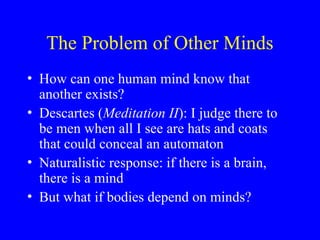

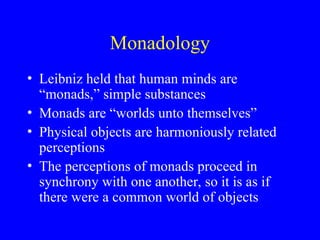

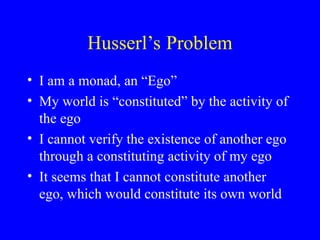

The document explores the philosophical problem of how one mind can know another exists, contrasting different theories such as Descartes' view and Leibniz's monads. It emphasizes the need for a phenomenological approach, focusing on the synthesizing activities of the ego and the concept of empathy to establish intersubjectivity. Ultimately, it argues for an inter-subjective world where multiple egos can harmoniously constitute their realities as objects of experience.