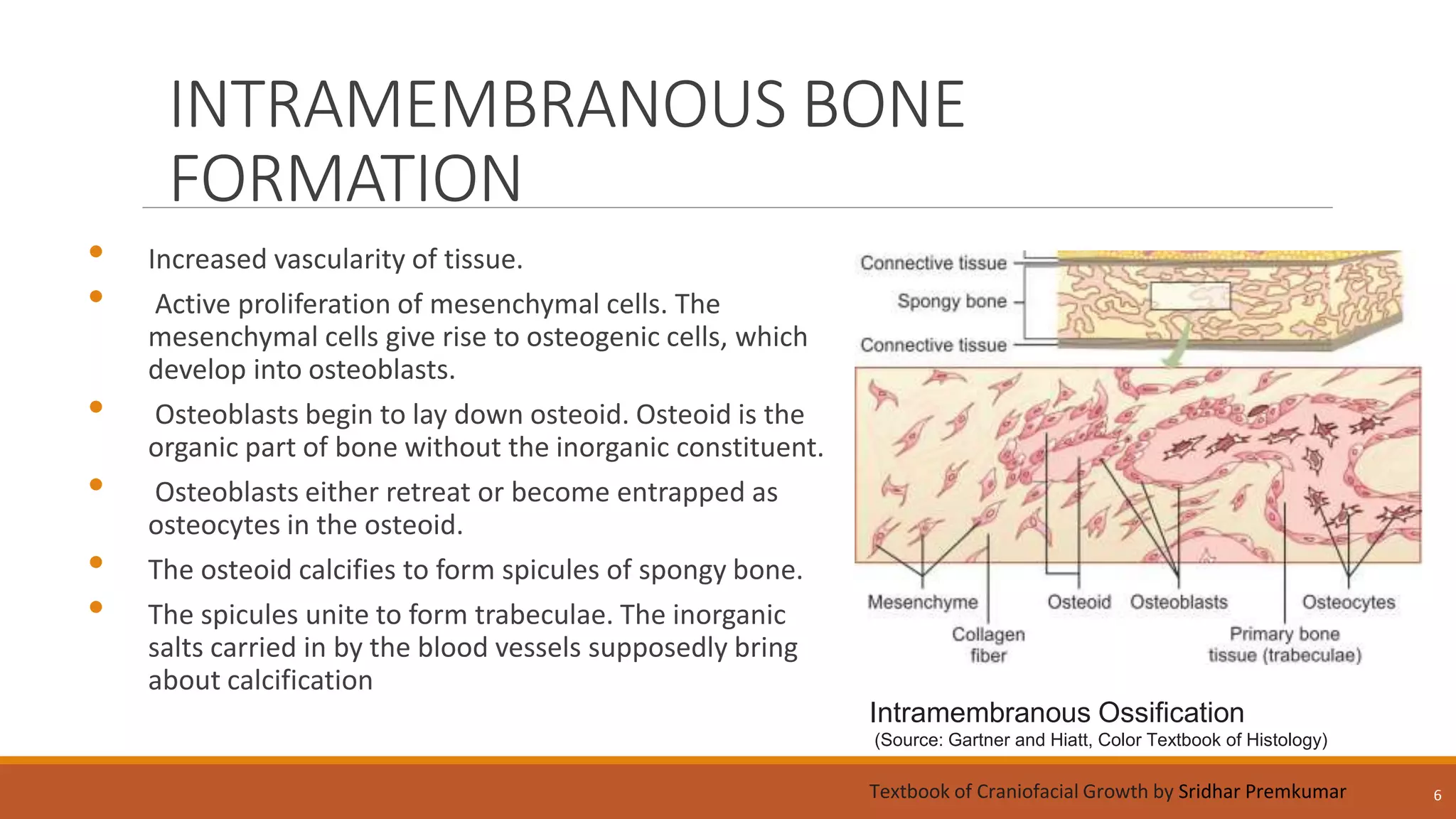

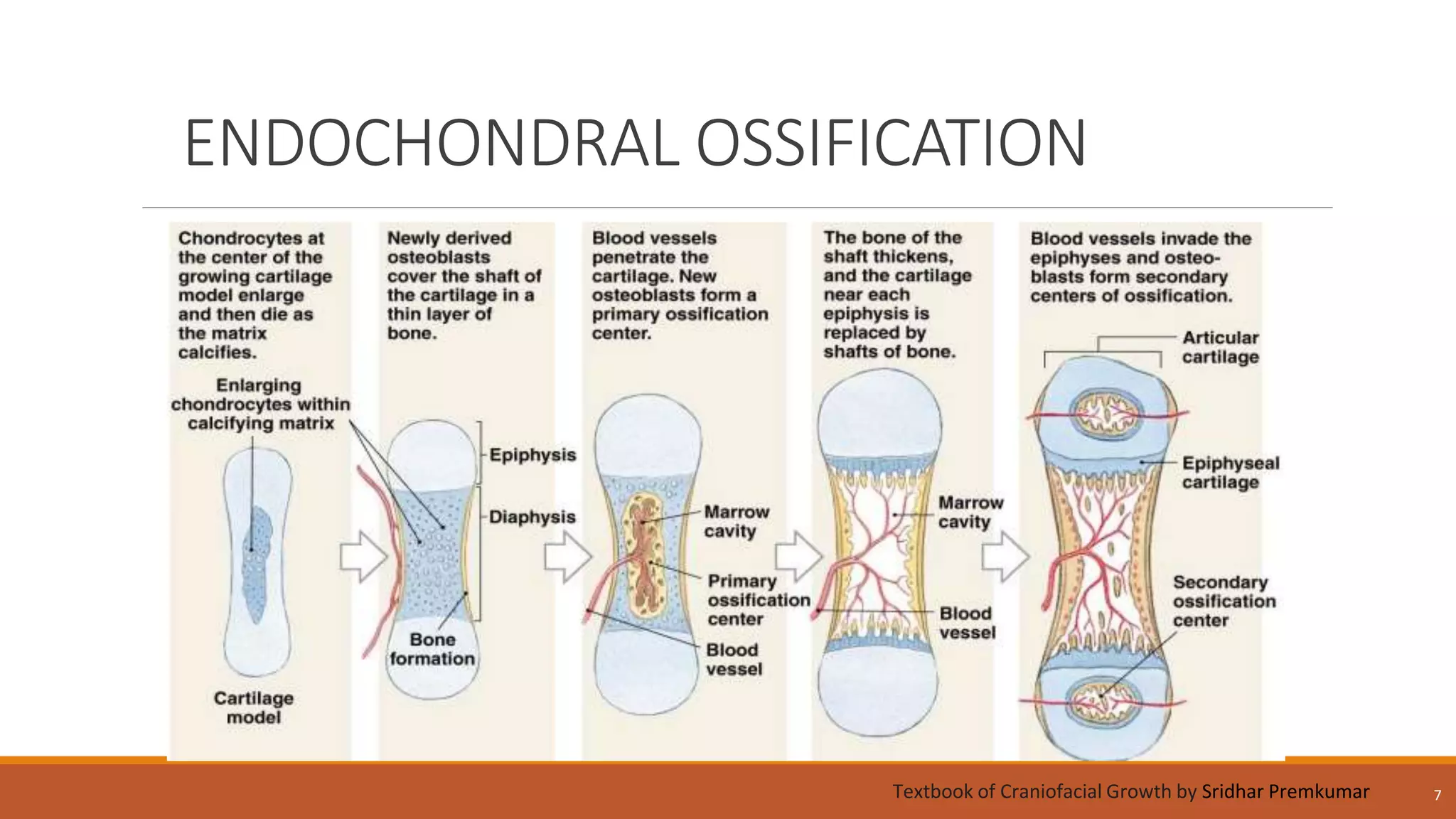

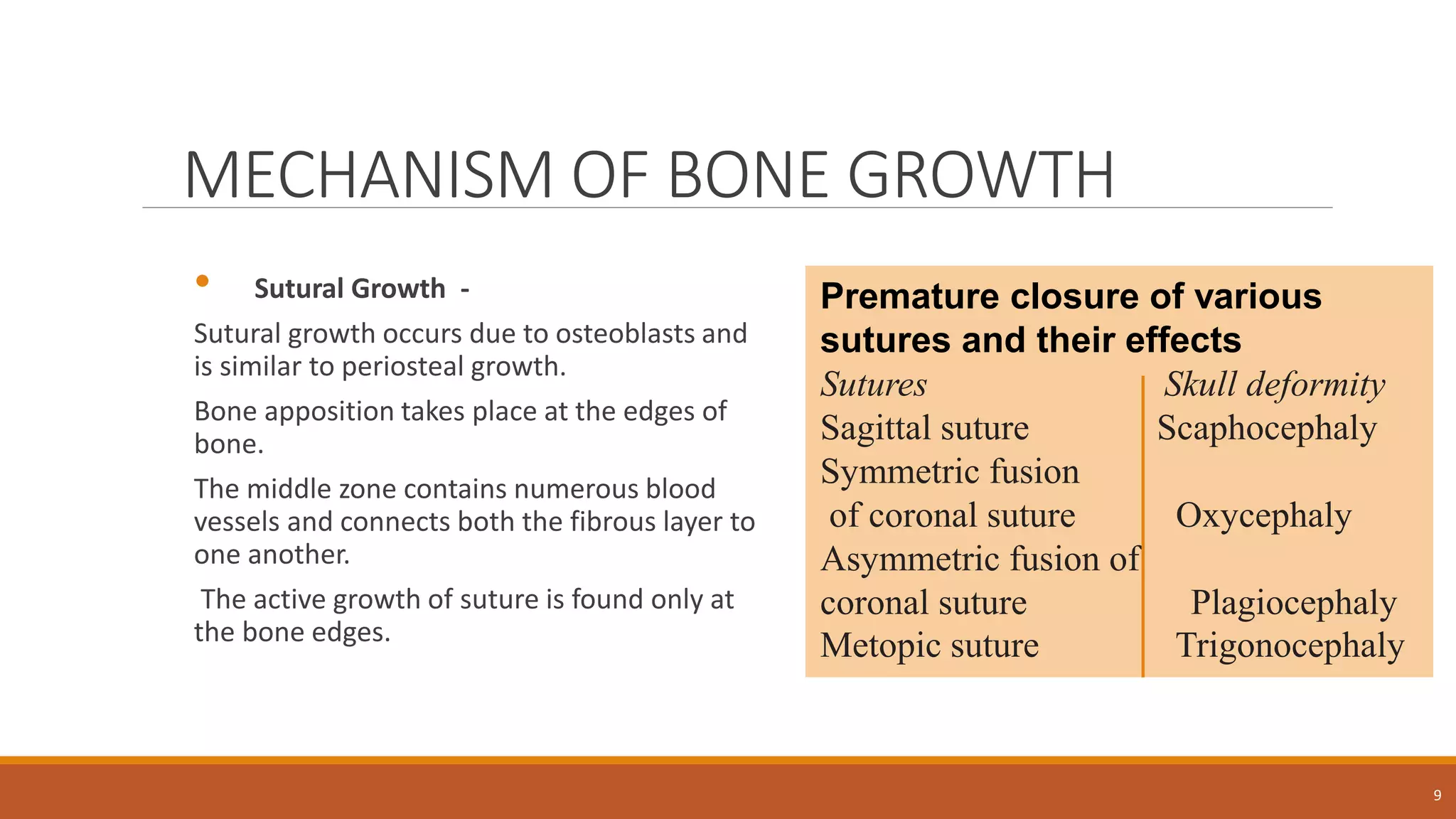

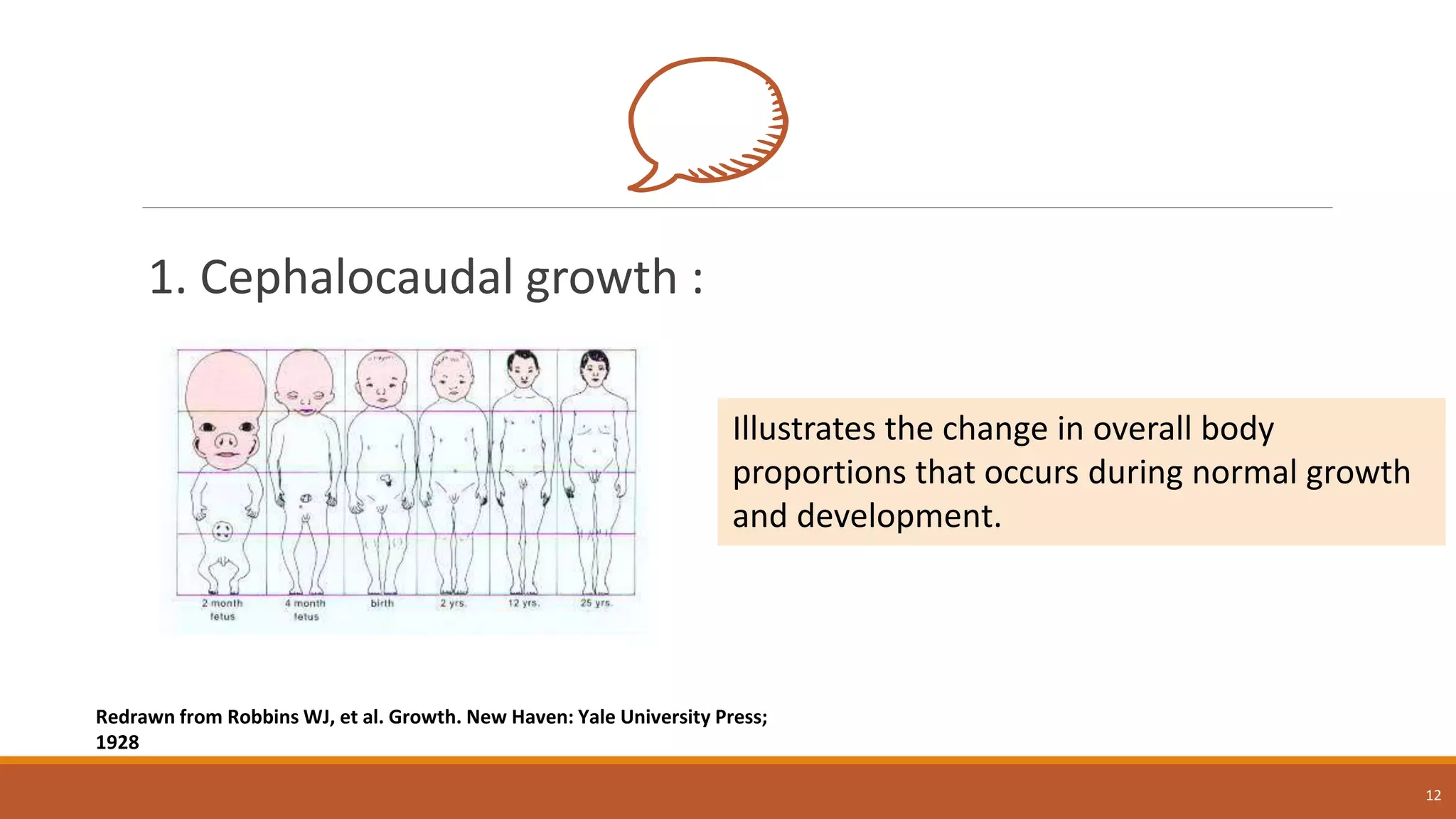

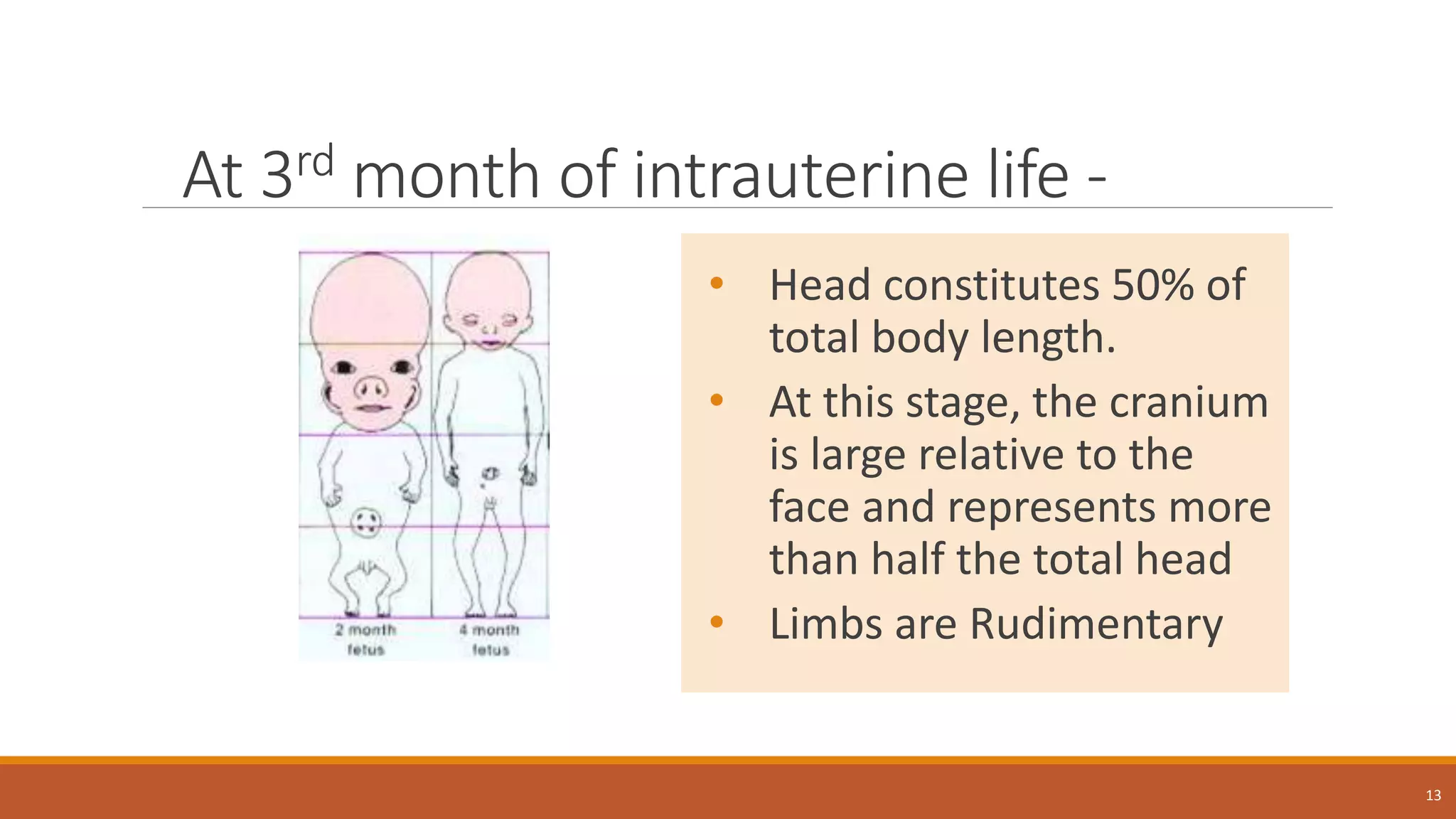

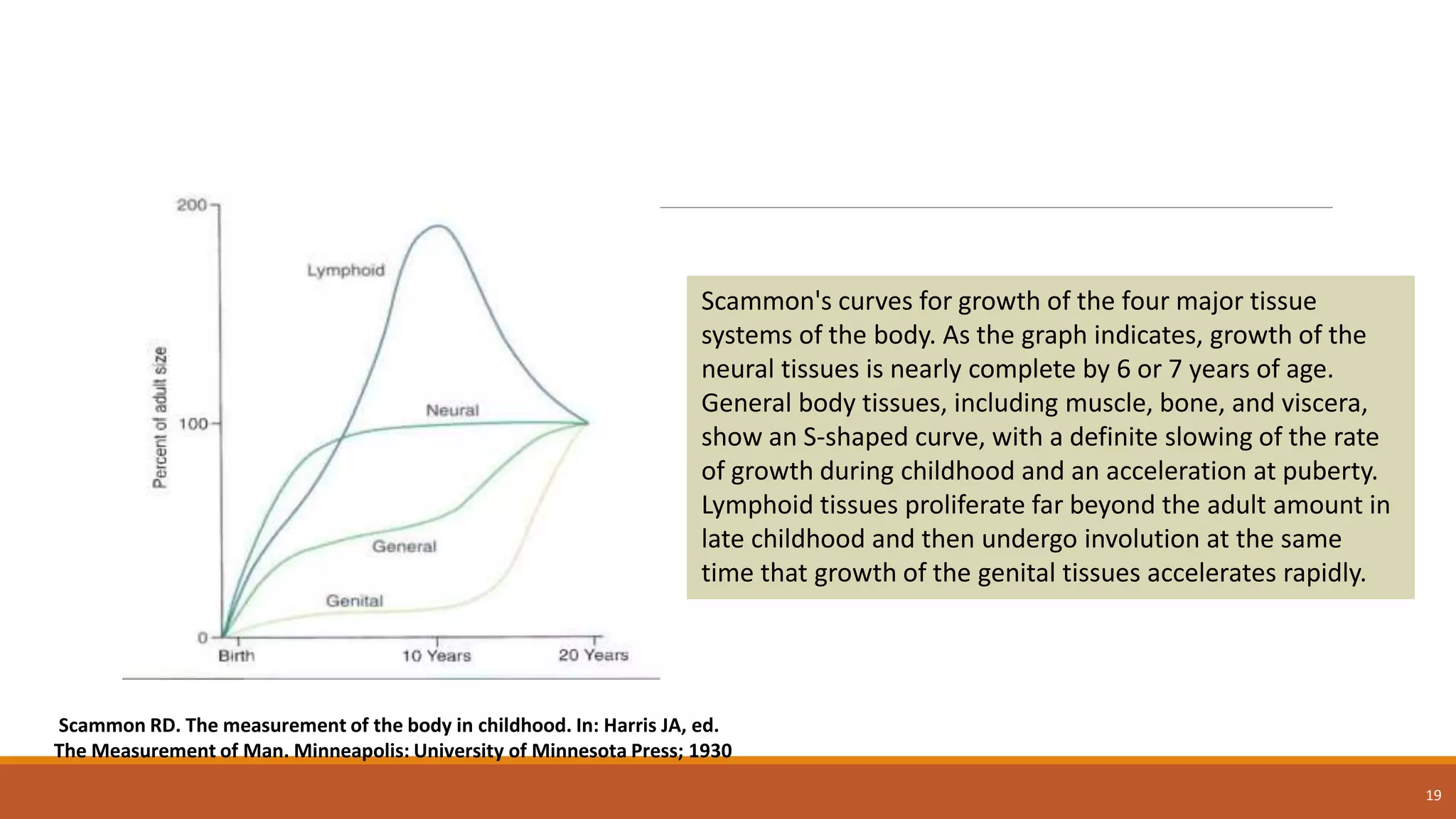

