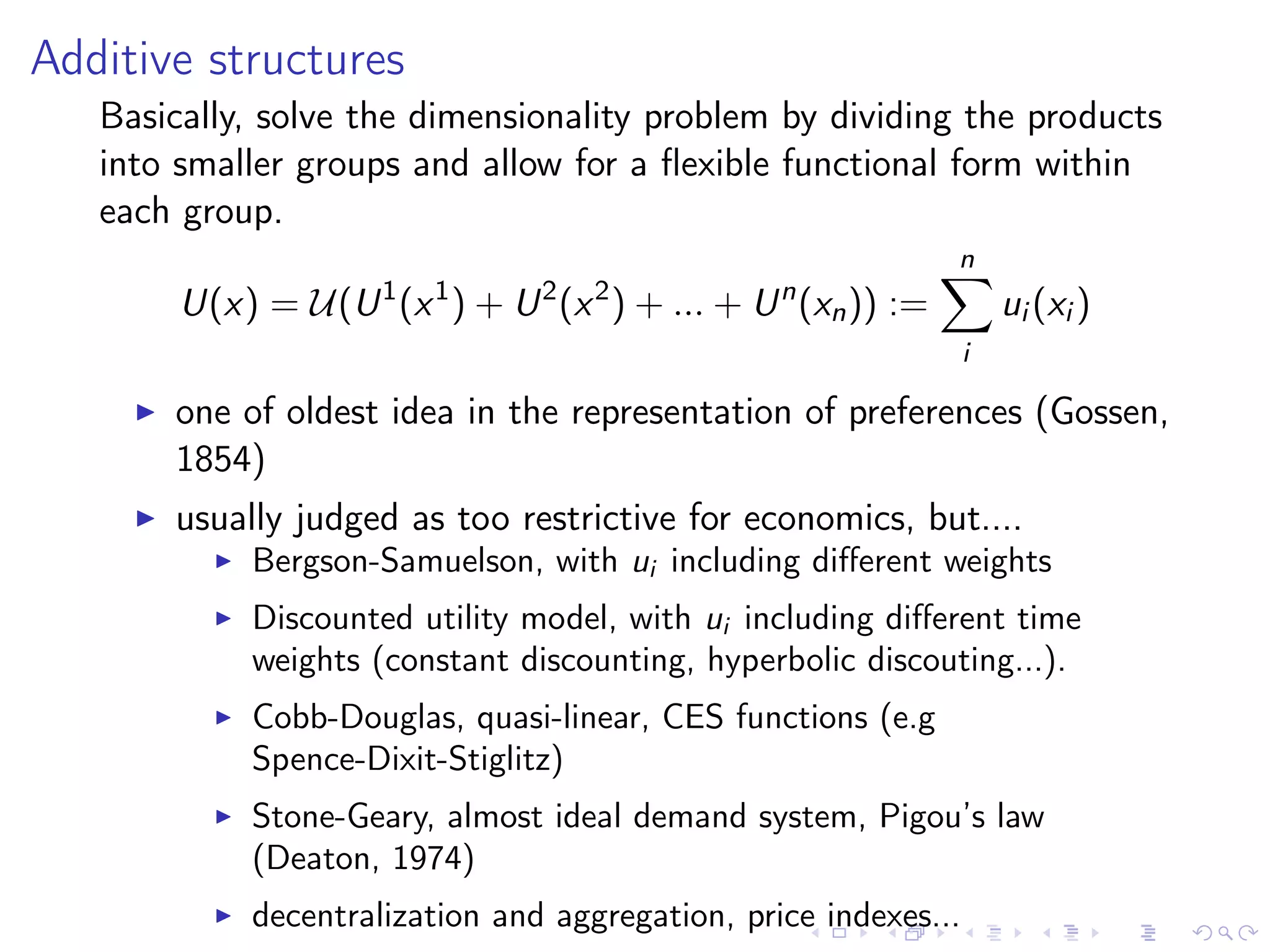

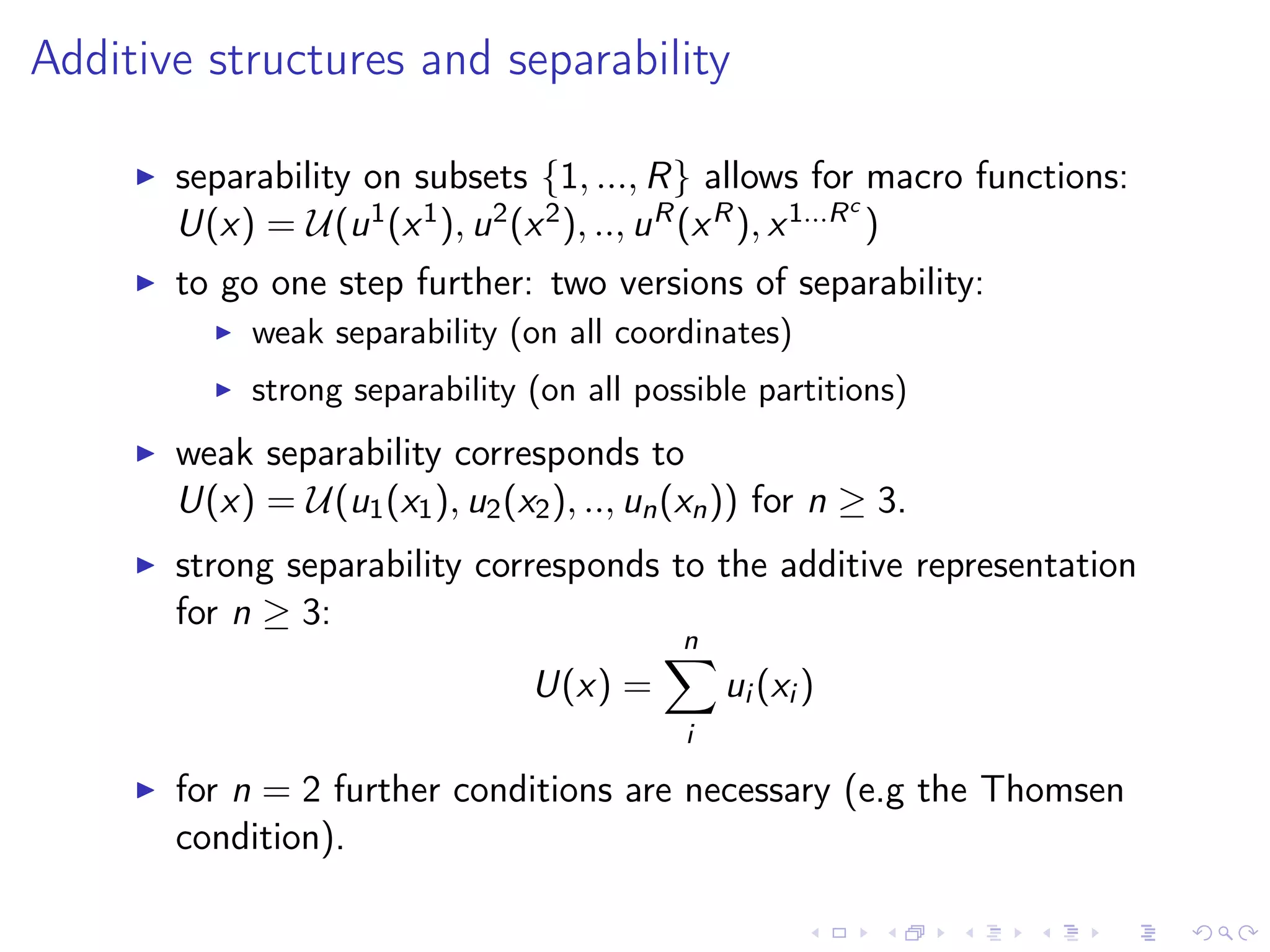

