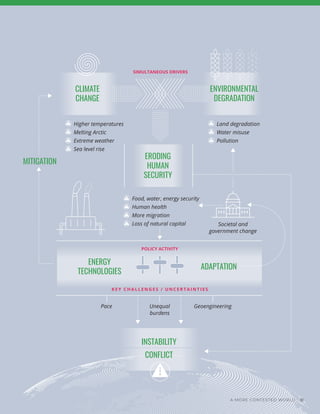

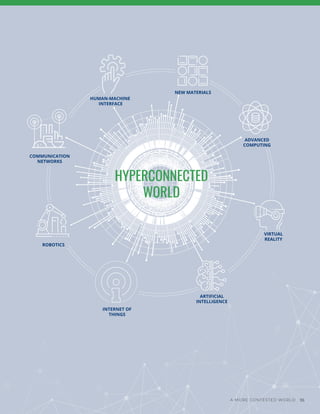

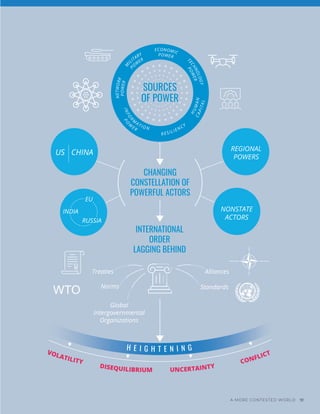

The structural forces of changing demographics, environmental challenges, economic shifts, and advancing technologies are interacting with human responses to shape emerging dynamics at the societal, state, and international levels. This is creating disequilibrium that is fueling greater contestation within communities, between states, and across the international system. How these dynamics unfold and interact over the next two decades will determine the trajectory of the global order in 2040, with scenarios ranging from a democratic renaissance to separate spheres of international influence. Adaptation to these forces of change will be imperative for all actors.