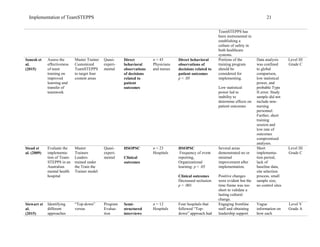

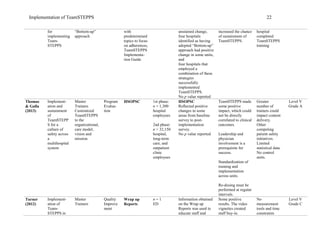

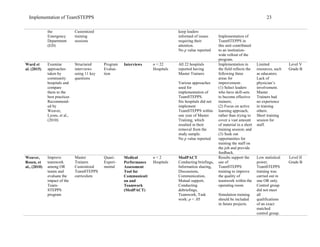

The document summarizes a literature review on the implementation of TeamSTEPPS (Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety), a team training program developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Department of Defense, in acute care hospital settings. The review identified 12 studies that evaluated different approaches to implementing TeamSTEPPS, including implementation in specific hospital units or teams, across healthcare systems, and in simulation settings. The studies used a variety of measurement tools and outcomes and most provided low-quality evidence. Overall, the review found varying results from TeamSTEPPS implementation but difficulties linking implementation directly to outcomes due to limitations in study design and measurement.

![TEAMSTEPPS IN ACUTE CARE 3

Implementation of TeamSTEPPS

In 1999, The Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a report titled To Err is Human,

estimating that, in the US, 44,000 to 98,000 annual patient deaths are related to care received in a

hospital setting. The report identified communication and system factors as leading causes of

errors, rather than the weaknesses of individuals. One of the five principles in the IOM report

focused on the effectiveness of teamwork. To improve teamwork, hospitals have been utilizing

Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) since

2006, which is a free government-sponsored program. The purpose of this literature review is to

explore TeamSTEPPS implementation in the acute care settings.

Background

TeamSTEPPS

The Agency for Healthcare Quality of Research (AHRQ) and the Department of Defense

(DoD) worked collaboratively to develop the TeamSTEPPS program. Using 30 years of

research experience obtained in the military, aviation, and healthcare industries, the AHRQ and

DoD developed materials pertaining to team leadership, situation monitoring, mutual support,

and communications aimed at improving team training initiatives and outcomes (Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality & Department of Defense [AHRQ & DoD], 2014). In 2005,

the TeamSTEPPS curriculum was field tested with 5,000 trained participants in 19 DoD

hospitals and clinics. In 2006, AHRQ expanded TeamSTEPPS into the public arena, resulting in

launching of the National Implementation Program in 2007. It was during this time that Master

Trainer Courses were developed and offered at regional training centers across the nation. In

2014, the TeamSTEPPS 2.0 Training Curriculum was released with a higher level of attention

given to simulation during the implementation process (AHRQ & DoD, 2014).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/f68811d7-ee3a-42d2-b05f-7b5143b43d78-161208130054/85/Implementation-of-TeamSTEPPS-in-Acute-Care-Settings-4-320.jpg)

![TEAMSTEPPS IN ACUTE CARE 16

Sheppard, F., Williams, M., & Klein, V. (2013). TeamSTEPPS and patient safety in healthcare.

American Society for Healthcare Risk Management of the American Hospital

Association, 32(3), 5-10. doi:10.1002/jhrm.21099

Sonesh, S. C., Gregory, M. E., Hughes, A. M., Feitosa, J., Benishek, L. E., & Verhoeven, D.

(2015). Team training in obstetrics: A multi-level evaluation. Family Systems & Health,

33(3), 250-261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000148

Stead, K., Kumar, S., Schultz, T. J., Tiver, S., Pirone, C. J., Adams, R. A., & Wareham, C. A.

(2009). Team communicating through STEPPS [Supplement]. Med J Australia, 190(11),

S128-S132.

Stewart, G. L., Manges, K. A., & Ward, M. M. (2015). Empowering sustained patient safety. The

benefits of combining top-down and bottom up approaches. Journal of Nursing Care

Quality, 30(3), 240-246. doi:10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000103

Thomas, L., & Galla, C. (2013). Building a culture of safety through team training and

engagement. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 22, 425-434. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-

001011

Turner, P. (2012). Implementation of TeamSTEPPS in the emergency department. Critical Care

Nursing, 35(3), 208-212. doi:10.1097/CNQ.0b013e3182542c6c

Ward, M. M., Zhu, X., Lampman, M., & Stewart, G. L. (2014). TeamSTEPPS implementation in

community hospitals. Adherence to recommended training approaches. International

Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 28(3), 234-244. doi:10.1108IJHCQA-

10.2013-0124](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/f68811d7-ee3a-42d2-b05f-7b5143b43d78-161208130054/85/Implementation-of-TeamSTEPPS-in-Acute-Care-Settings-17-320.jpg)