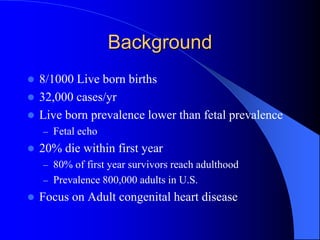

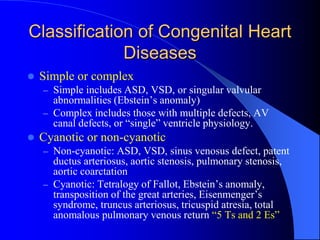

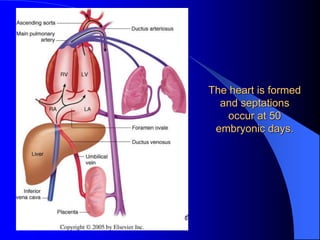

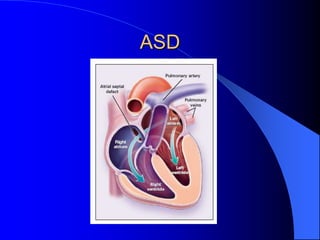

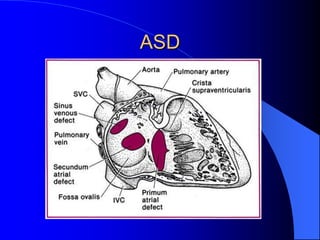

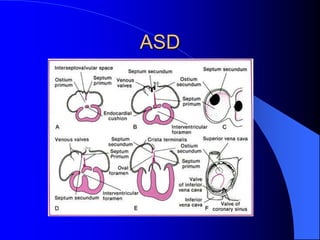

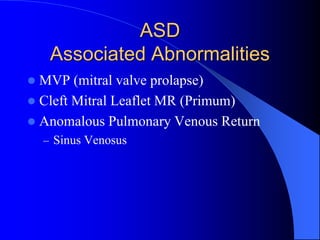

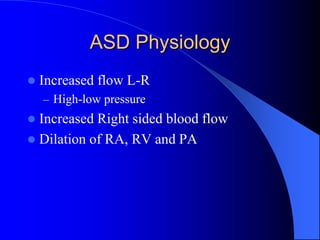

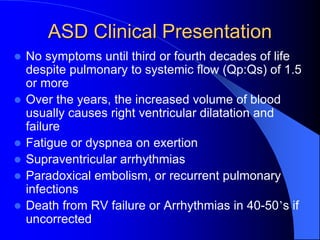

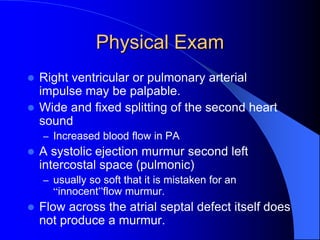

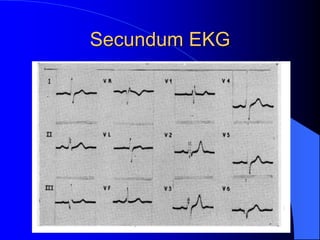

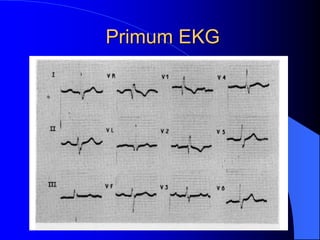

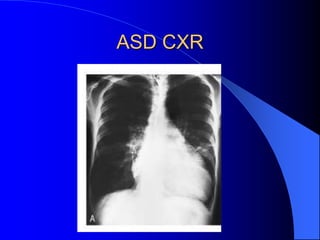

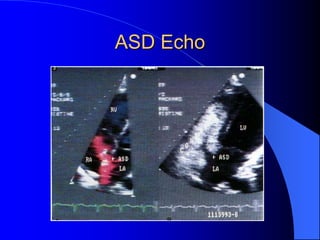

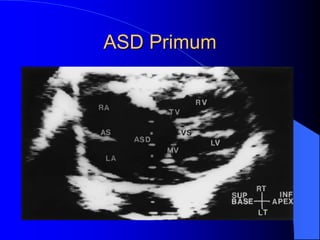

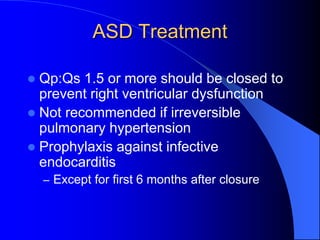

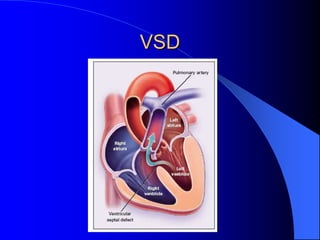

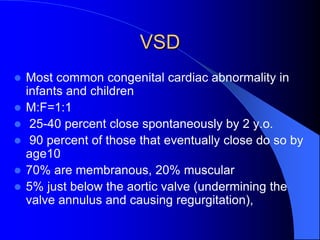

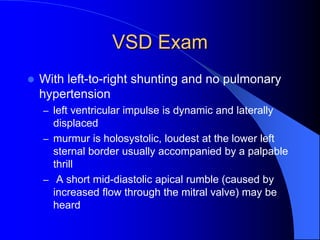

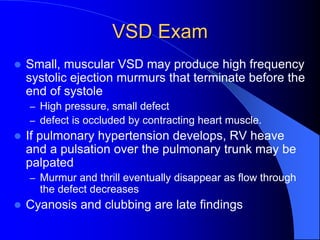

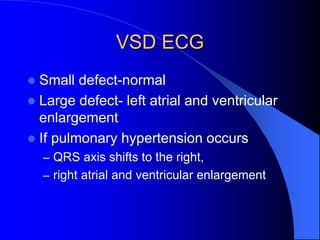

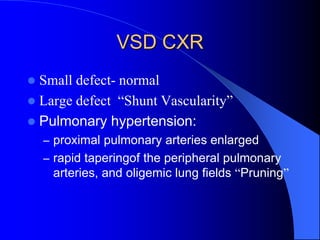

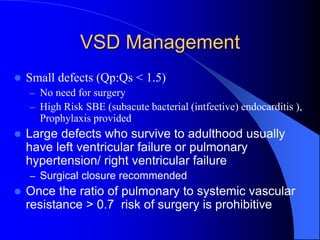