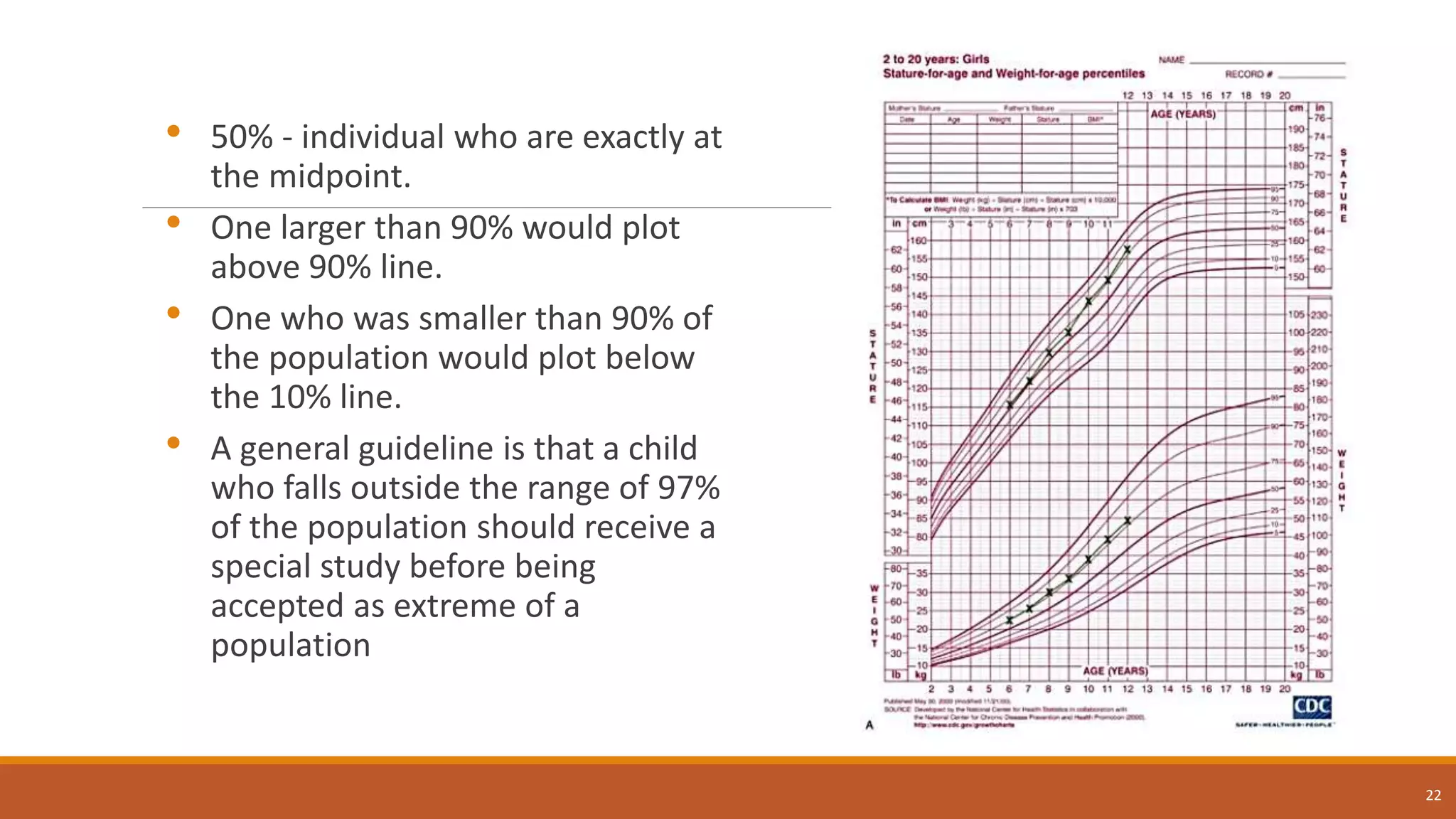

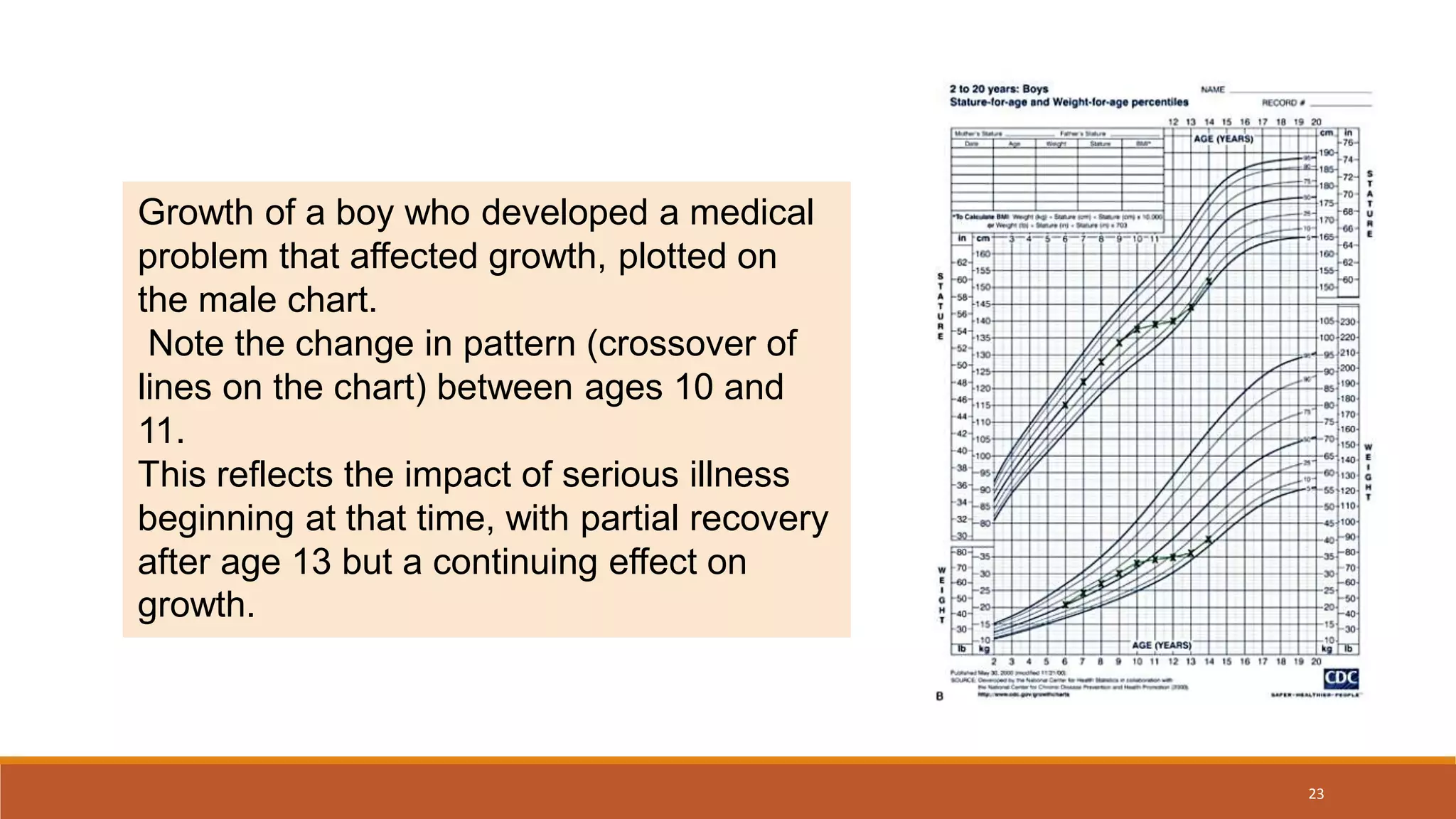

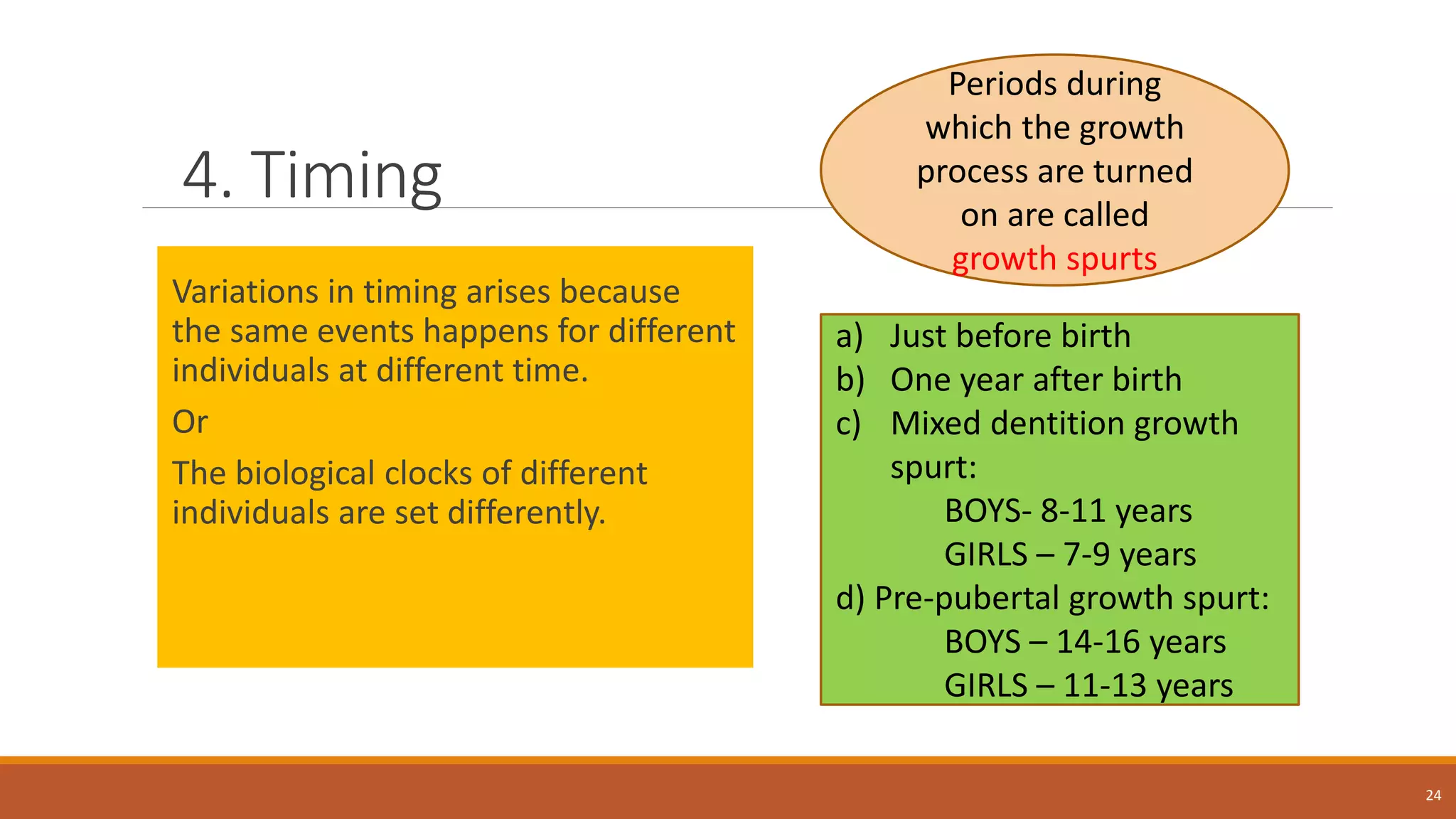

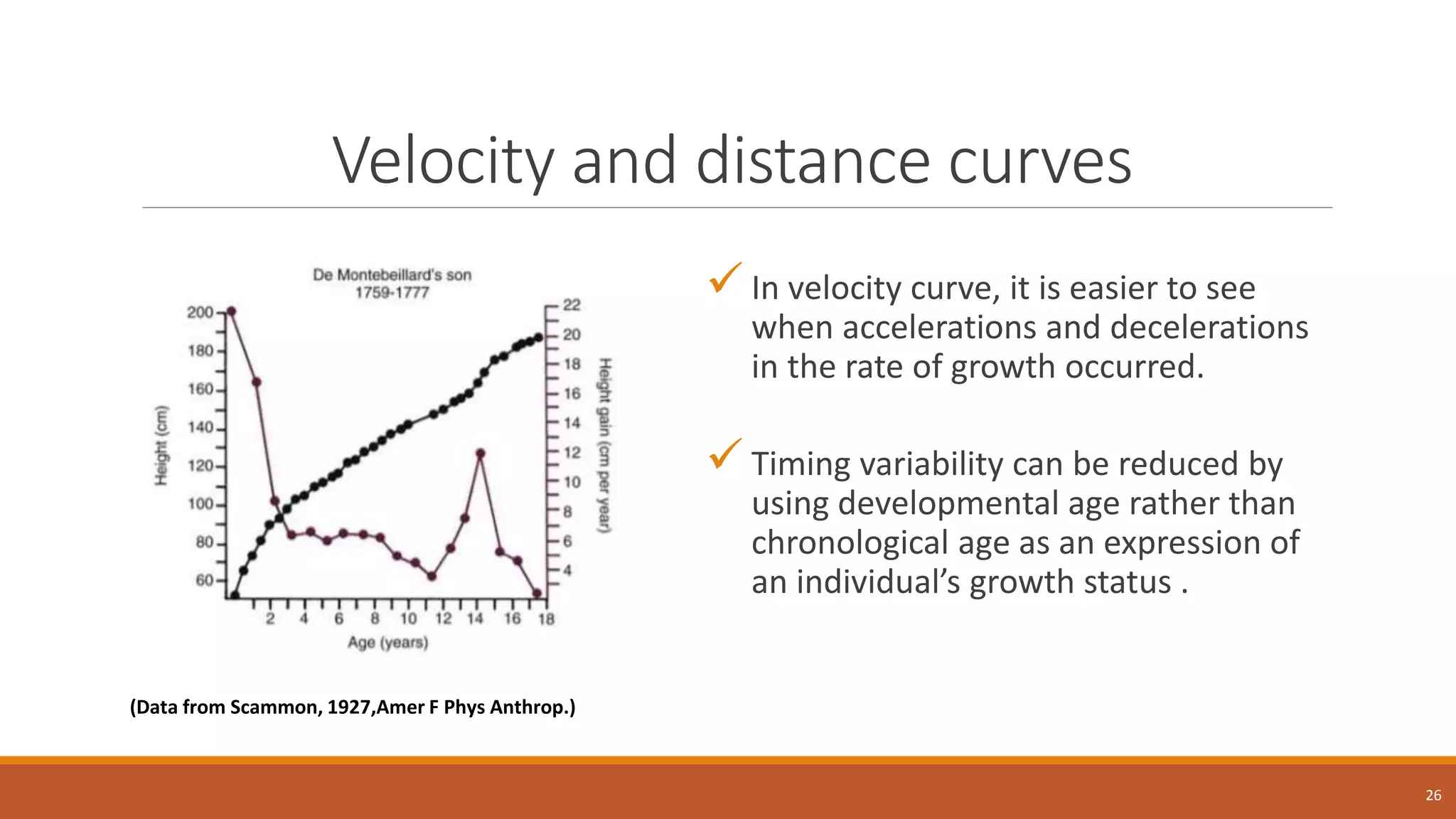

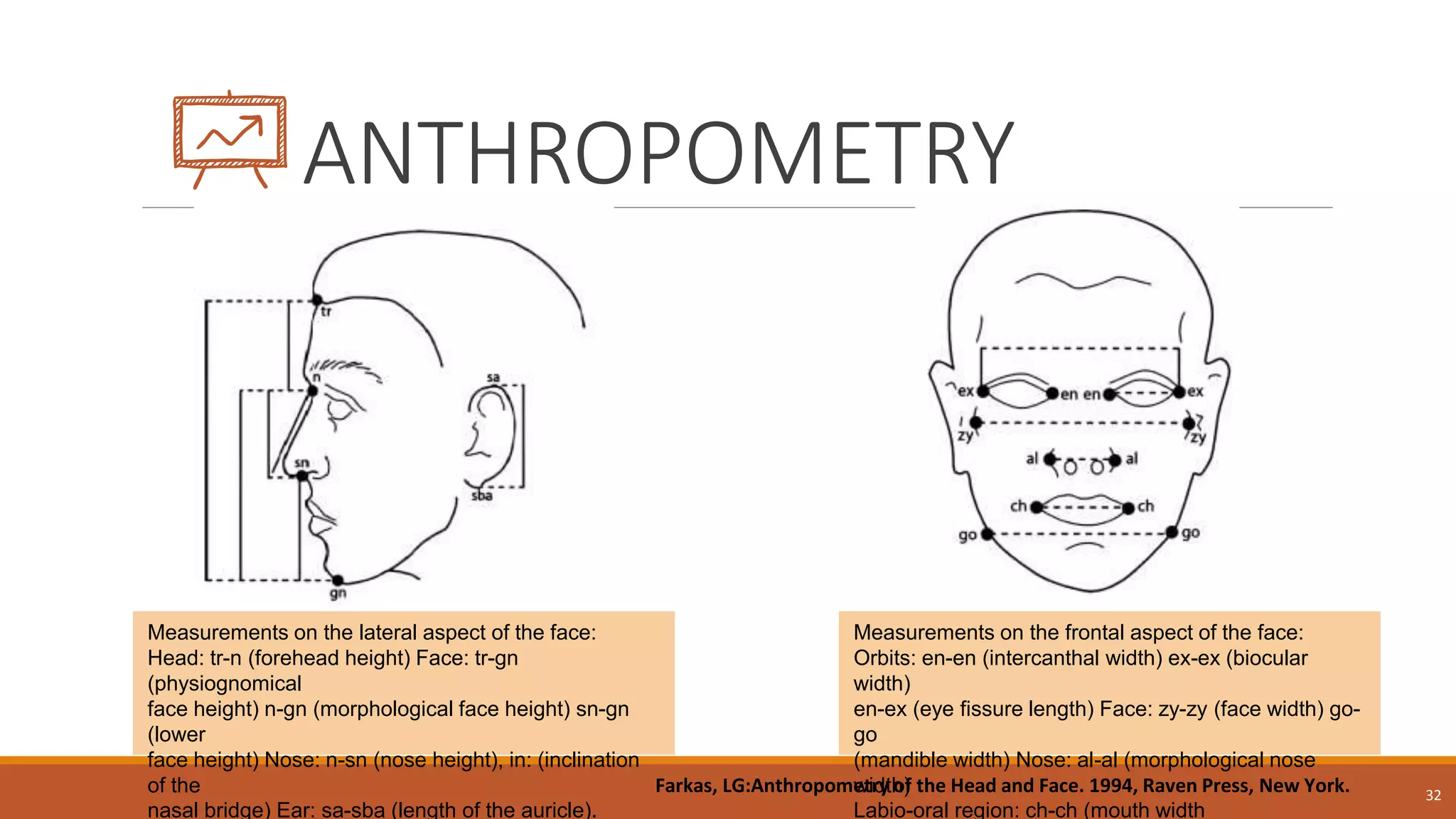

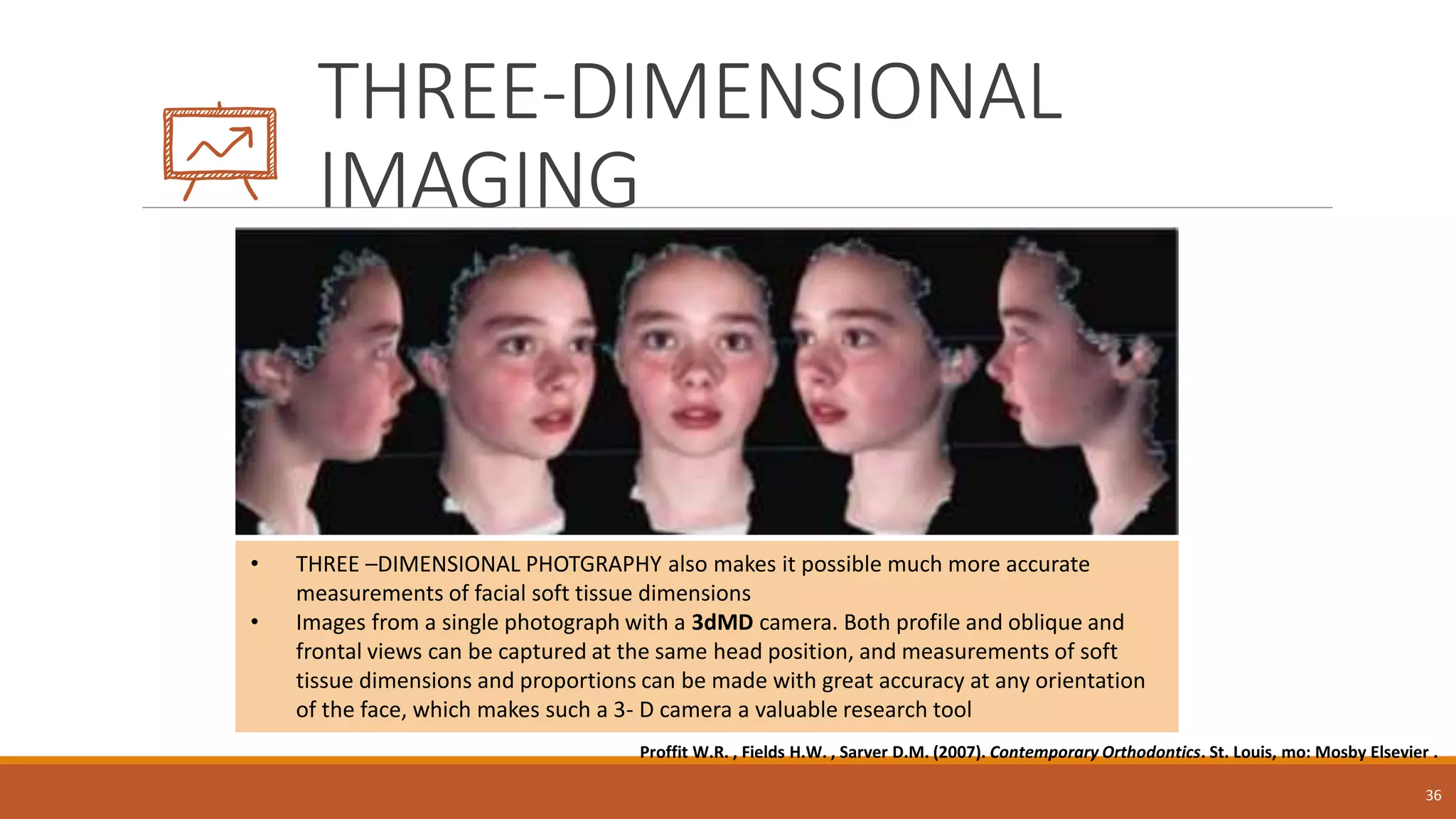