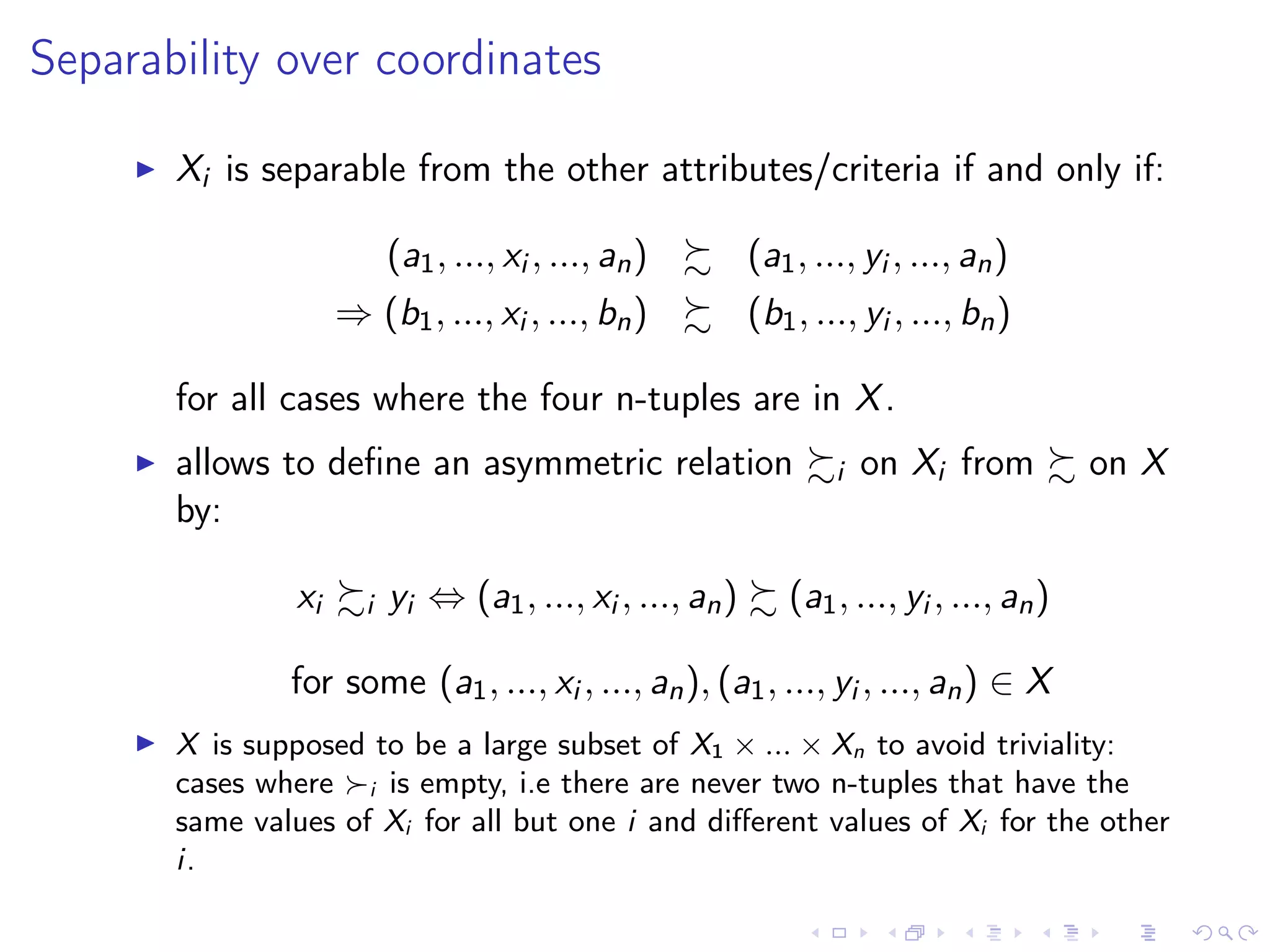

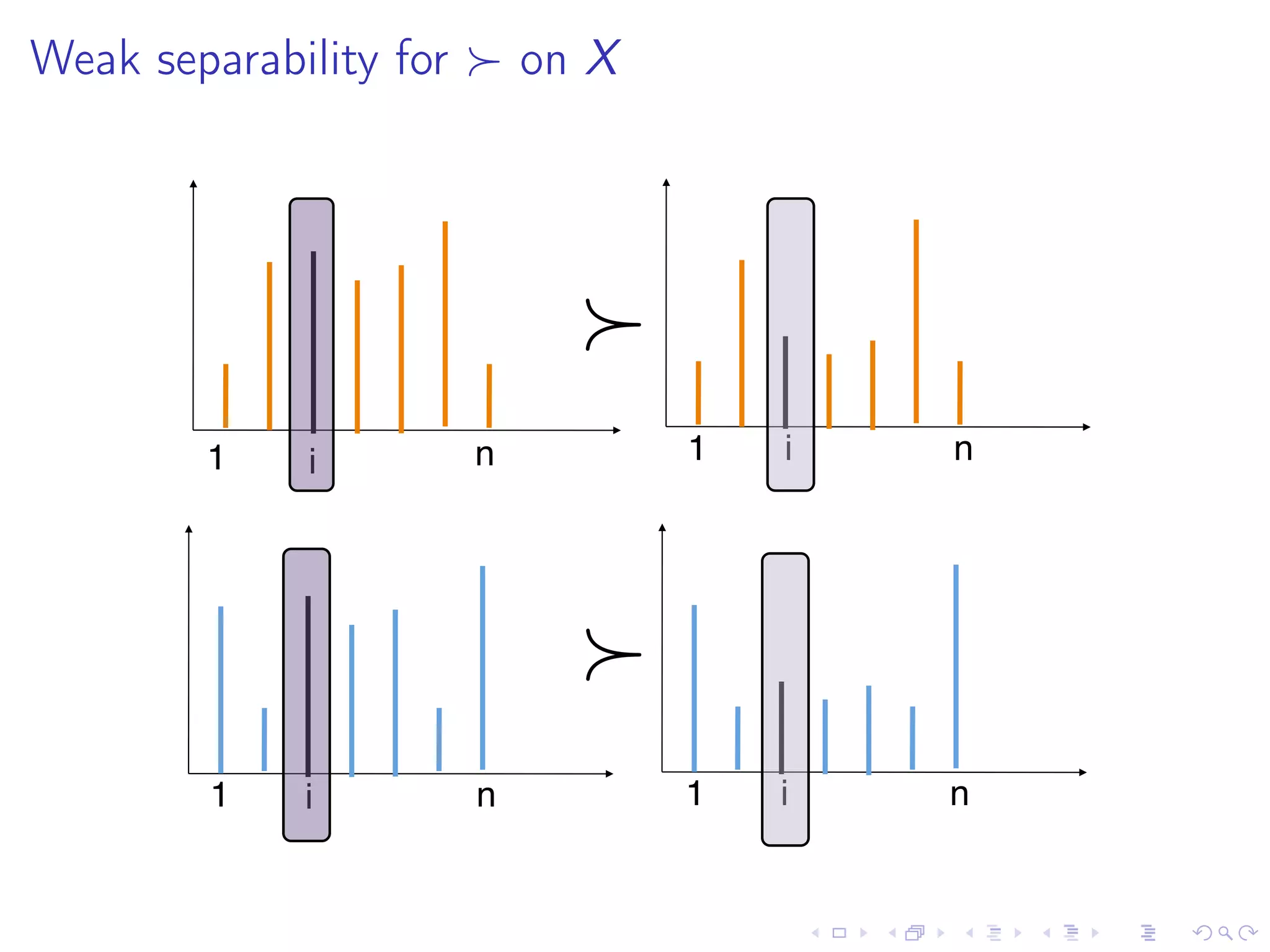

