This document summarizes the design and testing of a fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) for low altitude surveillance missions. The UAV was designed with an aerodynamic glider configuration and powered by a 200 W polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell system fed by a chemical hydride hydrogen generator, along with lithium polymer batteries. Bench and flight tests showed the hybrid power system enabled flight durations of nearly 4 hours. The document discusses the aircraft design process, onboard power system, results from testing, and lessons learned for optimizing long endurance fuel cell powered UAVs.

![A fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle for

low altitude surveillance missions

N. Lape~

na-Rey a,*

, J.A. Blanco a

, E. Ferreyra a

, J.L. Lemus a

, S. Pereira,

E. Serrot a

a

Boeing Research & Technology Europe, S.L.U, Spain

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 31 August 2016

Received in revised form

20 January 2017

Accepted 24 January 2017

Available online xxx

Keywords:

Unmanned aerial vehicle

Polymeric electrolyte membrane

fuel cell

Hydrogen

Hybrid power management

Sodium borohydride

Long endurance

a b s t r a c t

Boeing Research & Technology Europe has designed, developed and subsequently bench

and flight tested, in a wide range of different operative conditions, an electric Unmanned

Air Vehicle (UAV) powered by a hybrid energy source. The energy source features a 200 We

Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) fuel cell system fed by a chemical hydride hydrogen

generator that produces highly pure hydrogen at the fuel cell operating pressure from the

controlled hydrolysis of Sodium Borohydride (NaBH4), resulting in 900 Wh of energy from

1 L of chemical solution. Equipped also with high specific energy Lithium Polymer batteries,

this fuel cell powered UAV is able to achieve flight durations close to 4 h.

This paper summarizes the aircraft and systems design, the results of the bench and

flight tests along with the main challenges faced during this development and the lessons

learned for future optimization.

© 2017 Hydrogen Energy Publications LLC. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Electric propulsion for mini-UAVs (Unmanned Air Vehicles

with Maximum Take of Weight, MTOW, below 25 kg) provides

a route for lower capital cost, reduced carbon footprint and

quieter Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) operations. However,

state-of-the-art advanced lithium polymer battery technology

offers limited specific energy, which provides a typical mini-

UAV with an endurance of 60e90 min and, therefore, limits

the flight mission or increases operational costs [1,2].

Combining batteries and fuel cells in hybrid propulsion

systems can significantly increase the UAV's endurance,

opening new mission capabilities not previously possible for

electric mini-UAVs [3e5]. Indeed, UAVs with MTOW below

25 kg are a niche application in which air cooled PEM fuel cells,

in their current maturity stage, already meet the weight tar-

gets while offering unique competitive advantages over con-

ventional power sources including: low noise and vibration so

the airplane can fly at lower altitudes without being discov-

ered and use simpler cameras, environmental benefits (no

greenhouse gases, GHG, emissions) and low thermal signa-

ture. Moreover, electric motors are more efficient and have far

better reliability than their non-electric counterparts.

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: nieves.lapena@boeing.com (N. Lape~

na-Rey).

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/he

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f h y d r o g e n e n e r g y x x x ( 2 0 1 7 ) 1 e1 5

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.137

0360-3199/© 2017 Hydrogen Energy Publications LLC. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Please cite this article in press as: Lape~

na-Rey N, et al., A fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle for low altitude surveillance

missions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.137](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-230206105836-a236b105/75/j-ijhydene-2017-01-137-pdf-1-2048.jpg)

![During the last decade the UAS industry has grown sub-

stantially, mainly through the development and maturation of

military applications, followed by a wide range of civil appli-

cations, such as: border control, coastguard, law enforcement

and police support, power line, water pipes and gas pipes

monitoring, terrain surveillance, environmental surveillance,

communications, etc. Market and application research seems

to show a growing trend towards mini-UASs mainly due to

lower cost and investment risk, along with less infrastructural

needs for tactical surveillance. The selection of this specific

type of UAVs would facilitate the upcoming certification pro-

cess and a larger number of fuel cell powered UAVs is expected

in the near future. Numerous flight demonstrations of hybrid

FC/battery-powered UAVs have been reported in recent years

from universities, research organizations and commercial

entities across the world for low and high altitude surveillance

[6e21]. Some of the prototypes that have successfully

demonstrated the feasibility of this application include: the

Global Observer [6], a high altitude long endurance (HALE) UAV

developed by AeroVironment (USA 2005); the mini-UAV

developed by Georgia Technical University [7] (USA, 2006);

