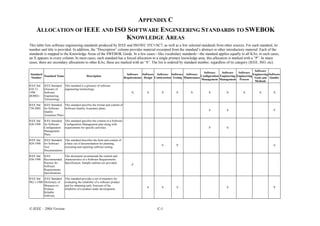

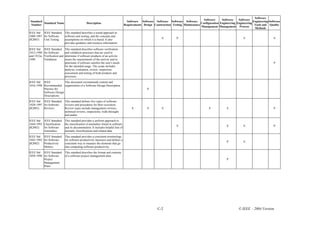

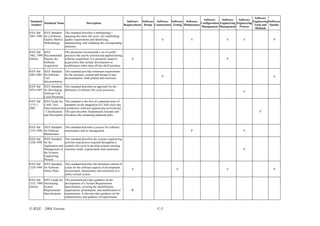

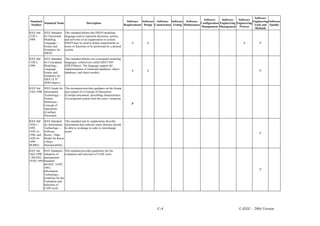

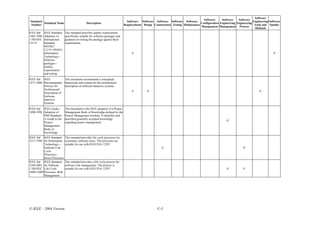

The document provides information on the 2004 version of the Guide to the Software Engineering Body of Knowledge (SWEBOK), which was created by the IEEE Computer Society as a compendium and guide to the body of knowledge for the field of software engineering. It lists the executive editors, editors, project champion, and committees involved in developing the SWEBOK guide and provides the table of contents for the guide, which covers 12 knowledge areas of software engineering.

![limitations imposed on the choice of references (see involving substantial non-software components, as many

above). A matrix links the topics to the reference material. as three different types of documents are produced:

The last part of the KA description is the list of system definition, system requirements specification, and

recommended references. Appendix A of each KA software requirements specification. The sub-area

includes suggestions for further reading for those users describes all three documents and the underlying

who wish to learn more about the KA topics. Appendix B activities.

presents the list of standards most relevant to the KA. The sixth sub-area is requirements validation, the aim of

Note that citations enclosed in square brackets “[ ]” in the which is to pick up any problems before resources are

text identify recommended references, while those committed to addressing the requirements. Requirements

enclosed in parentheses “( )” identify the usual references validation is concerned with the process of examining the

used to write or justify the text. The former are to be requirements documents to ensure that they are defining

found in the corresponding section of the KA and the the right system (that is, the system that the user expects).

latter in Appendix A of the KA. It is subdivided into descriptions of the conduct of

Brief summaries of the KA descriptions and Appendices requirements reviews, prototyping, and model validation

are given next. and acceptance tests.

The seventh and last sub-area is practical considerations.

Software Requirements KA (see Figure 2, column a) It describes topics which need to be understood in

practice. The first topic is the iterative nature of the

A requirement is defined as a property that must be requirements process. The next three topics are

exhibited in order to solve some real-world problem. fundamentally about change management and the

The first knowledge sub-area is software requirements maintenance of the requirements in a state which

fundamentals. It includes definitions of software accurately mirrors the software to be built, or that has

requirements themselves, but also of the major types of already been built. It includes change management,

requirements: product vs. process, functional vs. non- requirements attributes, and requirements tracing. The

functional, emergent properties. The sub-area also final topic is requirements measurement.

describes the importance of quantifiable requirements and

distinguishes between systems and software requirements. Software Design KA (see Figure 2, column b)

The second knowledge sub-area is the requirements According to the IEEE definition [IEEE610.12-90],

process, which introduces the process itself, orienting the design is both “the process of defining the architecture,

remaining five sub-areas and showing how requirements components, interfaces, and other characteristics of a

engineering dovetails with the other software engineering system or component” and “the result of [that] process.”

processes. It describes process models, process actors, The KA is divided into six sub-areas.

process support and management, and process quality and

improvement. The first sub-area presents the software design

fundamentals, which form an underlying basis to the

The third sub-area is requirements elicitation, which is understanding of the role and scope of software design.

concerned with where software requirements come from These are general software concepts, the context of

and how the software engineer can collect them. It software design, the software design process, and the

includes requirement sources and elicitation techniques. enabling techniques for software design.

The fourth sub-area, requirements analysis, is concerned

The second sub-area groups together the key issues in

with the process of analyzing requirements to:

software design. They include concurrency, control and

detect and resolve conflicts between requirements handling of events, distribution of components, error and

discover the bounds of the software and how it must exception handling and fault tolerance, interaction and

interact with its environment presentation, and data persistence.

elaborate system requirements to software The third sub-area is software structure and architecture,

requirements the topics of which are architectural structures and

Requirements analysis includes requirements viewpoints, architectural styles, design patterns, and,

classification, conceptual modeling, architectural design finally, families of programs and frameworks.

and requirements allocation, and requirements The fourth sub-area describes software design quality

negotiation. analysis and evaluation. While there is a entire KA

The fifth sub-area is requirements specification. devoted to software quality, this sub-area presents the

Requirements specification typically refers to the topics specifically related to software design. These

production of a document, or its electronic equivalent, aspects are quality attributes, quality analysis, and

that can be systematically reviewed, evaluated, and evaluation techniques and measures.

approved. For complex systems, particularly those The fifth sub-area is software design notations, which are

1–4 © IEEE – 2004 Version](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-28-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2

SOFTWARE REQUIREMENTS

breakdown reflects the fact that the requirements process,

ACRONYMS if it is to be successful, must be considered as a process

DAG Directed Acyclic Graph involving complex, tightly coupled activities (both se-

FSM Functional Size Measurement quential and concurrent), rather than as a discrete, one-off

INCOSE International Council on Systems Engi- activity performed at the outset of a software development

neering project.

SADT Structured Analysis and Design Tech- The Software Requirements KA is related closely to the

nique Software Design, Software Testing, Software Mainte-

UML Unified Modeling Language nance, Software Configuration Management, Software

INTRODUCTION Engineering Management, Software Engineering Process,

and Software Quality KAs.

The Software Requirements Knowledge Area (KA) is

concerned with the elicitation, analysis, specification, and

validation of software requirements. It is widely acknowl-

BREAKDOWN OF TOPICS FOR SOFTWARE

edged within the software industry that software engineer- REQUIREMENTS

ing projects are critically vulnerable when these activities 1. Software Requirements Fundamentals

are performed poorly.

1.1. Definition of a Software Requirement

Software requirements express the needs and constraints At its most basic, a software requirement is a property

placed on a software product that contribute to the solu- which must be exhibited in order to solve some problem

tion of some real-world problem. [Kot00] in the real world. The Guide refers to requirements on

The term ‘requirements engineering’ is widely used in the ‘software’ because it is concerned with problems to be

field to denote the systematic handling of requirements. addressed by software. Hence, a software requirement is a

For reasons of consistency, though, this term will not be property which must be exhibited by software developed

used in the Guide, as it has been decided that the use of or adapted to solve a particular problem. The problem

the term ‘engineering’ for activities other than software may be to automate part of a task of someone who will

engineering ones is to be avoided in this edition of the use the software, to support the business processes of the

Guide. organization that has commissioned the software, to cor-

rect shortcomings of existing software, to control a de-

For the same reason, ‘requirements engineer’, a term vice, and many more. The functioning of users, business

which appears in some of the literature, will not be used processes, and devices is typically complex. By extension,

either. Instead, the term ‘software engineer’, or, in some therefore, the requirements on particular software are

specific cases, ‘requirements specialist’ will be used, the typically a complex combination of requirements from

latter where the role in question is usually performed by different people at different levels of an organization and

an individual other than a software engineer. This does from the environment in which the software will operate.

