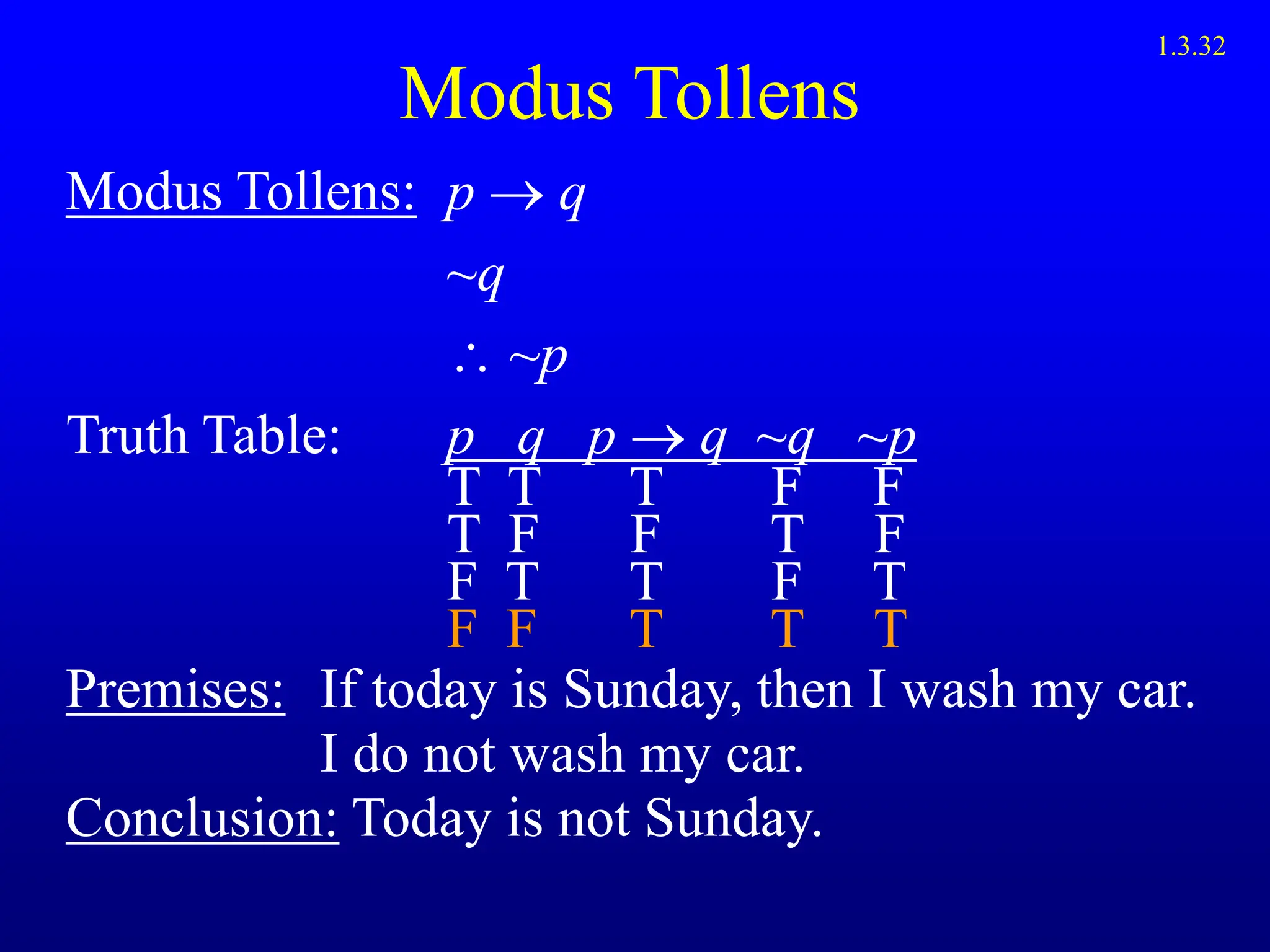

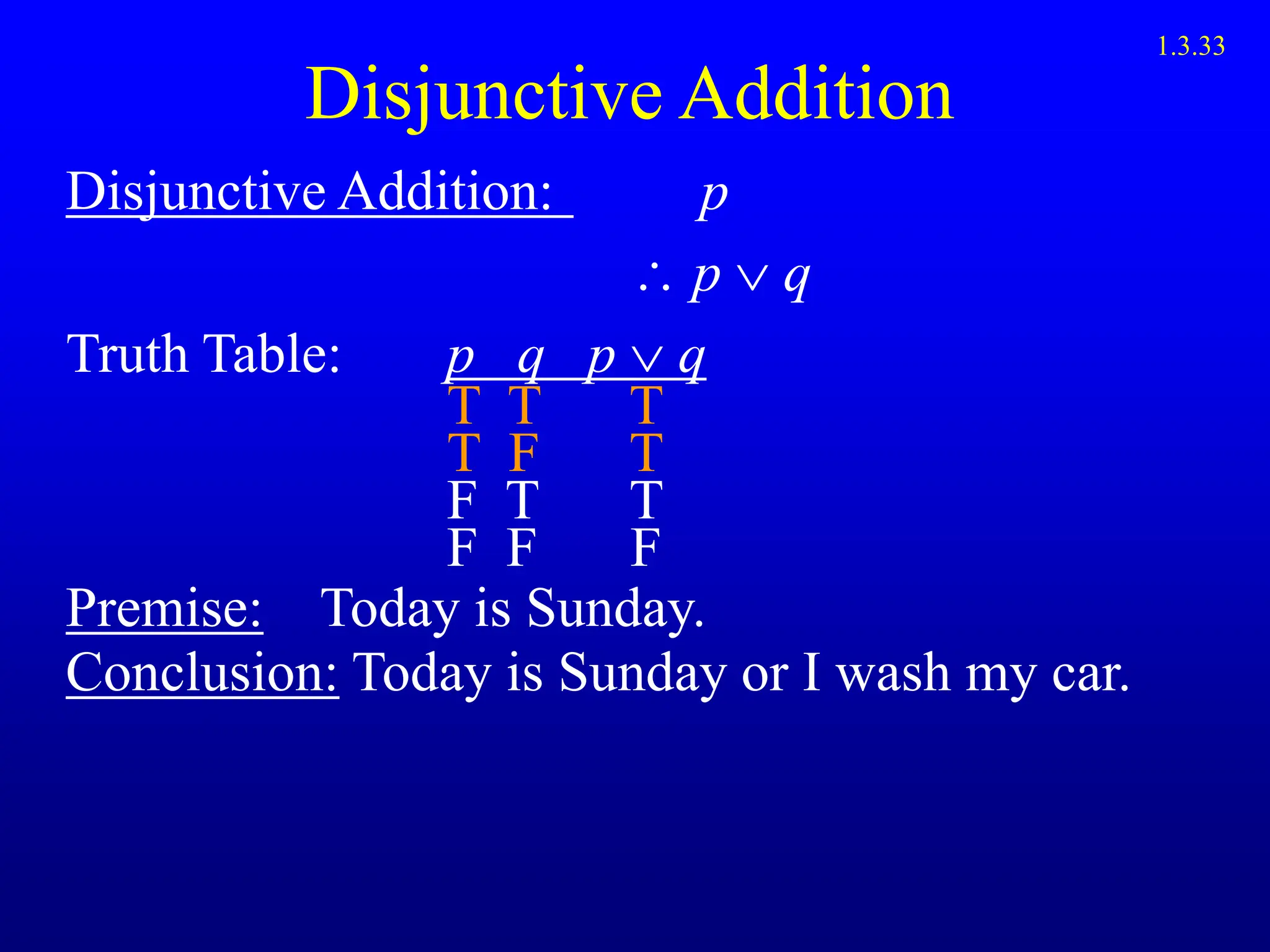

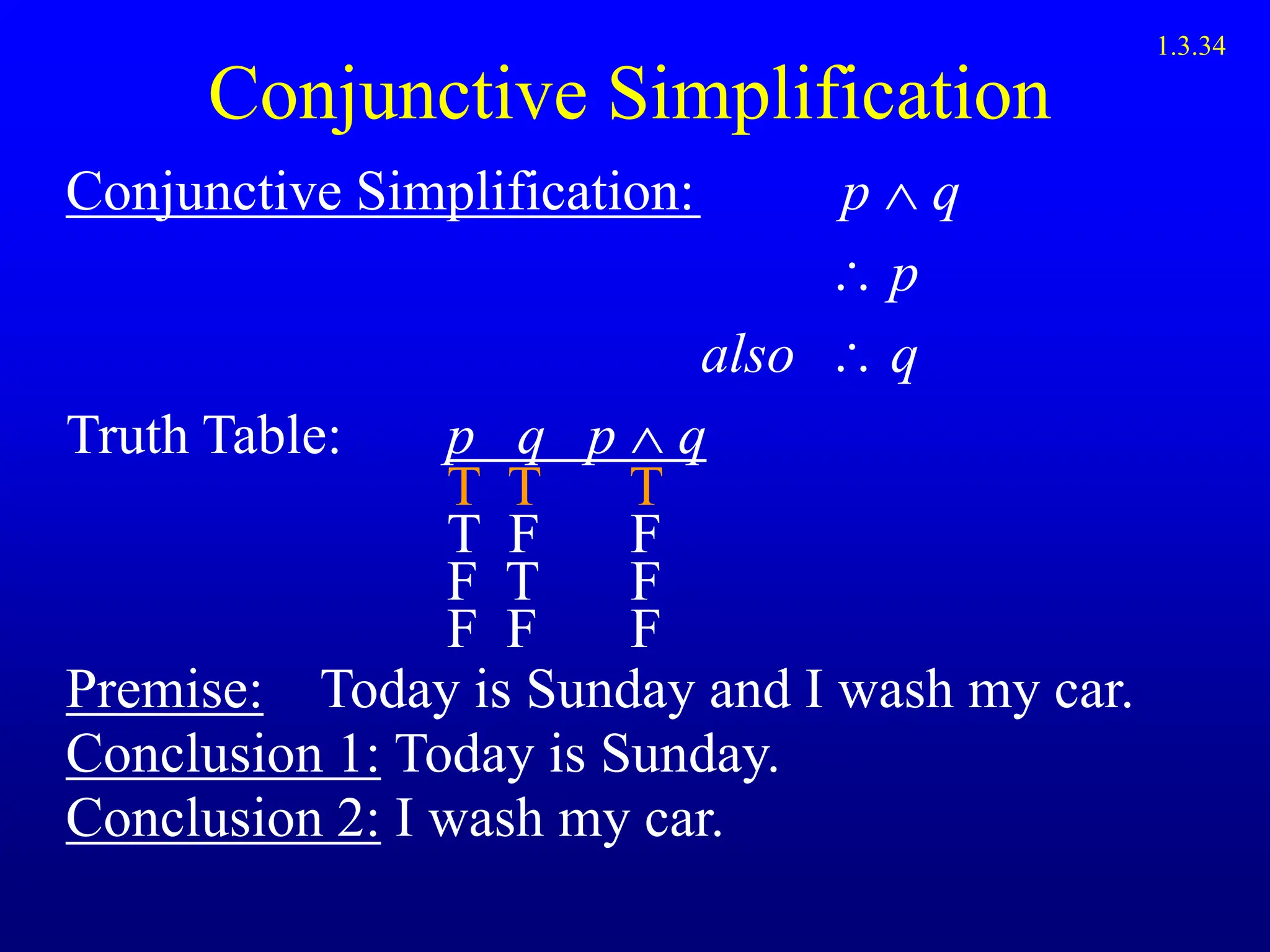

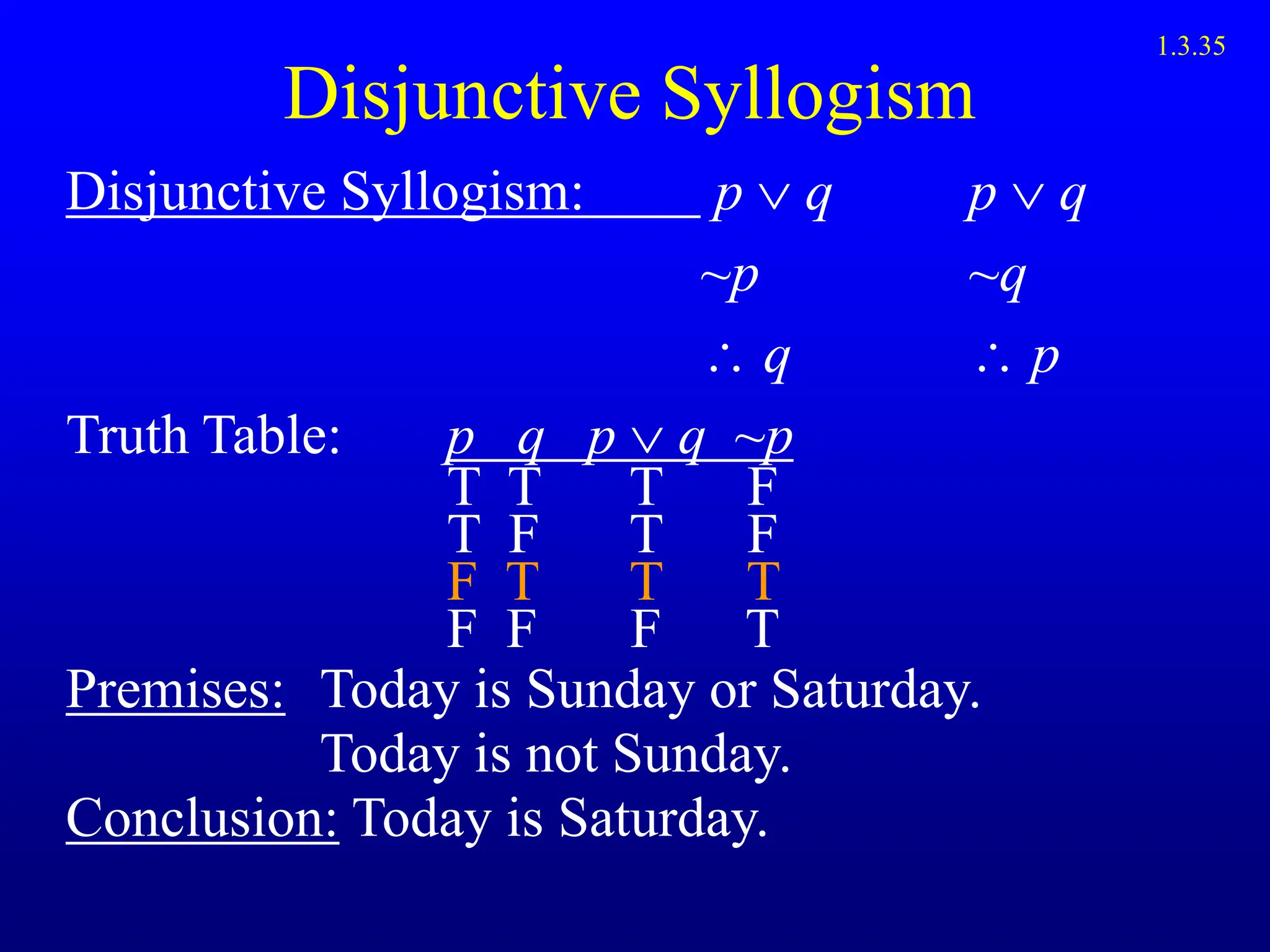