the Spider-Lion [8], a micro-UAV developed by The Naval

Research Laboratory (USA, 2006); the Hyfish [9], a mini-UAV

developed by DLR & Horizon Energy Systems (Germany,

2007); the SAE Pterosoar [10] (California State University,

Oklahoma State University, Horizon Energy Systems, USA,

Nov 2007), the Puma [11] (AeroVironment & Adaptive Materials

Inc e SOFC, June 2007), the Endurance (Solar Bubbles &

Adaptive Materials, Inc., October 2008) [12], the Boomerang®

[13] (BlueBird Aero Systems & Horizon Energy Systems), which

was presented at the “Unmanned Systems 2009” conference,

and the WanderB®

[14] (BlueBird Aero Systems & Horizon En-

ergy Systems), capable of 10h endurance flights. The longest

endurance unofficial record is held by the Ion Tiger of The

Naval Research Laboratory (NRL's), Protonex Technology Cor-

poration, the University of Hawaii, and HyperComp Engi-

neering, which flew 48 h and 1 min in 2013 [15,16]. Other recent

demonstrations include: the first fuel cell powered unmanned

aerial vehicle (UAV) flights in India carried out by the Canadian

fuel cell specialist EnergyOr Technologies Inc. in collaboration

with Radiant Coral Digital Technologies (RCDT), an Indian

technology and engineering company that provides products

and services to the aerospace and defense sectors [17]; the

research done at Loughborough University UK (Skywalker X8)

using ArduPilot's autonomous take-off [18]; the automatically

controlled Thunderbird” (LN60F) UAV sponsored by the China

Aviation Industry Group and independently developed by

Liaoning General Aviation Academy [19] (the aircraft wingspan

width is 10.5 m, weights 257 kg with a cruise speed of 120 km/h

and the endurance was 4 h) or the UAV of KIMS (The Korean

Institute of Materials Research) [20]; finally, an electric proto-

type of one of the commercially available UAVs with longer

proven operation in real flight missions, the InSitu ScanEagle,

also successfully completed its first hydrogen-powered fuel

cell flight (two-and-a-half-hour flight test) making an impor-

tant step in the move toward hydrogen-powered fuel cell so-

lutions as an alternative to expensive gas and heavy fuel

solutions in UAVs [21]. The Naval Research Laboratory (NRL)

and United Technologies (UTC) took UTC's 1500 W (2 HP) fuel

cell and integrated it with NRL's hydrogen fueling solution into

a ScanEagle propulsion module. It is worth mentioning that

most of these developments are not well documented and,

thus, the characteristics, the performance, the reliability, the

practicality or the technology readiness level of the electric

propulsion systems used are not well known. In most cases,

the hydrogen generation or storage method is not even

mentioned. Finally, the capabilities of the UAVs (ceiling, power

consumption, flight speed, payload capability, etc.) are not

well known either.

To date, PEM fuel cells relying on hydrogen as fuel have

been most commonly used in mini-UAVs, mainly due to their

lower operating temperature (thus, low thermal signature)

and relative compactness compared to other types of fuel

cells. The majority of PEM fuel cell/Li ion batteries-powered

systems tested to date rely on compressed gas cylinders

which are delivered to the UAV user's location (and used to

refill the UAV hydrogen tanks on-site with a compressor) or

chemical hydride systems to produce hydrogen on-board.

The former option presents challenges related to safety,

fuel availability on site, limited UAV on-board storage capa-

bility (thus, compromising the UAV endurance), excessive

fuel costs (due to fuel transport to remote locations) and

unknown carbon footprint. On the other hand, most of the

chemical hydride systems developed so far still pose chal-

lenges related to low ambient temperature operation, by-

product disposal and, thus, UAV's weight loss (i.e., center of

gravity shift) during flight; also reliability and ability to scale

up (and therefore maximize the UAV flight endurance) are

yet to be demonstrated. Finally, the high maintenance

currently required needs to be decreased to make the tech-

nology more user friendly. However, once matured, this

technology would offer an excellent option for operation in

remote areas.

Aircraft and onboard systems design

Aircraft design

The ideal airframe configuration is that with very high aero-

dynamic efficiency and enough internal volume to accom-

modate the fuel cell system and the fuel system. It is worth

mentioning that, contrary to the fuel cells in this particular

power range, hydrogen based fuel systems are not yet opti-

mized in terms of weight and volume for most aeronautical

applications.