not imply, however, that a software engineer could not

perform the function. An essential property of all software requirements is that

they be verifiable. It may be difficult or costly to verify

The KA breakdown is broadly compatible with the sec- certain software requirements. For example, verification

tions of IEEE 12207 that refer to requirements activities. of the throughput requirement on the call center may ne-

(IEEE12207.1-96) cessitate the development of simulation software. Both the

A risk inherent in the proposed breakdown is that a water- software requirements and software quality personnel

fall-like process may be inferred. To guard against this, must ensure that the requirements can be verified within

sub-area 2, Requirements Process, is designed to provide the available resource constraints.

a high-level overview of the requirements process by set- Requirements have other attributes in addition to the be-

ting out the resources and constraints under which the havioral properties that they express. Common examples

process operates and which act to configure it. include a priority rating to enable trade-offs in the face of

An alternate decomposition could use a product-based finite resources and a status value to enable project pro-

structure (system requirements, software requirements, gress to be monitored. Typically, software requirements

prototypes, use cases, and so on). The process-based are uniquely identified so that they can be subjected to

© IEEE – 2004 Version 2-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-35-320.jpg)

![software configuration control and managed over the en- shall be written in Ada.’). These are sometimes known as

tire software life cycle. [Kot00; Pfl01; Som05; Tha97] process requirements.

1.2. Product and Process Requirements Some software requirements generate implicit process

A distinction can be drawn between product parameters requirements. The choice of verification technique is one

and process parameters. Product parameters are require- example. Another might be the use of particularly rigor-

ments on software to be developed (for example, ‘The ous analysis techniques (such as formal specification

software shall verify that a student meets all prerequisites methods) to reduce faults which can lead to inadequate

before he or she registers for a course.’). reliability. Process requirements may also be imposed

directly by the development organization, their customer,

A process parameter is essentially a constraint on the de- or a third party such as a safety regulator [Kot00; Som97].

velopment of the software (for example, ‘The software

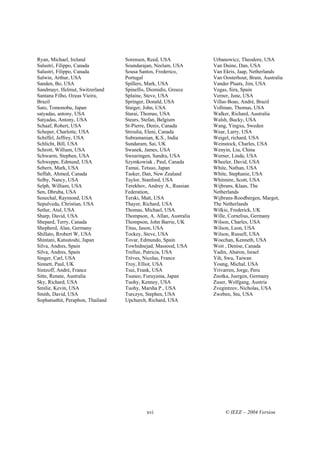

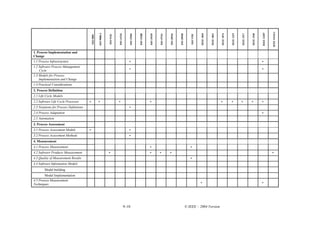

Software

Requirements

Software

Requirements Requirements Requirements Requirements Requirements Practical

Requirements

Process Elicitation Analysis Specification Validation Considerations

Fundamentals

Definition of a System Iterative Nature

Requirements Requirements Requirements

Software Process Models Definition of Requirements

Sources Classification Reviews

Requirement Document Process

Product and Systems

Elicitation Conceptual Change

Process Process Actors Requirements Prototyping

Techniques Modeling Management

Requirements Specification

Architectural

Functional and Software

Process Support Design and Model Requirements

Non-functional Requirements

and Management Requirements Validation Attributes

Requirements Specification

Allocation

Emergent Process Quality Requirements Acceptance Requirements

Properties and Improvement Negotiation Tests Tracing

Quantifiable Measuring

Requirements Requirements

System

Requirements

and Software

Requirements

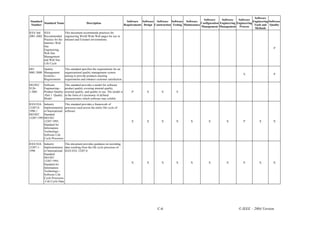

Figure 1 Breakdown of topics for the Software Requirements KA

1.3. Functional and Non-functional Requirements performance requirements, maintainability requirements,

Functional requirements describe the functions that the safety requirements, reliability requirements, or one of

software is to execute; for example, formatting some text many other types of software requirements. These topics

or modulating a signal. They are sometimes known as are also discussed in the Software Quality KA. [Kot00;

capabilities. Som97]

Non-functional requirements are the ones that act to con- 1.4. Emergent Properties

strain the solution. Non-functional requirements are some- Some requirements represent emergent properties of

times known as constraints or quality requirements. They software; that is, requirements which cannot be addressed

can be further classified according to whether they are by a single component, but which depend for their satis-

2-2 © IEEE – 2004 Version](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-36-320.jpg)

![faction on how all the software components interoperate. ning of a project and continuing to be refined

The throughput requirement for a call center would, for throughout the life cycle

example, depend on how the telephone system, informa- identifies software requirements as configuration

tion system, and the operators all interacted under actual items, and manages them using the same software

operating conditions. Emergent properties are crucially configuration management practices as other prod-

dependent on the system architecture. [Som05] ucts of the software life cycle processes

needs to be adapted to the organization and project

1.5. Quantifiable Requirements context

Software requirements should be stated as clearly and as In particular, the topic is concerned with how the activi-

unambiguously as possible, and, where appropriate, quan- ties of elicitation, analysis, specification, and validation

titatively. It is important to avoid vague and unverifiable are configured for different types of projects and con-

requirements which depend for their interpretation on straints. The topic also includes activities which provide

subjective judgment (‘The software shall be reliable’; input into the requirements process, such as marketing

‘The software shall be user-friendly’). This is particularly and feasibility studies. [Kot00; Rob99; Som97; Som05]

important for non-functional requirements. Two examples

of quantified requirements are the following: a call cen- 2.2. Process Actors

ter's software must increase the center’s throughput by This topic introduces the roles of the people who partici-

20%; and a system shall have a probability of generating a pate in the requirements process. This process is funda-

fatal error during any hour of operation of less than 1 * mentally interdisciplinary, and the requirements specialist

10-8. The throughput requirement is at a very high level needs to mediate between the domain of the stakeholder

and will need to be used to derive a number of detailed and that of software engineering. There are often many

requirements. The reliability requirement will tightly con- people involved besides the requirements specialist, each

strain the system architecture. [Dav93; Som05] of whom has a stake in the software. The stakeholders

will vary across projects, but always include us-

1.6. System Requirements and Software Requirements ers/operators and customers (who need not be the same).

In this topic, system means ‘an interacting combination of [Gog93]

elements to accomplish a defined objective. These include

hardware, software, firmware, people, information, tech- Typical examples of software stakeholders include (but

niques, facilities, services, and other support elements,’ as are not restricted to):

defined by the International Council on Systems Engi- Users–This group comprises those who will operate

neering (INCOSE00). the software. It is often a heterogeneous group com-

System requirements are the requirements for the system prising people with different roles and requirements.

as a whole. In a system containing software components, Customers–This group comprises those who have

software requirements are derived from system require- commissioned the software or who represent the

ments. software’s target market.

Market analysts–A mass-market product will not

The literature on requirements sometimes calls system have a commissioning customer, so marketing peo-

requirements ‘user requirements’. The Guide defines ‘user ple are often needed to establish what the market

requirements’ in a restricted way as the requirements of needs and to act as proxy customers.

the system’s customers or end-users. System require- Regulators–Many application domains such as

ments, by contrast, encompass user requirements, re- banking and public transport are regulated. Software

quirements of other stakeholders (such as regulatory au- in these domains must comply with the requirements

thorities), and requirements without an identifiable human of the regulatory authorities.

source. Software engineers–These individuals have a le-

gitimate interest in profiting from developing the

2. Requirements Process software by, for example, reusing components in

This section introduces the software requirements process, other products. If, in this scenario, a customer of a

orienting the remaining five sub-areas and showing how particular product has specific requirements which

the requirements process dovetails with the overall soft- compromise the potential for component reuse, the

ware engineering process. [Dav93; Som05] software engineers must carefully weigh their own

stake against those of the customer.