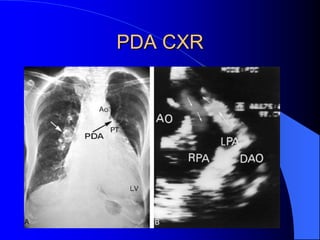

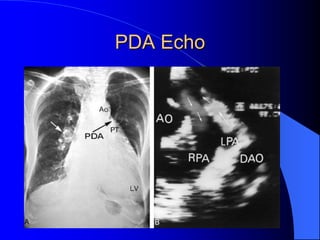

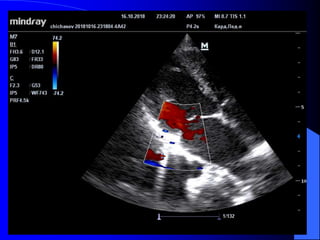

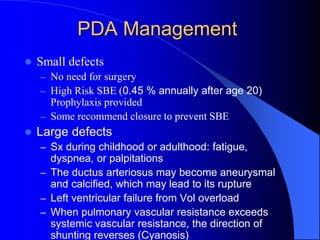

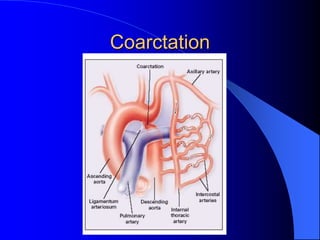

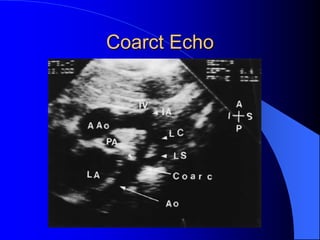

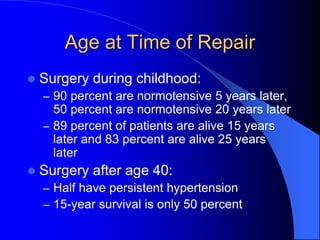

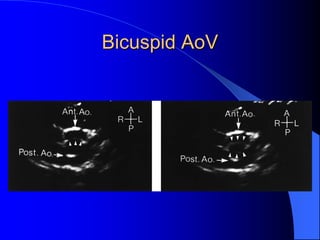

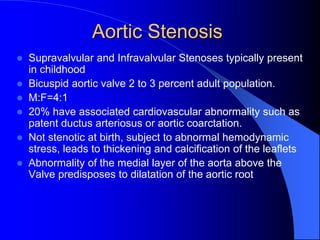

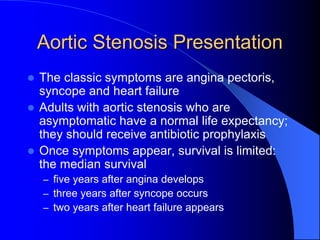

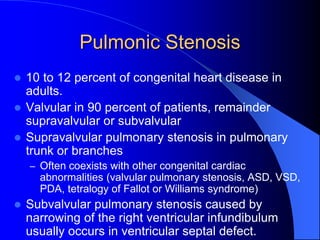

The document discusses several types of congenital heart disease that can present in adults, including atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, coarctation of the aorta, and bicuspid aortic valve. It provides details on the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic workup, and treatment options for each condition. The focus is on how these congenital heart defects are managed when patients reach adulthood rather than during childhood.