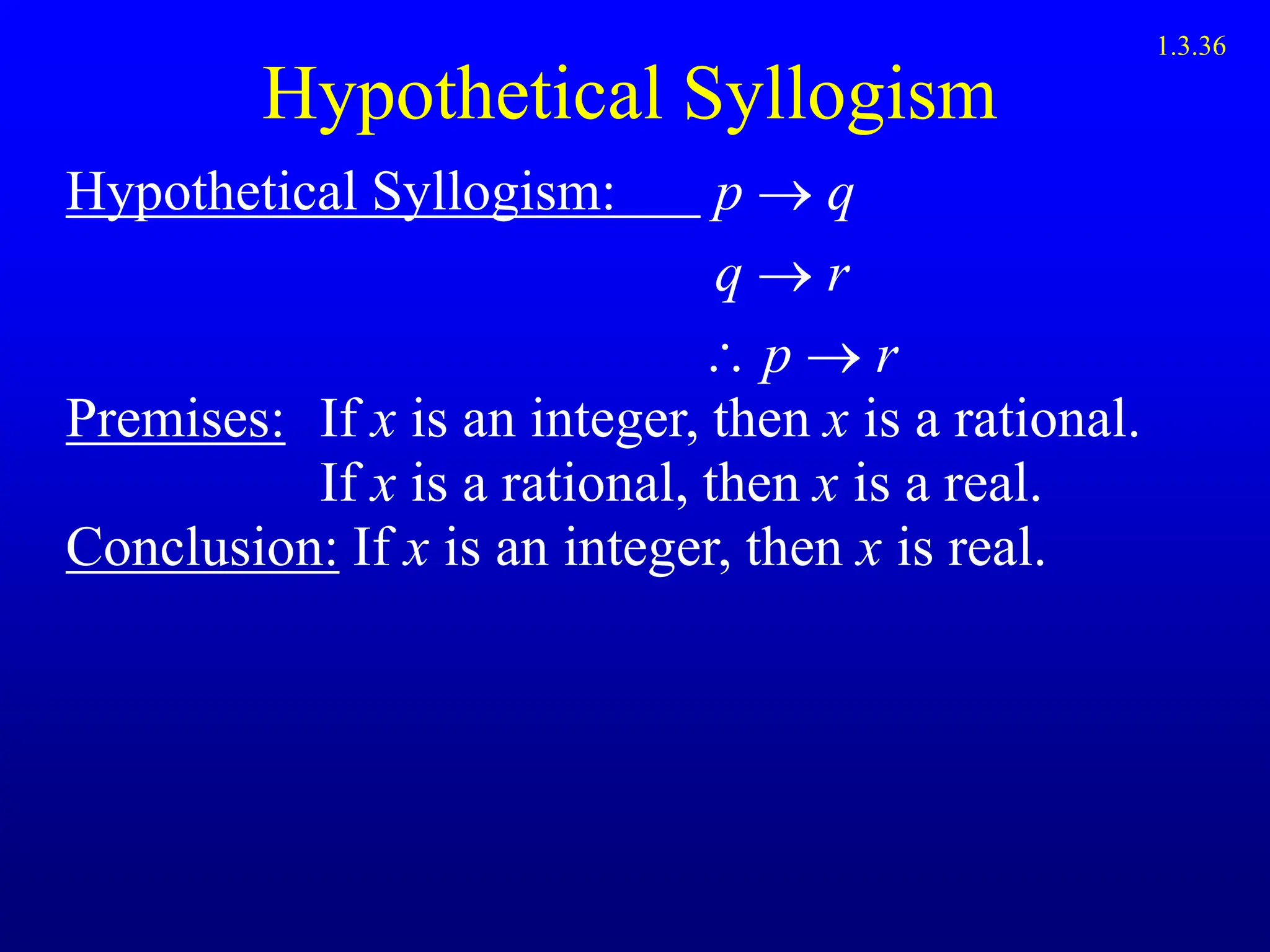

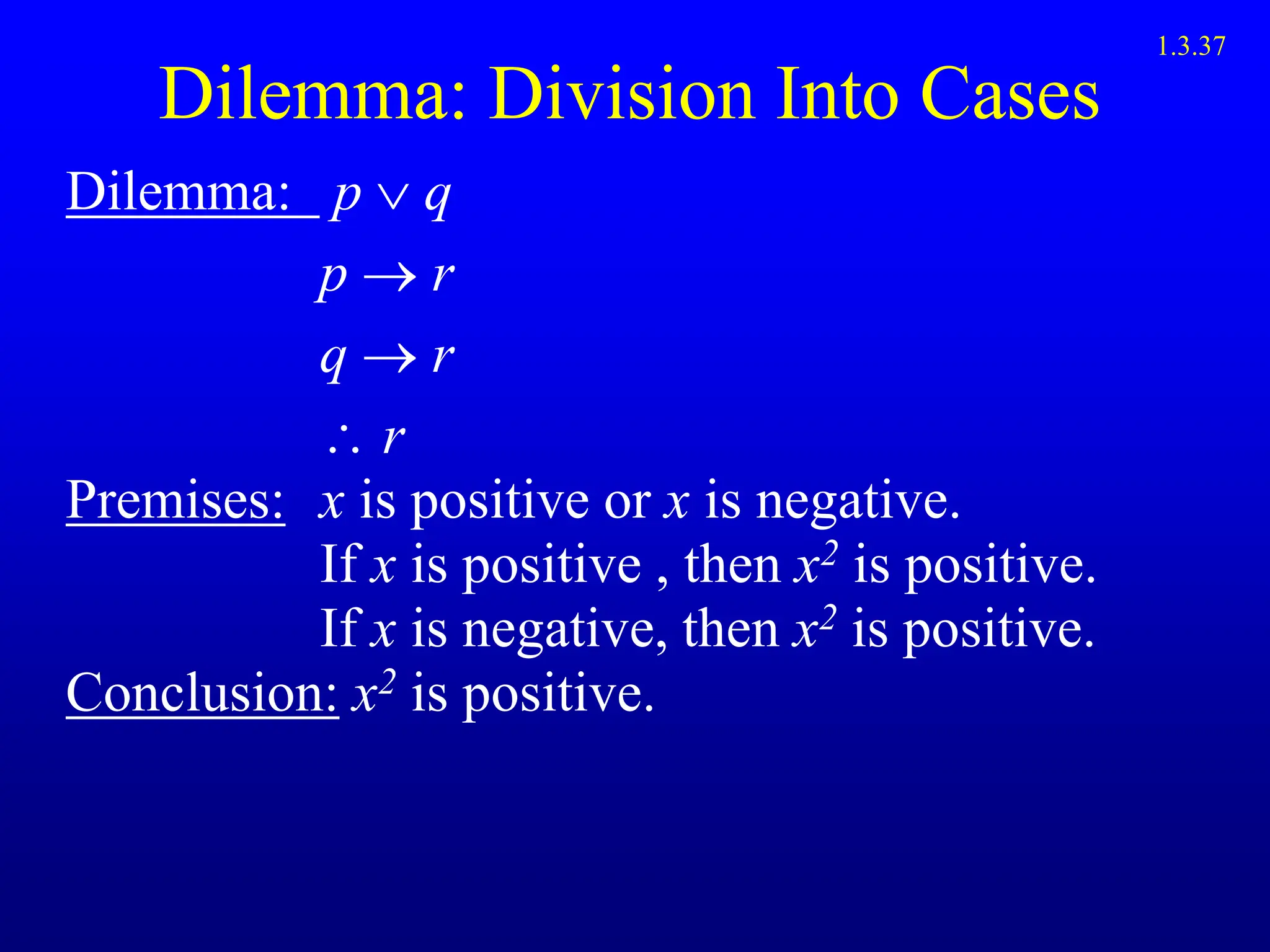

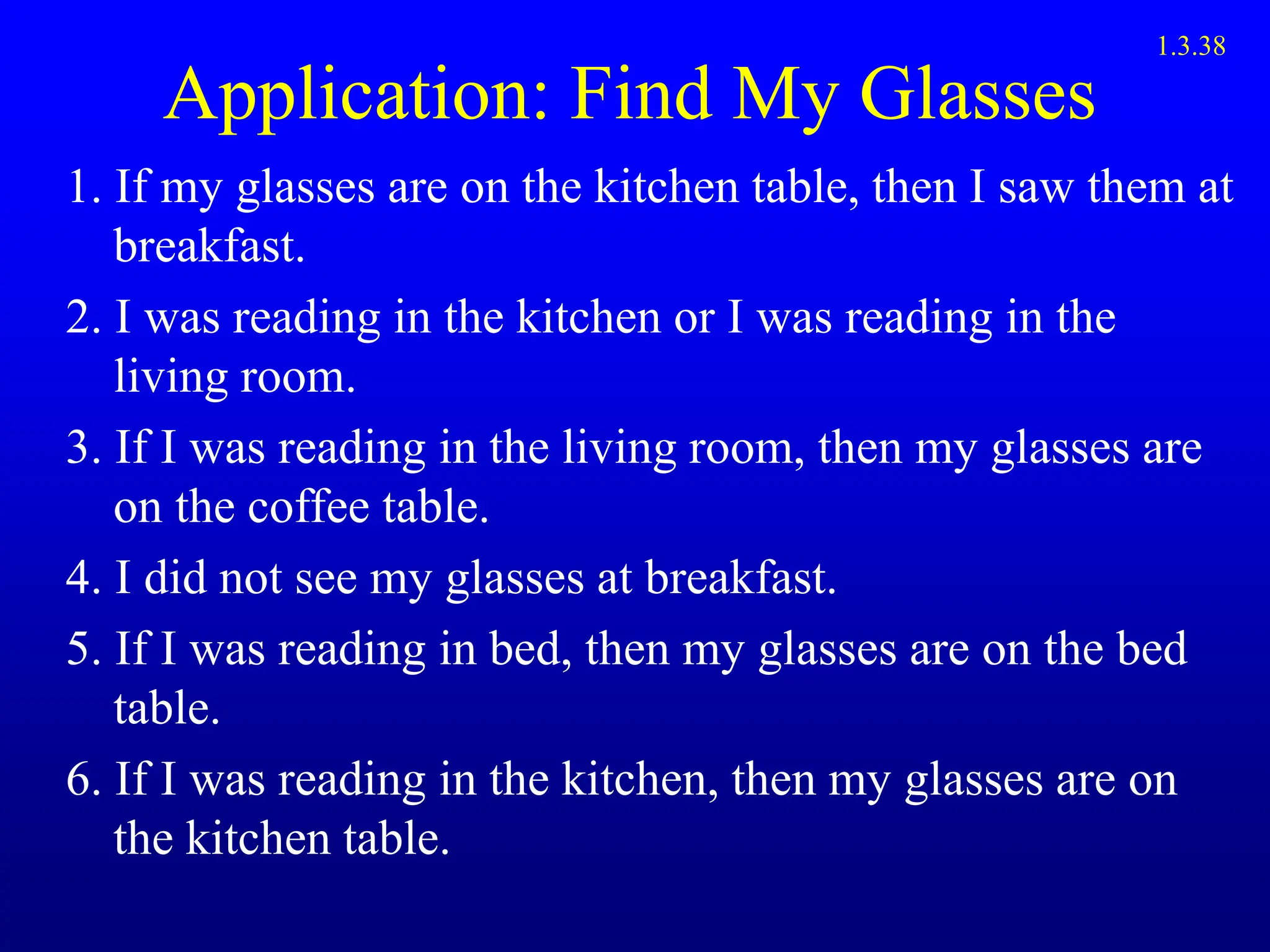

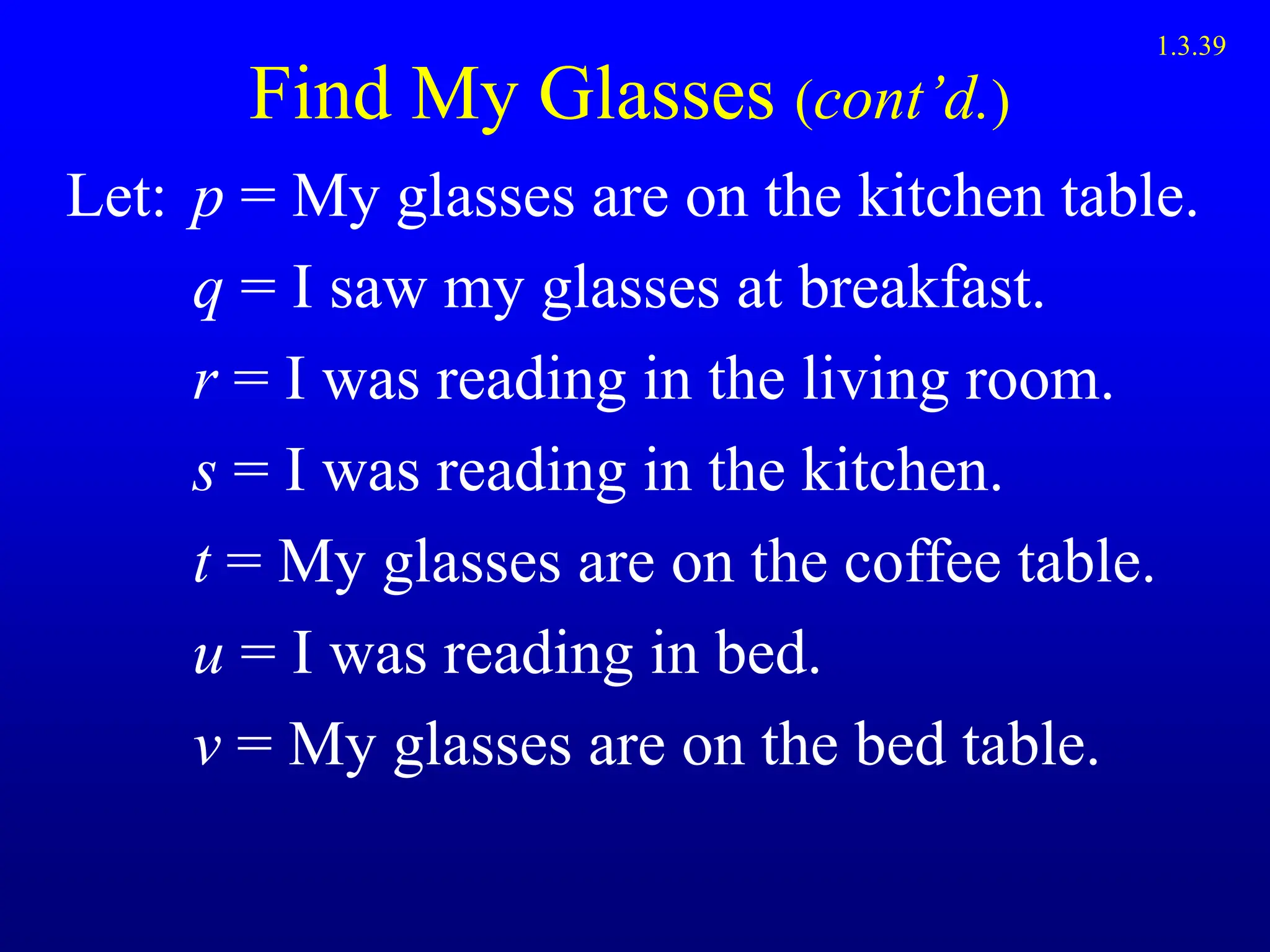

