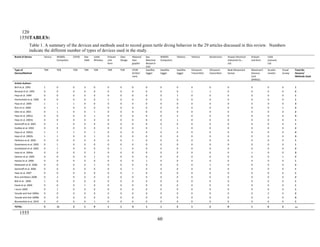

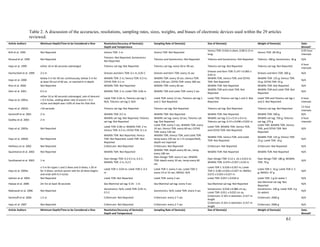

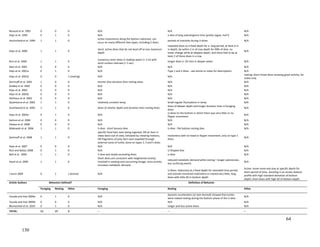

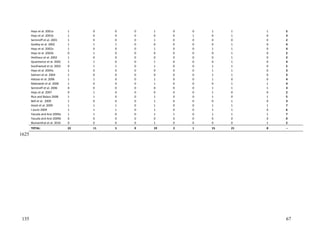

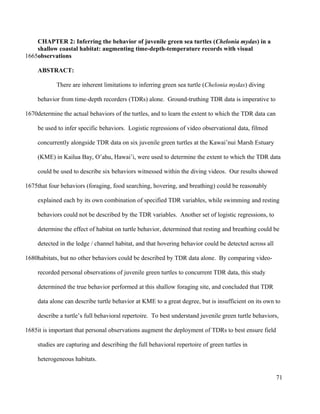

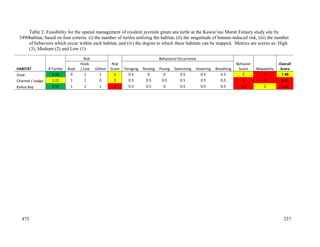

This document provides a literature review of 29 articles that studied green sea turtle diving behavior using electronic devices. It discusses the history of sea turtle behavior studies, comparing the use of satellite loggers and time-depth recorders to collect dive data. The definitions of behaviors like foraging and resting are examined. Additional factors discussed include study locations, sample sizes, and ecological influences on dive behavior. The review considers how these various methodological factors must be accounted for when analyzing dive behavior studies.