The document provides recommendations and guidelines for diagnosing and managing heart failure during pregnancy. Key points include:

- Heart failure in pregnancy can occur due to various cardiac causes and conditions and may develop at any point during pregnancy.

- A multistep evaluation including history, exam, ECG, echocardiogram and labs should be performed if heart failure is suspected.

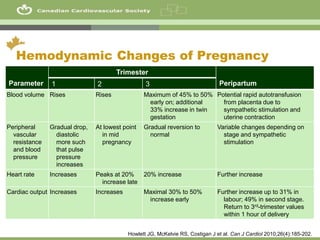

- Healthcare providers should be aware of the significant hemodynamic changes that normally occur during pregnancy, as these can uncover or exacerbate pre-existing heart conditions. Symptoms like dyspnea and edema are common in late pregnancy but progressive or severe symptoms suggest heart failure.