Fig. 1 e Aircraft design.

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f h y d r o g e n e n e r g y x x x ( 2 0 1 7 ) 1 e1 5

2

Please cite this article in press as: Lape~

na-Rey N, et al., A fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle for low altitude surveillance

missions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.137](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-230206105836-a236b105/85/j-ijhydene-2017-01-137-pdf-2-320.jpg)

![fuel cell), the propulsion system (the electronic speed

controller or ESC and the electric motor) and a telemetry

system (to download data from the fuel cell system and other

sensors).

The fuel Cell/LiPo hybrid power source included a

commercially available fuel cell system from Horizon Energy

Systems, commercially available Lithium Polymer batteries

and a hybrid power management card designed also by Ho-

rizon Energy Systems. This system was chosen because it is

one of the most lightweight and compact commercially

available systems for this power range. A small fraction of a

typical UAV mission, mainly takeoff and climb stages, de-

mand an amount of power meaningfully higher than that for

the rest of the flight. To optimize the weight of the overall

system, the fuel cell was sized mainly for cruise flight whereas

the batteries provided the additional power required for

takeoff and climb as well as the power for transitory high-

powered maneuvers. The hybrid power management board

performs two tasks:

1. Merges the Lithium Polymer battery (5000 mh 6S 20C)

power and the fuel cell power directly into the propulsion

system, thanks to a high power Schottky diode.

2. Charges the lithium-polymer battery whenever there is a

surplus of energy generating capacity at the fuel cell and

the battery voltage is below a certain threshold.

The commercially available 200 We output rate fuel cell

system (Fig. 12 and Ref. [27]) had a rated capacity of 900 Wh

using 1 L of a solution of 20% wt. NaBH4 in water, and a fueled

weight close to 2.5 kg, including Thunderpower Lith-

iumePolymer batteries and the fuel generating cartridge. The

fuel cell stack produces electricity, water and heat from the

electrochemical reaction of the highly pure hydrogen,

generated from the controlled hydrolysis of NaBH4, and oxy-

gen from the air. Section 3 provides further details of the fuel

cell system.

The propulsion block consisted of the ESC and the electric

motor. The cruise speed was calculated for a 18.5 1200

pro-

peller turning at around 3200 rpm in-runner brushless motors

that provide such low speeds are very difficult to find, so a

combination with gearbox was necessary. The option selected

was the lightest, comprising a Hacker B50 19S electric brush-

less motor and a 6.7:1 gearbox integrated with the motor

(weighting 198 g in total). After the first battery flight tests in

which several propellers were tested, the initial calculations

proved to be optimum.

The electronic speed controller chosen was the Castle

Creations Phoenix ICE Lite 50, capable of withstanding a cur-

rent of 50 A, that is, 1200 W at 24 V weighing only 48 g. Its

Table 2 e Chosen energy storage systems.

Source Weight (kg) Maximum power (W) Energy (Wh) Power density (W/kg) Energy density (Wh/kg)

Fuel cell system 2 200 900 100 450

LiPo battery 0.8 2200 110 2750 138

Control LiPo battery 0.4 222 74 555 185

Fig. 11 e Propulsion block diagram.

Fig. 12 e Fuel cell system (200 We fuel cell

system þ 900 Wh H2 generator from NaBH4).

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f h y d r o g e n e n e r g y x x x ( 2 0 1 7 ) 1 e1 5

6

Please cite this article in press as: Lape~

na-Rey N, et al., A fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle for low altitude surveillance

missions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.137](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-230206105836-a236b105/85/j-ijhydene-2017-01-137-pdf-6-320.jpg)

![weight is important since its position is far from the center of

gravity of the plane. The speed signal that comes from the

control block (see Section 2.2.1) was connected to this device

through an optocoupler to keep the blocks electrically

isolated.

The chosen telemetry system was a commercially avail-

able EagleTreeSystems set that allows First Person View (FPV)

with an On Screen Display (OSD) which indicates GPS data,

airspeed, heading, barometric altitude, propeller rpms and

outside air temperature and motor temperature and electric

indications, such as power and battery voltage. All the

telemetry data was both recorded in an on-board logger and

also sent to ground were a dedicated computer displayed and

recorded the values for later analysis and redundancy. These

indicators are essential for the pilot to control the plane and

also for the rest of the flight tests crew to calibrate the auto-

pilot's parameters and monitor the flight progress. The video

transmitter was placed on a custom made heat sink that was

placed where the normal flight air-flow could cool the whole

system. Its transmission band was centered in 1.2 GHz.