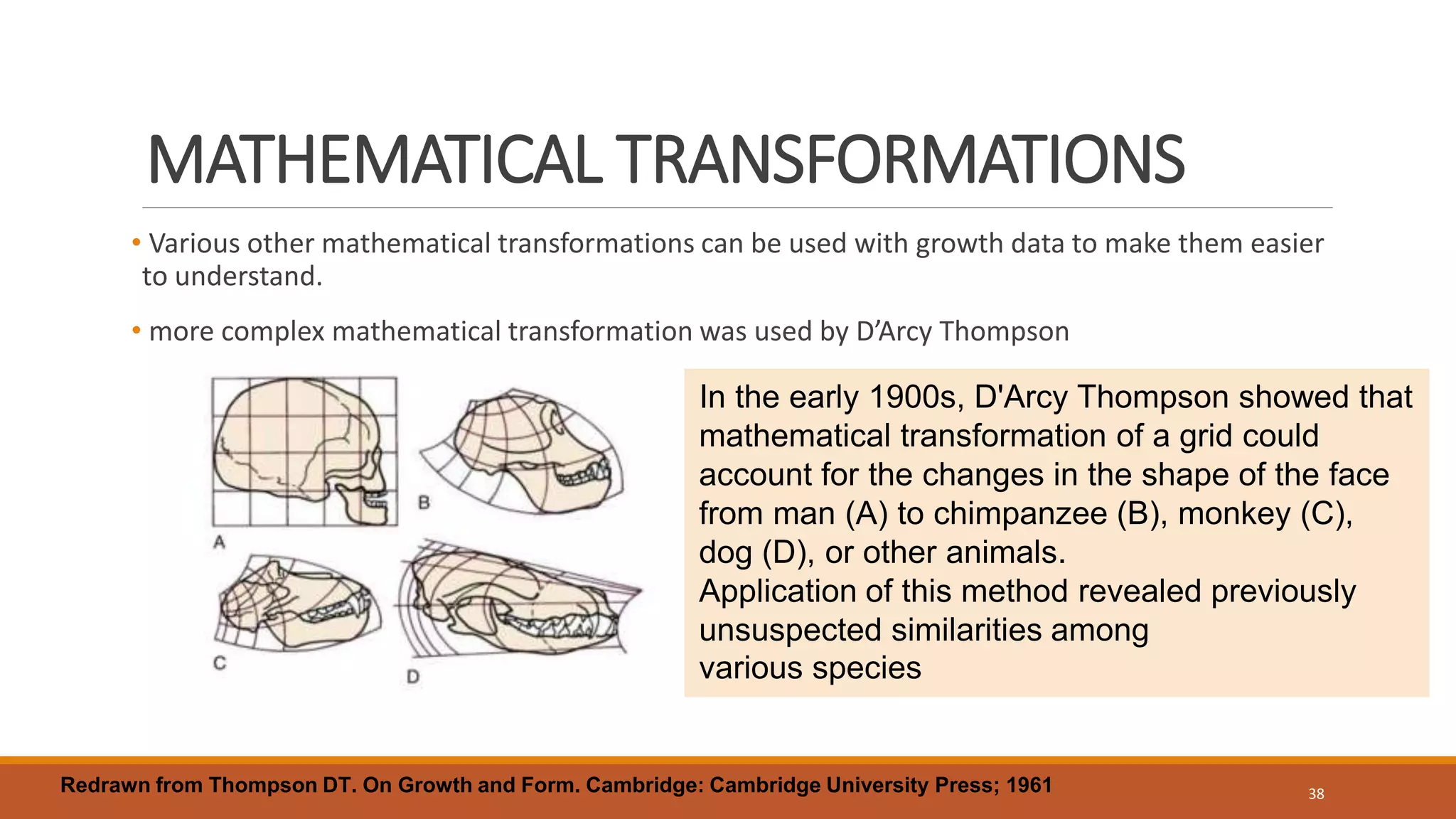

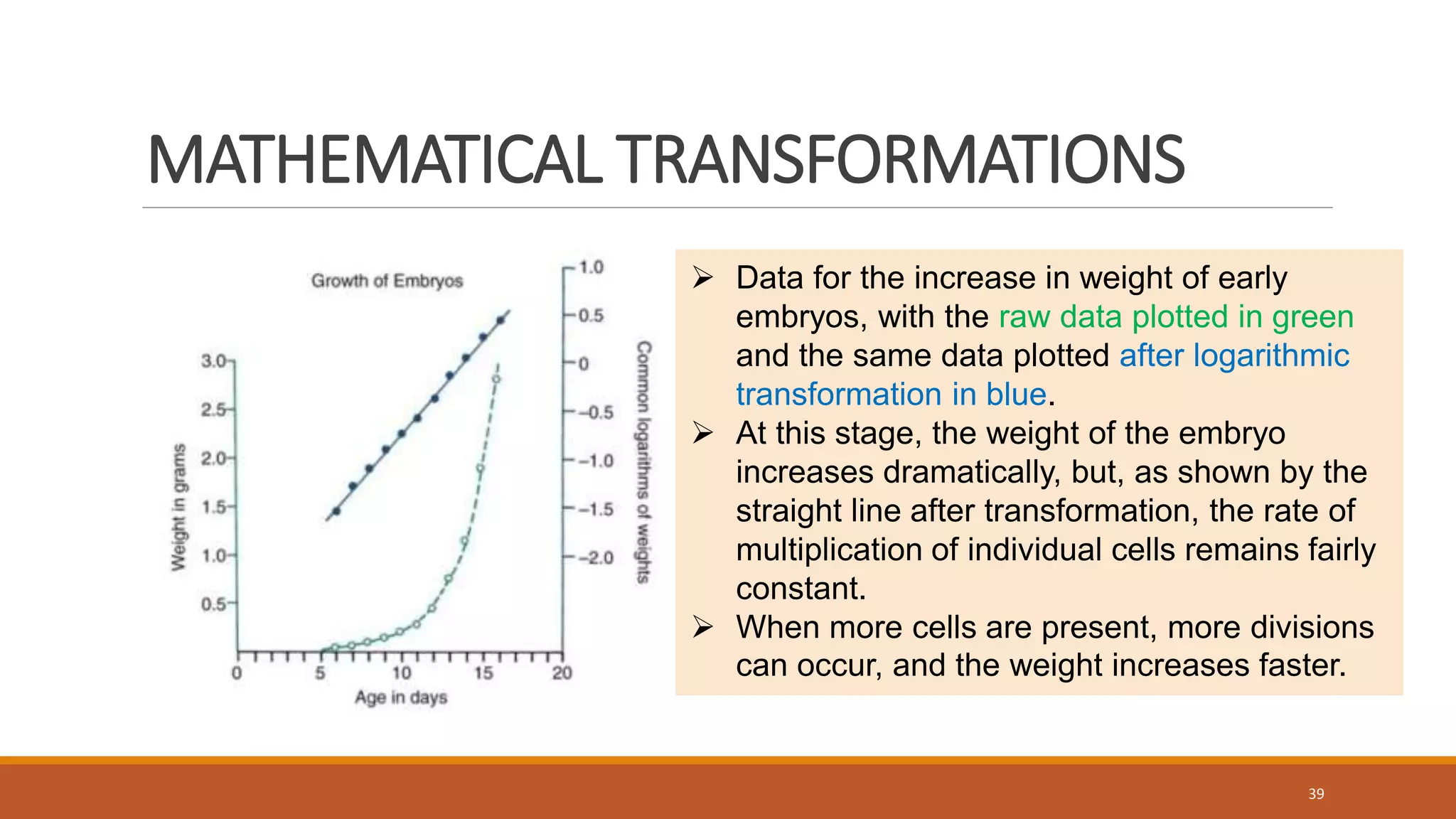

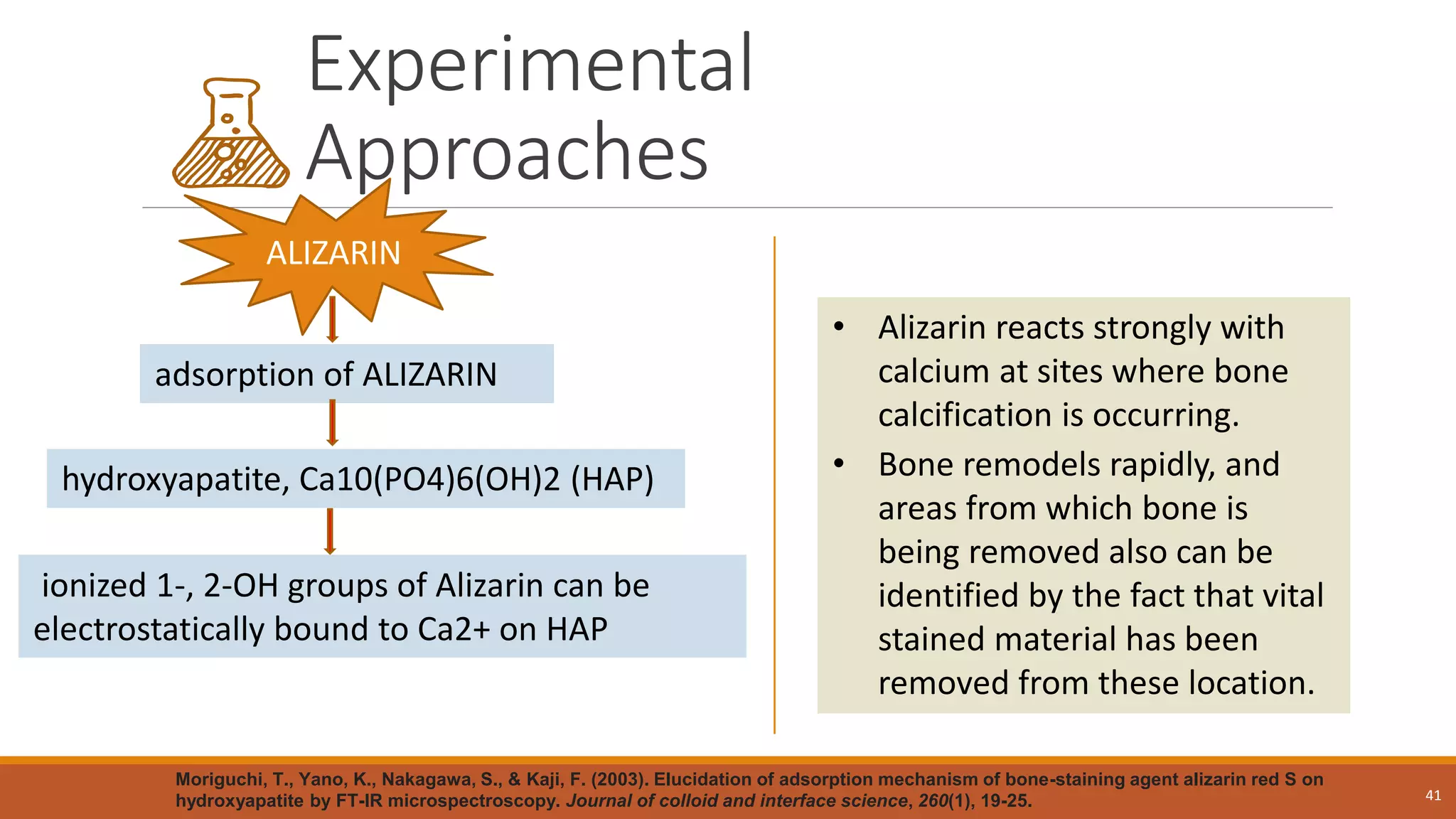

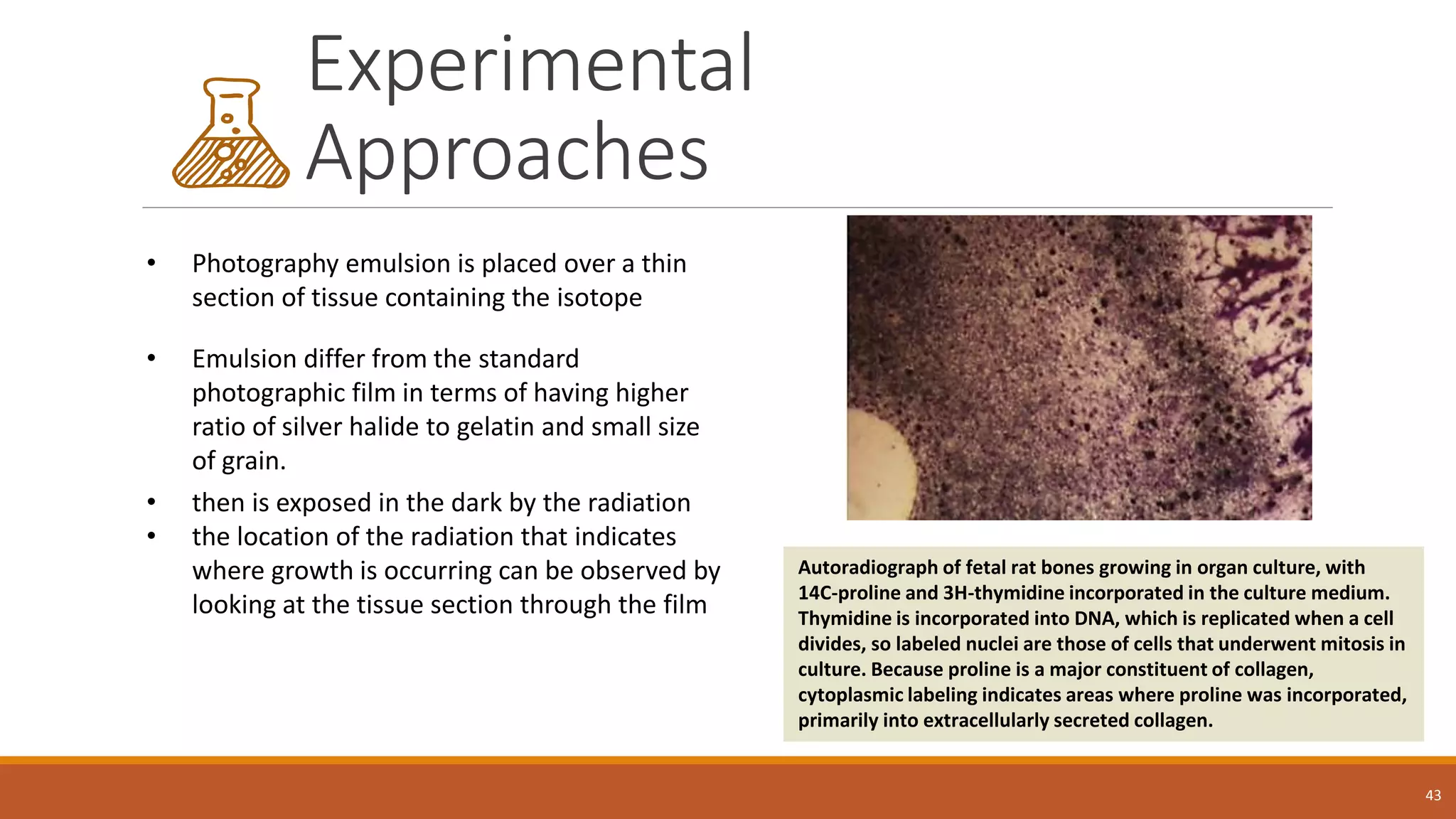

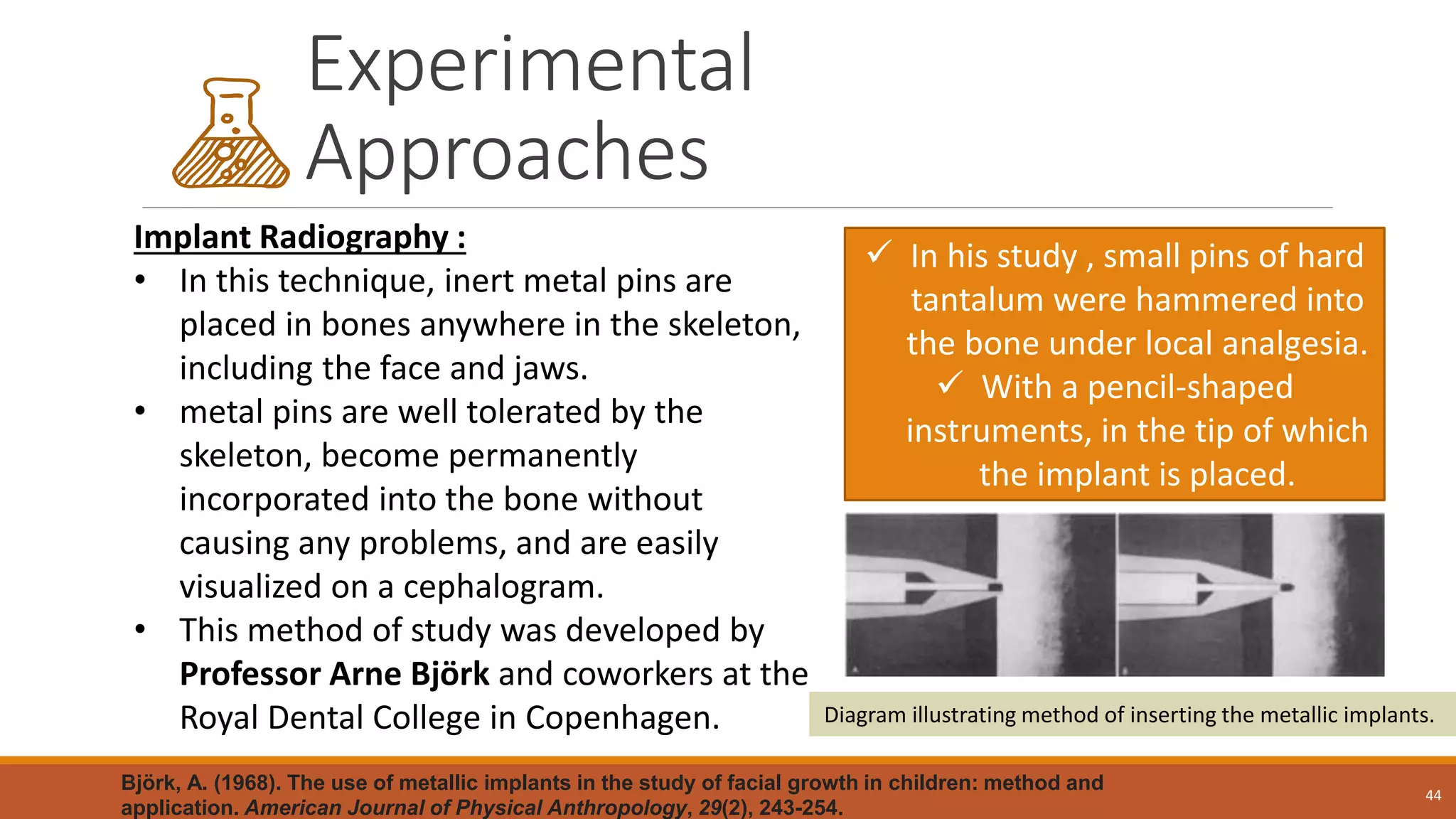

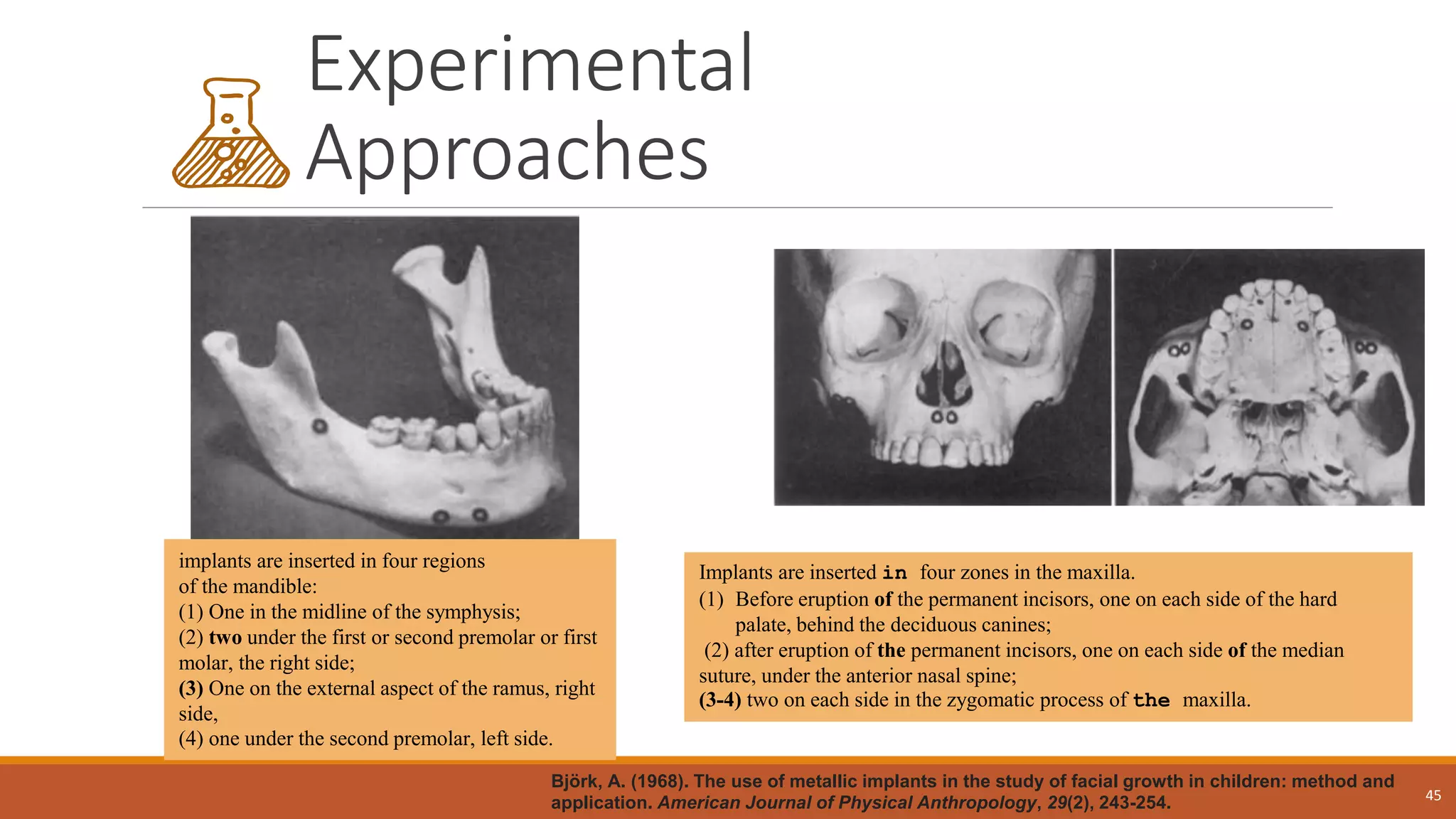