2.1. Process Models It will not be possible to perfectly satisfy the requirements

The objective of this topic is to provide an understanding of every stakeholder, and it is the software engineer’s job

that the requirements process: to negotiate trade-offs which are both acceptable to the

is not a discrete front-end activity of the software principal stakeholders and within budgetary, technical,

life cycle, but rather a process initiated at the begin- regulatory, and other constraints. A prerequisite for this is

that all the stakeholders be identified, the nature of their

© IEEE – 2004 Version 2-3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-37-320.jpg)

![‘stake’ analyzed, and their requirements elicited. [Dav93; 3.1. Requirements Sources

Kot00; Rob99; Som97; You01] [Dav93; Gog93; Pfl01]

2.3. Process Support and Management Requirements have many sources in typical software, and

This topic introduces the project management resources it is essential that all potential sources be identified and

required and consumed by the requirements process. It evaluated for their impact on it. This topic is designed to

establishes the context for the first sub-area (Initiation promote awareness of the various sources of software

and Scope Definition) of the Software Engineering Man- requirements and of the frameworks for managing them.

agement KA. Its principal purpose is to make the link The main points covered are:

between the process activities identified in 2.1 and the

Goals. The term goal (sometimes called ‘business

issues of cost, human resources, training, and tools.

concern’ or ‘critical success factor’) refers to the

[Rob99; Som97; You01]

overall, high-level objectives of the software. Goals

2.4. Process Quality and Improvement provide the motivation for the software, but are of-

This topic is concerned with the assessment of the quality ten vaguely formulated. Software engineers need to

and improvement of the requirements process. Its purpose pay particular attention to assessing the value (rela-

is to emphasize the key role the requirements process tive to priority) and cost of goals. A feasibility study

plays in terms of the cost and timeliness of a software is a relatively low-cost way of doing this. [Lou95].

product, and of the customer’s satisfaction with it Domain knowledge. The software engineer needs to

[Som97]. It will help to orient the requirements process acquire, or have available, knowledge about the ap-

with quality standards and process improvement models plication domain. This enables them to infer tacit

for software and systems. Process quality and improve- knowledge that the stakeholders do not articulate,

ment is closely related to both the Software Quality KA assess the trade-offs that will be necessary between

and the Software Engineering Process KA. Of particular conflicting requirements, and, sometimes, to act as a

interest are issues of software quality attributes and meas- ‘user’ champion.

urement, and software process definition. This topic cov- Stakeholders (see topic 2.2 Process Actors). Much

ers: software has proved unsatisfactory because it has

stressed the requirements of one group of stake-

requirements process coverage by process im- holders at the expense of those of others. Hence,

provement standards and models software is delivered which is difficult to use or

requirements process measures and benchmarking which subverts the cultural or political structures of

improvement planning and implementation [Kot00; the customer organization. The software engineer

Som97; You01] needs to identify, represent, and manage the ‘view-

3. Requirements Elicitation points’ of many different types of stakeholders.

[Kot00].

[Dav93; Gog93; Lou95; Pfl01] The operational environment. Requirements will be

Requirements elicitation is concerned with where soft- derived from the environment in which the software

ware requirements come from and how the software engi- will be executed. These may be, for example, timing

neer can collect them. It is the first stage in building an constraints in real-time software or interoperability

understanding of the problem the software is required to constraints in an office environment. These must be

solve. It is fundamentally a human activity, and is where actively sought out, because they can greatly affect

the stakeholders are identified and relationships estab- software feasibility and cost, and restrict design

lished between the development team and the customer. It choices. [Tha97]

is variously termed ‘requirements capture’, ‘requirements The organizational environment. Software is often

discovery’, and ‘requirements acquisition.’ required to support a business process, the selection

of which may be conditioned by the structure, cul-

One of the fundamental tenets of good software engineer- ture, and internal politics of the organization. The

ing is that there be good communication between software software engineer needs to be sensitive to these,

users and software engineers. Before development begins, since, in general, new software should not force un-

requirements specialists may form the conduit for this planned change on the business process.

communication. They must mediate between the domain

of the software users (and other stakeholders) and the 3.2. Elicitation Techniques

technical world of the software engineer. [Dav93; Kot00; Lou95; Pfl01]

Once the requirements sources have been identified, the

software engineer can start eliciting requirements from

them. This topic concentrates on techniques for getting

human stakeholders to articulate their requirements. It is a

very difficult area and the software engineer needs to be

2-4 © IEEE – 2004 Version](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-38-320.jpg)

![sensitized to the fact that (for example) users may have relatively expensive, but they are instructive because

difficulty describing their tasks, may leave important in- they illustrate that many user tasks and business

formation unstated, or may be unwilling or unable to co- processes are too subtle and complex for their actors

operate. It is particularly important to understand that to describe easily.

elicitation is not a passive activity, and that, even if coop-

erative and articulate stakeholders are available, the soft-

4. Requirements Analysis

ware engineer has to work hard to elicit the right informa- [Som05]

tion. A number of techniques exist for doing this, the This topic is concerned with the process of analyzing re-

principal ones being: [Gog93] quirements to:

Interviews, a ‘traditional’ means of eliciting re- detect and resolve conflicts between requirements

quirements. It is important to understand the advan- discover the bounds of the software and how it must

tages and limitations of interviews, and how they interact with its environment

should be conducted. elaborate system requirements to derive software

Scenarios, a valuable means for providing context to requirements

the elicitation of user requirements. They allow the The traditional view of requirements analysis has been

software engineer to provide a framework for ques- that it be reduced to conceptual modeling using one of a

tions about user tasks by permitting ‘what if’ and number of analysis methods such as the Structured Analy-

‘how is this done’ questions to be asked. The most sis and Design Technique (SADT). While conceptual

common type of scenario is the use case. There is a modeling is important, we include the classification of

link here to topic 4.2. (Conceptual Modeling), be- requirements to help inform trade-offs between require-

cause scenario notations such as use cases and dia- ments (requirements classification) and the process of

grams are common in modeling software. establishing these trade-offs (requirements negotiation).

Prototypes, a valuable tool for clarifying unclear [Dav93]

requirements. They can act in a similar way to sce-

narios by providing users with a context within Care must be taken to describe requirements precisely

which they can better understand what information enough to enable the requirements to be validated, their

they need to provide. There is a wide range of proto- implementation to be verified, and their costs to be esti-

typing techniques, from paper mock-ups of screen mated.

designs to beta-test versions of software products,

4.1. Requirements Classification

and a strong overlap of their use for requirements

elicitation and the use of prototypes for require- [Dav93; Kot00; Som05]

ments validation (see topic 6.2 Prototyping). Requirements can be classified on a number of dimen-

Facilitated meetings. The purpose of these is to try sions. Examples include:

to achieve a summative effect whereby a group of

people can bring more insight into their software re- Whether the requirement is functional or non-

quirements than by working individually. They can functional (see topic 1.3 Functional and Non-

brainstorm and refine ideas which may be difficult functional Requirements).

to bring to the surface using interviews. Another ad- Whether the requirement is derived from one or

vantage is that conflicting requirements surface more high-level requirements or an emergent prop-

early on in a way that lets the stakeholders recognize erty (see topic 1.4 Emergent Properties), or is being

where there is conflict. When it works well, this imposed directly on the software by a stakeholder or

technique may result in a richer and more consistent some other source.

set of requirements than might otherwise be achiev- Whether the requirement is on the product or the

able. However, meetings need to be handled care- process. Requirements on the process can constrain

fully (hence the need for a facilitator) to prevent a the choice of contractor, the software engineering

situation from occurring where the critical abilities process to be adopted, or the standards to be adhered

of the team are eroded by group loyalty, or the re- to.