The fuel cell stack electronics provided an RS-232 serial

output that was sent to the ground control station via an

audiomodem designed and developed by BRTE for that

purpose. The audio generated at this audiomodem was sent

via the video transmitter audio channel.

Fuel cell system

Fuel cell stack

The application of the PEM fuel cells as a primary power

source in electric vehicles has received increasing attention in

the last few decades, mainly in the car industry. PEM fuel cells

use a dense and gas tight polymer membrane electrolyte,

which conducts hydrogen ions in a certain range of temper-

ature and humidity. On the contrary, both the anode and the

cathode are porous. The advantages of PEM fuel cells are that

the production of the cell is simple, they are able to withstand

large pressure differentials, material corrosion problems are

minimal, and they have demonstrated long life in several

stationary and transport applications.

In this type of fuel cell, hydrogen from the fuel gas stream

is consumed at the anode, yielding electrons that go through

an external circuit and hydrogen ions which go through the

electrolyte towards the cathode [22,23]. There, the protons

combine with the oxygen from the air and the electrons to

produce water.

Anode: 2H2 / 4Hþ

þ 4e

Cathode: O2 þ 4Hþ

þ 4e

/ 2H2O

Thus, the only product of the reaction is water, which does

not dissolve in the electrolyte and is, instead, expelled from

the cathode into the oxidant gas stream. As the PEMFC oper-

ates in the 60e70

C temperature range, this water is pushed

out of the fuel cell by the excess oxidant flow.

An open cathode stack was chosen (Fig. 13) mainly because

it was commercially available, thus, helping to reduce the cost

of the project, and also because, in general, it is suitable for

low altitude flight surveillance missions (below 1000 m). The

stack can deliver up to 10 A in a voltage range from 32 V (0.91 V

per cell in open circuit) to 21 V (0.6 V per cell at maximum

load). The applicable altitude and temperature range for the

stack is shown in Fig. 14, where the red inner envelope (in the

web version) represents the operating conditions for the fuel

cell rated performance, while the yellow outer envelope (in

the web version) represents the operating conditions for

limited fuel cell performance. Operating altitude affects per-

formance since there is less oxidant for the electrochemical

reactor, leading to lower single cells voltage. A slight drop in

performance (power output) is expected typically at

1000 m ASL. One other factor affecting performance is the

ambient temperature. Higher temperature leads to drying the

PEM membrane inside the stack, reducing its conductivity

and, consequently, the power output of the fuel cell stack. Low

temperatures are counteracted using two methods. The first

Fig. 13 e 200 We fuel cell.

Fig. 14 e Applicable altitude (ASL) and temperature range

for the 200 We open cathode stack [28].

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f h y d r o g e n e n e r g y x x x ( 2 0 1 7 ) 1 e1 5 7

Please cite this article in press as: Lape~

na-Rey N, et al., A fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle for low altitude surveillance

missions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.137](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-230206105836-a236b105/85/j-ijhydene-2017-01-137-pdf-7-320.jpg)

![one consists on reducing the throttle of the fans at the back of

the stack, effectively reducing the cold air pulling heat from

the cells. The second one consists on increasing the duration

of the conditioning short-circuits [25,26] of the stack, resulting

in the stack self-heating.

Hydrogen generator

The 900 Wh hydrogen generator from Horizon Energy Systems

produces hydrogen on demand, i.e., it produces the amount of

hydrogen that the fuel cell demands, which obviously de-

pends on the fuel cell power output.

The gaseous hydrogen for the fuel cell is obtained at the

right purity (99.99%) and at fuel cell operating pressure

(0.5e0.7 barg) from 1 L of a 20% wt. sodium borohydride

(NaBH4) solution in water via a catalyzed hydrolysis reaction:

NaBH4 þ 2H2O / 4H2 þ NaBO2

The reaction takes place inside a reactor packed with the

catalyst when reaching 70

C. An intake pump feeds the fuel

from the fuel tanks into the reactor. Both the generated

gaseous hydrogen and the byproduct (sodium metaborate

NaBO2) are cooled down through a cooling coil before flowing

into a separator where light highly pure gaseous hydrogen

stays on top and the heavier byproduct stays at the bottom.