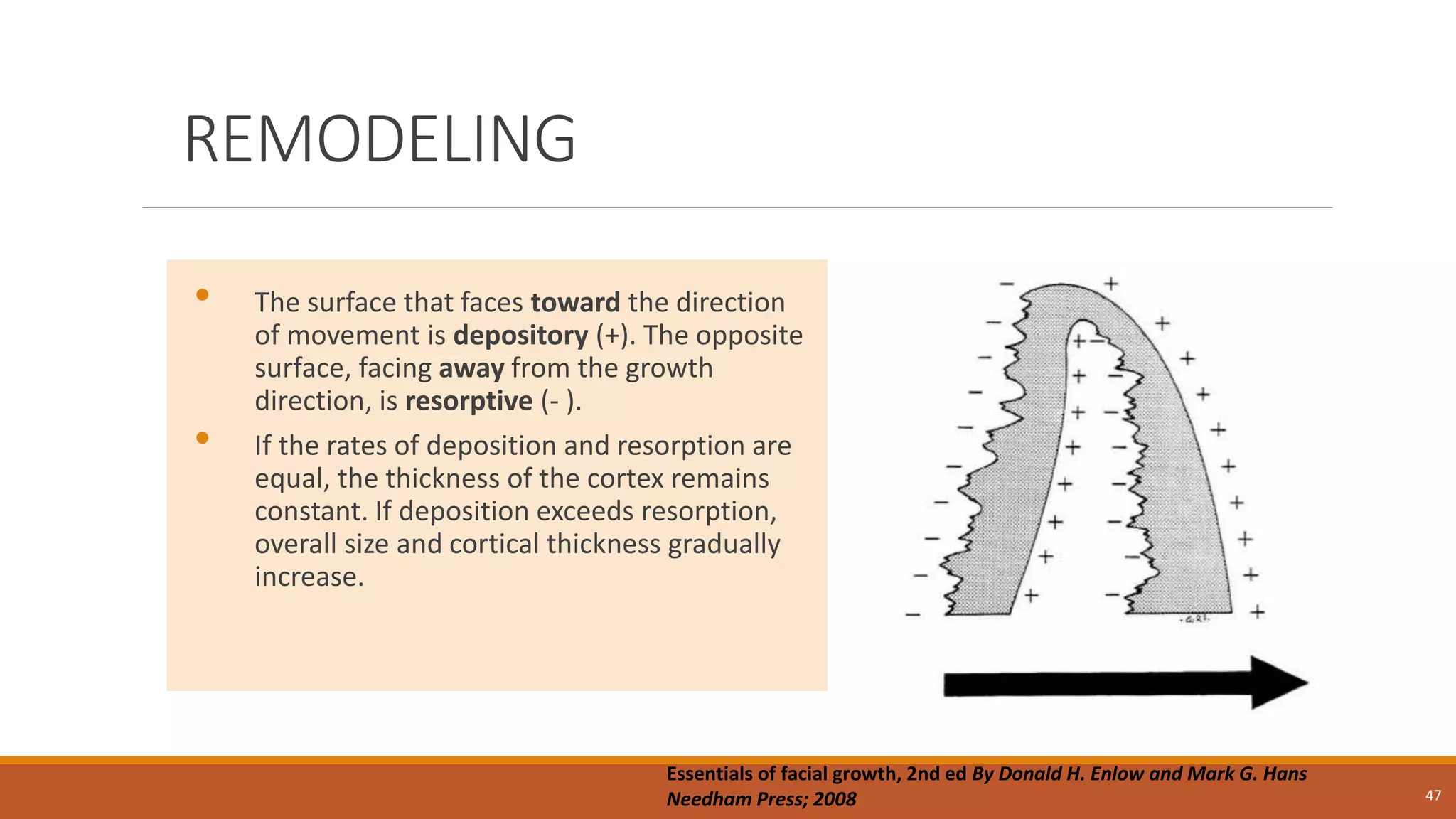

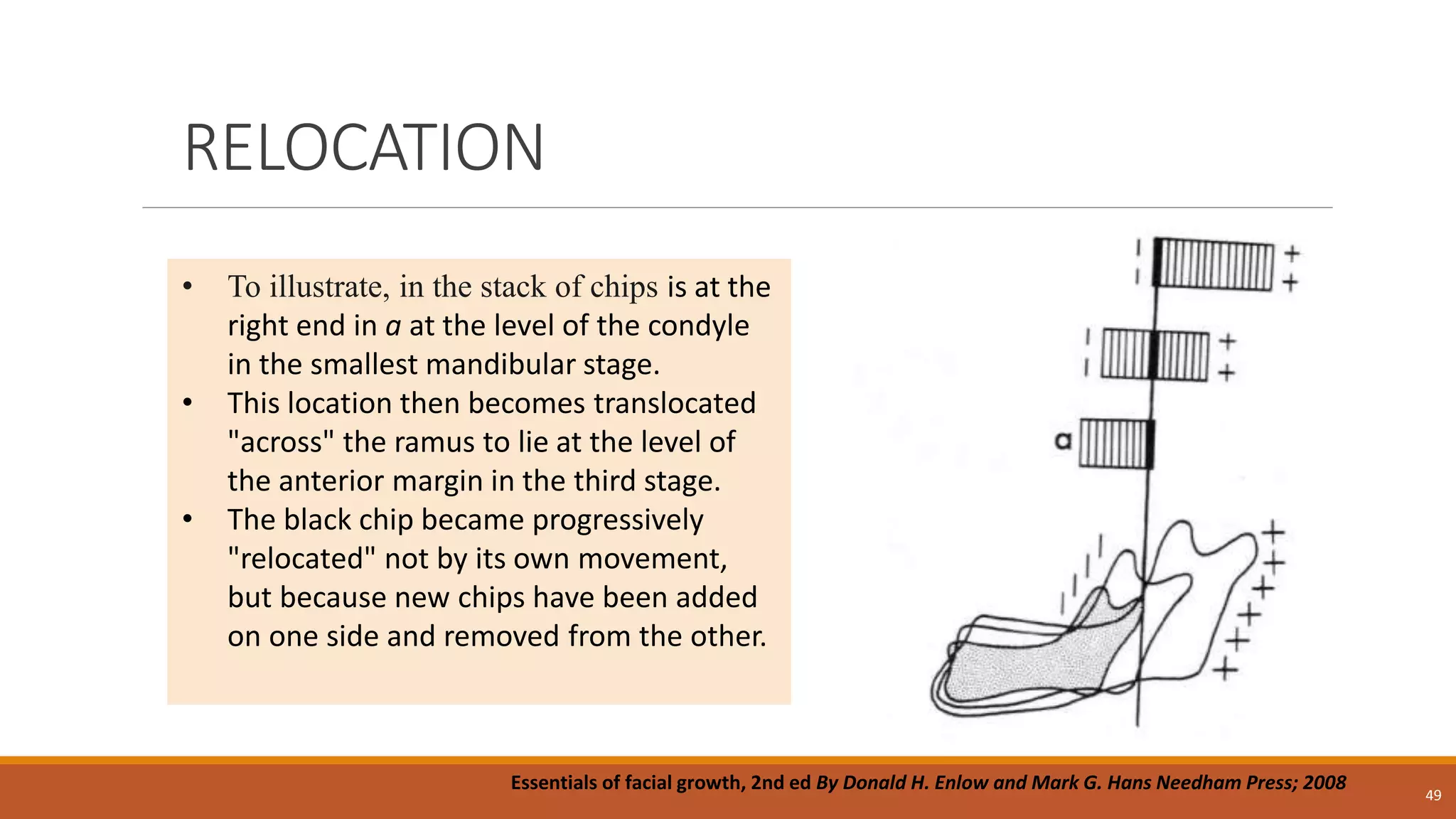

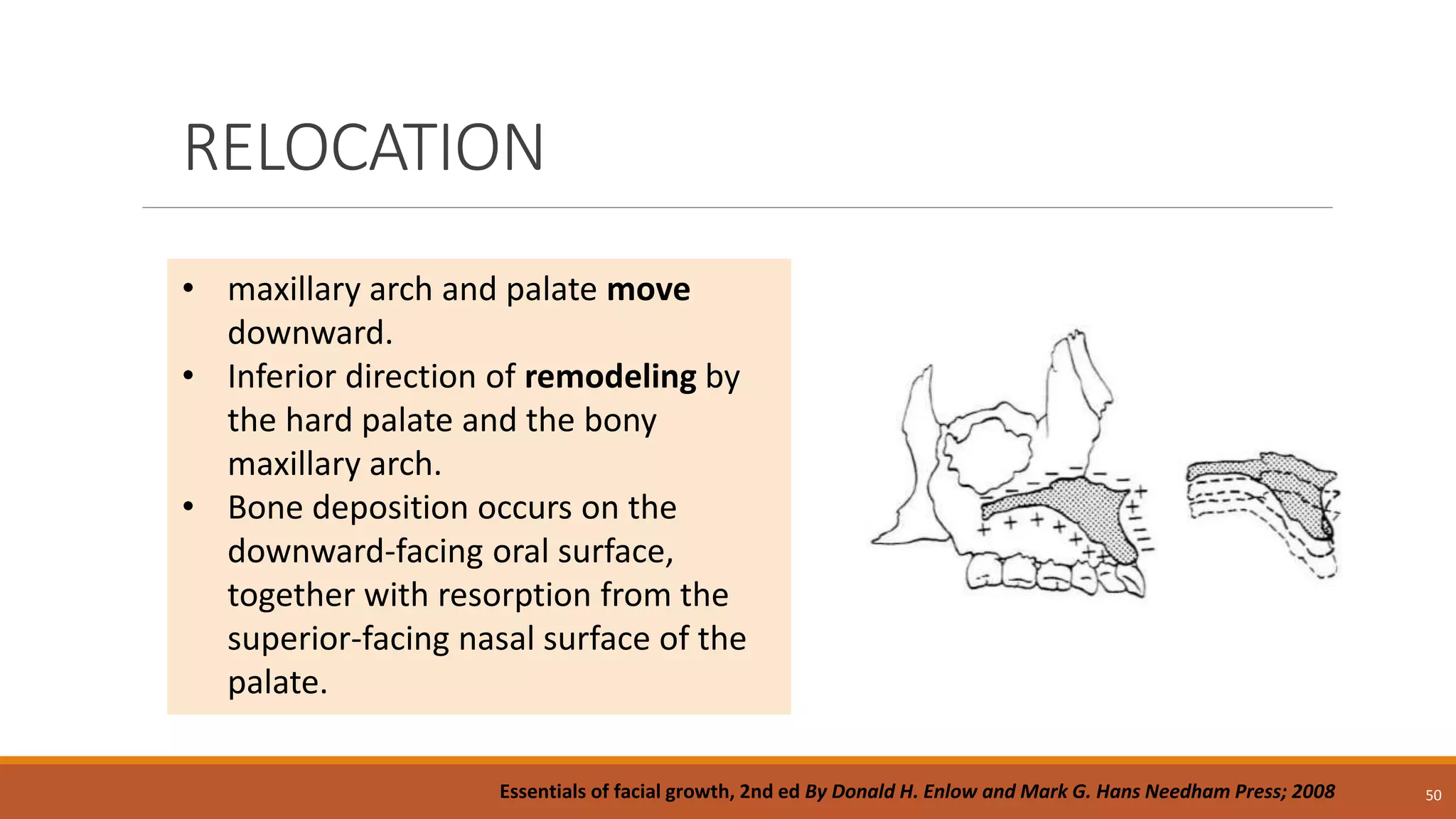

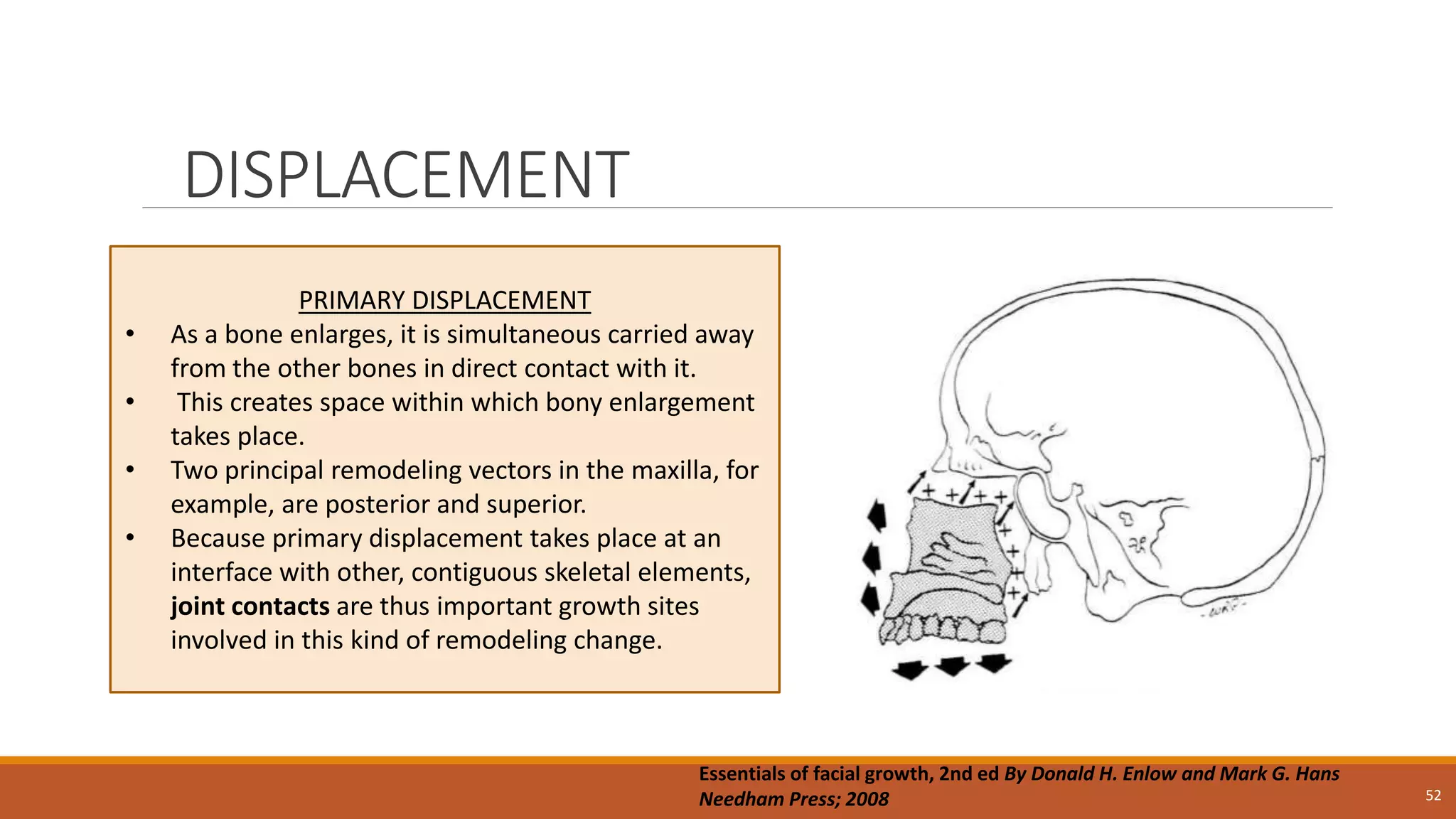

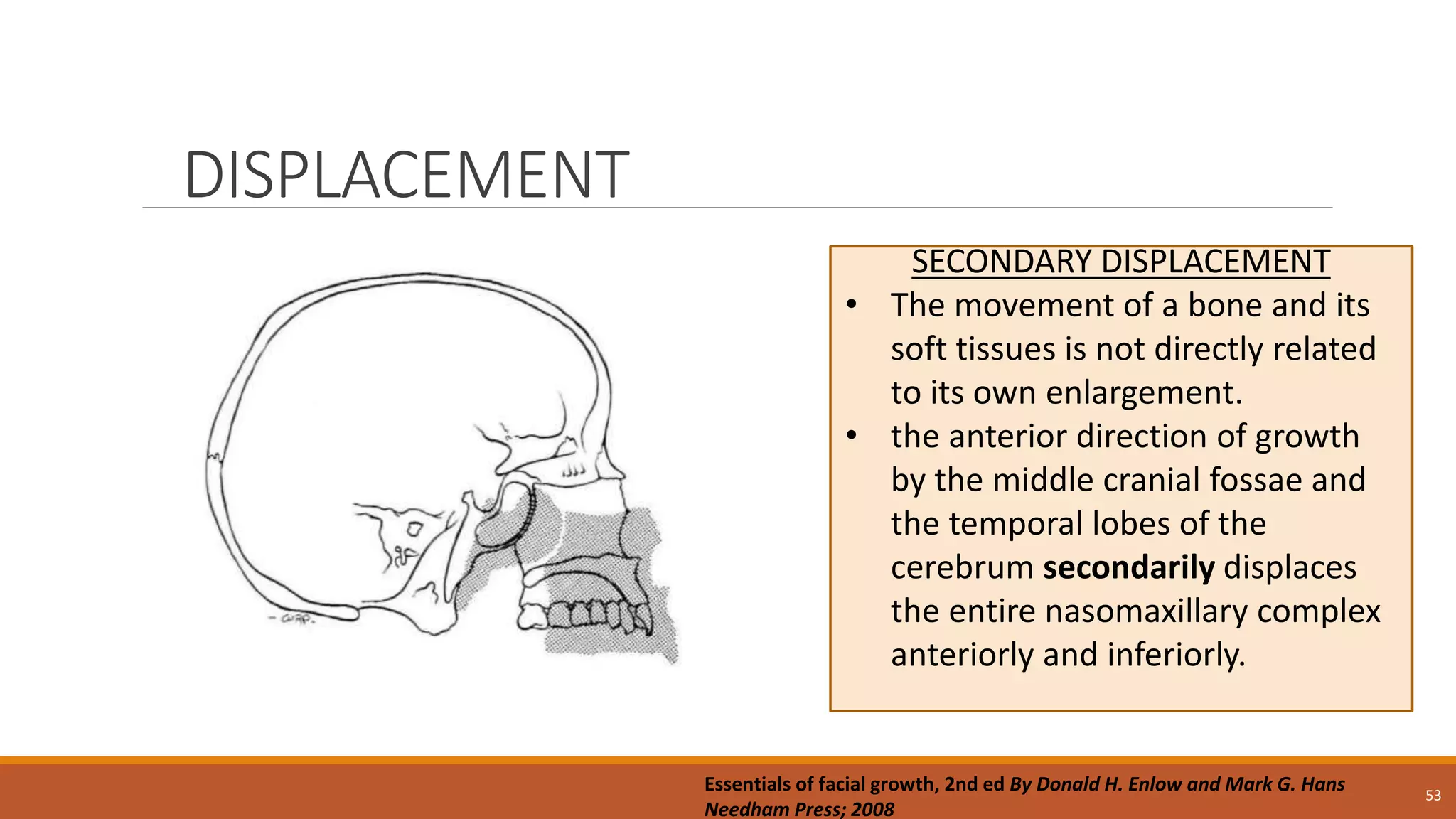

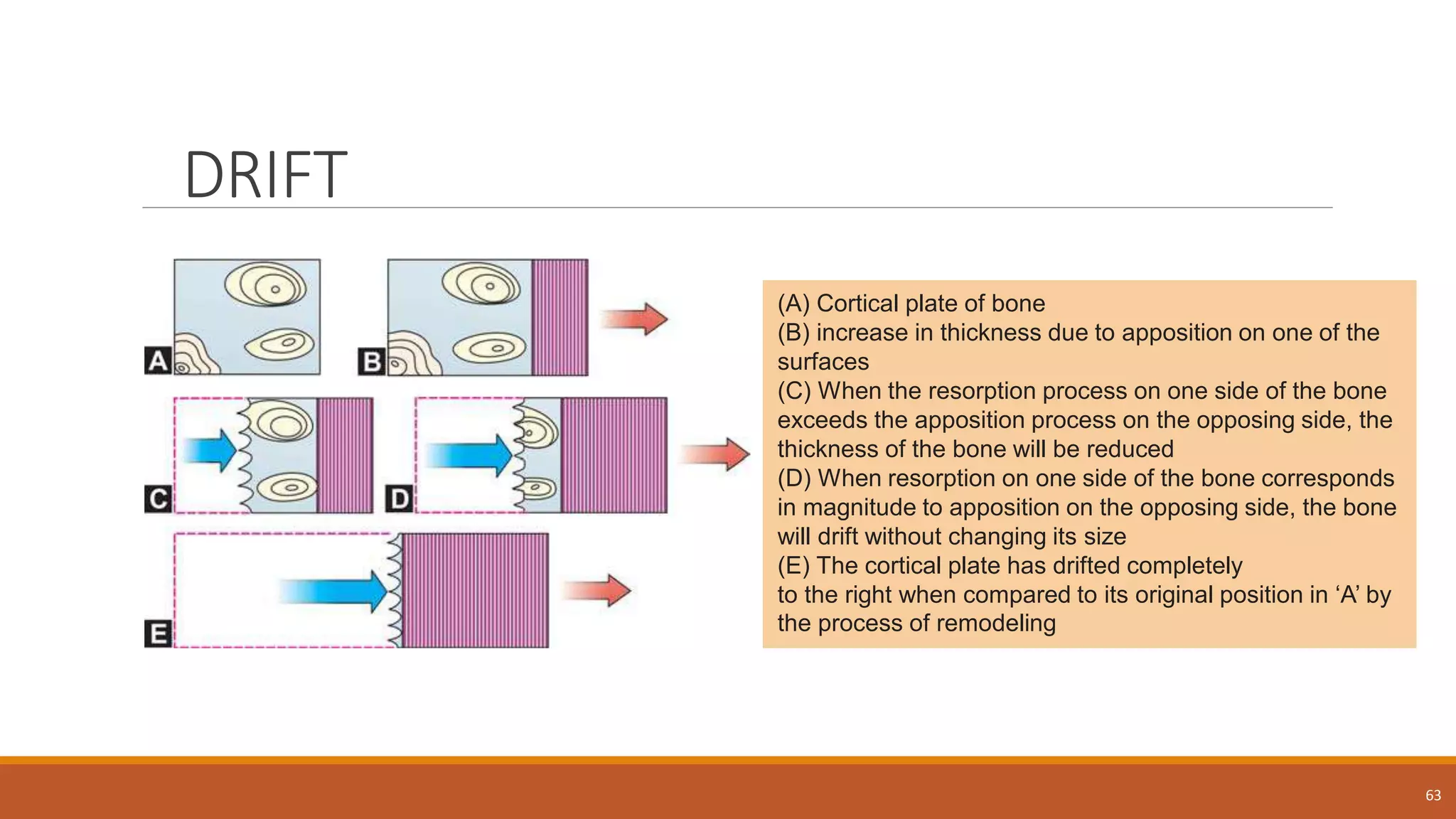