quirements reflecting the concerns of a few outspo- The requirement priority. In general, the higher the

ken (and perhaps senior) people are favored to the priority, the more essential the requirement is for

detriment of others. meeting the overall goals of the software. Often

Observation. The importance of software context classified on a fixed-point scale such as mandatory,

within the organizational environment has led to the highly desirable, desirable, or optional, the priority

adaptation of observational techniques for require- often has to be balanced against the cost of devel-

ments elicitation. Software engineers learn about opment and implementation.

user tasks by immersing themselves in the environ- The scope of the requirement. Scope refers to the

ment and observing how users interact with their extent to which a requirement affects the software

software and with each other. These techniques are and software components. Some requirements, par-

© IEEE – 2004 Version 2-5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-39-320.jpg)

![ticularly certain non-functional ones, have a global The process requirements of the customer. Custom-

scope in that their satisfaction cannot be allocated to ers may impose their favored notation or method, or

a discrete component. Hence, a requirement with prohibit any with which they are unfamiliar. This

global scope may strongly affect the software archi- factor can conflict with the previous factor.

tecture and the design of many components, The availability of methods and tools. Notations or

whereas one with a narrow scope may offer a num- methods which are poorly supported by training and

ber of design choices and have little impact on the tools may not achieve widespread acceptance even if

satisfaction of other requirements. they are suited to particular types of problems.

Volatility/stability. Some requirements will change Note that, in almost all cases, it is useful to start by build-

during the life cycle of the software, and even dur- ing a model of the software context. The software context

ing the development process itself. It is useful if provides a connection between the intended software and

some estimate of the likelihood that a requirement its external environment. This is crucial to understanding

change can be made. For example, in a banking ap- the software’s context in its operational environment and

plication, requirements for functions to calculate and to identifying its interfaces with the environment.

credit interest to customers’ accounts are likely to be

more stable than a requirement to support a particu- The issue of modeling is tightly coupled with that of

lar kind of tax-free account. The former reflect a methods. For practical purposes, a method is a notation

fundamental feature of the banking domain (that ac- (or set of notations) supported by a process which guides

counts can earn interest), while the latter may be the application of the notations. There is little empirical

rendered obsolete by a change to government legis- evidence to support claims for the superiority of one nota-

lation. Flagging potentially volatile requirements tion over another. However, the widespread acceptance of

can help the software engineer establish a design a particular method or notation can lead to beneficial in-

which is more tolerant of change. dustry-wide pooling of skills and knowledge. This is cur-

rently the situation with the UML (Unified Modeling

Other classifications may be appropriate, depending upon

Language). (UML04)

the organization’s normal practice and the application

itself. Formal modeling using notations based on discrete

mathematics, and which are traceable to logical reasoning,

There is a strong overlap between requirements classifica-

have made an impact in some specialized domains. These

tion and requirements attributes (see topic 7.3 Require-

may be imposed by customers or standards, or may offer

ments Attributes).

compelling advantages to the analysis of certain critical

4.2. Conceptual Modeling functions or components.

[Dav93; Kot00; Som05] This topic does not seek to ‘teach’ a particular modeling

The development of models of a real-world problem is style or notation, but rather provides guidance on the pur-

key to software requirements analysis. Their purpose is to pose and intent of modeling.

aid in understanding the problem, rather than to initiate Two standards provide notations which may be useful in

design of the solution. Hence, conceptual models com- performing conceptual modeling–IEEE Std 1320.1,

prise models of entities from the problem domain config- IDEF0 for functional modeling; and IEEE Std 1320.2,

ured to reflect their real-world relationships and depend- IDEF1X97 (IDEFObject) for information modeling.

encies.

4.3. Architectural Design and Requirements Allocation

Several kinds of models can be developed. These include

[Dav93; Som05]

data and control flows, state models, event traces, user

interactions, object models, data models, and many others. At some point, the architecture of the solution must be

The factors that influence the choice of model include: derived. Architectural design is the point at which the

requirements process overlaps with software or systems

The nature of the problem. Some types of software

design, and illustrates how impossible it is to cleanly de-

demand that certain aspects be analyzed particularly

couple the two tasks. [Som01] This topic is closely re-

rigorously. For example, control flow and state

lated to the Software Structure and Architecture sub-area

models are likely to be more important for real-time

in the Software Design KA. In many cases, the software

software than for management information software,

engineer acts as software architect because the process of

while it would usually be the opposite for data mod-

analyzing and elaborating the requirements demands that

els.

the components that will be responsible for satisfying the

The expertise of the software engineer. It is often

requirements be identified. This is requirements alloca-

more productive to adopt a modeling notation or

tion–the assignment, to components, of the responsibility

method with which the software engineer has ex-

for satisfying requirements.

perience.

2-6 © IEEE – 2004 Version](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-40-320.jpg)

![Allocation is important to permit detailed analysis of re- among the large number of requirements. So, in software

quirements. Hence, for example, once a set of require- engineering jargon, ‘software requirements specification’

ments has been allocated to a component, the individual typically refers to the production of a document, or its

requirements can be further analyzed to discover further electronic equivalent, which can be systematically re-

requirements on how the component needs to interact viewed, evaluated, and approved. For complex systems,

with other components in order to satisfy the allocated particularly those involving substantial non-software

requirements. In large projects, allocation stimulates a components, as many as three different types of docu-

new round of analysis for each subsystem. As an example, ments are produced: system definition, system require-

requirements for a particular braking performance for a ments, and software requirements. For simple software

car (braking distance, safety in poor driving conditions, products, only the third of these is required. All three

smoothness of application, pedal pressure required, and so documents are described here, with the understanding that

on) may be allocated to the braking hardware (mechanical they may be combined as appropriate. A description of

and hydraulic assemblies) and an anti-lock braking system systems engineering can be found in Chapter 12, Related

(ABS). Only when a requirement for an anti-lock braking Disciplines of Software Engineering.

system has been identified, and the requirements allocated

to it, can the capabilities of the ABS, the braking hard- 5.1. The System Definition Document

ware, and emergent properties (such as the car weight) be This document (sometimes known as the user require-

used to identify the detailed ABS software requirements. ments document or concept of operations) records the

system requirements. It defines the high-level system re-

Architectural design is closely identified with conceptual quirements from the domain perspective. Its readership

modeling. The mapping from real-world domain entities includes representatives of the system users/customers

to software components is not always obvious, so archi- (marketing may play these roles for market-driven soft-

tectural design is identified as a separate topic. The re- ware), so its content must be couched in terms of the do-

quirements of notations and methods are broadly the same main. The document lists the system requirements along

for both conceptual modeling and architectural design. with background information about the overall objectives

IEEE Std 1471-2000, Recommended Practice for Archi- for the system, its target environment and a statement of

tectural Description of Software Intensive Systems, sug- the constraints, assumptions, and non-functional require-

gests a multiple-viewpoint approach to describing the ments. It may include conceptual models designed to il-

architecture of systems and their software items. lustrate the system context, usage scenarios and the prin-

(IEEE1471-00) cipal domain entities, as well as data, information, and

workflows. IEEE Std 1362, Concept of Operations

4.4. Requirements Negotiation Document, provides advice on the preparation and content

Another term commonly used for this sub-topic is ‘con- of such a document. (IEEE1362-98)

flict resolution’. This concerns resolving problems with

requirements where conflicts occur between two stake- 5.2. System Requirements Specification

holders requiring mutually incompatible features, between [Dav93; Kot00; Rob99; Tha97]

requirements and resources, or between functional and Developers of systems with substantial software and non-

non-functional requirements, for example. [Kot00, software components, a modern airliner, for example,

Som97] In most cases, it is unwise for the software engi- often separate the description of system requirements

neer to make a unilateral decision, and so it becomes nec- from the description of software requirements. In this

essary to consult with the stakeholder(s) to reach a con- view, system requirements are specified, the software

sensus on an appropriate trade-off. It is often important requirements are derived from the system requirements,

for contractual reasons that such decisions be traceable and then the requirements for the software components

back to the customer. We have classified this as a soft- are specified. Strictly speaking, system requirements

ware requirements analysis topic because problems specification is a systems engineering activity and falls

emerge as the result of analysis. However, a strong case outside the scope of this Guide. IEEE Std 1233 is a guide

can also be made for considering it a requirements valida- for developing system requirements. (IEEE1233-98)

tion topic.