The hydrogen is then extracted through a filter/desiccator and

a pressure regulator that reduces the pressure from the 5 barg

in the reactor to the fuel cell operating pressure (0.5 barg)

before feeding the stack. The unreacted NaBH4 is forced again

towards the reactor to try to extract more hydrogen. The

byproduct is recirculated from the separator towards the

reactor where it exhausts the system through a purging valve

towards a tube which is ducted out of the aircraft. The

movement of the byproduct through the pipes in the system

poses the first challenge, operation at low ambient tempera-

tures, since the salt might precipitate in the tubes blocking the

system [24]. The purging procedure is controlled by the

hydrogen generator controller board that also informs the

stack of the relevant parameters such as the reactor's pres-

sure, and sends other data through the stack board to the user

(reactor's temperatures, sensor levels, etc.).

Exhausting the byproduct off the aircraft during flight al-

lows reducing weight progressively over the course of a flight.

Although this could theoretically be an advantage it poses the

second challenge, since the weight-shift and lose would

disrupt the aircraft center of gravity during the flight, which

might negatively affect the aircraft stability if the center of

gravity is shifted out of the its acceptable limits. This is thor-

oughly discussed in section 7.

Fig. 15 shows the fuel consumption rate at different power

outputs and ambient temperatures provided by the manu-

facturer. At ~200 W (which would constitute the worse-case

scenario for the UAV cruise power consumption, even in the

worst ambient temperature conditions (40

C)) the fuel con-

sumption was always less than 250 g/h. Therefore, 1 kg of fuel

could lead up to minimum 4 h flights and up to 5 h flights at a

200 W continuous power draw. In practice, the power draw

will vary during flight, even during cruise.

Stack and hydrogen generator bench endurance

test

Prior to mounting the system onboard, the fuel cell was

thoroughly conditioned for several days with compressed

hydrogen gas until the power output was 200 We at 24.5 V (i.e.,

~0.7 V/cell). Once fully conditioned, the fuel cell was tested

with the hydrogen generator on the bench connected to an

electronic programmable load, which simulated the electric

motor, to prove the 900 Wh of energy stated by the manu-

facturer. 1 L of freshly made fuel mixture (20% wt. NaBH4 with

demineralized water) was poured into the fuel tank. After-

wards, the separator was usually primed with 15 ml of dem-

ineralized water. The system was then started and ran for

4.5e5 h at 160 W set in the electronic load.

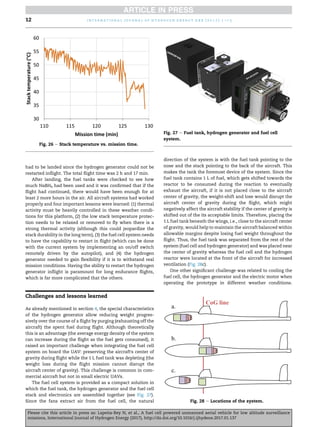

The results of a typical test are summarized in Figs. 16e18,

which show smooth and successful performance. Fig. 16

shows the total energy (Wh) delivered vs. time during the

test. The straight ascending line looks as expected. Fig. 17

shows how every 20 min the system produced ~50 Wh and

this remained fairly constant with time, and how the Wh

delivered are proportional to the fuel mass consumption, both

Fig. 15 e Fuel consumption of the hydrogen generator [23].

Fig. 16 e Total energy (Wh) vs. time e 1st run.

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f h y d r o g e n e n e r g y x x x ( 2 0 1 7 ) 1 e1 5

8

Please cite this article in press as: Lape~

na-Rey N, et al., A fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle for low altitude surveillance

missions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.137](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-230206105836-a236b105/85/j-ijhydene-2017-01-137-pdf-8-320.jpg)

![An oscilloscope logged Vbattery, Ibattery, Vload and Iload

(Fig. 20).

Fig. 21 shows the initial stages of the simulated flight

mission, and for each one, the discharge curve of the battery.

The take-off stage was the most current demanding, peaking

at 25 A from the battery. During climb simulation, the current

of the battery was mostly below 7 A and the stack was pro-

ducing the remaining 8 A. In this stage, the battery current

discharge was ~100 mV/min (Fig. 22).

After the recovery from climb, in the cruise stage, the

battery discharge stabilized and the slope suggested that the

discharge rate was below 200 mV/h (Fig. 23), which is slow

compared to the one during the climb stage (100 mV/min).