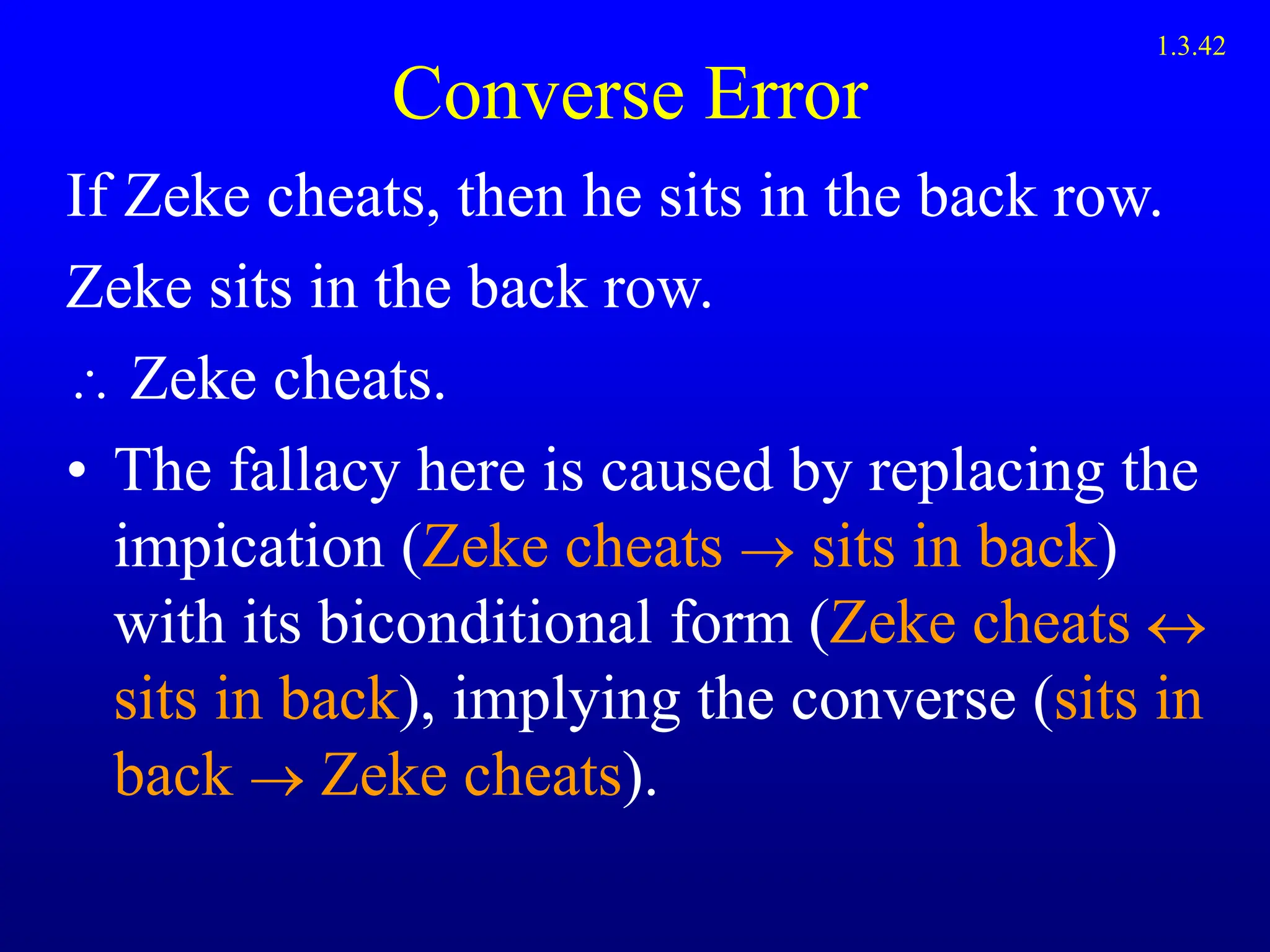

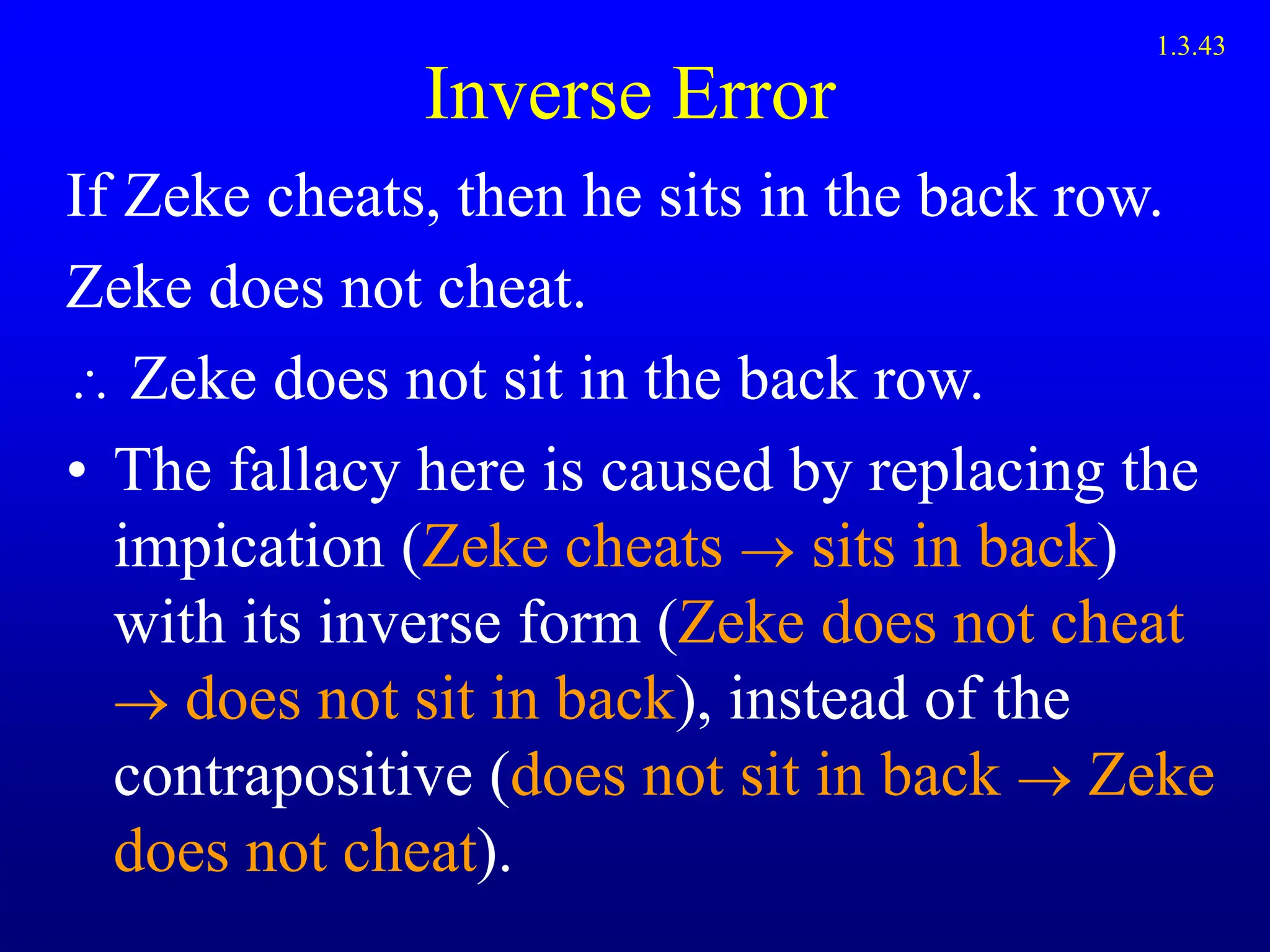

The document covers key concepts in symbolic logic such as logical operations, truth tables, tautologies, valid and invalid arguments, and special valid argument forms. Logical equivalence and valid argument forms like modus ponens, modus tollens, disjunctive syllogism and hypothetical syllogism are explained. Examples are provided to illustrate logical statements, truth tables, and how to determine if an argument is valid or invalid.