5.3. Software Requirements Specification

5. Requirements Specification [Kot00; Rob99]

For most engineering professions, the term ‘specification’

refers to the assignment of numerical values or limits to a Software requirements specification establishes the basis

product’s design goals. (Vin90) Typical physical systems for agreement between customers and contractors or sup-

have a relatively small number of such values. Typical pliers (in market-driven projects, these roles may be

software has a large number of requirements, and the em- played by the marketing and development divisions) on

phasis is shared between performing the numerical quanti- what the software product is to do, as well as what it is

fication and managing the complexity of interaction not expected to do. For non-technical readers, the soft-

ware requirements specification document is often ac-

© IEEE – 2004 Version 2-7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-41-320.jpg)

![companied by a software requirements definition docu- review the document(s). Requirements documents are

ment. subject to the same software configuration management

practices as the other deliverables of the software life cy-

Software requirements specification permits a rigorous

cle processes. (Bry94, Ros98)

assessment of requirements before design can begin and

reduces later redesign. It should also provide a realistic It is normal to explicitly schedule one or more points in

basis for estimating product costs, risks, and schedules. the requirements process where the requirements are vali-

dated. The aim is to pick up any problems before re-

Organizations can also use a software requirements speci-

sources are committed to addressing the requirements.

fication document to develop their own validation and

Requirements validation is concerned with the process of

verification plans more productively.

examining the requirements document to ensure that it

Software requirements specification provides an informed defines the right software (that is, the software that the

basis for transferring a software product to new users or users expect). [Kot00]

new machines. Finally, it can provide a basis for software

enhancement. 6.1. Requirements Reviews

[Kot00; Som05; Tha97]

Software requirements are often written in natural lan-

guage, but, in software requirements specification, this Perhaps the most common means of validation is by in-

may be supplemented by formal or semi-formal descrip- spection or reviews of the requirements document(s). A

tions. Selection of appropriate notations permits particular group of reviewers is assigned a brief to look for errors,

requirements and aspects of the software architecture to mistaken assumptions, lack of clarity, and deviation from

be described more precisely and concisely than natural standard practice. The composition of the group that con-

language. The general rule is that notations should be ducts the review is important (at least one representative

used which allow the requirements to be described as pre- of the customer should be included for a customer-driven

cisely as possible. This is particularly crucial for safety- project, for example), and it may help to provide guidance

critical and certain other types of dependable software. on what to look for in the form of checklists.

However, the choice of notation is often constrained by Reviews may be constituted on completion of the system

the training, skills and preferences of the document’s au- definition document, the system specification document,

thors and readers. the software requirements specification document, the

A number of quality indicators have been developed baseline specification for a new release, or at any other

which can be used to relate the quality of software re- step in the process. IEEE Std 1028 provides guidance on

quirements specification to other project variables such as conducting such reviews. (IEEE1028-97) Reviews are

cost, acceptance, performance, schedule, reproducibility, also covered in the Software Quality KA, topic 2.3 Re-

etc. Quality indicators for individual software require- views and Audits.

ments specification statements include imperatives, direc-

6.2. Prototyping

tives, weak phrases, options, and continuances. Indicators

for the entire software requirements specification docu- [Dav93; Kot00; Som05; Tha97]

ment include size, readability, specification, depth, and Prototyping is commonly a means for validating the soft-

text structure. [Dav93; Tha97] (Ros98) ware engineer's interpretation of the software require-

IEEE has a standard, IEEE Std 830 [IEEE830-98], for the ments, as well as for eliciting new requirements. As with

production and content of the software requirements elicitation, there is a range of prototyping techniques and

specification. Also, IEEE 1465 (similar to ISO/IEC a number of points in the process where prototype valida-

12119), is a standard treating quality requirements in tion may be appropriate. The advantage of prototypes is

software packages. (IEEE1465-98) that they can make it easier to interpret the software engi-

neer's assumptions and, where needed, give useful feed-

6. Requirements validation back on why they are wrong. For example, the dynamic

[Dav93] behavior of a user interface can be better understood

through an animated prototype than through textual de-

The requirements documents may be subject to validation scription or graphical models. There are also disadvan-

and verification procedures. The requirements may be tages, however. These include the danger of users’ atten-

validated to ensure that the software engineer has under- tion being distracted from the core underlying functional-

stood the requirements, and it is also important to verify ity by cosmetic issues or quality problems with the proto-

that a requirements document conforms to company stan- type. For this reason, several people recommend proto-

dards, and that it is understandable, consistent, and com- types which avoid software, such as flip-chart-based

plete. Formal notations offer the important advantage of mockups. Prototypes may be costly to develop. However,

permitting the last two properties to be proven (in a re- if they avoid the wastage of resources caused by trying to

stricted sense, at least). Different stakeholders, including satisfy erroneous requirements, their cost can be more

representatives of the customer and developer, should easily justified.

2-8 © IEEE – 2004 Version](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-42-320.jpg)

![6.3. Model Validation of, existing software where the architecture is a given. In

[Dav93; Kot00; Tha97] practice, therefore, it is almost always impractical to im-

plement the requirements process as a linear, determinis-

It is typically necessary to validate the quality of the mod- tic process in which software requirements are elicited

els developed during analysis. For example, in object from the stakeholders, baselined, allocated, and handed

models, it is useful to perform a static analysis to verify over to the software development team. It is certainly a

that communication paths exist between objects which, in myth that the requirements for large software projects are

the stakeholders’ domain, exchange data. If formal speci- ever perfectly understood or perfectly specified. [Som97]

fication notations are used, it is possible to use formal

reasoning to prove specification properties. Instead, requirements typically iterate towards a level of

quality and detail which is sufficient to permit design and

6.4. Acceptance Tests procurement decisions to be made. In some projects, this

[Dav93] may result in the requirements being baselined before all

their properties are fully understood. This risks expensive

An essential property of a software requirement is that it rework if problems emerge late in the software engineer-

should be possible to validate that the finished product ing process. However, software engineers are necessarily

satisfies it. Requirements which cannot be validated are constrained by project management plans and must there-

really just ‘wishes’. An important task is therefore plan- fore take steps to ensure that the ‘quality’ of the require-

ning how to verify each requirement. In most cases, de-

ments is as high as possible given the available resources.

signing acceptance tests does this.

They should, for example, make explicit any assumptions

Identifying and designing acceptance tests may be diffi- which underpin the requirements, as well as any known

cult for non-functional requirements (see topic 1.3 Func- problems.

tional and Non-functional Requirements). To be vali-

In almost all cases, requirements understanding continues

dated, they must first be analyzed to the point where they to evolve as design and development proceeds. This often

can be expressed quantitatively. leads to the revision of requirements late in the life cycle.