Although most of the power delivered to the load was gener-

ated by the fuel cell stack, the battery still needed to deliver

current:

To power the electronics of the controller board of the

stack.

To power the load while the self-heating short-circuits of

the stack occurred. These short-circuits keep the stack

conditioned [25,26] and happen in its normal operation

every 10 s and correspond to the negative spikes seen

throughout the test.

Drawing a conservative trend line, during 4 h of cruise the

voltage would drop only 0.8 V, i.e., from 24.5 to 23.7 V, which is

Fig. 20 e Stack and battery discharge test setup.

Fig. 21 e Battery and stack test: battery initial discharge.

Fig. 22 e Battery and stack test: climb battery discharge.

Fig. 23 e Battery and stack test: cruise battery discharge.

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f h y d r o g e n e n e r g y x x x ( 2 0 1 7 ) 1 e1 5

10

Please cite this article in press as: Lape~

na-Rey N, et al., A fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle for low altitude surveillance

missions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.137](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-230206105836-a236b105/85/j-ijhydene-2017-01-137-pdf-10-320.jpg)

![Summarizing, the system works properly if a quality con-

trol is implemented but it is complex and requires rigorous

and tedious maintenance. The hydrogen generator is sold as a

swappable system and the required maintenance is done by

the manufacturer. However, that was not found to be practical

for field operation on the other side of the world. Therefore,

the technology must mature to be successfully implemented

in UAVs that aim to be products rather than prototypes.

However, it is theoretically a practical system in which pure

hydrogen is only produced in demand and at low pressure,

which is an incredible advantage that would greatly make

certification easier than with compressed hydrogen gas, for

example. It is also ideal for operation in remote areas, to avoid

mission disruption due to fuel logistics/high cost.

Other competing technologies include the hydrolysis of

NaBH4 but at higher temperature or using for example a water

based HCl or other acidic solution as an agent. Both of these

approaches are simpler, require considerably lower mainte-

nance and use fuel that does not get out of date. One other

interesting option is exploring new chemistries (such as

MgH2), which does not require a catalyst either, is a simpler

system, requires considerably lower maintenance and might

also resolve some of the practical challenges of the system

studied here. However, the considerably higher reaction

temperature poses a thermal management challenge. Finally,

the hydrolysis of alkaline metals (Na or Li) in inert atmo-

spheres seems also a feasible and very promising technology

to be studied. Within the hydrogen storage methods, both

compressed hydrogen and liquid hydrogen should be explored

although they require considerable fuel logistics and might be

less practical for operation in remote areas.

Conclusion

BRT-Europe has corroborated that fuel cell powered electric

UAV low altitude flight missions using off-the-shelf fuel cell

technology and chemical hydrides as a hydrogen source are

feasible.

The fuel cell system chosen was found to be one of the

most lightweight and compact commercially available sys-

tems for this power range. Despite the required maintenance,

the fuel cell system proved to be very reliable although chal-

lenges were encountered when operating in hot weather

conditions, especially with strong thermal activity. The

chemical hydride technology is very promising and once it

reaches the correct readiness level, it could allow having long

endurance electric UAVs without having to store high pres-

sure gaseous hydrogen or liquid hydrogen onboard, which

would be particularly useful for operating at remote locations

or for portable applications since it would simplify the ground

logistics and workflow. This prototype was designed for op-

timum aerodynamics (glider with an L/D ~20) and the flight

tests were all smooth in terms of maneuvering to maximize

endurance. In addition, as it is only a demonstrator, the

aircraft had no payload. These are ideal conditions, which are

not representative of most UAVs that normally have more

restrictive conditions. The ceiling set for this prototype was

~1000 m AGL whereas surveillance UAVs fly up to ~5000 m or

more. The atmospheric conditions at such altitudes are totally

different with much lower pressures and temperatures, and

thus, the fuel cell system design has to be adapted for such

conditions.

r e f e r e n c e s

[1] Unmanned Systems North America 2012. Protonex

announces commercial fuel cell power system for

unmanned applications at AUVSI's unmanned systems

North America 2012. August 2012.

[2] Verstraete D, Harvey JR, Palmer JL. Hardware-in-the-loop

simulation of fuel cell-based hybrid electrical UAV

propulsion. 28th International Congress of Aeronautical

Sciences. September 2012.

[3] Lape~

na-Rey N, Mosquera J, Bataller E, Orti F, Dudfield C,

Orsillo A. Environmentally friendly power sources for

aerospace applications. J Power Sources 2008;181:353e62.

