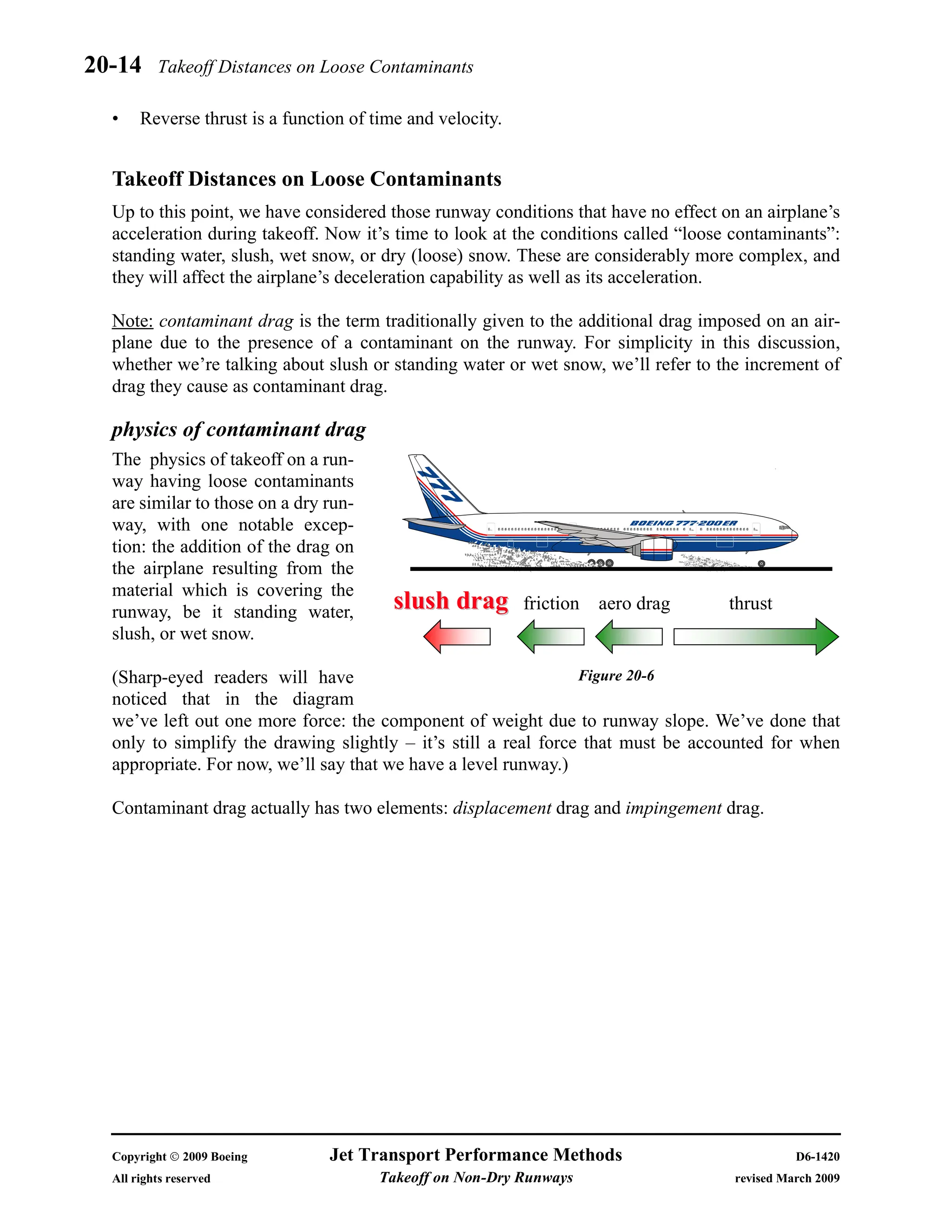

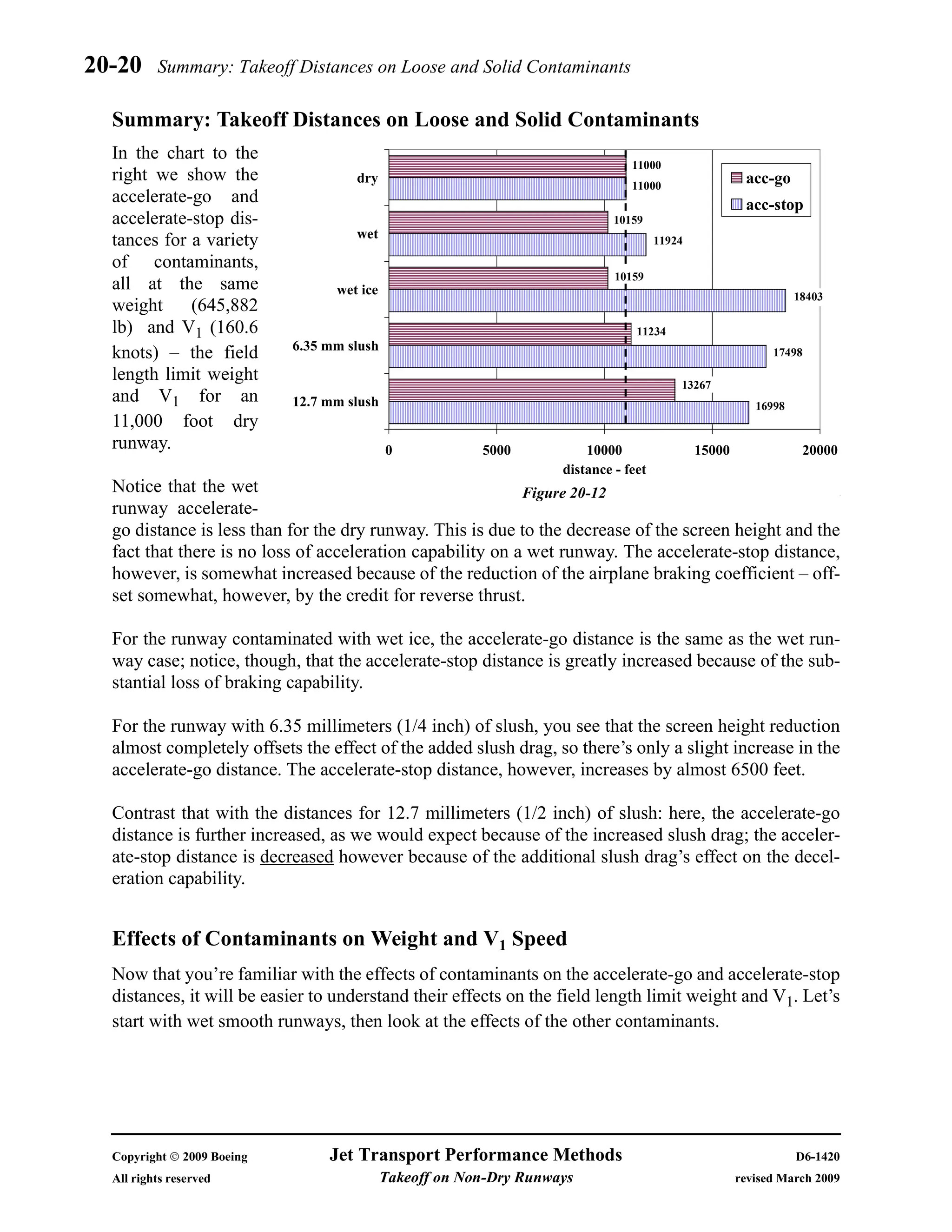

The document discusses the impact of loose contaminants like water, slush, and snow on aircraft takeoff performance. It explains how these conditions create additional drag and affect aircraft acceleration and deceleration, including the concepts of contaminant drag and hydroplaning. Regulatory limits on maximum allowable contaminant depths for safe takeoff are also noted, highlighting the necessity of careful calculation of takeoff distances under these conditions.