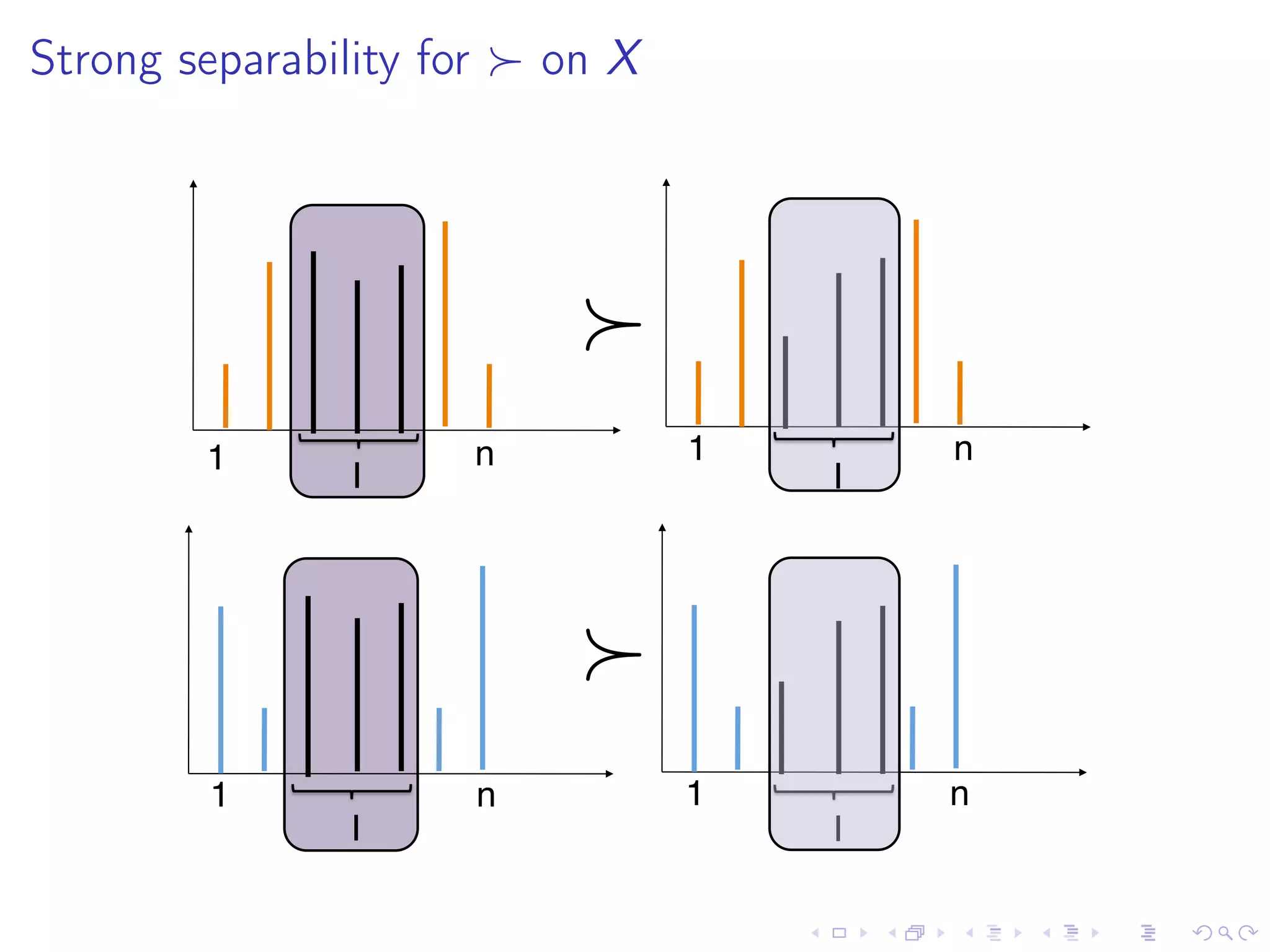

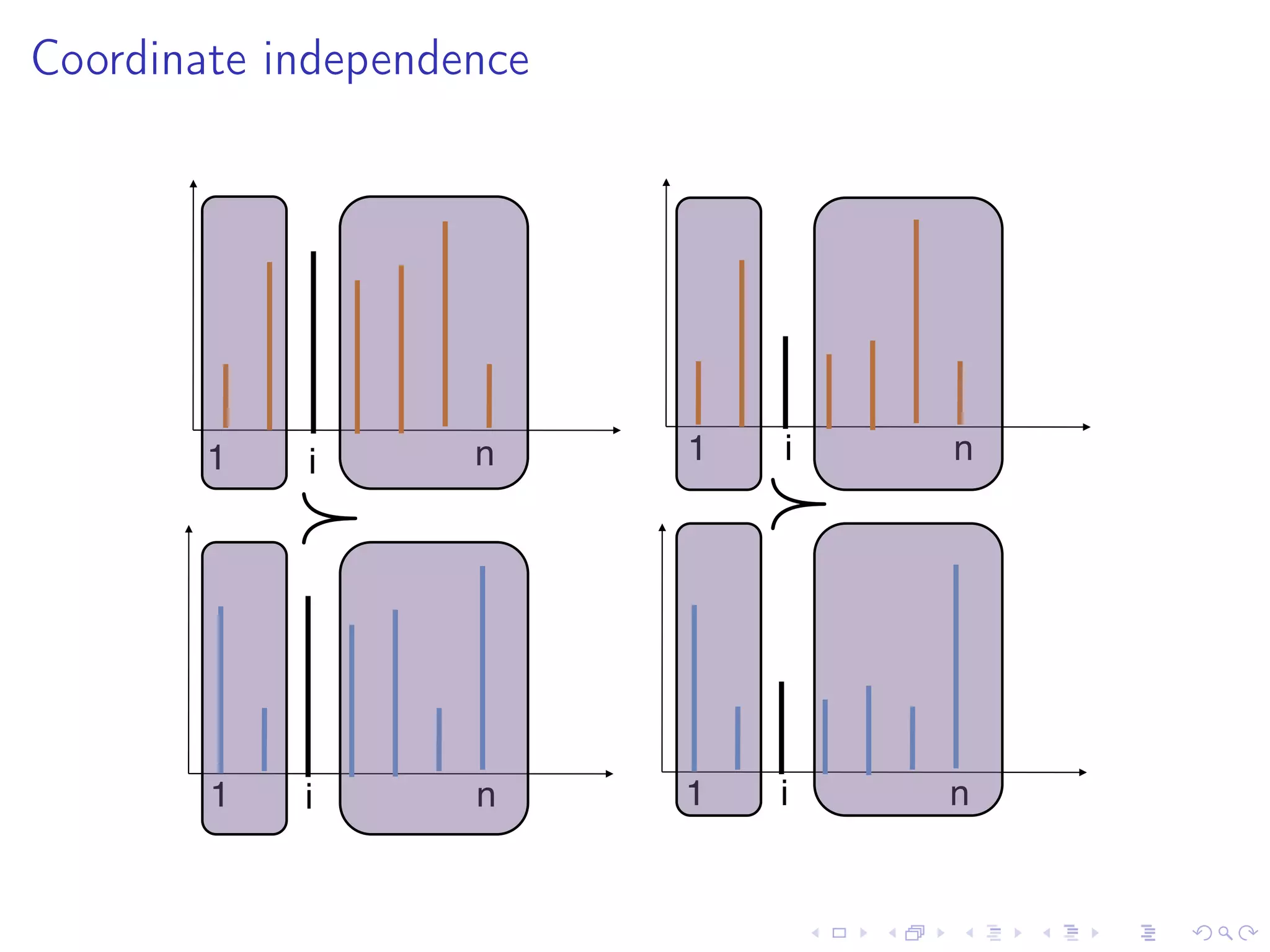

