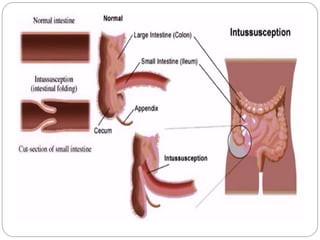

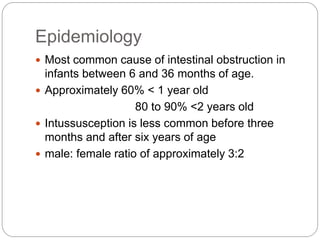

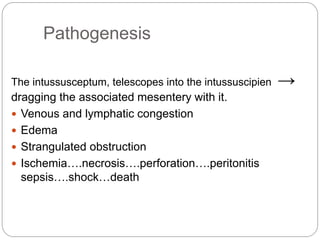

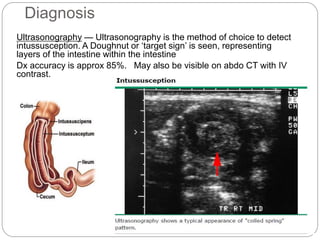

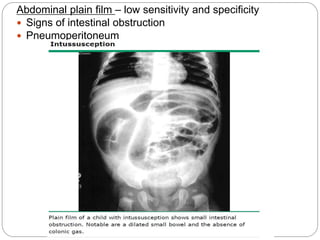

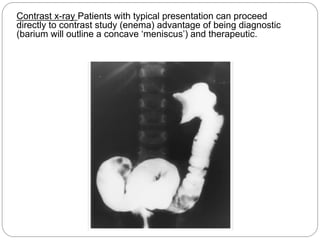

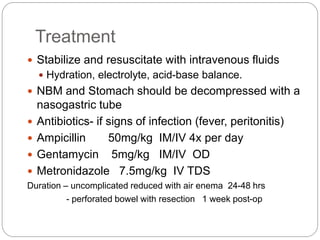

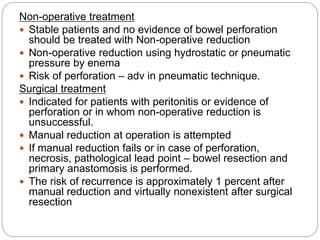

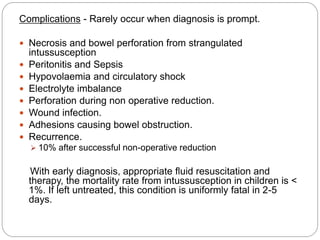

Intussusception is the telescoping of one part of the intestine into another part and is most common in children under 2 years old. The classic presentation includes intermittent abdominal pain, a sausage-shaped abdominal mass, and currant jelly stools. Ultrasound is the preferred diagnostic method and shows a target or "doughnut" sign. Treatment involves rehydration and antibiotics if infected. Non-operative reduction using hydrostatic or pneumatic pressure is usually attempted first but surgery may be needed if reduction fails or there are signs of perforation or necrosis. With prompt diagnosis and treatment, mortality from intussusception is less than 1%.