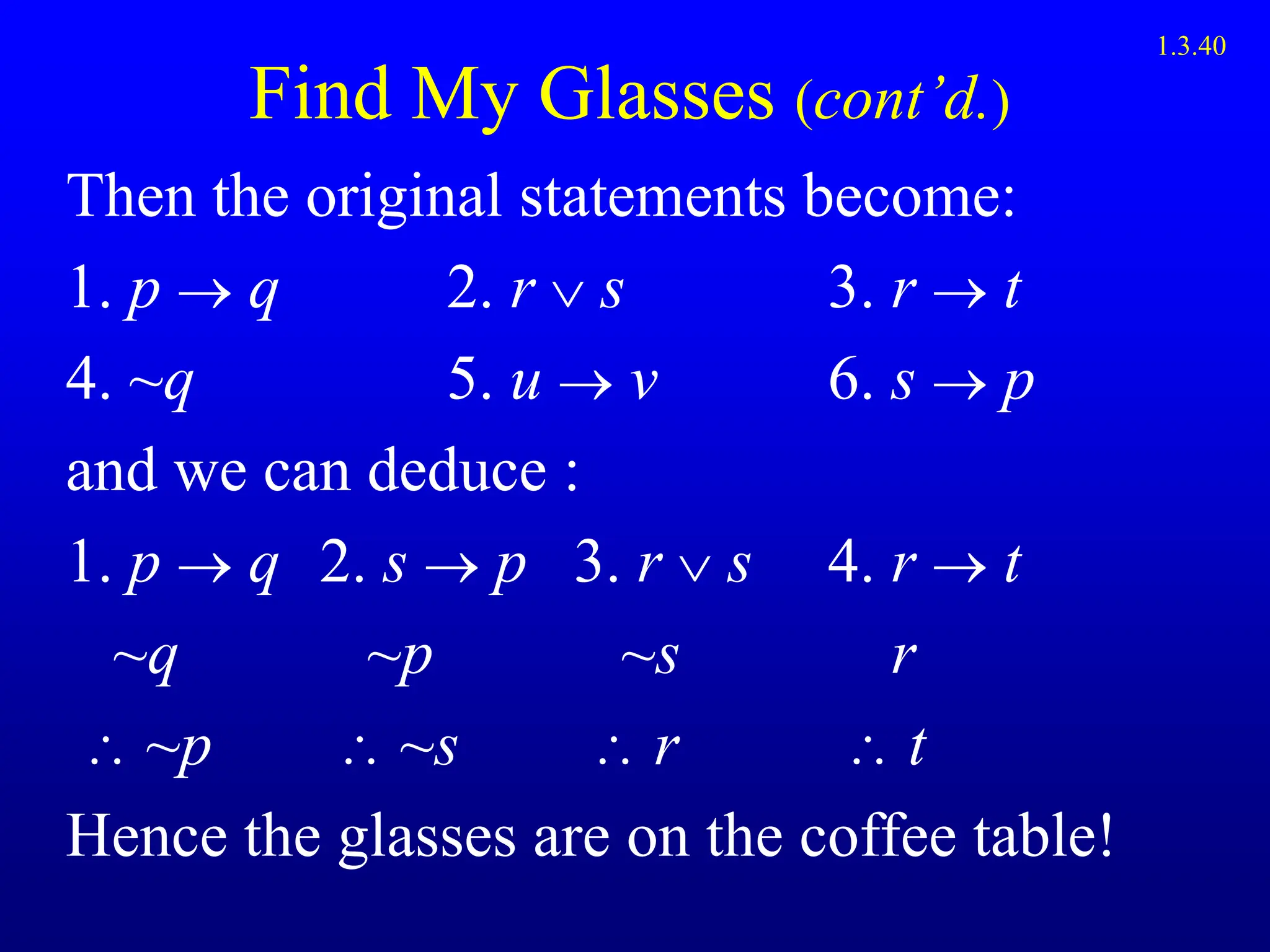

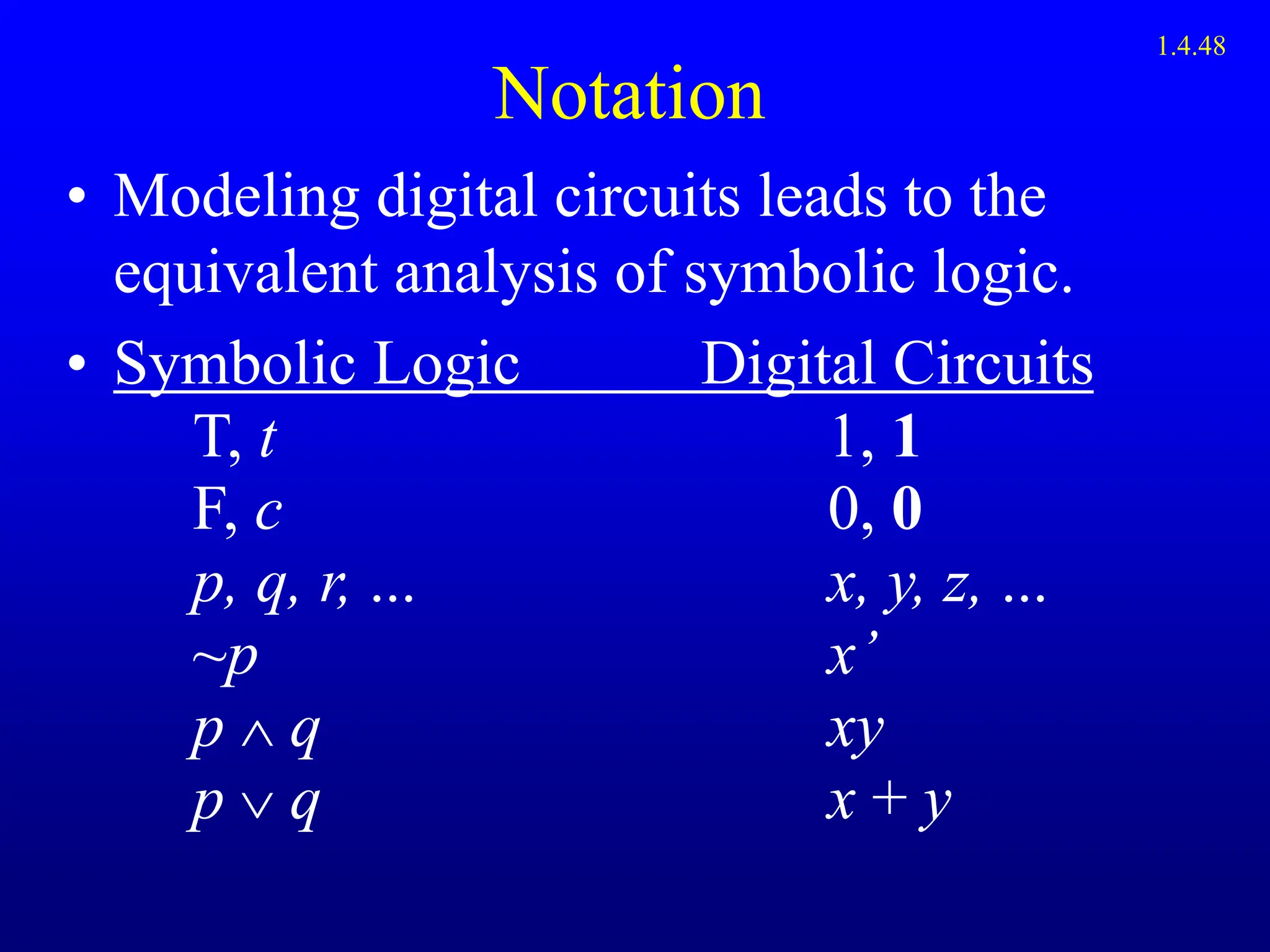

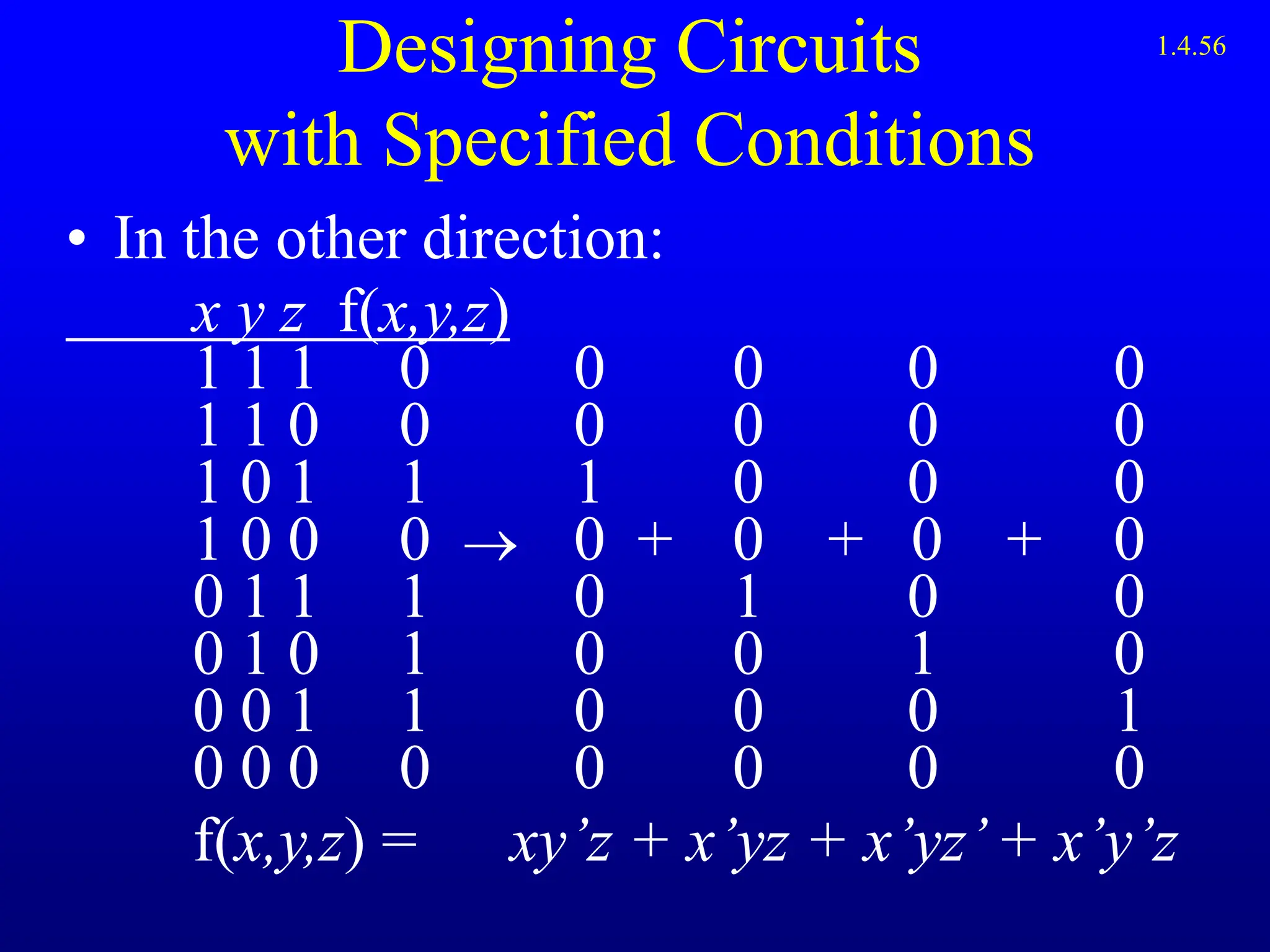

![A Valid Argument

p (q r)

~r

(p q)

Truth Table: p q r [p (q r)] ~r (p q)

T T T T F T

T T F T T T

T F T T F T

T F F T T T

F T T T F T

F T F T T T

F F T T F F

F F F F T F

1.3.29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/logiclec4-240124052132-e983f5f3/75/logic_lec4-ppt-29-2048.jpg)

