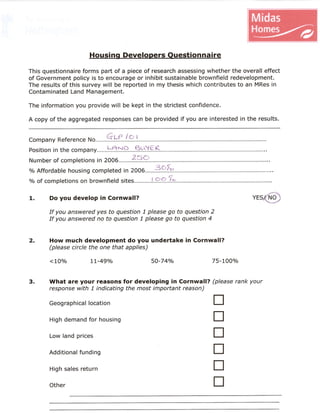

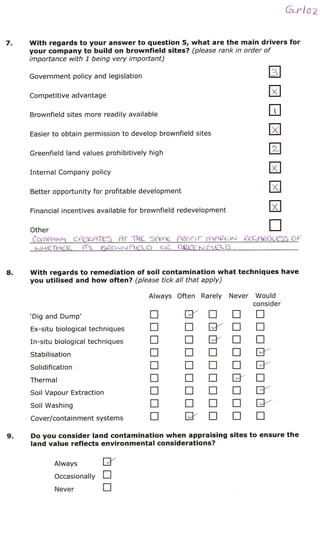

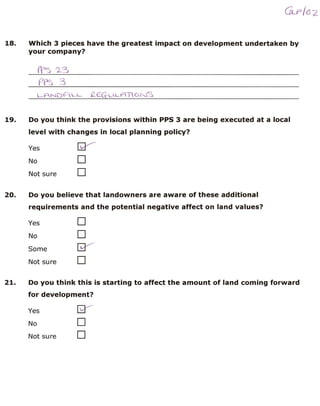

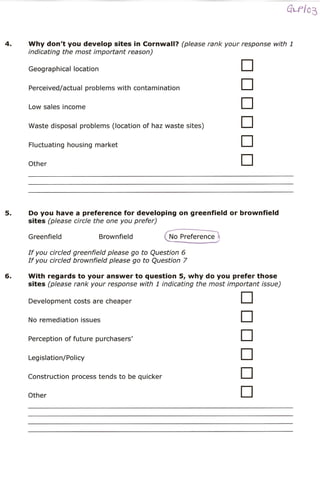

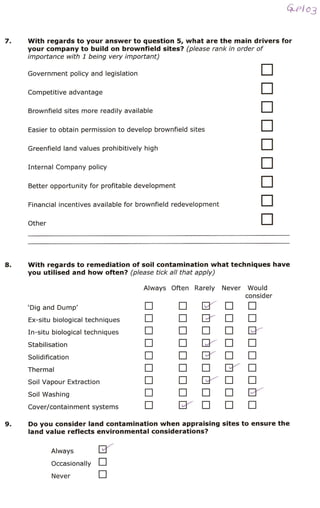

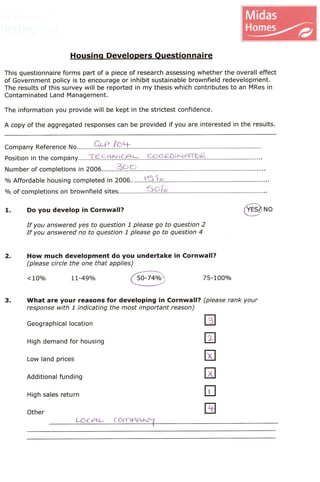

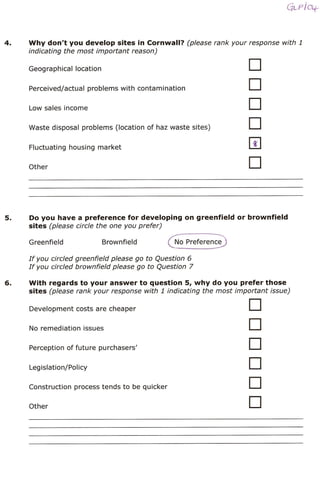

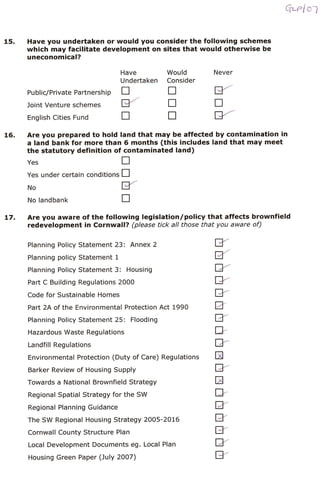

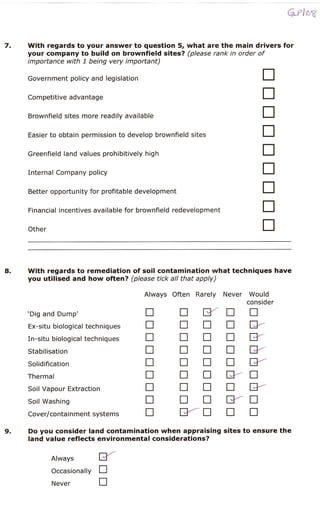

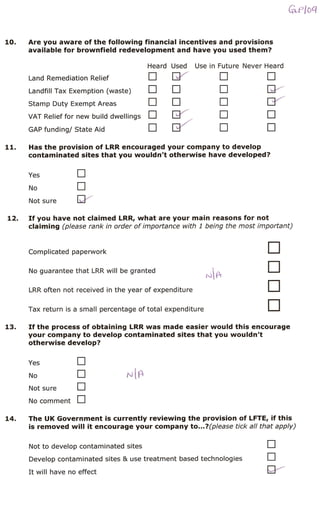

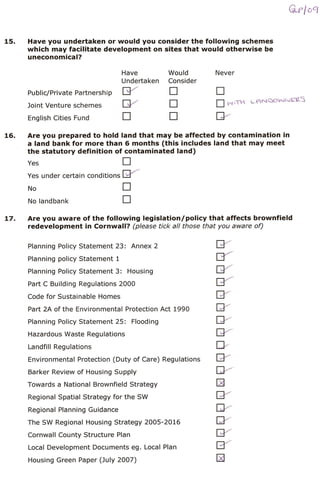

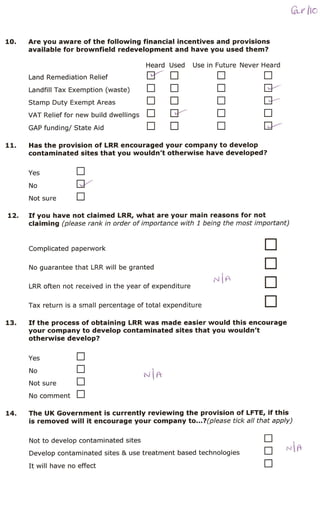

This dissertation evaluates whether government policy in the UK encourages sustainable brownfield redevelopment. It assesses legislation, financial incentives and surveys developers in southwest England. The literature review found that policy aims to promote brownfield use through laws and funding, however incentives are underused and sustainability is lacking emphasis. Survey results suggest developers regularly redevelop brownfields in Cornwall without major barriers. Respondents indicated national policy around housing is impacting land values locally. While sample size was limited, results demonstrate policy encourages brownfield reuse but could better promote sustainability through clear criteria for funding allocation.