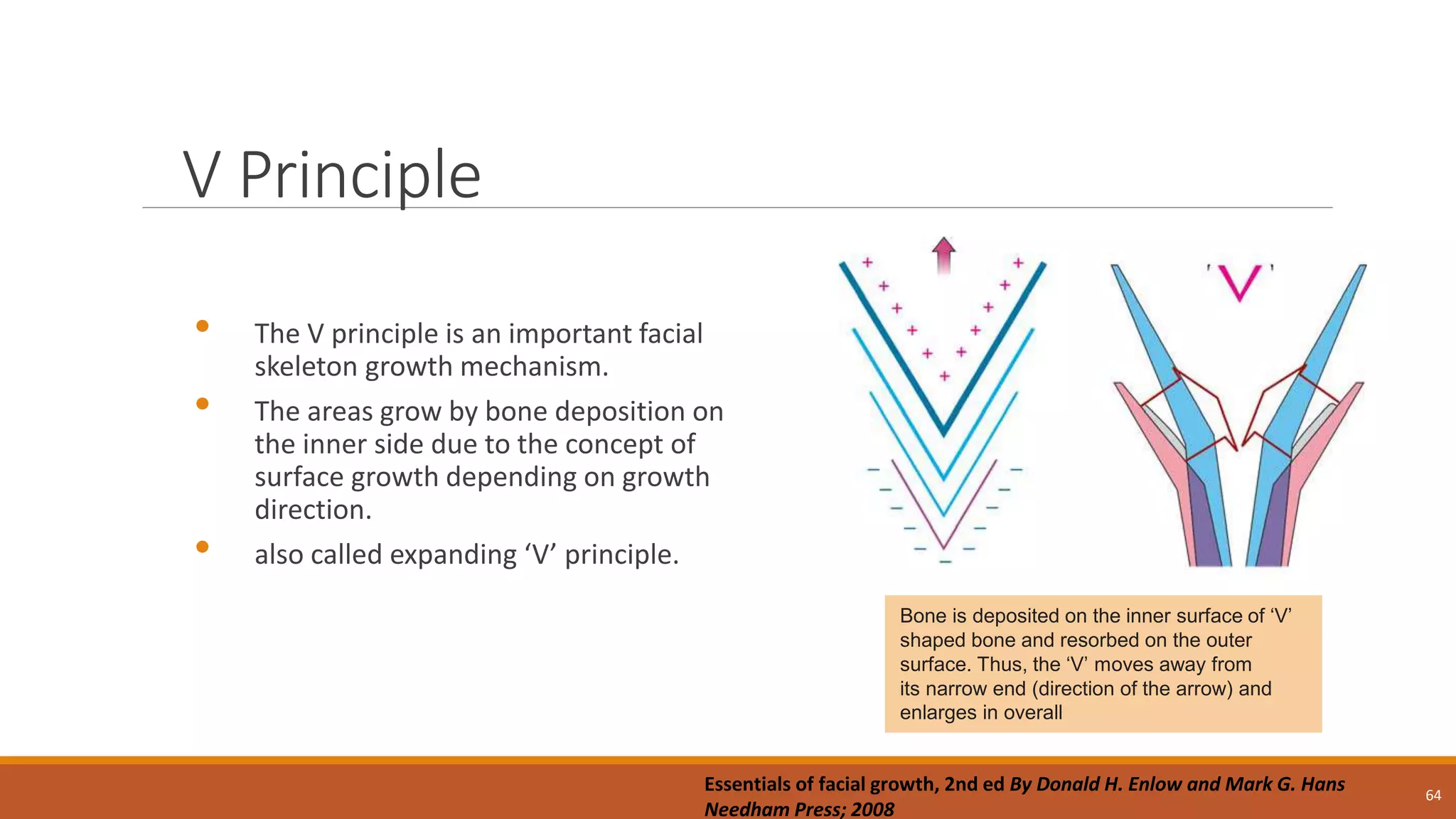

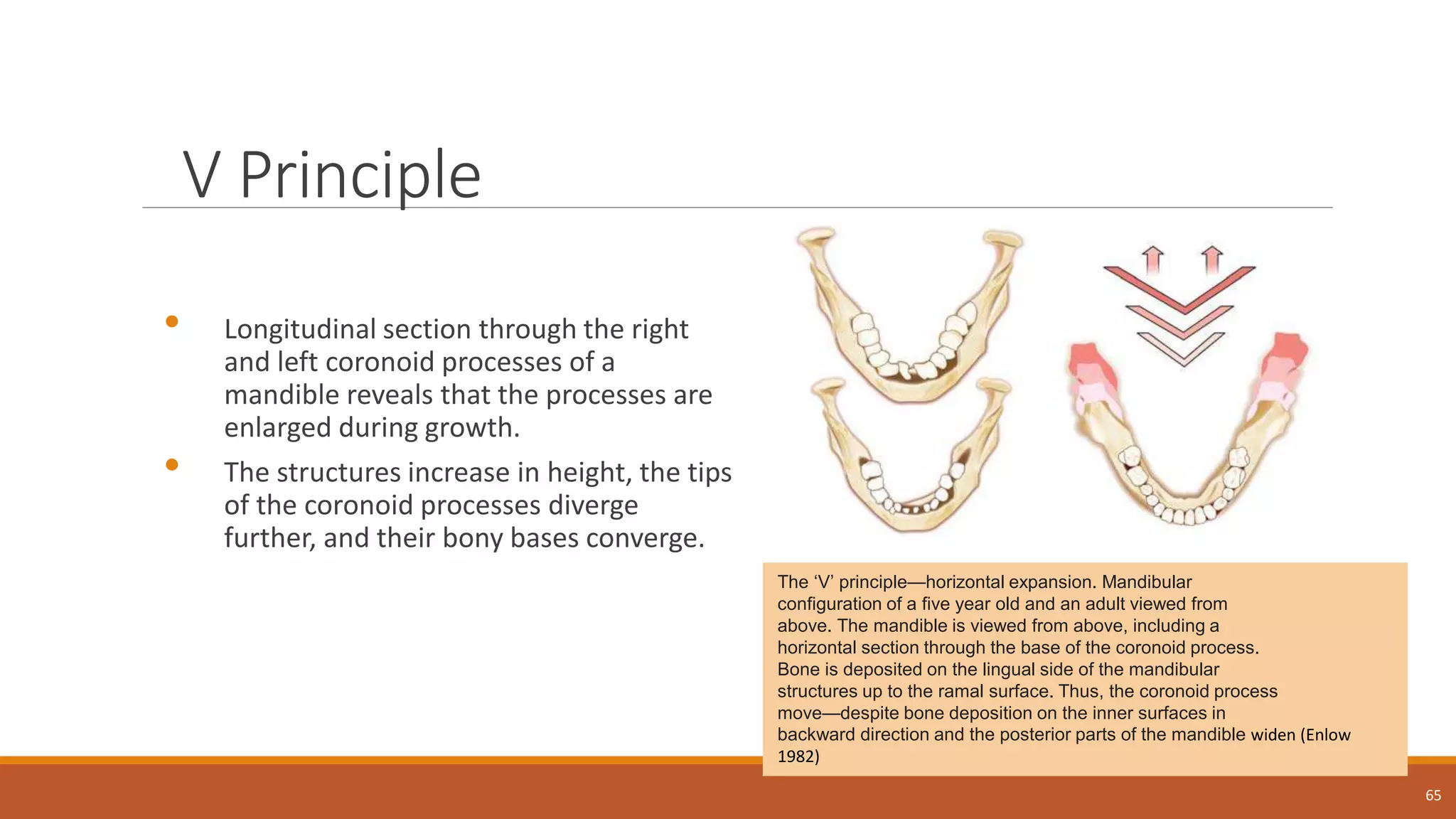

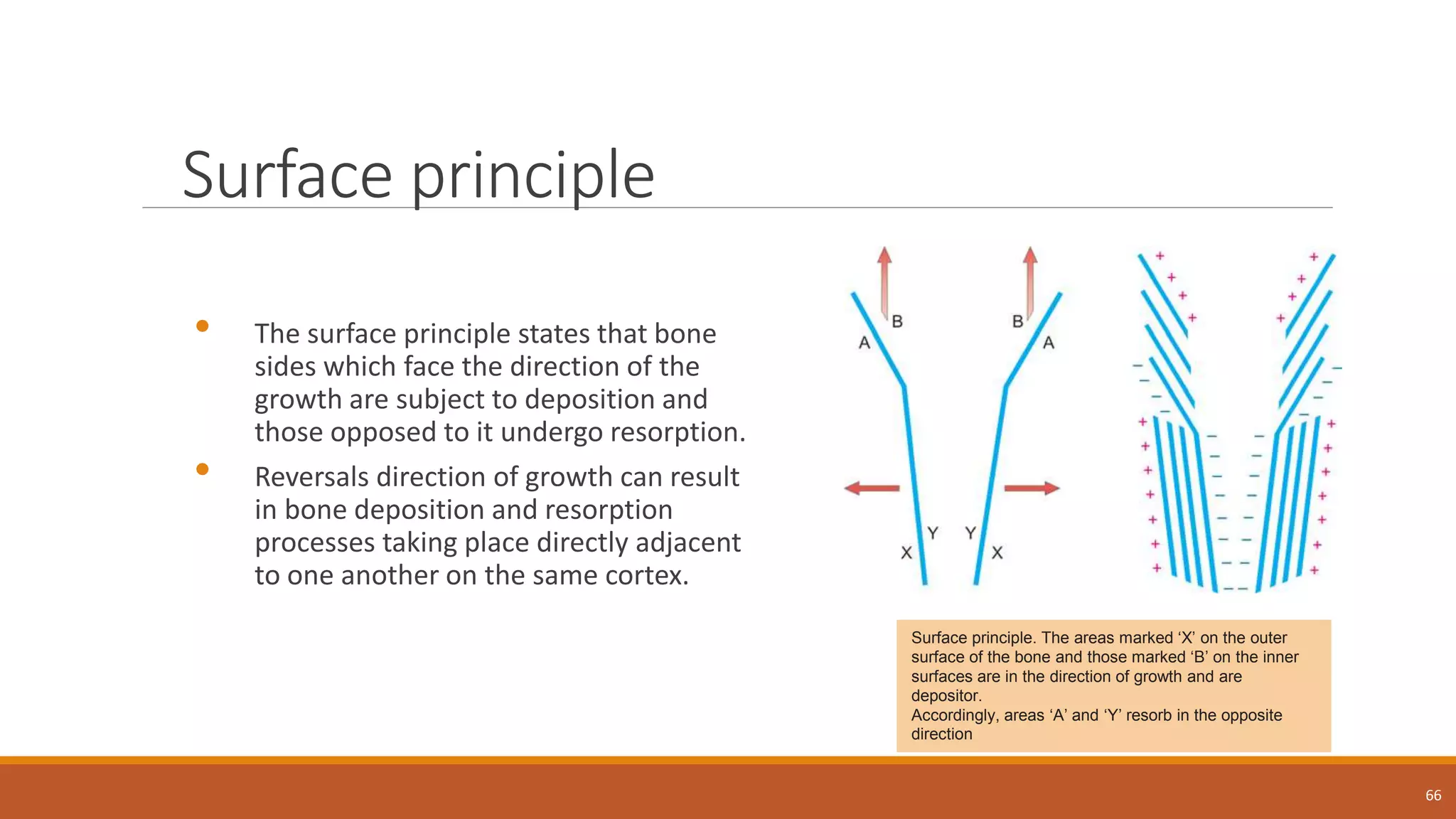

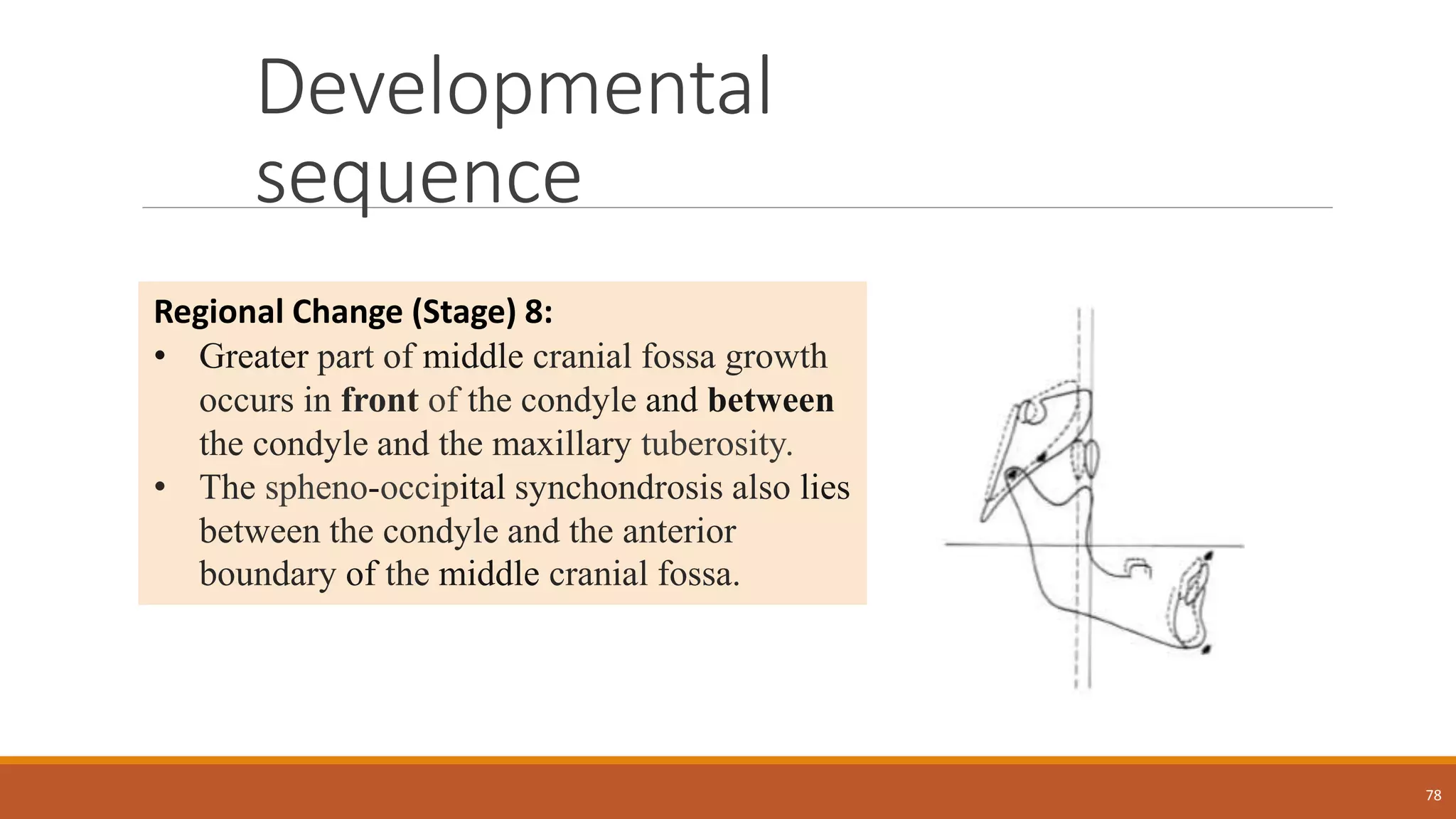

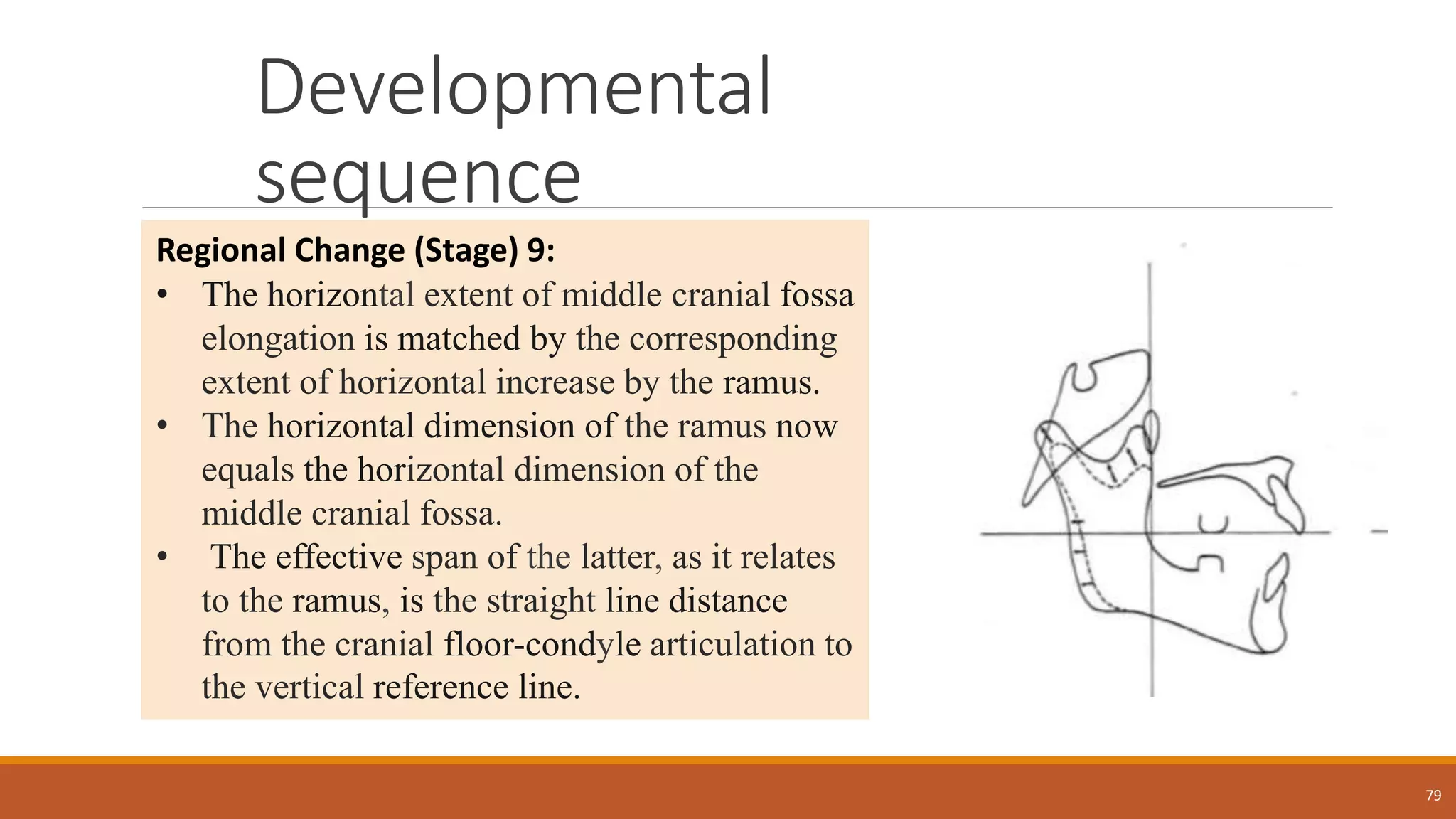

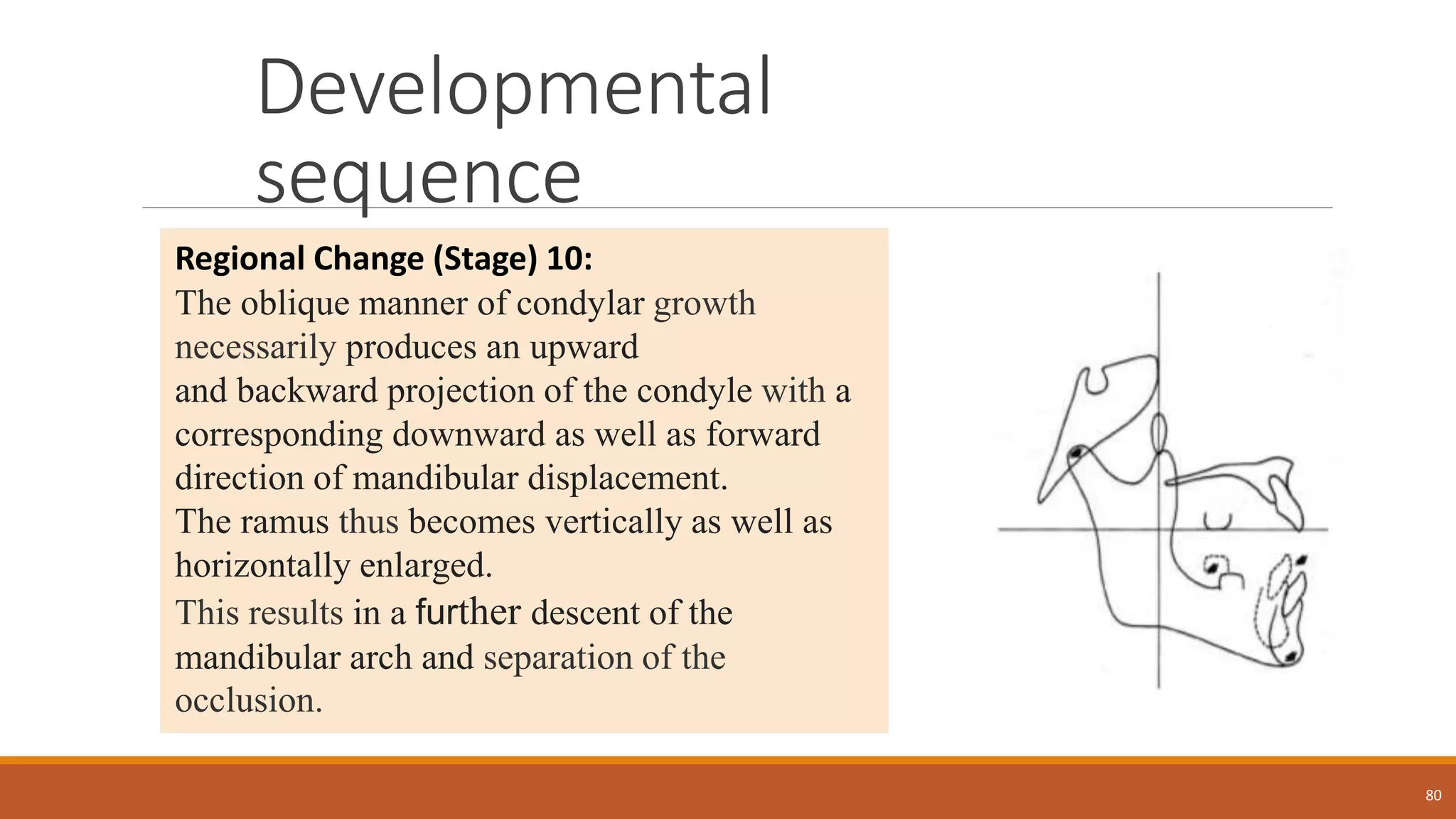

