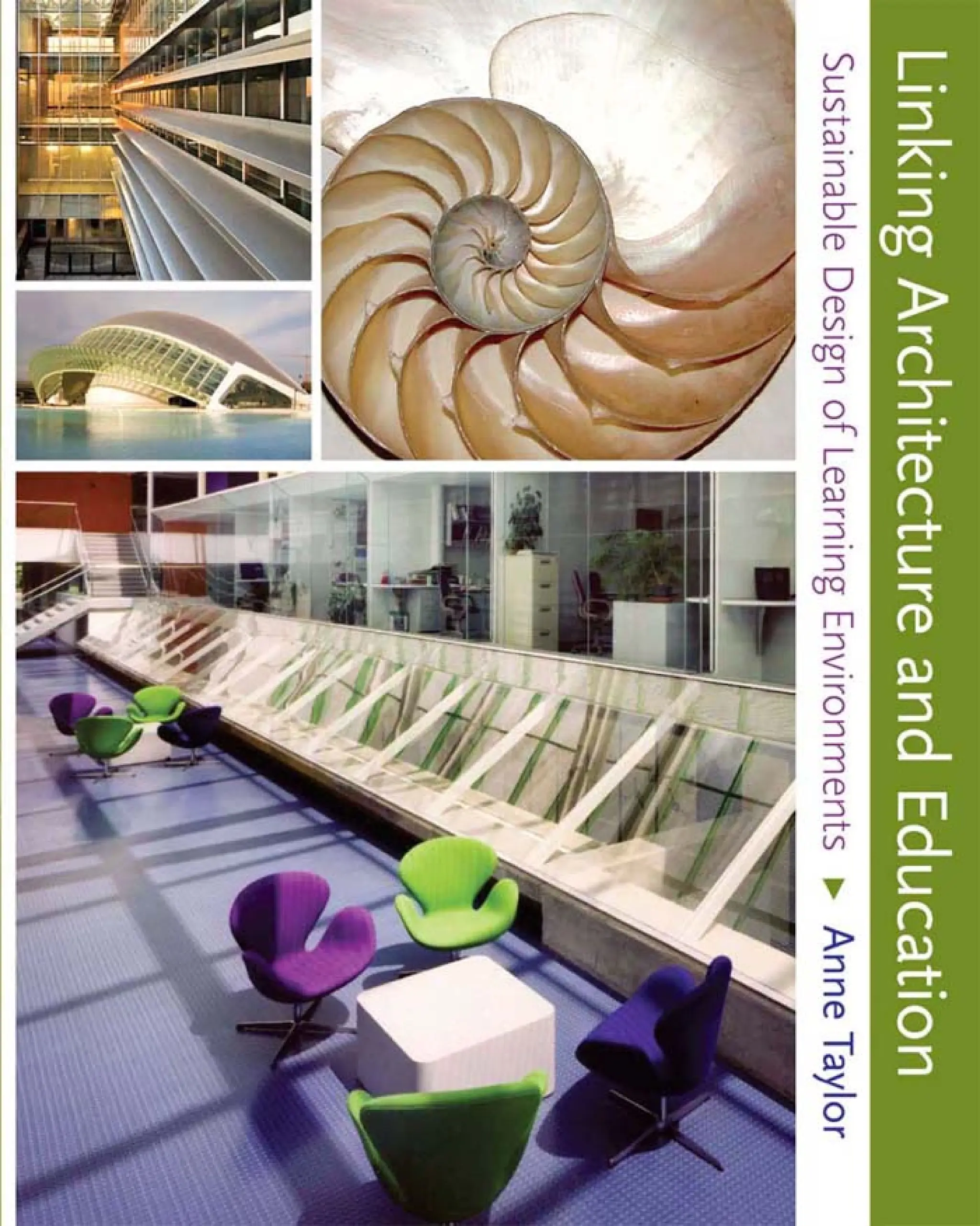

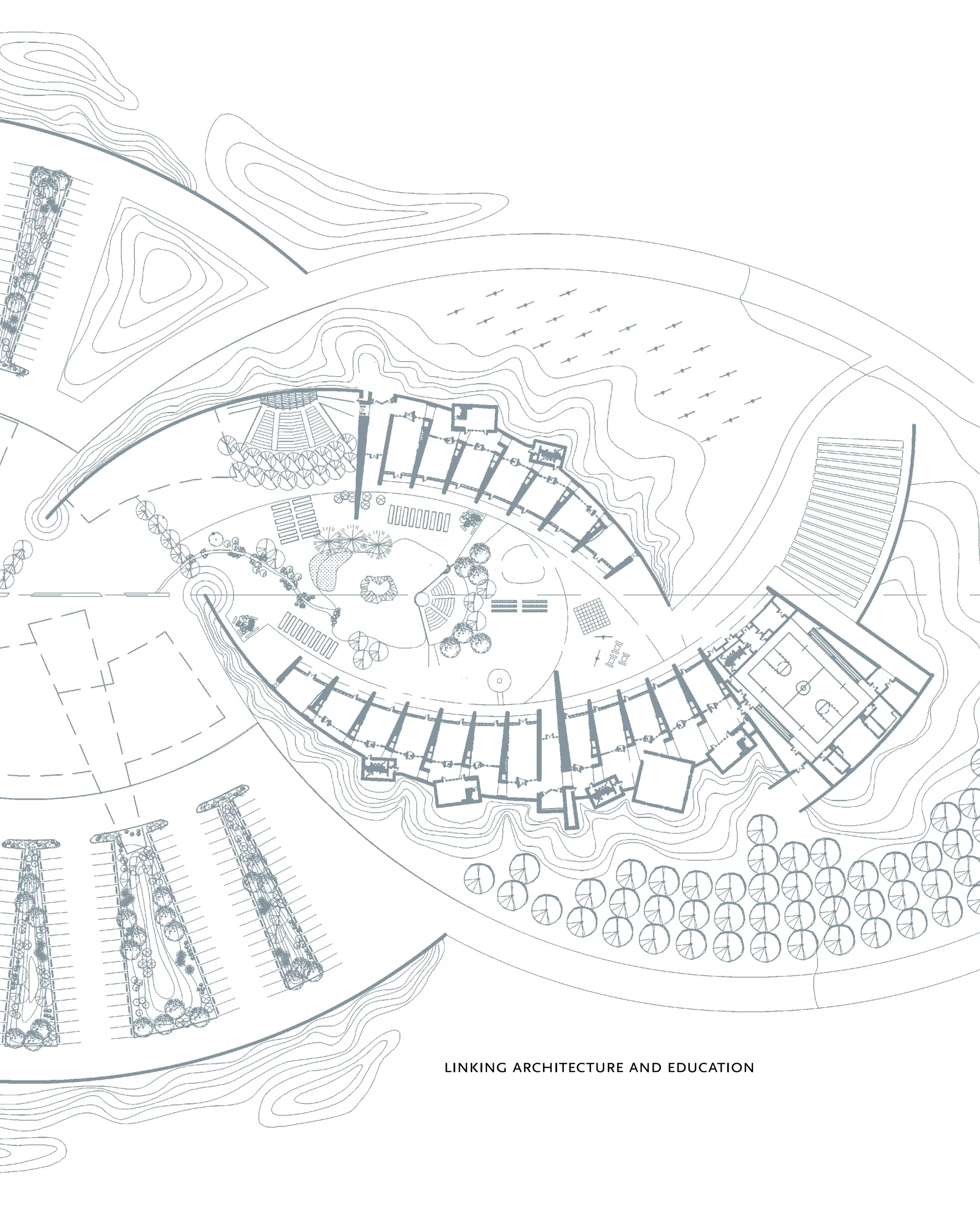

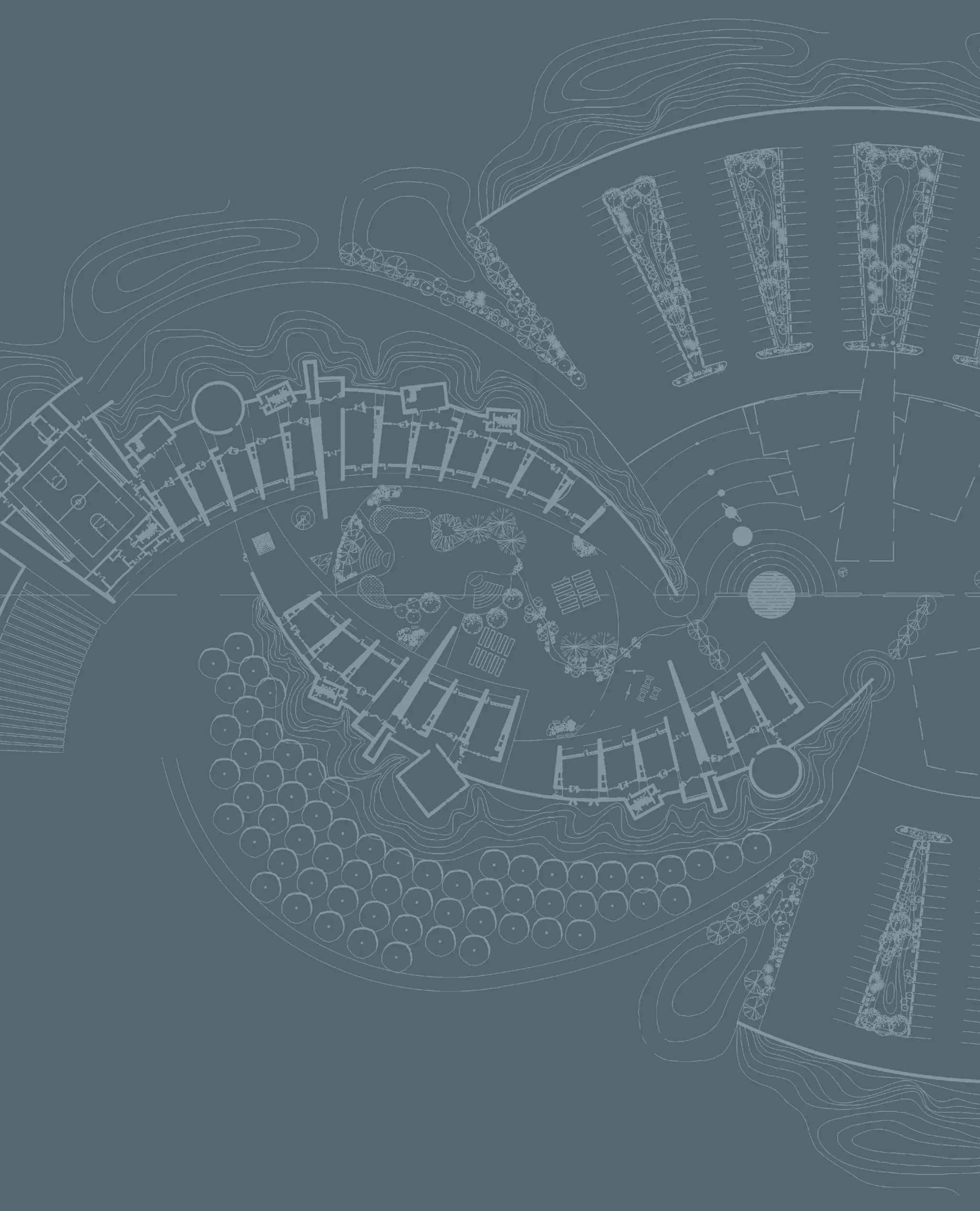

Linking Architecture And Education Sustainable Design Of Learning Environments Anne Taylor

Linking Architecture And Education Sustainable Design Of Learning Environments Anne Taylor

Linking Architecture And Education Sustainable Design Of Learning Environments Anne Taylor