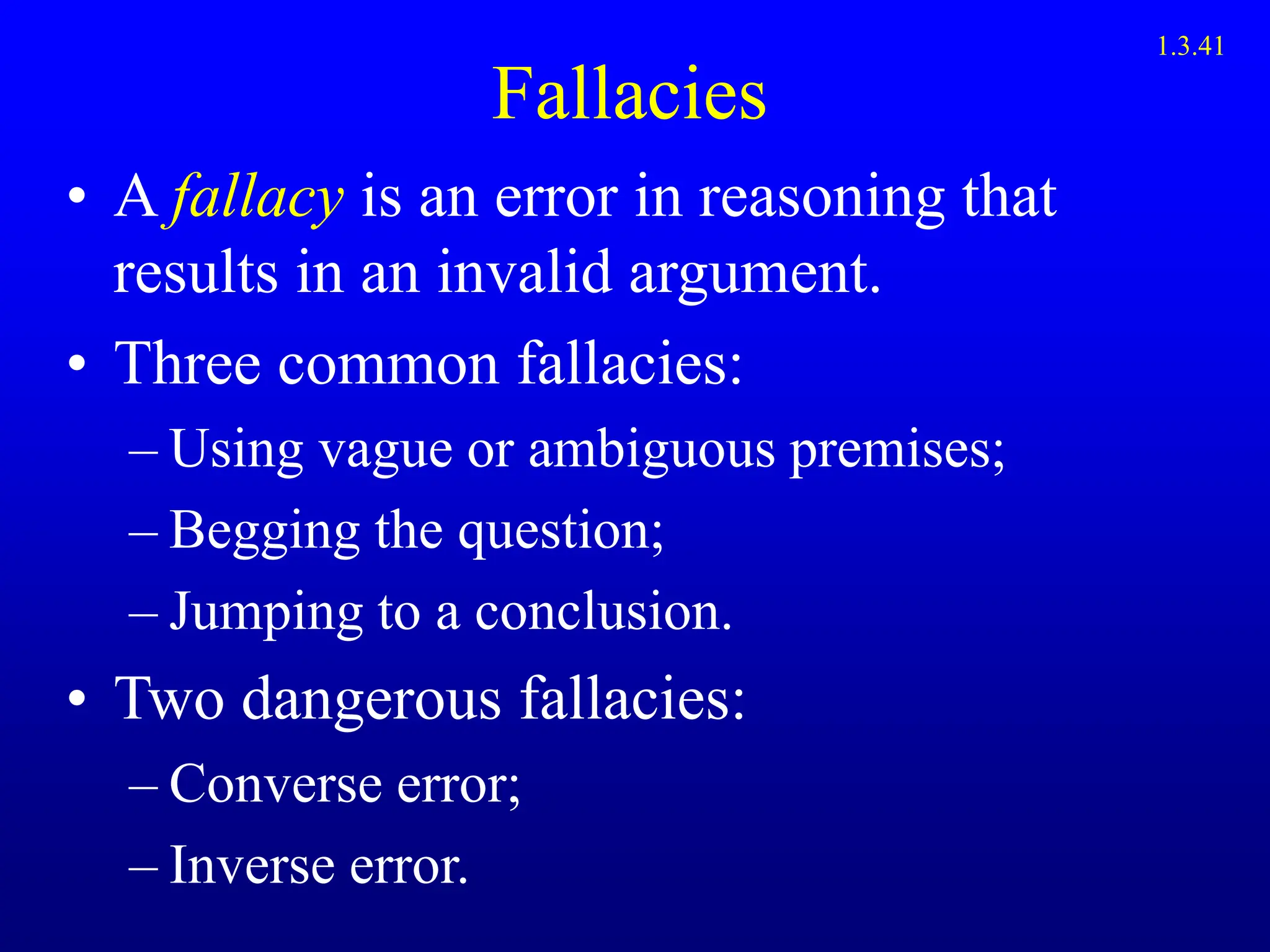

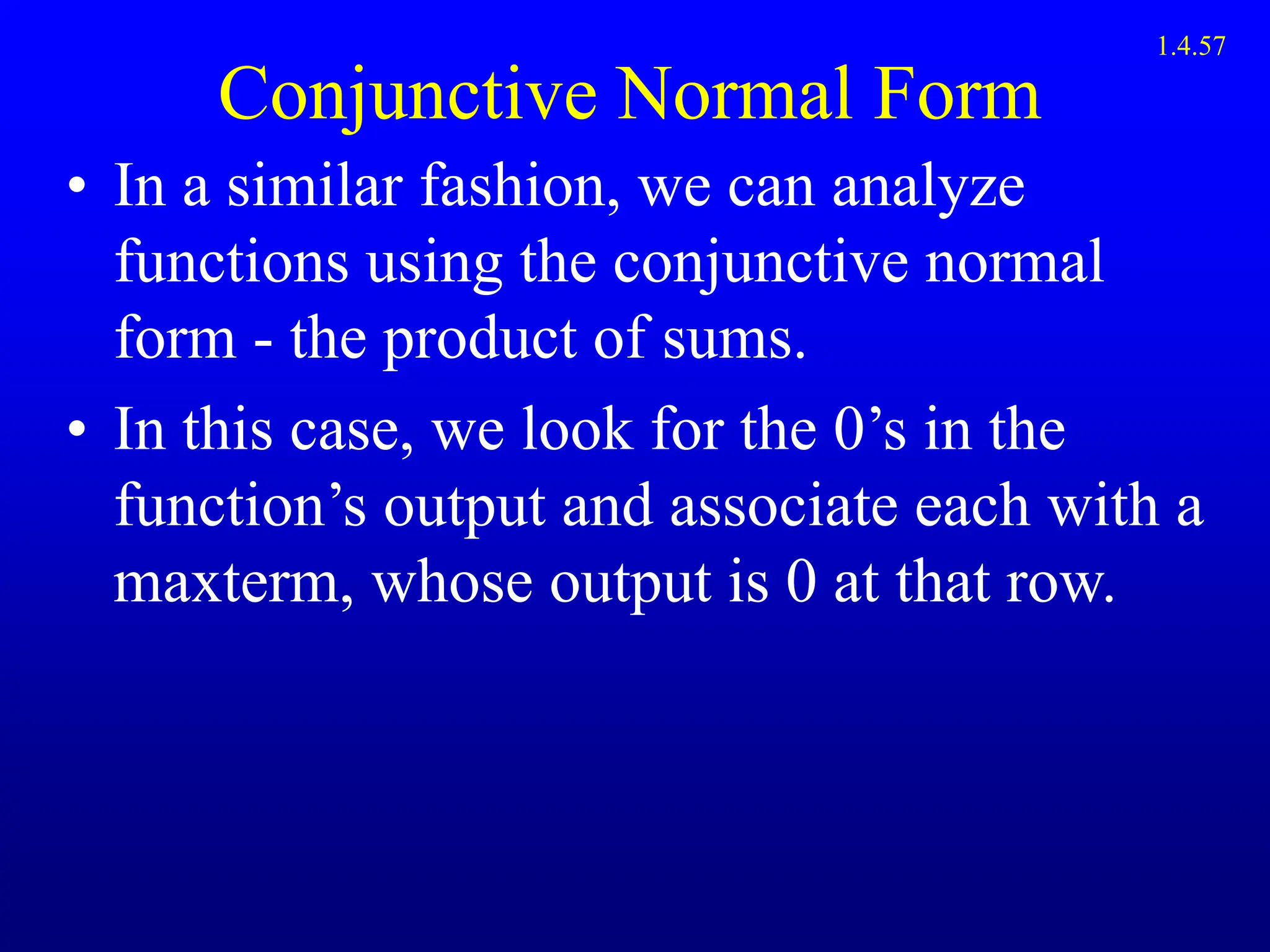

![An Invalid Argument

p (q r)

~r

(p r)

Truth Table: p q r [p (q r)] ~r (p r)

T T T T F T

T T F T T T

T F T T F T

T F F T T T

F T T T F T

F T F T T F

F F T T F T

F F F F T F

1.3.30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/logiclec4-240124052132-e983f5f3/75/logic_lec4-ppt-30-2048.jpg)