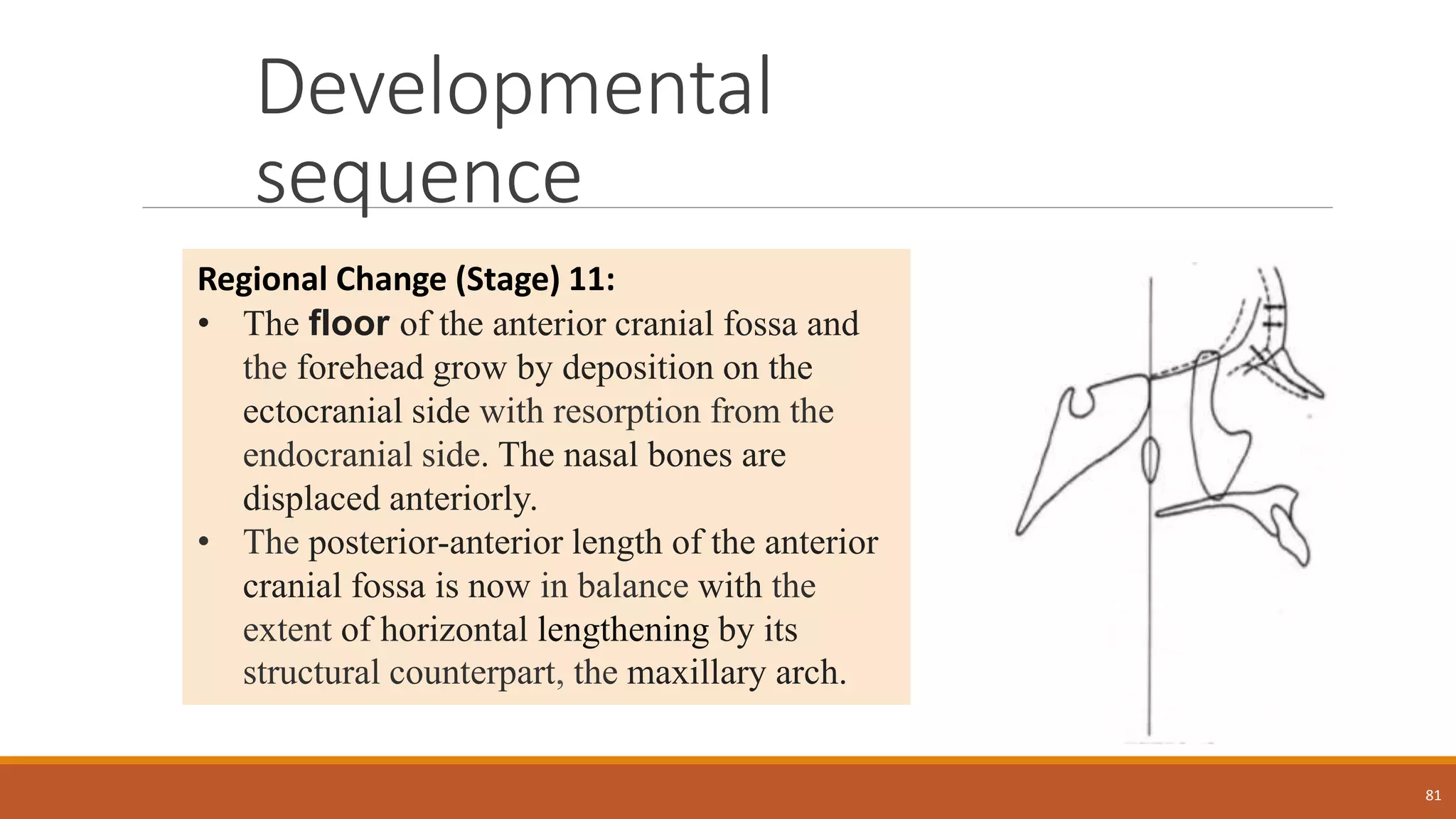

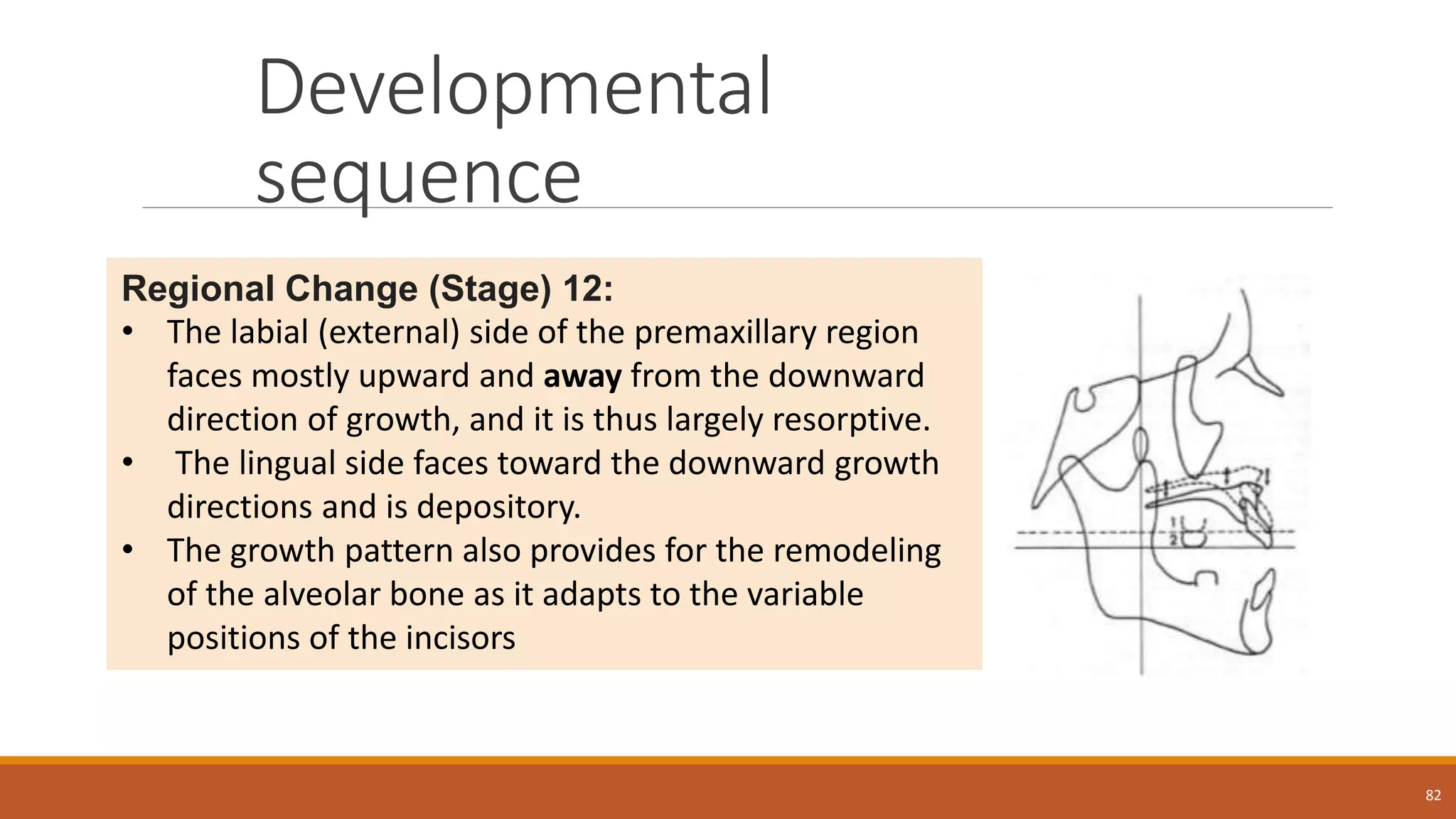

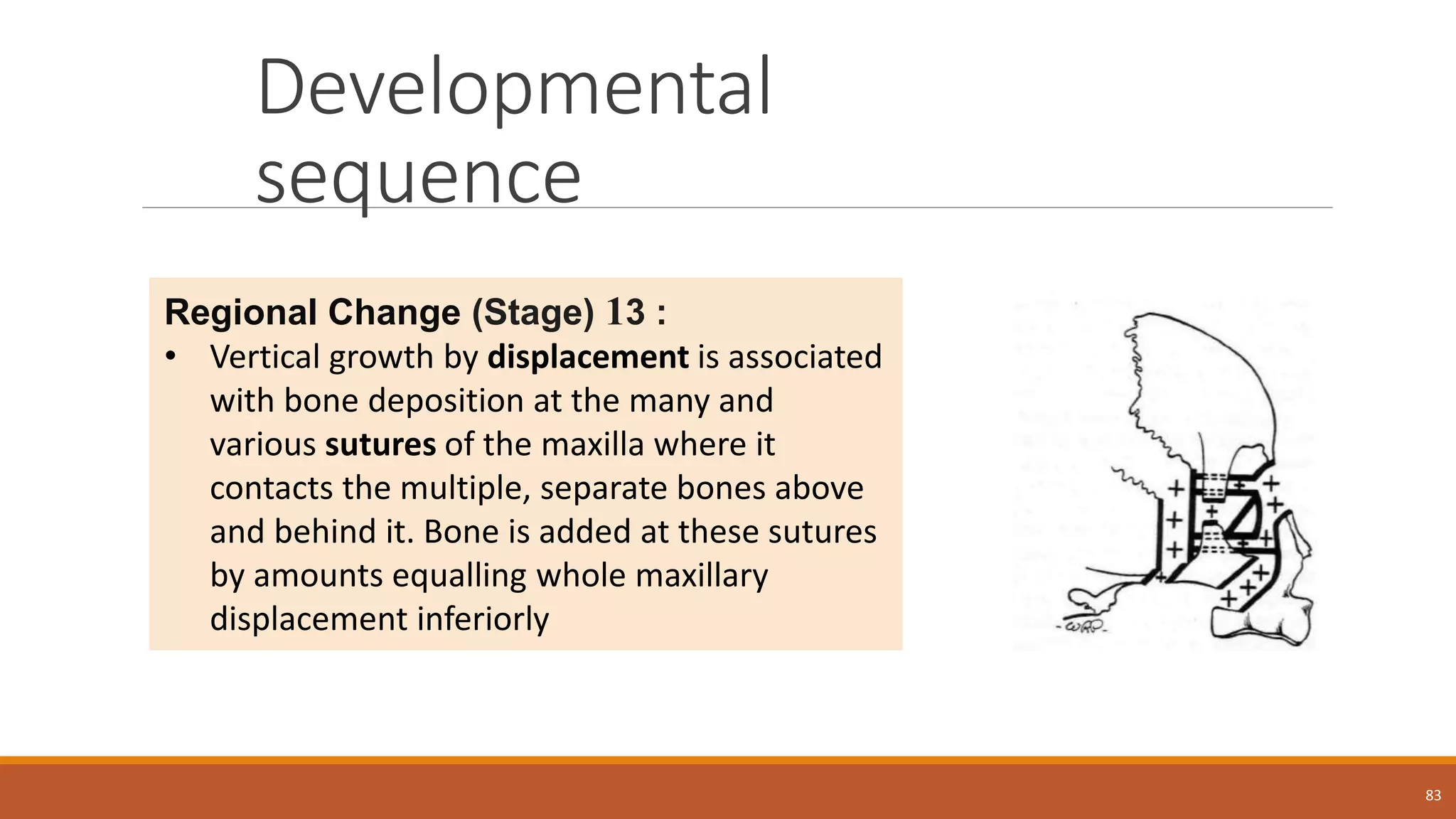

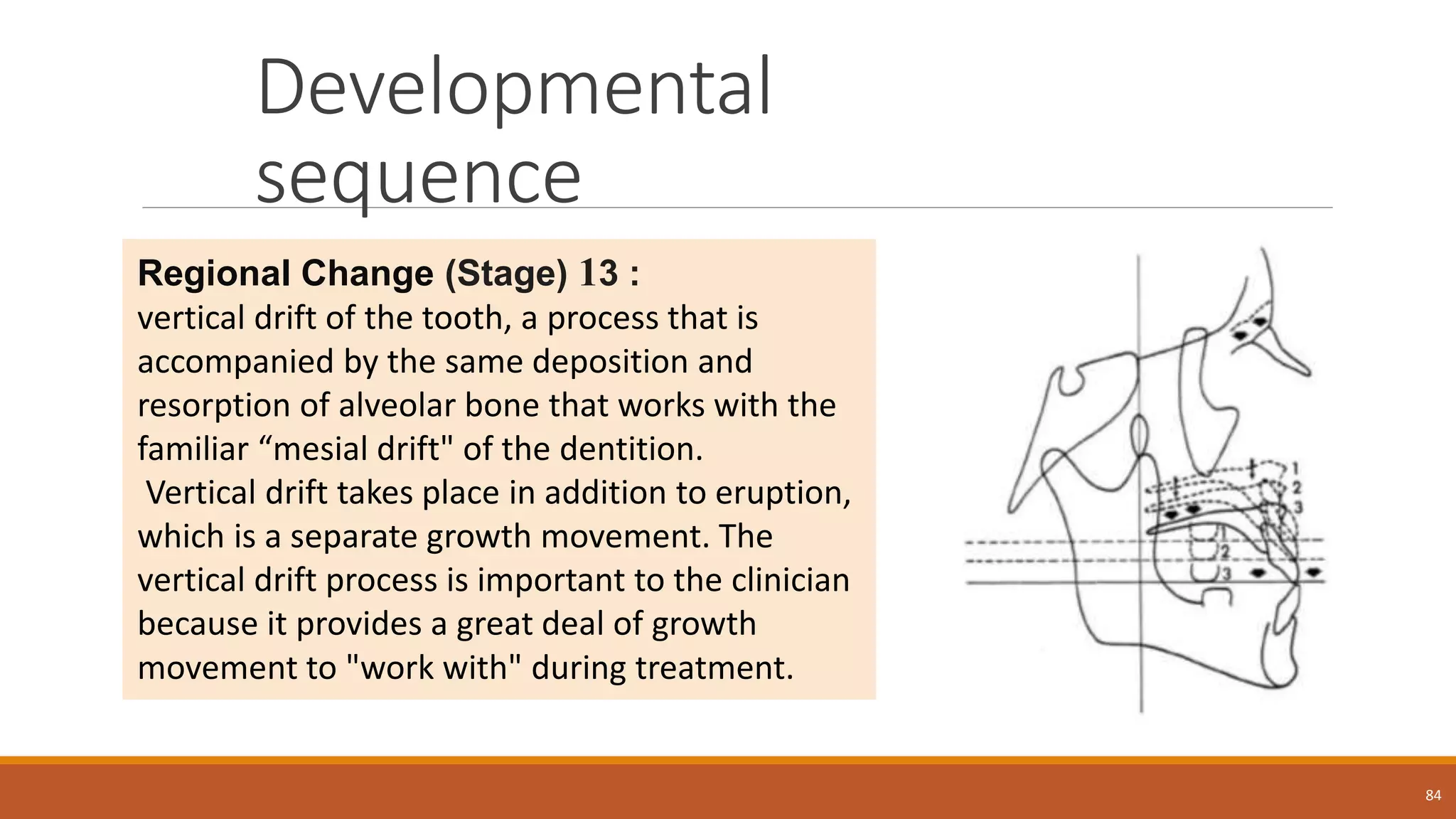

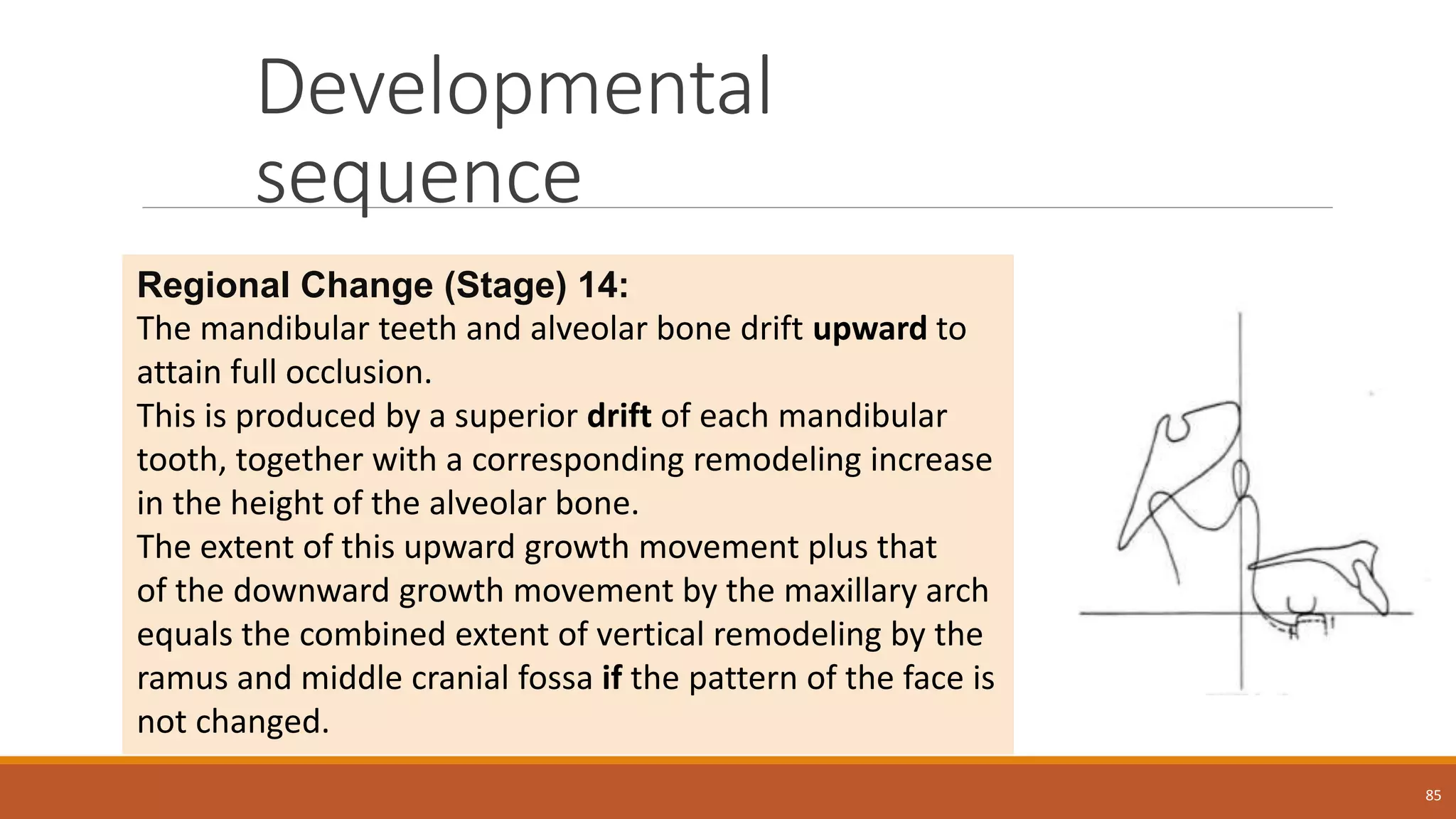

The document provides an in-depth analysis of growth and development, particularly focusing on bone growth through intramembranous and endochondral ossification. It discusses various mechanisms and patterns of bone growth, methods for studying growth, and the importance of understanding growth patterns through statistical approaches. Additionally, it highlights different biological processes involved in physical growth, such as chondral and sutural growth, as well as essential techniques like craniometry, anthropometry, and three-dimensional imaging.