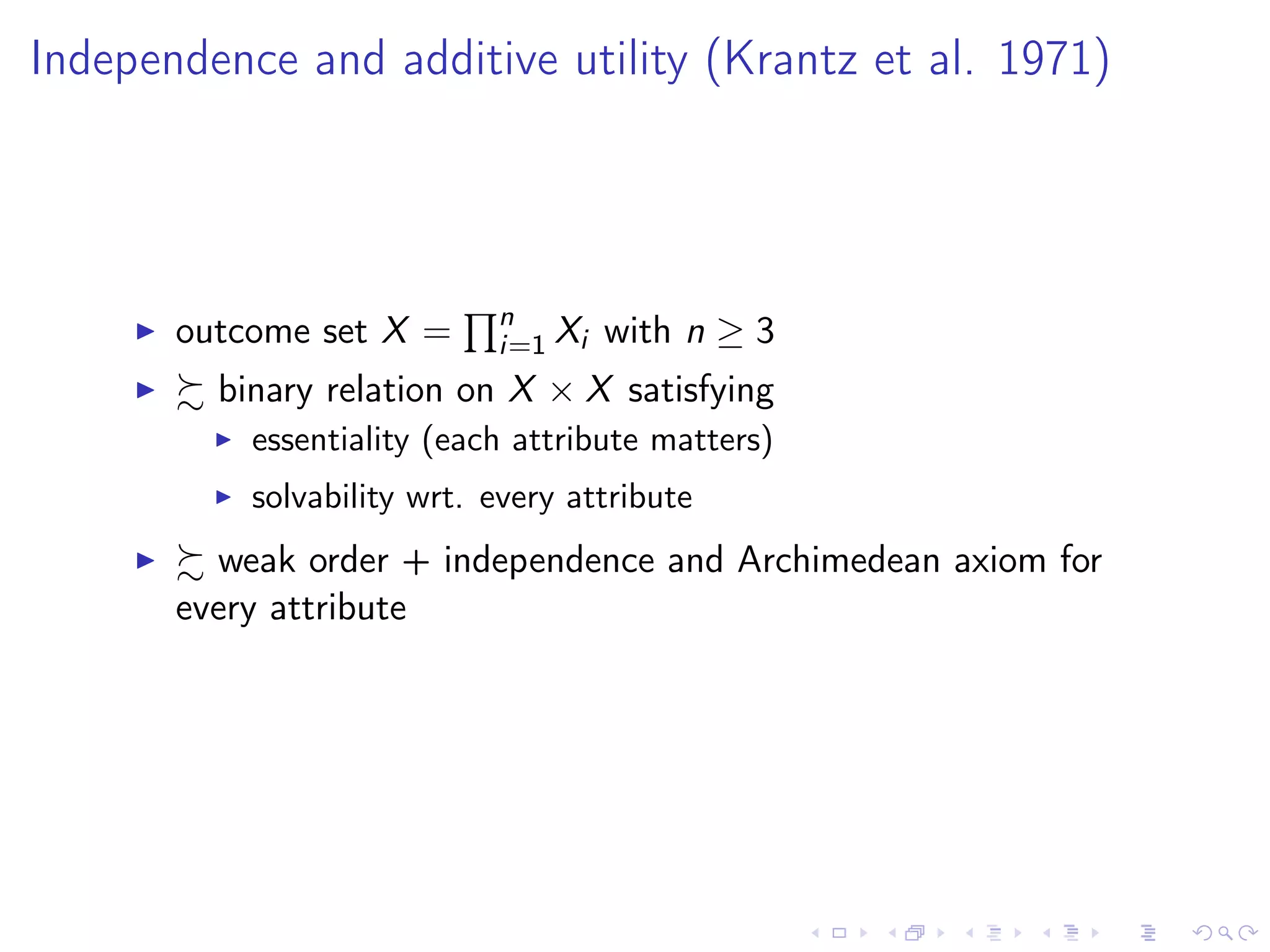

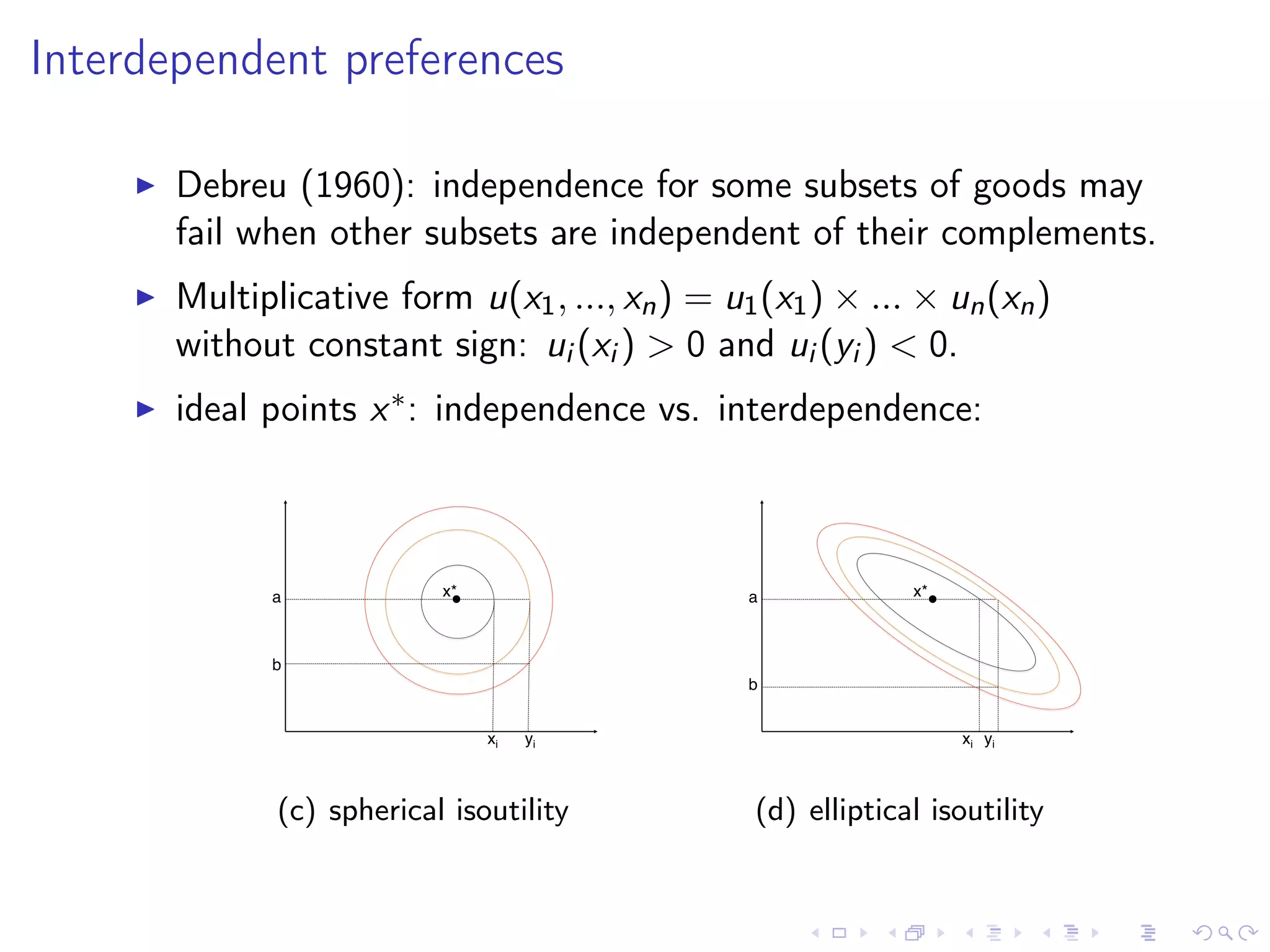

4) Independence and separability assumptions that are required to obtain additive representations of preferences.

The document outlines some classic evaluation theories under certainty that do not involve probabilities, and discusses the concept of separability, which reduces complexity by allowing decentralized preferences across attribute groups.