Additional information can be found in the Software Test- Perhaps the most crucial point in understanding require-

ing KA, sub-topic 2.2.4 Conformance Testing. ments engineering is that a significant proportion of the

requirements will change. This is sometimes due to errors

7. Practical Considerations in the analysis, but it is frequently an inevitable conse-

The first level of decomposition of sub-areas presented in quence of change in the ‘environment’: for example, the

this KA may seem to describe a linear sequence of activi- customer's operating or business environment, or the mar-

ties. This is a simplified view of the process. [Dav93] ket into which software must sell. Whatever the cause, it

is important to recognize the inevitability of change and

The requirements process spans the whole software life take steps to mitigate its effects. Change has to be man-

cycle. Change management and the maintenance of the aged by ensuring that proposed changes go through a de-

requirements in a state which accurately mirrors the soft- fined review and approval process, and, by applying care-

ware to be built, or that has been built, are key to the suc- ful requirements tracing, impact analysis, and software

cess of the software engineering process. [Kot00; Lou95] configuration management (see the Software Configura-

Not every organization has a culture of documenting and tion Management KA). Hence, the requirements process

managing requirements. It is frequent in dynamic start-up is not merely a front-end task in software development,

companies, driven by a strong ‘product vision’ and lim- but spans the whole software life cycle. In a typical pro-

ited resources, to view requirements documentation as an ject, the software requirements activities evolve over time

unnecessary overhead. Most often, however, as these from elicitation to change management.

companies expand, as their customer base grows, and as

7.2. Change Management

their product starts to evolve, they discover that they need

to recover the requirements that motivated product fea- [Kot00]

tures in order to assess the impact of proposed changes. Change management is central to the management of re-

Hence, requirements documentation and change manage- quirements. This topic describes the role of change man-

ment are key to the success of any requirements process. agement, the procedures that need to be in place, and the

analysis that should be applied to proposed changes. It has

7.1. Iterative nature of the Requirements Process

strong links to the Software Configuration Management

[Kot00; You01] KA.

There is general pressure in the software industry for ever

7.3. Requirements Attributes

shorter development cycles, and this is particularly pro-

nounced in highly competitive market-driven sectors. [Kot00]

Moreover, most projects are constrained in some way by Requirements should consist not only of a specification of

their environment, and many are upgrades to, or revisions what is required, but also of ancillary information which

© IEEE – 2004 Version 2-9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-43-320.jpg)

![helps manage and interpret the requirements. This should satisfy it (for example, from a system requirement into the

include the various classification dimensions of the re- software requirements that have been elaborated from it,

quirement (see topic 4.1 Requirements Classification) and and on into the code modules that implement it).

the verification method or acceptance test plan. It may

The requirements tracing for a typical project will form a

also include additional information such as a summary

complex directed acyclic graph (DAG) of requirements.

rationale for each requirement, the source of each re-

quirement, and a change history. The most important re- 7.5. Measuring Requirements

quirements attribute, however, is an identifier which al- As a practical matter, it is typically useful to have some

lows the requirements to be uniquely and unambiguously concept of the ‘volume’ of the requirements for a particu-

identified. lar software product. This number is useful in evaluating

7.4. Requirements Tracing the ‘size’ of a change in requirements, in estimating the

cost of a development or maintenance task, or simply for

[Kot00]

use as the denominator in other measurements. Functional

Requirements tracing is concerned with recovering the Size Measurement (FSM) is a technique for evaluating the

source of requirements and predicting the effects of re- size of a body of functional requirements. IEEE Std

quirements. Tracing is fundamental to performing impact 14143.1 defines the concept of FSM. [IEEE14143.1-00]

analysis when requirements change. A requirement should Standards from ISO/IEC and other sources describe par-

be traceable backwards to the requirements and stake- ticular FSM methods

holders which motivated it (from a software requirement

Additional information on size measurement and stan-

back to the system requirement(s) that it helps satisfy, for

dards will be found in the Software Engineering Process

example). Conversely, a requirement should be traceable

KA.

forwards into the requirements and design entities that

2-10 © IEEE – 2004 Version](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-44-320.jpg)

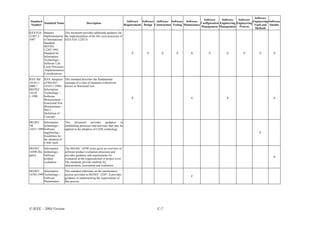

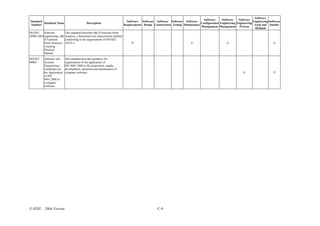

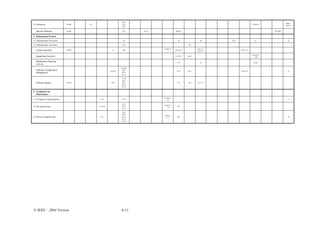

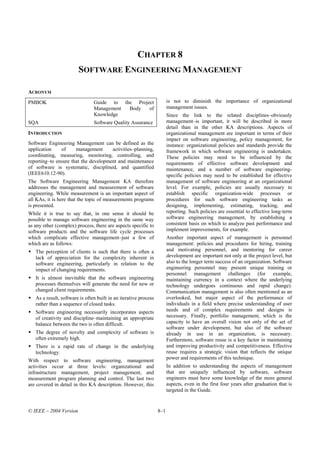

![MATRIX OF TOPICS VS. REFERENCE MATERIAL

[IEEE830

[IEEE141

[Som97]

[Som05]

[Rob99]

[You01]

[Gog93]

43.1-00]

[Tha97]

[Lou95]

[Dav93]

[Kot00]

[Pfl01]

-98]

1. Software Requirements Fundamentals

1.1 Definition of a Software Requirement * * c5 c1

1.2 Product and Process Requirements * c1

1.3 Functional and Non-functional

* c1

Requirements

1.4 Emergent Properties c2

c3s

1.5 Quantifiable Requirements c6

4

1.6 System Requirements and Software

Requirements

2. Requirements Process * c5

2.1 Process Models c2s1 * c2 c3

2.2 Process Actors c2 * c2s2 c3 c2 c3

2.3 Process Support and Management c3 c2 c2,c7

2.4 Process Quality and Improvement c2s4 c2 c5

3. Requirements Elicitation * * * *

3.1 Requirements Sources c2 * c3s1 * * c1

3.2 Elicitation Techniques c2 * c3s2 * *

4. Requirements Analysis * c6

4.1 Requirements Classification * c8s1 c6

4.2 Conceptual Modeling * * c7

4.3 Architectural Design and Requirements

* c10

Allocation

4.4 Requirements Negotiation c3s4 *

5. Requirements Specification

5.1 The System Definition Document

5.2 The System Requirements Specification * * c9 c3

5.3 The Software Requirements Specification * * * c9 c3

6. Requirements Validation * *

6.1 Requirements Reviews c4s1 c6 c5

6.2 Prototyping c6 c4s2 c8 c6

6.3 Model Validation * c4s3 c5

6.4 Acceptance Tests *

7. Practical Considerations * * *

7.1 Iterative Nature of the Requirements

c5s1 c2 c6

Process

7.2 Change Management c5s3

7.3 Requirement Attributes c5s2

7.4 Requirements Tracing c5s4

7.5 Measuring Requirements *

© IEEE – 2004 Version 2-11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-45-320.jpg)

![Sons, 2000.

RECOMMENDED REFERENCES FOR SOFTWARE [Lou95] P. Loucopulos and V. Karakostas, Systems Re-

REQUIREMENTS quirements Engineering: McGraw-Hill, 1995.

[Dav93] A. M. Davis, Software Requirements: Objects, [Pfl01] S. L. Pfleeger, "Software Engineering: Theory and

Functions and States: Prentice-Hall, 1993. Practice," Second ed: Prentice-Hall, 2001, Chap. 4.

[Gog93] J. Goguen and C. Linde, "Techniques for Re- [Rob99] S. Robertson and J. Robertson, Mastering the

quirements Elicitation," presented at International Sympo- Requirements Process: Addison-Wesley, 1999.

sium on Requirements Engineering, San Diego, Califor- [Som97] I. Sommerville and P. Sawyer, "Requirements

nia, 1993 engineering: A Good Practice Guide," John Wiley and

[IEEE830-98] IEEE Std 830-1998, IEEE Recommended Sons, 1997, Chap. 1-2.

