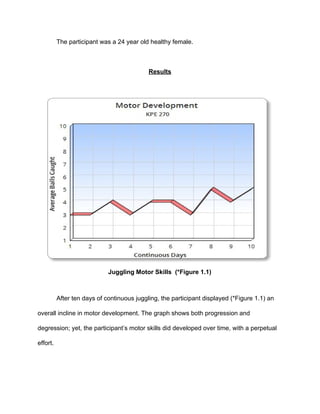

This document discusses motor skill development over a 10-day period where a participant practiced juggling tennis balls. It describes the three stages of motor learning identified by Fitts and Posner as cognitive, affective, and autonomous. The participant recorded their juggling performance daily, showing progression and regression. On some days, the participant introduced variables like environment, goals, and music to measure their effects on development. Overall, the experiment demonstrated the importance of the three learning stages and repetitive practice for gaining motor control of a new skill.