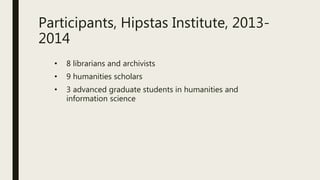

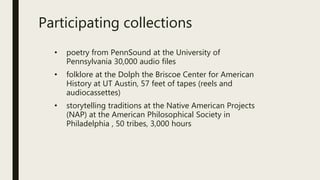

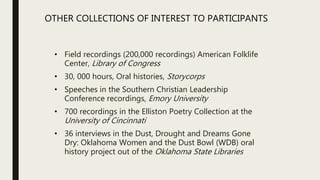

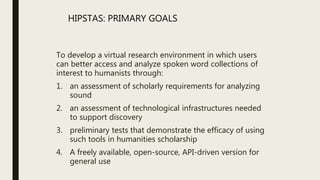

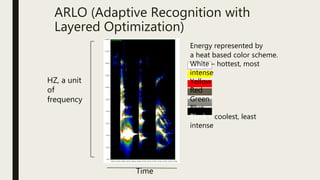

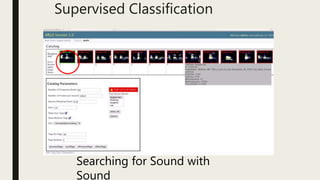

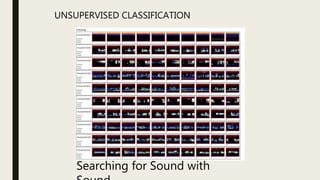

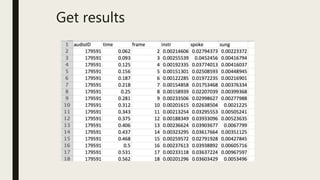

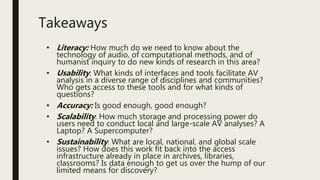

This document discusses using computational tools to analyze and provide access to large audiovisual collections. It describes a project called HiPSTAS that developed the open-source ARLO tool to analyze 68,000 hours of audio content using speech-to-text transcription, audio waveform analysis, and machine learning. The goal was to assess how these tools could help humanities scholars better access spoken word collections. Key challenges discussed include balancing accuracy with efficiency and ensuring tools are accessible and usable across disciplines.

![HiPSTAS team

• Tanya Clement, [PI] Assistant Professor, University of

Texas at Austin

• Loretta Auvil [Co-PI] Senior Project Coordinator at the

Illinois Informatics Institute (I3) at the University of

Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

• David Tcheng [Co-PI] Research Scientist at I3; ARLO

developer

• Tony Borries, Research Programmer working as a

consultant with I3; ARLO programmer

• David Enstrom, Biologist, University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign; consultant](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fiat2016ced-181212181347/85/Let-the-Computer-Do-the-Work-13-320.jpg)