Practice for Software Requirements Specifications: IEEE, [Som05] I. Sommerville, "Software Engineering," Sev-

1998. enth ed: Addison-Wesley, 2005.

(IEEE14143.1-00) IEEE Std 14143.1- [Tha97] R. H. Thayer and M. Dorfman, Eds., "Software

2000//ISO/IEC14143-1:1998, Information Technology- Requirements Engineering." IEEE Computer Society

Software Measurement-Functional Size Measurement- Press, 1997, 176-205, 389-404.

Part 1: Definitions of Concepts: IEEE, 2000. [You01] R. R. You, Effective Requirements Practices:

[Kot00] G. Kotonya and I. Sommerville, Requirements Addison-Wesley, 2001.

Engineering: Processes and Techniques: John Wiley and

2-12 © IEEE – 2004 Version](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-46-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 3

SOFTWARE DESIGN

Concerning the scope of the Software Design knowledge

ACRONYMS area (KA), the current KA description does not discuss

ADL Architecture Description Languages every topic the name of which contains the word “design.”

In Tom DeMarco’s terminology (DeM99), the KA dis-

CRC Collaboration Responsibilities Card

cussed in this chapter deals mainly with D-design (decom-

ERD Entity-Relationship Diagrams position design, mapping software into component pieces).

IDL Interface Description Languages However, because of its importance in the growing field of

software architecture, we will also address FP-design (fam-

DFD Data Flow Diagram

ily pattern design, whose goal is to establish exploitable

PDL Pseudo-Code and Program Design Languages commonalities in a family of software). By contrast, the

CBD Component-based design Software Design KA does not address I-design (invention

design, usually performed during the software requirements

INTRODUCTION process with the objective of conceptualizing and spe-

cifying software to satisfy discovered needs and require-

Design is defined in [IEEE610.12-90] as both “the process ments), since this topic should be considered part of requi-

of defining the architecture, components, interfaces, and rements analysis and specification.

other characteristics of a system or component” and “the

result of [that] process.” Viewed as a process, software The Software Design KA description is related specifically

design is the software engineering life cycle activity in to Software Requirements, Software Construction, Soft-

which software requirements are analyzed in order to pro- ware Engineering Management, Software Quality and Re-

duce a description of the software’s internal structure that lated Disciplines of Software Engineering.

will serve as the basis for its construction. More precisely, a

software design (the result) must describe the software

BREAKDOWN OF TOPICS FOR SOFTWARE

architecture—that is, how software is decomposed and DESIGN

organized into components—and the interfaces between 1. Software Design Fundamentals

those components. It must also describe the components at

a level of detail that enable their construction. The concepts, notions, and terminology introduced here

form an underlying basis for understanding the role and

Software design plays an important role in developing scope of software design.

software: it allows software engineers to produce various

models that form a kind of blueprint of the solution to be 1.1. General Design Concepts

implemented. We can analyze and evaluate these models to Software is not the only field where design is involved. In

determine whether or not they will allow us to fulfill the the general sense, we can view design as a form of problem-

various requirements. We can also examine and evaluate solving. [Bud03:c1] For example, the concept of a wicked

various alternative solutions and trade-offs. Finally, we can problem–a problem with no definitive solution–is interesting

use the resulting models to plan the subsequent develop- in terms of understanding the limits of design. [Bud04:c1] A

ment activities, in addition to using them as input and the number of other notions and concepts are also of interest in

starting point of construction and testing. understanding design in its general sense: goals, constraints,

In a standard listing of software life cycle processes such as alternatives, representations, and solutions. [Smi93]

IEEE/EIA 12207 Software Life Cycle Processes 1.2. Context of Software Design

[IEEE12207.0-96], software design consists of two activi-

To understand the role of software design, it is important to

ties that fit between software requirements analysis and

understand the context in which it fits, the software engi-

software construction:

neering life cycle. Thus, it is important to understand the

Software architectural design (sometimes called top- major characteristics of software requirements analysis vs.

level design): describing software’s top-level structure software design vs. software construction vs. software

and organization and identifying the various compo- testing. [IEEE12207.0-96]; Lis01:c11; Mar02; Pfl01:c2;

nents Pre04:c2]

Software detailed design: describing each component

sufficiently to allow for its construction.

© IEEE – 2004 Version 3–1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-51-320.jpg)

![1.3. Software Design Process 1.4.2. Coupling and cohesion

Software design is generally considered a two-step process: Coupling is defined as the strength of the relation-

[Bas03; Dor02:v1c4s2; Fre83:I; IEEE12207.0-96]; ships between modules, whereas cohesion is defined

Lis01:c13; Mar02:D] by how the elements making up a module are re-

1.3.1. Architectural Design lated. [Bas98:c6; Jal97:c5; Pfl01:c5; Pre04:c9]

Architectural design describes how software is de- 1.4.3. Decomposition and modularization

composed and organized into components (the soft- Decomposing and modularizing large software into a

ware architecture) [IEEEP1471-00] number of smaller independent ones, usually with

1.3.2. Detailed Design the goal of placing different functionalities or re-

sponsibilities in different components. [Bas98:c6;

Detailed design describes the specific behavior of

Bus96:c6; Jal97 :c5; Pfl01:c5; Pre04:c9]

these components.

1.4.4. Encapsulation/information hiding

The output of this process is a set of models and artifacts

Encapsulation/information hiding means grouping

that record the major decisions that have been taken.

and packaging the elements and internal details of an

[Bud04:c2; IEE1016-98; Lis01:c13; Pre04:c9

abstraction and making those details inaccessible.

1.4. Enabling Techniques [Bas98:c6; Bus96:c6; Jal97:c5; Pfl01:c5; Pre04:c9]

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a principle is 1.4.5. Separation of interface and implementation

“a basic truth or a general law … that is used as a basis of Separating interface and implementation involves

reasoning or a guide to action.” Software design principles, defining a component by specifying a public inter-

also called enabling techniques [Bus96], are key notions face, known to the clients, separate from the details

considered fundamental to many different software design of how the component is realized. [Bas98:c6;

approaches and concepts. The enabling techniques are the Bos00:c10; Lis01:c1,c9]

following: [Bas98:c6; Bus96:c6; IEEE1016-98; Jal97:c5,c6; 1.4.6. Sufficiency, completeness and primitiveness

Lis01:c1,c3; Pfl01:c5; Pre04:c9]

Achieving sufficiency, completeness, and primitive-

1.4.1. Abstraction ness means ensuring that a software component cap-

Abstraction is “the process of forgetting information tures all the important characteristics of an abstrac-

so that things that are different can be treated as if tion, and nothing more. [Bus96:c6; Lis01:c5]

they were the same”. [Lis01] In the context of soft-

ware design, two key abstraction mechanisms are

parameterization and specification. Abstraction by

specification leads to three major kinds of abstrac-

tion: procedural abstraction, data abstraction and

control (iteration) abstraction. [Bas98:c6;

Jal97:c5,c6; Lis01:c1,c2,c5,c6; Pre04:c1]

