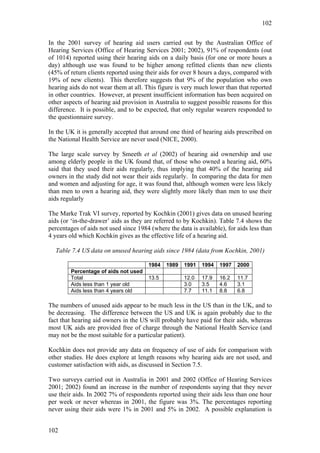

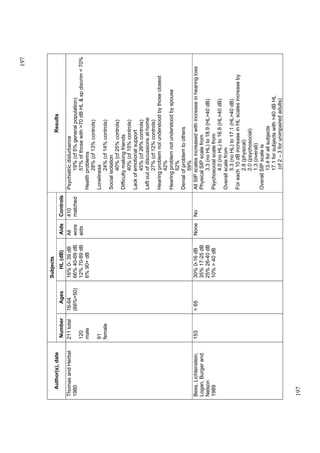

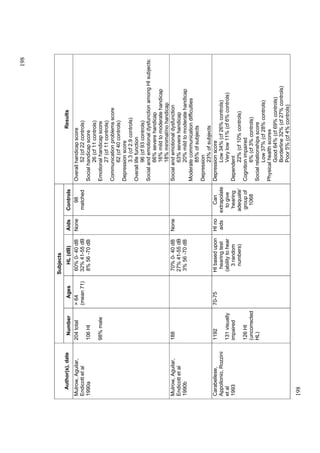

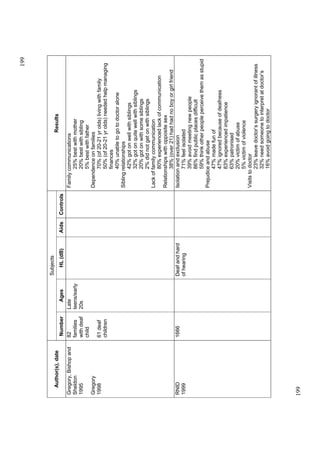

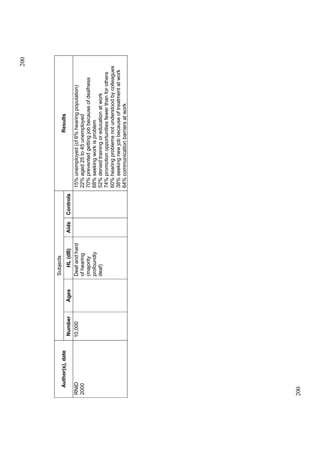

The report evaluates the social and economic impacts of hearing impairment in Europe, focusing on definitions, prevalence, psychosocial effects, ownership and use of hearing aids, and the associated costs. It identifies significant gaps in research, particularly regarding the effects of hearing loss on young adults and the economic burden of untreated hearing impairment. The findings underscore the necessity for further studies and highlight potential improvements in quality of life through effective hearing aid interventions.