[4] Reitz TL. AFRL/RZ fuel cell program. Propulsion Directorate,

Air Force Research Laboratory. 2010.

[5] Gertler J. US unmanned aerial systems. Congressional

Research Service, Report 7e5700 prepared for Members and

Committees of US Congress. January 2012.

[6] Global Observer from AeroVironment: http://www.avinc.

com/ADC_Project_Details.asp?Prodid¼35.

[7] Fuel Cell UAV from Georgia Institute of Technology: http://

gtresearchnews.gatech.edu/newsrelease/fuel-cell-aircraft.htm.

[8] SpiderLion from Navy Research Labs and Protonex: http://

www.designation-systems.net/dusrm/app4/spider-lion.

html.

[9] HYFISH from Deutsche Raum und Luftfahrt (DLR), Smartfish

and Horizon Energy Systems: http://www.militaryaero

space.com/articles/print/volume-18/issue-6/news/hydro

gen-fuel-cell-technology-takes-off-powering-hyfish-uav.

html.

[10] SAE Pterosoar from California State University, Oklahoma

State University, Horizon Energy systems: http://www.

worldrecordacademy.com/technology/longest_micro_UAV_

flight_world_record_set_by_Pterosoar_70905.htm.

[11] Puma from AeroVironment: http://www.avinc.com/uas/adc/

fuel_cell_puma/.

[12] Endurance from SolarBubbles: http://gas2.org/2008/11/23/

michigan-students-set-world-record-for-longest-flight-by-

fuel-cell-powered-plane/.

[13] Boomerang from BlueBird Aerosystems and Horizon Energy

Systems: http://www.bluebird-uav.com/Boomerang.html.

[14] http://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/bluebird-unveils-

10h-endurance-wanderb-394566/.

[15] Ion tiger: http://www.nrl.navy.mil/media/news-releases/

2013/nrl-shatters-endurance-record-for-small-electric-uav.

[16] Rocheleau R, Virji M, Bethune K. Fuel cell stack testing and

durability in support of ion tiger UAV e final technical report.

Hawai Natural Energy Institute; June 2010.

[17] http://www.fuelcelltoday.com/news-events/news-archive/

2013/february/energyor-conducts-first-fuel-cell-uav-flights-

in-india.

[18] http://diydrones.com/profiles/blogs/hydrogen-fuel-cell-uav.

[19] http://www.suasnews.com/2012/08/18346/.

[20] http://www.engadget.com/2007/10/17/korean-researchers-

build-a-fuel-cell-uav-that-runs-for-10-hours/.

[21] http://www.insitu.com/press/hydrogen-powered-fuel-cell-

flies-scaneagle.

[22] Kordesch K, Simander J. Fuel cells and their applications.

VCH; 1996.

[23] Larminie J, Dicks A. Fuel cell systems explained. Wiley; 1999.

[24] Okumus E, San FGB, Okur O, Turk BE, Cengelci E, Kilic M,

et al. Development of boron-based hydrogen and fuel cell

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f h y d r o g e n e n e r g y x x x ( 2 0 1 7 ) 1 e1 5

14

Please cite this article in press as: Lape~

na-Rey N, et al., A fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle for low altitude surveillance

missions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.137](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-230206105836-a236b105/85/j-ijhydene-2017-01-137-pdf-14-320.jpg)

![system for small unmanned aerial vehicle. Int J Hydrogen

Energy 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.09.009.

September Edition.

[25] Gupta G, Wu B, Mylius S, Offer G. A systematic study on the

use of short circuiting for the improvement of proton

exchange membrane fuel cell performance. Int J Hydrogen

Energy 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.10.080.

November Edition.

[26] Kim J, Kim D, Kim S, Nam S, Kim T. Humidification of

polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell using short circuit

control for unmanned aerial vehicle applications. Int J

Hydrogen Energy 15 May 2014;39(15):7925e30.

[27] Horizon Energy Systems, HES: http://www.hes.sg.

[28] Aeropak technical datasheet (http://resources.arcolaenergy.

com/docs/TechnicalDataSheets/).

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f h y d r o g e n e n e r g y x x x ( 2 0 1 7 ) 1 e1 5 15

Please cite this article in press as: Lape~

na-Rey N, et al., A fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicle for low altitude surveillance

missions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.137](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-230206105836-a236b105/85/j-ijhydene-2017-01-137-pdf-15-320.jpg)