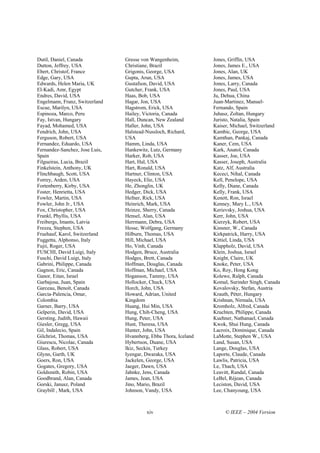

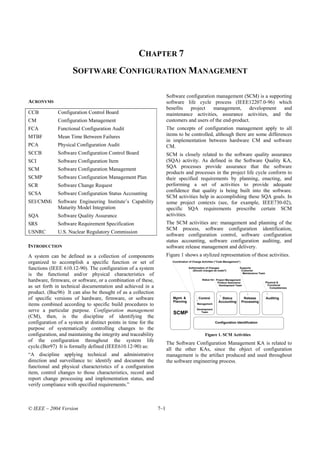

Software Design

Software Design Software Design

Software Design Key Issues in Software Structure Software

Quality Analysis Strategies and

Fundamentals Software Design and Architecture Design Notations

and Evaluation Methods

General design Quality attributes Structural General Strategies

Concurrency Architectural

concepts descriptions

structures and

(static view)

The context of Control and handling viewpoints

Quality analysis and Function-oriented

software design of events evaluation techniques Behavior descriptions (structured) design

Architectural styles

(dynamic view)

The software Distribution of (macroarchitectural Object-oriented

design process components patterns) Measures design

Error and exception Design patterns

handline and fault Data-structrure

(microarchitectural centered design

Enabling techniques tolerance patterns)

Interaction and Component-based

presentation Families of programs design

and frameworks

Data persistence

Other methods

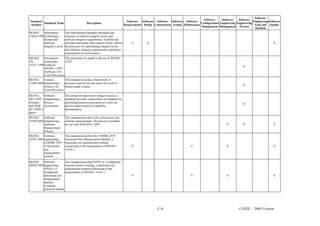

Figure 1 Breakdown of topics for the Software Design KA

3–2 © IEEE – 2004 Version](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-52-320.jpg)

![2. Key Issues in Software Design 3. Software Structure and Architecture

A number of key issues must be dealt with when designing In its strict sense, a software architecture is “a description

software. Some are quality concerns that all software must of the subsystems and components of a software system

address—for example, performance. Another important and the relationships between them”. (Bus96:c6) Architec-

issue is how to decompose, organize, and package software ture thus attempts to define the internal structure—

components. This is so fundamental that all design approa- according to the Oxford English Dictionary, “the way in

ches must address it in one way or another (see topic 1.4 which something is constructed or organized”—of the

Enabling Techniques and sub-area 6 Software Design resulting software. During the mid-1990s, however, soft-

Strategies and Mehtods). In contrast, other issues “deal with ware architecture started to emerge as a broader discipline

some aspect of software’s behavior that is not in the applica- involving the study of software structures and architectures

tion domain, but which addresses some of the supporting in a more generic way [Sha96]. This gave rise to a number

domains”. [Bos00] Such issues, which often cross-cut the of interesting ideas about software design at different levels

system’s functionality, have been referred to as aspects: of abstraction. Some of these concepts can be useful during

“[aspects] tend not to be units of software’s functional de- the architectural design (for example, architectural style) of

composition, but rather to be properties that affect the per- specific software, as well as during its detailed design (for

formance or semantics of the components in systemic example, lower-level design patterns). But they can also be

ways” (Kic97). A number of these key, cross-cutting issues useful for designing generic systems, leading to the design

are the following (presented in alphabetical order): of families of programs (also known as product lines).

2.1. Concurrency Interestingly, most of these concepts can be seen as at-

tempts to describe, and thus reuse, generic design knowl-

How to decompose the software into processes, tasks and edge.

threads and deal with related efficiency, atomicity, synchro-

nization, and scheduling issues. [Bos00:c5; Mar02:CSD; 3.1. Architectural Structures and Viewpoints

Mey97:c30; Pre04:c9] Different high-level facets of a software design can and

2.2. Control and Handling of Events should be described and documented. These facets are often

called views: “A view represents a partial aspect of a soft-

How to organize data and control flow, how to handle reac- ware architecture that shows specific properties of a soft-

tive and temporal events through various mechanisms such ware system” [Bus96:c6]. These distinct views pertain to

as implicit invocation and call-backs. [Bas98:c5; distinct issues associated with software design—for exam-

Mey97:c32; Pfl01:c5] ple, the logical view (satisfying the functional require-

2.3. Distribution of Components ments) vs. the process view (concurrency issues) vs. the

How to distribute the software across the hardware, how physical view (distribution issues) vs. the development

the components communicate, how middleware can be view (how the design is broken down into implementation

used to deal with heterogeneous software. [Bas03:c16; units). Other authors use different terminologies, like be-

Bos00:c5; Bus96:c2 Mar94:DD; Mey97:c30; Pre04:c30] havioral vs. functional vs. structural vs. data modeling

views. In summary, a software design is a multi-faceted

2.4. Error and Exception Handling and Fault Tolerance artifact produced by the design process and generally com-

How to prevent and tolerate faults and deal with excep- posed of relatively independent and orthogonal views.

tional conditions. [Lis01:c4; Mey97:c12; Pfl01:c5] [Bas03:c2; Boo99:c31; Bud04:c5; Bus96:c6; IEEE1016-98;

IEEE1471-00]Architectural Styles (macroarchitectural pat-

2.5. Interaction and Presentation

terns)

How to structure and organize the interactions with users

An architectural style is “a set of constraints on an architec-

and the presentation of information (for example, separa-

tion of presentation and business logic using the Model- ture [that] defines a set or family of architectures that satis-

fies them” [Bas03:c2]. An architectural style can thus be

View-Controller approach). [Bas98:c6; Bos00:c5;

Bus96:c2; Lis01:c13; Mey97:c32] It is to be noted that this seen as a meta-model which can provide software’s high-

topic is not about specifying user interface details, which is level organization (its macroarchitecture). Various authors

the task of user interface design (a part of Software Ergo- have identified a number of major architectural styles.

nomics); see Related Disciplines of Software Engineering. [Bas03:c5; Boo99:c28; Bos00:c6; Bus96:c1,c6; Pfl01:c5]

General structure (for example, layers, pipes and fil-

2.6. Data Persistence

ters, blackboard)

How long-lived data are to be handled. [Bos00:c5;

Mey97:c31] Distributed systems (for example, client-server, three-

tiers, broker)

Interactive systems (for example, Model-View-

Controller, Presentation-Abstraction-Control)

© IEEE – 2004 Version 3–3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ieee-guide-to-the-software-engineering-body-of-knowlewdge-2004-version-swebok-2005-091124024426-phpapp02/85/Ieee-Guide-To-The-Software-Engineering-Body-Of-Knowlewdge-2004-Version-Swebok-2005-53-320.jpg)

![Adaptable systems (for example, micro-kernel, reflec- 4.2. Quality Analysis and Evaluation Techniques

tion) Various tools and techniques can help ensure a software

Others (for example, batch, interpreters, process con- design’s quality.

trol, rule-based). Software design reviews: informal or semiformal, often

3.2. Design Patterns (microarchitectural patterns) group-based, techniques to verify and ensure the qual-

Succinctly described, a pattern is “a common solution to a ity of design artifacts (for example, architecture re-

common problem in a given context”. (Jac99) While archi- views [Bas03:c11], design reviews and inspections

tectural styles can be viewed as patterns describing the [Bud04:c4; Fre83:VIII; IEEE1028-97; Jal97:c5,c7;

high-level organization of software (their macroarchitec- Lis01:c14; Pfl01:c5], scenario-based techniques

ture), other design patterns can be used to describe details [Bas98:c9; Bos00:c5], requirements tracing

at a lower, more local level (their microarchitecture). [Dor02:v1c4s2; Pfl01:c11])

[Bas98:c13; Boo99:c28; Bus96:c1; Mar02:DP] Static analysis: formal or semiformal static (non-

Creational patterns (for example, builder, factory, executable) analysis that can be used to evaluate a de-

prototype, and singleton) sign (for example, fault-tree analysis or automated

cross-checking) [Jal97:c5; Pfl01:c5]